Penelope Buitenhuis: Guns, Girls and Guerillas (1990)

Penelope Buitenhis is a Canadian independent filmmaker who has been living and working in Berlin for the last decade. She has produced and directed fifteen short films in Canada, the US, and Germany and has a couple of features to her credit. Her new narrative works are set in the ghettos of urban centres — New York, Berlin, Toronto, Vancouver, and Rome — and are edited so that the West appears as a single, vast necropolis of decay, neglect, and ruin. As someone who consistently shows her work in a number of different countries, she understands the limitations of linguistic address. Her work relies, instead, on a symbolist ethos, training its lens on a variety of counterculture punks, drop-outs, and outsiders. These are angry tales from the outside, filled with “bad girl” attitudes and a romantic lean toward revolution. Inveighing against police violence, atomic weapons, and state control, Buitenhuis has knit together a series of dramatic encounters between stated and stateless, set in the ruins of history and the failed project of Western civilization. Working primarily in super-8, Buitenhuis posits a cinema of resistance and protest, lending voice to those left behind.

MH: Where did you learn about filmmaking?

PB: I tried to get into a school in Paris, but my residency papers didn’t come through at the last minute. As a contingency plan, I’d applied to Simon Fraser University because I heard it was one of the few schools that didn’t follow a commercial vein and they paid for your filmmaking. I never had any money, so if I was going to do it, I had to do it there. I never considered movies an art form, I just went for fun, like every other kid. When I was eighteen, I got this education about European film and realized there were other possibilities. I was outraged that I hadn’t even heard about this work. I think it’s still true, that unless you live in the privileged artistic world, you don’t hear anything about it. After the course, I went to Paris and got involved with some documentary filmmakers and caught the bug. I also realized that Paris wasn’t the place to be a female filmmaker. I wasn’t interested in being an actress, and they could never understand why I would want to learn anything technical. Editors and script girls are about the only roles open for women in Latin countries. It’s very much a man’s world. Canada’s the same, but Germany has women working in all facets of filmmaking.

MH: Tell me about They Shoot Pigs Don’t They?(15 min super-8 1989).

PB: I started making Pigs when I came down to San Francisco in 1987 to show political documentaries from Germany about the census. I don’t know if you heard about it here. It’s an obligatory census that everybody had to fill out about their income and personal statistics, and if you don’t comply there’s a five hundred mark fine. It posed questions about what the government should or shouldn’t know about your personal life. I wanted to demonstrate to America this enormous resistance because here we tend to give out information so willingly, without knowing how it’s going to be used. On the way from Germany to show these documentaries, they wouldn’t let me into the States. They were very suspicious about the tapes. In the end, they found me in the computer, and it turned out there was a warrant for my arrest for some car insurance thing five years before, which I didn’t know about. I was handcuffed at the airport and taken to the police station, and basically, that started my rage against police. That summer I’d been stopped by police a number of times and taken in for ridiculous reasons. Charges were always dropped, but…

MH: This was in Germany?

PB: In Vancouver. I felt there was a real tendency in Canada, more so than in Germany, towards a kind of vigilante police activity. If the guy didn’t like your face or the way you talked or if you said what you thought about things, then it was quite easy to have false charges laid against you. I’m a white middle-class person, so I can imagine for others it must be a lot worse. It was ironic because I was coming to San Francisco to show how the computer is used against the individual, and that’s just what happened to me. There’s quite a strong anarchist community in San Francisco, and I asked some people if they would like make this film with me. That’s where I started shooting. It was an ongoing process for the next three years, making bits in New York, Berlin, and Vancouver. I didn’t ever write a full script. I adapted it as I went along.

I wanted to show that certain portions of society never get media access, and that the only way to get it is to forcefully take it. The other thing about the film is that in Germany, particularly, there’s a nostalgia for revolutionary images: the Baader Meinhoff, Che Guevara, the fist, the black flag. All these things that are constantly re-used in demonstrations and leftist rhetoric. I feel those kind of symbols and “Down with Imperialism” rhetoric are no longer applicable today, and that a new form of resistance has to be developed. Constantly recalling this sort of nostalgic imagery of revolution makes it absurd. The main character in the film, Yvonne, the black woman, is surrounded by these posters, and she’s obviously a part of this imagery, affected by it. At the same time, she’s never lived a revolution in her generation, so in a way it’s a dream that’s never been fulfilled.

