Life after Painting: an interview with Kim Tomczak (2008)

Mike: Perhaps we could begin with your name. Were you always a Kim? I can’t help thinking of Johnny Cash’s A Boy Named Sue, a tune I listened to endless summers ago in my father’s car with a mix of fascination and bewilderment. Why was my father whistling along? And however did you survive the schoolyard, the unregulated moments of childhood, wearing the name of the other gender? Or did the switch happen sometime later, when you decided to become your own parents?

Kim: I have no memory of being teased about my name as a child, it’s been much more of an issue as an adult. Rudyard Kipling’s Kim was a well-known book when I was growing up, perhaps that helped. Kim is my second name, my first is Christopher which, as you know, I don’t use. A family friend named Chrissy asked that I be named after her, my parents went along with it, but never used it. So in fact I was named after a woman, and I have a non-gender specific name. There are lots of boy and girl Kims from my generation. It got me into Maria Tippett’s By A Lady book about Canadian women artists which made me proud.

Mike: Could you spare a few words about family life? What did your parents do, beyond the full time job of parenting?

Kim: My father was a jazz musician, I call him the luckiest guy ever as he went to war as a musician in the naval band. His brother was shot down over Holland (he was part of the air force) and his other brother was blinded (in the army). My father returned unscathed.

There were five kids in the brood, small for a Catholic family. Mother stayed at home until we grew up, then she went into the clothing business. Father eventually landed a government job in Victoria, which became a pretty ideal place to grow up. We were mostly left to our own devices. I remember much biking, swimming and hiking, with a bit of school mixed in.

Mike: You’re still a jazz lover, aren’t you? Is loving jazz a way of loving your lucky father? Not that I want to get all psychoanalytic on you, but I’m wondering if you could talk about these improvised ensembles. What is the appeal exactly?

Kim: The great contradiction about jazz is that it’s actually quite formal, at least in modal form. Miles Davis and John Coltrane come to mind. Jazz has lots rules, but then so do noise bands I imagine. One of my favourite jazz moments was watching Charles Mingus in a very small club in Vancouver, there were maybe twenty five people in the audience. He was a very complex composer and his music works live much better than on vinyl. I’m grateful to have seen Miles Davis many times, always a memorable experience. Recently I have come to enjoy Bill Frisell, again live much more than recorded. He is as precise as a guitar player can get without becoming overly stylized. He can play a tune, and the tune’s harmonics at the same time, a really fascinating player.

Recently I have been listening to the complete Prestige recordings of John Coltrane, sixteen CD’s in all. I could listen to these recordings every day and never get tired of them. I don’t care for music on the go, like on an iPod. I have a theory that this type of listening is anti-music, it’s the new elevator or wallpaper music. I can’t do it very often these days because I’m too busy with this and thats, but I really like to sit in front of a pair of good speakers and just listen to a recording, hi-fi style.

Mike: Was art, or the prospect of being an artist, always part of the available repertoire of wishes when you were growing up? Or did you have your heart set in other directions? Was it your secret hope to be an oceanographer, an astronaut, a travel writer?

Kim: I was encouraged to take private art lessons from an early age that included life drawing, painting, and some sculpture. I took these lessons some evenings and Saturdays for many years and really enjoyed them. I was the only young person in the classes but my teacher, the late Jack Wilkinson, took me on and treated me like everyone else. He had a very traditional approach to art, there was lots of drawing, underpainting, learning to mix colour, and we used various thinners and varnishes. We worked out of a book at the time — I can’t remember its title — but it was like a chemistry book with all of the various formulas needed for traditional oil painting. Paintings were always made from life, instead of photographs or memory, for instance.

In the outer world, outside of these classes, the visual scene was exploding with psychedelic art, light shows and radical music — but not much of that influenced this art studio. Thinking back, I imagine it was the quiet, the focus and the support from our teacher that kept me returning week after week. In school I always took art classes, but most of them were more like timeout sessions for the other students, something easy to fill up one’s timetable. There were exceptions of course, I had a really excellent teacher in my late years of high school.

