Originally published in Fuse, March 1980

The work of filmmakers such as Stan Brakhage, whose use of rapid camera movement and violation of the film surface itself with paint and scratching, perhaps best exemplifies the break with convention which experimental film makes. His involvement with the physical qualities of the medium led the way for more structural and formal filmmakers. Michael Snow’s Standard Time, in which a camera makes precise horizontal pans in direct conflict with the movement of the film through the camera entertains structural examinations of the nature of film and vision. But the overriding concerns of the artist/filmmaker are in the depiction and bending of spatial/temporal precepts. As Anna Gronau, co-director of the Funnel states: “In the last decade, experimental filmmakers have been looking at the nature of perception and psychological response in film as a renewed humanism appears. There is new interest in the effect of sound and language in film – areas neglected in the long fight for the autonomy of the visual image. ‘Personal’ cinema has re-emerged in the form of autobiography, either directly or as a thematic framework. And a cautious examination of narrative forms and their ramifications is beginning.” The following is an interview conducted by FUSE with Ross McLaren and Anna Gronau of the Funnel on January 13th, 1980.

FUSE: There’s been a lot of activity in experimental film since the mid-Fifties, but the Funnel didn’t begin till the late Seventies. What changes in the needs of the community gave rise to the Funnel? What was the catalyst?