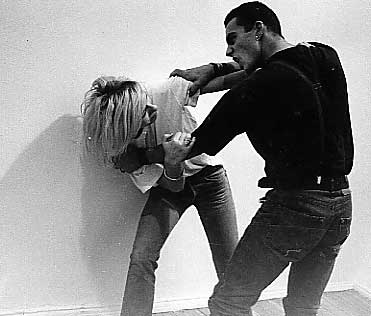

What triggers events in the film is the killing of this man Keane in Harlem by police who claimed afterwards he was a crack dealer. But neighbours said he’d never been involved with crack; he was an accountant. The cops said they found a vial of crack in his larynx, which everyone claimed they planted after he was killed in order to justify his shooting. In They Shoot Pigs, the Women Attack Pigs Revolution begins with a takeover of ABC-TV and begin a national broadcast that reads an anti-Pig manifesto. Police everywhere become the targets of this revolutionary coalition. Eventually some members get hurt, and the revolution is called off to avoid any more bloodshed. The remaining members hijack a plane to Germany to start again. In the end, the film fails because it’s not clear enough. In a way it becomes a slapstick comedy about revolution. They end up hitting police on the head with sticks, but what I’m really getting at is that these ideas of takeover are really not feasible anymore, they’re fantasy.

MH: Within the organization of the revolutionary group a very distinct hierarchy is set-up. There are a couple of people who talk, and the rest follow orders. Yet one of the things they’re fighting against is exactly this alienation of duties and responsibilities. They’re protesting a lack of media access which has become too centralized, which we can only passively accept into our living rooms, and yet this same kind of top/bottom split exists within the group itself.

PB: Anarchy’s idea of “all leading all” is nice, but this quickly becomes chaos, so, in a sense, I criticize the idea of anarchy as much as dictatorship. In the revolutionary groups of the past there were leaders. That’s the only way it could work. In non-urgent situations, collaboration and non-individualism can function, but in situations of direct action, I don’t think it can. Part of my mandate in making films is that, because I can’t pay anybody, I allow them creative input as compensation. The women reading the manifesto made a lot of changes to it. They decided on the choreography of the guys behind them, and the costumes they wore, for instance. I didn’t tell them to wear black bras; that’s how they showed up. I said, “You’re supposed to be tough leaders — interpret that how you will!” Some feminists feel uncomfortable with that representation, but that’s what those women chose to do. I did the same with the soundtrack: I gave the Rude Angels, a band from Berlin, free rein. I would go in every couple of days and listen to it, and if I really didn’t like it, I would talk to them, but basically I didn’t tell them what I wanted.

MH: Guns are a recurrent motif.

PB: For me it’s amazing that they could take guns away in America and drop the murder rate by half. Guns are such a cold way of killing, you don’t need any physical contact. In Europe, a lot of people are uncomfortable with my use of guns all the time, but I’m really uncomfortable with America’s use of guns. People I would never imagine have them in their homes. The gun is an admission that you’re prepared to kill.

MH: You show Keane murdered in the film.

PB: That’s the one element that actually happened, this guy was killed, and for that reason I made it quite graphic. It’s not a revolutionary dream; he died unjustly at the hands of the police. Not to forget.

MH: Most experimental film has very little to do with violence.

PB: Is it a collective denial? Perhaps there’s enough violence in other forms of representation that we can leave it out of ours. Pigs takes place in New York, which is a very violent city, and the cops are everywhere showing their cocks, their guns. It’s there in the papers everyday. But Pigs is also a criticism of revolutionary forms, because violence creates violence. Any revolution that tries to undermine a system often ends up using the apparatus they’re fighting, and I’m against that. Unfortunately, though, to fight you often have to use the same method of destruction.