I entered art school as a painter and left never to pick up a brush again. Art was exploding in the early 70s and ideas about material-based practice ruled the day. Thankfully, I fell in with the smart crowd and we opposed the then dominant scene of abstract expressionists; we called them the gut painters because their art came from a gut level. We favoured colour field painting and studied Jack Burnham’s writings on Marcel Duchamp. Captain Beefheart and Miles were on the turntable, the French New Wave was everywhere. The Vietnam War had not wound down yet so radical politics was in the air. It was a heady time, perfect for an art student.

Vancouver was very exciting. Even larger institutions like the Vancouver Art Gallery were running experimental programs, due to the amazing curatorial brains of Alvin Balkin and Doris Shadbolt. Video art was often exhibited as sculpture, like 1973’s Sandpile , an interactive colour video sculpture by Tom Burrows that made an impact on me. It was made up of two elements, a monitor playing a tape and a pile of while sand on a table top. The video was a recording of hands forming a sand pile, it was so simple really, but there was so much to think about. How does time pass, why is repetitious movement so calming, why do we play with natural elements like sand? Seeing it in a formal gallery setting showed how this space could open to new forms.

The art school I was at started to show video a bit. In those days it was awkward but becoming possible. I remember Bruce Nauman’s work showing one day — on a monitor of course, way before projection was possible. Then the school got a Sony Portapak we could check out for the weekend, so we started slowly playing with the machines. Art and community activism crossed over a lot at that time.

The federal government was nervous about student unrest so there were funding initiatives to keep us off the streets, and from these projects we gained financial and organizational skills. There were both LIP (Local Initiatives Program) and OFY (Opportunities for Youth) grants for a five year period. Unemployment was gigantic. The programs were very liberal in their interpretation of “work,” so many kinds of arts were supported. I was lucky to be involved in a group (there were between six to eight of us) for one summer on a LIP grant. Our project involved the free distribution of artworks. We made a booth, covered it in gold mylar, and set it up every day in front of the Eaton Centre in downtown Vancouver. Somehow we got permission for this. We then handed out free artworks gathered from local artists. It had a circular sign that read CULTURE COUNTER, though of course you could also read it as COUNTER CULTURE.

Of course there was the rise of the artist-run scene which came from collectives such as Intermedia, the Grange, the Western Front, Video In and others in shared studio spaces. There was a lot of experimental culture happening, some serious, some not, but all of it added up to a vital scene. Also it was very cross-disciplinary, silos of discrete disciplines had not become so rigid as they are today.

In 1975 a group of us started an artist run centre called Pumps. We thought there was a younger voice missing from the scene, the Western Front was doing a great job, but we wanted to create something even less formal to celebrate video, experimental film and punk/new wave music. We were completely self -funded for the first several years. We had a gallery, a darkroom, and a large raw space we used for video and performance, all on the main floor. Upstairs there were bedrooms, studios, and a kitchen. It was in Gastown, on skid row, so it was very rough but fun in its own way. People came and went from Pumps, there was a core group but even that changed over the five year project. Drugs were constant. Sex was constant, yet not consistent. Bed hopping and pretty much anything you can imagine took place. And when it was over some wanted to move on while others didn’t. We eventually got some funding from the Canada Council but after five years we decided that we had done what we had set out to and it was time to move on. I lived at Pumps, along with a number of other artists. It was excitingly fraught, there was a tragic lack of funds for anything, so we had to be very inventive. Gordon Kidd put in a 16mm editing studio and we had a simple, one camera video studio. I built a darkroom. We had painting shows, experimental film screenings, big photo art shows, video exhibitions and in the last couple of years we used the first (good) video projector by Kloss. This was upsetting for the video purists who argued that video should glow from within rather than be reflected back at us like film. Needless to say, we disagreed with the purists.

I took to video slowly. I was a committed painter then, though after graduating I turned fully to video and photography and never took up a brush again. I had painted myself into a corner and it got boring for me. I was making colour field, anti-abstract expressionist work and had systematized it into an early grave. Plus the discourse around painting had ceased to be interesting. It was mumbo jumbo then and remains that way today, there really isn’t anything more to say on the subject, in my opinion. Most writing on painting is about feelings in the worst sense of the term, so I moved on to things I found more challenging.