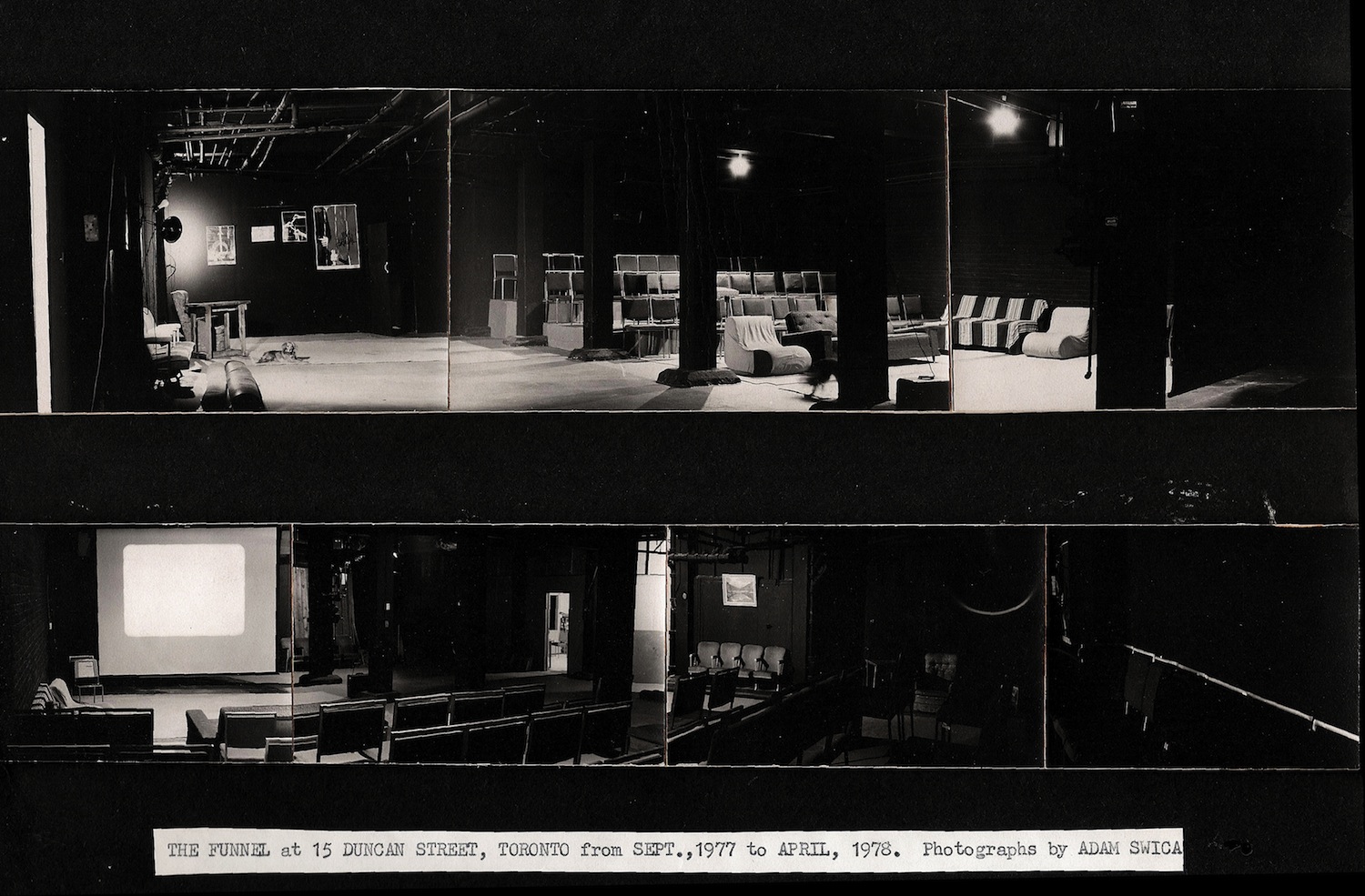

Ross McLaren: A number of experimental filmmakers were showing their work in studios and basements. We felt a need to organize some sort of forum where work could be shown publicly. Initially I started the Super 8 Film Festival. Shortly after the Festival was taken over by a number of school media studies administrators, I managed to get a local arts organization, Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC), to let us use their basement to set up a screening facility. The fall of 1977 saw our first formal screenings. I wanted to establish an autonomy from CEAC from the start, because the filmmakers were a different group of people. It wasn’t completely autonomous from CEAC because we were getting some programming money through them, but I was doing all the programming. We had our first year of screenings, getting good response and turnouts, CEAC lost their funding and their building so we found ourselves without a location. We were incorporated around the same time as we had to leave the CEAC building. But when we wrote our by-laws, we made it a membership organization and it has functioned very well on volunteer help and government arts funding. It was an experience to set up the Funnel to try to be self-sufficient. We saw what had happened to CEAC and, having been involved in the Toronto Film-Maker’s Co-op, we saw the financial problems that an arts organization can get into sometimes as a result of over-capitalization. That made us plan for a bottom-line self sufficiency.

Anna Gronau: It wasn’t just that we felt politically that we shouldn’t accept funding. We felt our reason for existence was our commitment to experimental film – regardless of whether or not we were to receive funding.

FUSE: Do you feel that you still represent the community that was the original impetus to start up the Funnel? Do you feel that you are approaching that “’five-year-crisis-point’ that all artist-run organizations seem to reach where a certain level of disenchantment with the organization on the part of the community creeps in?

RM: I’m always anticipating that; analyzing the relationship and so on. But I can’t really see it happening yet. We do have a great amount of volunteer support here from the community we represent. I don’t think there was much happening in this field really until the Toronto Film-Maker’s Co-op started in Rochdale in the early Seventies. But then, that was an all inclusive situation where all types of film were being made, unlike the Funnel. The Funnel made a definite statement that artists were working in film and that it is a different thing from industry or independent film.

AG: In the late Sixties some of the energy in experimental films in the States began to filter up. Dave Rimmer, Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland all came from New York. Films like Wavelength affected a number of film students at the time, people who were also members of the Film-Maker’s Co-op. But unfortunately the problem was that the film industry was not able to support its own people, so potential industry filmmakers would use the Co-op till they got on their feet. If, when they did get on their feet, they continued an affiliation at all, it was just for the use of facilities. It lost its co-operative aspect and became a service organization. Any workshops or seminars were technically out of league with the kind of things people like us were doing. We were alienated by their involvement in production-type films.