MH: It’s a real quandary for makers — whether to use a form people can understand, like narrative for instance, and then have it appropriated by the mainstream. On the other hand, you can find a different kind of form, which quickly leaves most in the dark. How does your work function — who would see a film like this?

PB: Generally I’m a kind of packrat filmmaker. I just take my films around, as I’m doing now, to the Euclid or the MOMA or the American Institute of Film in Washington. I move them myself, since my experience for short films and no-budget films has been that there isn’t a lot of incentive for distribution companies to push them. There’s no money in it.

MH: But do you see the films working as a form of direct action? How do they function politically?

PB: The reaction in Europe has always been very interesting because, although I live in Germany, much of my work is based in America and American culture. Even people in alternative cultures have a certain image of America which I think is incorrect. They assume a very glossy, complete picture, so people are often surprised at the decaying ghettos in my work. But most insight comes out of discussion rather than in direct response to the work, because when I show my films six at a time it’s a real overload of information and images. People are overwhelmed. Response comes when we start talking.

MH: Tell me about Disposable (14 min super-8 1984-86).

PB: It’s about disposable North American culture, an ironic idea for Europeans because they’re surrounded with tradition and history. They don’t even realize how much tradition plays a part in their understanding, and those that do suggest it’s an impediment to your freedom of thinking, a weight they’re forced to carry. Disposable is set in an America which has turned its brief history into a throw-away culture of television and magazines which fosters a cultural amnesia. That leaves museums and institutions as the places of our public memory, and I feel uncomfortable with their agendas. If you’re in Paris or Berlin, the shape of your space, the architecture, the statues and monuments, are a constant reminder of what went on before. In North America it’s difficult to remember anything.

MH: From a European perspective, “North America” was founded on removing our indigenous people. Our foundation is already one of erasure and genocide. Disposable takes up this question of the custodians of memory. You show two men, one arguing for the importance of the past, the other lost in the present.

PB: Both have validity. Europeans envy America because an intuitive response to image making still seems possible. But I don’t think we’re children; it’s not possible to be naive or to go back, any more than it is for the Europeans.

MH: Your filmwork is also straining the traditions of a certain kind of experimental film work.

PB: Even though I really enjoy working in an experimental vein, when I took my films around to places that didn’t necessarily have educated film audiences, I would lose them when it became too obscure or experimental. I want to form another kind of narrative, a new narrative that’s not linear in its juxtaposition of sound and image, and tries to disturb the typical formulas of narrative film. I want to make it entertaining for people to watch. I don’t want to lose them. I’m very much against this tendency in North America, with its endless superimpositions and text, where I lose what’s going on; it becomes intellectual masturbation. Maybe it works for other filmmakers, but my purpose is not to preach to the converted. I’ve shown just about everywhere, in warehouses, cafés, and out-of-doors, really trying to reach other kinds of audiences. A lot of people’s response is, “Oh, we’ve never seen stuff like that, this is really strange, I never knew work like this existed,” and that’s what I want to get at. I want people to realize there are other ways of telling stories or talking about issues or presenting opinions, but I think it’s necessary to maintain a certain narrative line. So, in the last six years, I’ve turned much more towards narrative.

MH: What about the people who say that your work casts off the tradition of fringe film entirely, that there’s nothing left of it any more, it’s not experimental, it’s something else?

PB: “Experimental” means in any form or way in which you wish to make it. Experimental lies outside mainstream form and beyond that, I’d say it’s free rein. At the Experimental Film Congress in Toronto (1989) there seemed to be an accepted definition of what constitutes experimental film, which I found shocking. How could there be? How could it continue being “experimental” if it could be pinned down with words? Curiosity about the forms of communication has dwindled because it’s not so new any more, and a lot of people are fed up with obscurity. At the Experimental Film Congress I really sat back and wondered, “What were they saying in that film?” I didn’t understand some of the work, and I’m an educated film goer, so I can imagine for the uninitiated it must have been totally confusing. I’m not suggesting you need to dictate what you’re saying, but why do you make images? You want to bring something across to people. You don’t want to leave them totally confused when they leave. I think new narrative is a way we have to go now to be able to reach an audience that is fed up with experimental obscurity or endless superimpositions or layering text. I’m trying to make experimental film fun to watch, and I don’t think that’s such a bad thing!