Mike: Perhaps your shift from painting to video had something to do with a conversation you wanted to be part of, an artist’s scene that you were building and living inside. It really was a scene, wasn’t it?

Kim: Yes, and better still it was a developing scene, we made it up as we went along. It started out local, then quickly became national, even international. Correspondence art arrived, along with the guru of artist run culture — the Fluxes artist Robert Filliou. He was hugely influential to my thinking about the value and non-value of art, materiality, and its ephemeral possibilities.

My early days of video didn’t look too promising until I took a trip (by train, I recommend it to all, once) to Toronto where I saw Colin Campbell’s Modern Love, to my mind his masterpiece. This changed everything for me and on my return I made Paradise Lost which still holds up (I think). Colin, Lisa Steele and Susan Britton were very influential to my work. The idea of home-made narratives with soap opera values and techniques was so liberating to me, I just changed directions.

Mike: Video’s linear editing moment is too easily forgotten, swept away by the riptide of computer driven non-linear ease. Today it’s possible to cut a movie at home, over days or months, fixing up small and large moments anywhere in the timeline. But for years video editing was linear, meaning that every edit was more or less final, you couldn’t go back and change it without changing all the edits that followed. And the process of cutting itself was crazily difficult.

Kim: When Colin Campbell went on sabbatical Lisa (Steele) and I taught his course at the University of Toronto. He had somehow cobbled together a VHS straight cut edit suite. It had a little box as a controller, with two VHS machines: one to record, one to play. There was a twelve-step instruction sheet describing how to enter the input point on the player and an output point on the recorder. Then you had to program whether it would be an insert or assemble edit, whether you wanted audio on track one or two, and after these twelve steps miraculously an edit would occur. To get an edit lined up would take five or ten minutes, and if you did the steps in the wrong order you’d have to start again. It wasn’t frame accurate of course, it was approximate, perhaps within half a second or fifteen frames. Frame accuracy didn’t really happen until Betacam. But it was still loose and no one really cared. There was no Jubal Brown editing 5,000 cuts per second in those days. But I digress.

Mike: Could you elaborate on your early moments in video?

Kim: We started fooling around with portapacks in art school, and I was also becoming friends with Paul Wong and the artist run centre he was part of, Video In. That allowed us to borrow equipment from two places.

Mike: Was Paul a model for what an artist might be?

Kim: He was high energy cool, lots of fun and the organizer of all parties. Everything came through him. He had a kind of gang and Pumps had a kind of a gang, and sometimes the two gangs would come together and have big parties. One night his people came by and took over Pumps for an evening, dressed up like us. We had gone out for the evening, and when we got back they had rummaged through our clothes and then made a videotape which has since unfortunately vanished. Paul arrived as me and emulated the way I walked, it was hilarious. Some of the Pumps crowd were really insulted while others were amused. It was a great send up.

We collaborated with Paul. One of the artists at Pumps in those days was John Mitchell, who did sculpture and performance. He dressed up as a giant turtle and did a performance on the beach that we colour videotaped because Paul had somehow managed to acquire a colour portapack. I did the photo series that went along with it. Michael Goldberg, Paul’s mentor, wrote out a technical manual about how to run a portapack. He wanted to humanize this technical project so he wrote it out by hand. It was a text that went around the world.

Mike: Were you giving workshops?

Kim: I took workshops. Mostly they were about how to clean the heads and not damage the machine. What’s a head? The idea is that you would pass any received knowledge along to someone else. The hope was that putting tools into the hands of the people would change society. Portable video was part of the transition between hippie philosophies and a punk, political perspective. There was a lot of work done around media critique, using media as a tool for social change. The main thing that strikes me as I look back is how many collaborative things were going on. I think that occurred out of necessity, nothing happened unless people threw their weight into each other’s projects.

Mike: Video technology was both scarce and expensive in the 1980s, demanding shared ownership and access structures. Did that help drive the community structures you’re describing?