RM: It became an organization run by ten small businesses. They tried to accommodate industry types by buying industry-standard equipment and they went bankrupt. “Hollywood North”. The rental rates were significantly lower than standard commercial so IBM rented the equipment for six weeks in a row. But it wasn’t low enough for artists, and the Co-op certainly didn’t make any other accommodation for artists.

AG: The problem is that organizations that are profit oriented must choose profit making schemes over the well-being of the membership. The double bind is trying to maintain self-sufficiency on some level while keeping out of this trap.

RM: At the Funnel, we try to make money any way we can, but not at the expense of the programming, or access or initial direction. But then, someone once said that non-profit organizatons were doomed – you start out with a specific goal which you achieve and then you begin to get back to your work and administrators take over the wheel. Then the loss of contact with the community comes in.

FUSE: But in many ways you are becoming a lobbying front for experimental filmmakers.

RM: I think that the involvement of filmmakers in the beginning of the Funnel and in its continuation is a statement to government organizations that experimental films exist. Now that we’re a visible organization promoting this kind of activity, there is a recognition on the part of governmental agencies. It’s not intentional, but I suppose lobbying is a natural progression. It’s a role we’ll have to consider in the next three years or so.

FUSE: Yet you don’t seem to do any distribution.

RM: There’s an exchange circuit of course, and we send out packages of films by our members. This year we showed in Detroit, Ann Arbor, Houston, and we’re setting up something in Chicago and Buffalo. We have prints of films by all our members. The Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre does the majority of the distribution of experimental films in Canada.

AG: Distribution is a problem area, but there are a lot of problems in the curatorial and critical aspects of the arts in Canada. The larger institutions seem to be only interested in new mediums insofar as they are being used by artists who have proven themselves in more acceptable media. What we do is not “films by artists” – we are filmmakers.

RM: The problem with larger institutions doesn’t end there. We always run up against people who want to compare experimental filmmakers with the work of the National Film Board. The NFB is a 40 million dollar a year operation that’s running on a deficit, and it shows “Canada” to Canadians and the world at large. It’s essentially propaganda. But the really criminal thing is that they offer their films for almost nothing to the public, so a teacher will always rent 20 NFB films for very little rather than anything else because the NFB can undercut anyone else’s rates. For years we’ve been trying to get someone from the NFB down here to see what we’re doing without any luck. But funding can be a divisive force between functions of an organization as well as between disciplines. We try to define our needs and goals without worrying about slotting into the existing funding structures. We make experimental films, show them and have editing equipment and other access for making films – why not do distribution as well? We’re educating an audience we should be distributing to. Education is the key factor in getting people interested in the work. I just started teaching about a year ago. Education is the key factor in getting people interested in the work. In classes I try to de-mythologize the process and the ideas that go along with film. Filmmaking is usually treated like some kind of occult knowledge when in fact it’s a simple mechanical and chemical process. I try to show something every week and the students bring in their films. We discuss ethics and aesthetics and problems that come up in working. We talk about what art-making means, or how it fits into society or why we’re doing it. The big problem is that there’s nowhere in Toronto really that has equipment access of the kind needed. I try to tell the students that it is within financial range to own your own Super 8 or 16mm equipment. Owning it implies a different mode of filmmaking. You can work all the time, it becomes an integral part of your life. When you make a feature you have production schedules and dates and so on and you can rent equipment specifically, whereas when you own your own equipment you’re shooting all the time. We’re trying to get some equipment here that is member-only access. We’re not a community service organization or a co-op. Most of our Wintario funding went into projection equipment, but we will eventually have basic editing equipment.

FUSE: How do the screenings and programmings fit into the rest of the operation?

RM: We’ve begun a document library of post-screening discussions with the artists. We’re archiving members’ material, written and otherwise. The last Wednesday of every month we have open screenings and amazingly enough we’ve never had a dry night. There’s always enough work to show, and we will show it till we drop.