MH: Purely formal film experiments seem increasingly to emerge from a certain kind of privilege, a class privilege, that has the time to worry about things like “film as film.” As well the increasingly academic and institutionalized context for work is heading production off in a certain direction.

PB: I agree. I’m continually surprised at the similarity of films in Canadian festivals. At the Insight Festival in Edmonton, all the documentaries took a form that was in the tradition of the National Film Board; the experimental work took a very obscure academic form, and when I showed my work, people were really shocked because it didn’t fit. Although people think of German film as being innovative, they don’t have nearly the history of experimental film that we do in America. It’s not institutionalized like it is here. Generally film schools teach you how to make film, rather than film theory, and as a result they’re not so patient with experimental forms.

MH: One thing that’s different between your work and other German fringe films is that many makers have a strong aversion to language. Long stretches of work will have no dialogue or titles, whereas North Americans seem obsessed with text. Your work is relatively wordy when compared with other German work.

PB: As an English-speaking person in Germany, I have a different relation to language, even though I speak German. Many sounds provide a non-verbal dialogue. I think sound is an international form of communication — it triggers thoughts and associations. But particularly in Germany, where language has been abused by Hitler and other orators, filmmakers are wary of their own language. Words don’t seem the same now. English can be brief and succinct in a way that isn’t possible in German; it doesn’t have the same freedom of juxtaposition. In English, you can put words next to one another in a stream of consciousness which is understandable because the words have an integral meaning in themselves. But in German, each word is very dependent on the words surrounding it. So you can’t free it from its history. Because I’m not German I look at the way they’ve put their language together — like the word “geschlectsverker” which means copulation, and in it is the word “schlecht,” which means bad, and “verker,” which is traffic. I used to think it meant “bad traffic.” But they can’t see that the word holds its own moral. When you’re in your own language you don’t realize the way language has been impregnated by culture, the way your mouth shapes understanding. Or “Leidenschaft,” which means passion, and “leid” is pain. The Germans never notice, of course, just as we don’t. In the same way, experimental film is concerned with the form, of how you do something, and when you make the form strange you’re able to see it, until the form becomes too strange and you can’t see it at all.

MH: Tell me about Indifference (20 min super-8 1988).

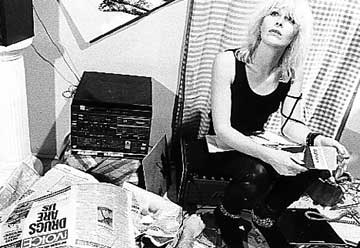

PB: That was shot in New York and Toronto with Samantha Hermenes. She’s so talented but never uses it, so I invited her to New York to make a film. We wrote the script in a day and shot it in two. We wanted to show that city living requires an indifference to the horrors you see around you. I still get tears in my eyes when I see the bag ladies in New York. But to survive you have to build up a certain disregard in order to remain optimistic and creative. So this woman sees a lot of ugly things which she ignores; they’re an everyday occurrence. She passes a murder, a dope deal, arguments, and corpses. She’s even blasé about her personal life — her apartment is trashed, she gets kicked out — but nothing really gets inside. Then it turns out that these events have been planned by a guy who is trying to inflict his paranoia on her. He’s bothered by the fact that she can live without being affected. All the things that have happened to her have been set up for her to see.

MH: Scripted.

PB: Yeah, it’s very much to do with constructing a film. The paranoid guy is like the filmmaker who’s saying all these events were no accident. She says she’ll stay indifferent and survive. Some say that’s a call for apathy, but I don’t think so.

