Slouching Towards Baghdad

There are many who use the word “Bush” like past centuries deployed the name of “Allah” (or “God” or…) as a way to stop thinking, as a shorthand for some higher function gone terribly wrong. How could Bush kill my son? How could Allah take away my home in a flood? Even in the smoke free, vegetarian swarms of left leaning politicos, the burning Bush appears as totem and mirage, disguising the crucial fact that the policy of American empire has remained unchanged for a century no matter who appears in the newspapers every day.

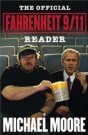

The American republic was formed in a deliberate act of genocide against the native Indians who called the land home long before Protestants took up arms against them. The original thirteen colonies began expanding as soon as the ink was dry on the constitution (a document written by white slave owners to protect their property), and managed to seize large tracts from the Spanish empire, finally venturing offshore to establish concentration camps in the Philippines and a Mafia paradise in Cuba (to say nothing of the Panama Canal, the secret and illegal bombing in Cambodia, the three invasions of Canada…) The latest venture in Iraq is no different, if there were no oil there would be war, and certainly no occupation (look how quickly they allowed Afghanistan to slip back into opium production, misogyny and warlord rule). So it made me uneasy, at first, when I saw “Bush” appear in Michael Moore’s new film so prominently, the Cannes-award-winning, 100 million dollar box office success story Fahrenheit 9/11. Sure the guy’s heart was in the right place, but why beat around the Bushes?

Despite his own millions, Moore remains a populist, and he tries to do for American foreign policy what he managed with such élan in Bowling for Columbine, to provide both a recounting of once current events, and their structural underpinnings. Why is America at war in Iraq? What does that have to do with the airplanes of 9/11? In a brisk montage he takes us through the Florida electoral fraud, the vacationing president, the ludicrous marriage of Iraq with 9/11 and the failure to find weapons of mass destruction. He also takes pains to elaborate the relations between two oil families, the Bushes and Bin Ladens, and shows Bush senior pimping for his Saudi counterparts, armed with daily CIA briefs. Moore’s pursuit of Bush wins him this insight: American foreign policy is an extension of class privilege. As Chomsky has stated time and again: poor people subsidize the rich.

While the film’s first hour is a model of incisive clips and commentary, the second hour is less clear. It’s one thing to point out that no weapons of mass destruction were found in Iraq, but Moore fails to point out that tactical nuclear weapons were used by the Americans in both Gulf wars (leading in the first to the “Gulf War syndrome” illness which has affected more than half the American troops), and he clearly has no idea of how to present the occupation. This would require at least a cursory understanding of Iraq. Instead he retreats to the recruiting stations of America, and specifically to his hometown in Flint, Michigan where the class war is being undertaken (again) under the disguise of patriotism. We go to the mall where teenagers without prospect (the economy has failed them, a victim of outsourcing and globalization) are being feted by recruiters. But would it be too much to point out that the worst of the occupation is being felt by the people in Iraq, and not the families who have lost soldiers there? To Bush’s glib reason for the existence of “terrorism” (“They hate our freedom”), Moore offers up the cost of defending it. But what about those who had to suffer under a dictator armed and supported by the United States, then had to suffer American-led sanctions which saw more than five hundred children die each month for lack of potable water, before going through an invasion, nightly raids and curfews, electricity black-outs, chronic water shortages, and massive unemployment? Yes, the profiteers are shown in Moore’s film in all their preening self-justification (Oh Haliburton! Oh Bechtel!), their multi-million Pentagon contracts firmly in hand, but what about the real cost of their plunders, the heaps of dead, the prison tortures and slaughter?

What Moore’s flick never manages to unwind is the solipsism of America. This is a country where other countries appear in the news only when they are being invaded. For all his shooting (or borrowing) of footage in Iraq, there are no Iraqis interviewed, none appear except as grieving mothers, their horror at lost sons and daughters another trophy moment for export. There is nowhere a reminder that the “Vietnam War” was called “The American War” by the other side. That the Other—Vietnamese, Cambodian, Nicaraguan—is as real as a New Yorker, as one of those New Yorkers who died in the Twin Towers for instance, this is something Moore is sadly unable to achieve. While his movie remains a challenge and defiance of many conventional wisdoms, the empire still lurks behind his editorial decisions. The Iraq war for Moore is finally about the sons and daughters of Flint, and not about those unnamed others, who remain the collateral damage of money and power.

Originally published in: Dok Revue, a newspaper published by Jihlava International Documentary Festival, 2004.