Kim: Today we still have collective production co-ops at a time when there is no scarcity of production tools. This suggests that what is important is the social aspect of production, and not the technical piece. Though it’s true that in those days you couldn’t afford the tools, a portable video camera might cost $5000, which is like $30,000 in today’s dollars.

There was also the promise of Cable TV reaching new communities for free. You could create a community-produced show on the environment, or an artistic production like John Anderson’s brainchild, The Genie Show. It was a weekly program that featured video and music centered around punk and new wave culture. There was also a great show called Gablevision, an early gay and lesbian narrowcast that came out of Vancouver. Cable TV was an expanded clubhouse. Many shows featured rubber plants in the background with two people talking in an interview format, but we’d air crazy art projects and people would see them and give feedback.

Unlike the internet where everything is on all the time so nobody ever watches anything, Cable Ten ran on Wednesday nights at 7:30pm. The whole city was cabled so you could see it anywhere. That happened here in Toronto as well, in fact Trinity Square Video (a video access organization) emerged out of a community cable show.

The cable companies provided free editing and had many different booths and video machines. We never had editing equipment at Pumps, we only used Cable Ten. You could do your own projects, it was very loose. We didn’t have censorship problems though I did hear about it. The idea was that you couldn’t show anything sexual or profane, but management never watched what we made. The United States was much more uptight, cable access came much later because the parent companies fought longer.

Mike: When I interviewed your partner Lisa she spoke about coming to Canada as part of a movement of Vietnam War resistors, and it became clear what an energizing presence this lent to the burgeoning arts and political scene here in Toronto. How did that play out in Vancouver?

Kim: We all knew draft dodgers and even some deserters. I became close to some very damaged people. They had gone to Vietnam and then deserted, and that was so radical. Leaving your country over a political issue is pretty hard, but deserting your country carried such a stigma. Most were vastly more sophisticated than we were and got jobs at the university right away. Many came before they were drafted, or in protest against the war.

Meanwhile the arts scene quickly became national. In the mid-1970s, ANNPAC (Association of National Non-Profit Centres) was formed, and I started to go to national conferences. This led to the magazine Parallelogramme. These initiatives brought everyone closer together, we compared notes about grant writing and strategies, and took our cue from Quebeckers who had a very sophisticated understanding of their cultural environment. We were at the table to learn from them. At the first ANNPAC meeting I was elected vice president, I didn’t know anything but someone had to do it. I think Clive Robertson was elected as the president, and that lasted for six months before it collapsed and reformed as something else. We all got to learn from each other.

Mike: Can you talk about other social justice momentums besides the war protests that were part of video’s early days in Vancouver?

Kim: Housing rights were important, and that showed up on cable TV as well. Vancouver is a city of rich and poor extremes. I’ve always found the invisibility of the rich in Toronto mysterious. I guess it’s because they live in the ravines. If you live in the poorest part of Vancouver you look up the hill and that’s where the rich are. Women’s rights were huge in that era, and there was a lot of attention to local music. I was a big follower of the music scene. In yesterday’s Globe (newspaper) they ran an article about the band DOA and its lead singer Joey. I knew him as Joey Shithead. Fantastic band, very energetic. Pumps was a place that bands would play. And if there was anything live we would try to videotape it. A lot of that work was destroyed in a fire unfortunately, but the remains exist in the Pumps archive at the Belkin Gallery at the University of British Columbia. We recorded poetry readings, jazz and punk outfits. Al Neil was a free jazz player, almost a noise musician at the time. He had come from a straight jazz background and took a very radical turn. Wonderful guy and performer, a genius. He could play completely drunk and remain note perfect. He’d finish a set and then fall off the stool. I’d never seen substance abuse like that, it gives you pause. In the end he outlived everybody, it was crazy.

If we didn’t videotape events we photographed them. Documentation was definitely important, we believed that something significant was being built and that we should record it along the way. We’d gone from no gallery access to us controlling the scene. Plus there was this national thing happening. It seemed that we had turned things around and were on a roll. No one cared about selling to the market… well, I guess some did. Jeff Wall and company figured that out early. Jeff and Rodney Graham were in a band called the U-Jerks, and we would go and see them play. We all knew each other. It’s still quite a small scene in Vancouver, you can take it in during a long weekend, but in Toronto it’s monstrously complex, there’s artists here I haven’t seen in years.