MH: The paranoid suggests to her that all of these circumstantial events — the murder, the dope deal, the person lying dead by the sidewalk — are coming from one place. They make up a narrative in which she’s implicated. This is related to her in the form of a letter which she opens at the end, detailing the events of her day, showing their origin in the word. This letter has the form of a script, and this person then becomes analogous to a filmmaker.

PB: Most filmmakers are paranoid about understanding. That’s why they make dramas.

MH: Two things in her apartment seem to offer her some degree of comfort: her parrot and her mirror. I think there’s a distinct narcissism at work; she’s able to escape from her surroundings in the image of herself.

PB: She’s an extreme case. After she’s cut off the world, all she has left is herself. The mirror falls because of the violent argument next door, and this splintering of the mirror shows the outside world really stepping into her life, breaking her image. That’s when she gets the angriest.

MH: There’s a suggestion that there is no inside, that it’s impossible to be alone.

PB: That’s why it all continues even when she gets home. The neighbours are fighting, the landlord boots her out, the paranoid telephones. In the film, I use a heavy soundtrack by Mechanik Kommando because in New York you never escape the noise. I couldn’t live there because of the overwhelming sound. You’re never out of New York when you’re there. All my films are shot in ghettos, decaying parts of the world. It’s not random where I shoot or who’s in them. Fighting the Hollywood image thing is impossible, but despite their image overdose, people come out of my work with some sense of the unjust, fragmentary, dirty, decaying world. A lot of that has to do with the soundtracks. For far too long, sound has been secondary to image, but I try to bring it forward, to make them equal.

MH: Which film is shot off the television set?

PB: Combat Not Conform (4 min super-8 1987). It’s basically a summary of activities and demonstrations. Now it’s irrelevant because Reagan is in it. The demonstrations were against nuclear plants, which were only good for money in the end. Inside of all this a few people are trying to fight for something fundamental: no nuclear weapons in our country. I wanted to make an image of this resistance, to show it’s still possible.

MH: You made a film about the Berlin Wall coming down.

PB: It’s called Llaw (9 min super-8 1990) which is wall spelt backwards. It’s a personal diary about the days leading up to, and succeeding, the crumbling of the Berlin Wall. I was in the woods of British Columbia this summer, writing a script, and I kept seeing via satellite all these reports about the mass exodus from East Germany. Everyone said to me, “You should be back in Germany, it’s really exciting,” but I wondered what difference it would make. It was deeply ironic sitting ten hours from any city and still seeing images of what was happening at home, or what I call home. I returned to Berlin on the third of November, and showed this in the film via pixillation.

On November 4, there was a demonstration of 1.5 million people in Berlin Alexanderplatz, which was broadcast on East German television, and they were saying extremely subversive things, that the government should step down, they’d had forty years of oppression and now it was over. Writers, intellectuals, and poets spoke to the crowd. I watched it with a number of people who’d escaped from East Germany, and they were stunned at what was being said on television to the whole country. We knew then that there was no turning back, that it was just a matter of time. That broadcast said it all.

On November 9, the wall came down — I was on my way to a concert of Faith in the War. I heard the news on the subway at 7:00 p.m. and everyone started shouting. My equipment was locked in my apartment, which had been confiscated. I was having personal problems, so I didn’t get my camera until November 11, so visually I shot off the TV and shot a lot afterwards. November 10 begins a metaphorical dialogue between East and West. It’s set in the hallways of Brittania House, and revolves around the idea that we’ve been enemies for forty years, but all of a sudden we’ve decided none of that was necessary anymore. We see the camera move into a room where a couple beat up on each other and kiss in the end. This is intercut with images of 1961, when the wall went up and images of today, when guards are standing atop the wall and people are handing them flowers. That’s the power structure metaphor.

The next day is November 11, photographed in the next hallway. It’s about East Germans getting 100 marks when they come over, the whole money game. Inside the room, a business man opens up a suitcase filled with money and tries to give it to the same woman as before, now dressed as a typical communist. [laughs] She’s reading a book and tries to ignore the money, but eventually she takes it and stuffs it in her pocket and eats bananas. Bananas became a symbol of capitalism and exoticism because they didn’t have bananas in East Berlin, so when they saw this fruit in West Berlin…

MH: They went bananas.

PB: Exactly. The third scene had to do with the marketing of the wall, the selling of freedom and democracy. An American consortium offered fifty million dollars to buy the wall, but I don’t think they’re going to get it now; both British and French Museums have stakes. The whole world wants a piece of history. There’s not going to be much left at the end of it, everybody’s chipped away so much of it. I call it the pet rock of history. The last section shows a woman lying in front of her TV. An American survey taken after every major broadcaster was talking live from the Brandenburg Gates, showed that after five minutes most Americans switched the channel, so history brought the ratings down. [laughs] The film’s about the media spectacle, cashing in on the change of borders. The last statement goes: “History makes me suspicious; who will be the next enemy?” It’s about the artificiality of politics.

MH: When the news reports started coming in about the wall, I imagined all the filmmakers I spoke with in Berlin beginning to make work about it. The wall would create a whole new genre of filmmaking. No sooner did I get back than you arrived with Llaw.

PB: Everyone was there with a camera, looking at everyone else who was there with a camera. A lot of people were chipping away at the wall, which is a crime because the wall belongs to the East. At the beginning they tried to arrest a few people, but in the end they gave up because everybody was doing it. It’s not that easy to get a piece because cement doesn’t chip that well, and the only people who made a profit are the ones who came with jackhammers. West Berlin became horribly crowded, the subway was impossible, the shops were filled, the smog was unbelievable because the East German cars have no emission controls, and everything was sold out. So, all of a sudden, your normal everyday life was like New Delhi. A lot of West Berliners were fed up with the whole thing just in practical terms. I left on December 23 and it still hadn’t gone back to normal. Friends of mine were disturbed because they’d spoken up in the past and had to go to prison or leave as a result, but when a mass movement begins, everyone sings along. My friends from the East are looking at all these rightwing assholes who never said anything before and wondering what’s up. The reforms are good, but does that mean Eastern Europe will become another capitalist stronghold, another market? There’s a striking juxtaposition between the events in Eastern Europe and the American invasion of Panama — is this the freedom everyone’s moving towards?

MH: The real question is — what kind of shape will an oppositional force assume? How is it possible?

PB: There was a crazy euphoria that’s still going on in a way. When I go back I’m going to show my work in East Berlin and take my bike into the countryside. But the artistic world is frightened, because Berlin’s peculiarity came in part from being surrounded by a wall; it had something special. The strangeness of its circumstance brought many international artists to Berlin. That’s over now. Everyone’s wondering how the culture of Berlin will survive.

MH: How did you find your way to Berlin?

PB: In 1984 I made a film about squatting in London, Amsterdam, and Berlin, Alternative Squatting (15 min super- 8 1984). I was fascinated, and it was really cheap, and where I was living at the time, in Paris, it was very expensive and there was little alternative culture. So I moved to Berlin. There aren’t many places that have a strong alternative movement with an audience and press. Berlin is fantastic. Super-8 in Berlin is respected; I get a whole page in the newspaper about my work. People are really curious, and I never found that anywhere else. It’s cheap to work, there’s a co-operative mentality, there’s not a hierarchy of importance. They’re more interested in what you’re showing, not the format. Now I’m quite well known, and there’s the possibility of doing longer, more expensive things. Everything’s possible there because in Berlin there are no rules. I think Germans are quite open to seeing different kinds of work. I don’t think that’s true in Canada.

Penelope Buitenhuis filmgraphy

Word Continuum 8 min super-8 1983

Disposable 14 min super-8 1984-6

Alternative Squatting 1 5 min super-8 1984

Periphery 30 min video 1985

Framed 15 min super-8 1986

Combat Not Conform 4 min super-8 1987

Indifference 20 min super-8 1988

They Shoot Pigs Don’t They? 15 min super-8 1989

Llaw 9 min super-8 1990

A Dream of Naming 7 min 1991

Trouble 92 min 1992

Pass 15 min 1994

Boulevard 95 min 1994