Mike: It’s interesting to hear you speak about these early video moments. In contrast to a painting process where you might rework encounters in a lonely studio, video feels relational, part of a community-building project. It has a political impetus, a musical lens, and a sense of process instead of finished display items. The documentation tapes seem less important as perfectly realized art objects than as records of a moment, a gathering of material. I’m hearing you shift from a traditional fine arts practice to something else.

Kim: The de-materialization of the art object was developing at that time. It wasn’t so much that we were against something, it just seemed more interesting to do collective and process-based projects. I did a series of public sculptures that would last for a day. Together with a small crew we would find a location and make a giant, colour-coded sculpture out of clear plastic glasses. There was no identification or claim to ownership, they would be installed and then left behind.

Then I became urgently interested in performance and was eventually curated into the Paris Biennale where I presented two performances in 1979/80. But I hated being on stage, it was the antithesis of anything I could imagine myself doing. The work was sculptural, and involved slide projections and audio. Performance allowed you to throw it all together in one lump.

There’s one I did in Vancouver, Paris and Toronto called A Demonstration of the Fear of Pain. At Pumps we lived in the middle of skid row, which used to mean alcoholics before it became heroin central on the downtown east side. We lived beside a community centre for men who would come over and chat. One of the guys was a deeply disturbed man from Holland who had survived the Second World War. He would help us with carpentry and often go on long rants. I mentally transcribed one of his explosions that speculated on how the war was funded, before turning towards his sexual abuse and eventual impotence. For the performance I hung a super 8 projector and ran a porn scene over a man’s face while he read a transcript. I created a soundtrack, and it all ran ten or fifteen minutes. It was very intense. How do wars happen? Who profits? It was a traumatized viewpoint that couldn’t be trusted, but it raised questions.

I made other performances, and eventually thought I might do this better in video with a bit more control. Performance has a lot of room for error, and being up in front of people was not my thing. My turn to video was accompanied by an interest in feminism. Looking around the art world I realized it was crazily masculine. Pumps was rightly accused of being macho and I wanted to do something that took a feminist bent. I wouldn’t call myself a feminist, if anything I could be a student of feminism, I would also want to learn something about the subject. I made a videotape called Paradise Lost (22 minutes 1980) where a young leftie encounters his old friend who has become a hippie and urges him to try LSD. He takes a trip, then later gets ready for a political meeting. He asks his girlfriend if she wouldn’t mind helping him to get everything ready. She says, “I’m sick and tired of helping you out with your friends.” He replies, “Look, this is about the war, we have to stop the war.” She says, “Fuck Vietnam, I’m sick of this, I’m sick of everything that you’re talking about and I don’t want to help you make coffee.” They have this long, horrible argument which is basically the whole tape except for the hippie part at the beginning which is really fun. It’s a satisfying project to look back on.

In 1980, after the Paris Biennale, I trekked around Europe until the dough ran out and then moved to Toronto. I told you I’d seen Colin’s Modern Love and thought “They’re having way more fun than we are, I better get in on some of that.” Radical things seemed to be happening here, it was a more politicized art scene, more rigorous.

It took me a while to get settled. Philip Monk put me in a show at A Space, and then I started working with Lisa Steele. We had both been at a conference in Winnipeg, and a jury in Ottawa before that. I really liked her energy, she’s so smart and articulate and said whatever was on her mind. She hired me to co-edit her police drama Some Call It Bad Luck (47 minutes 1982). It had been shot with two cameras which made it enormously difficult to edit. This was years before computer editing. We worked at Charles Street Video, and either Michael Brooks or Rodney had figured out a way that we could use two feeder decks, and patch them into a recorder. We had a stop watch and would count down aloud “4,3,2,1… Play.” For every single edit. No thanks to me, it’s a fantastic piece, so gripping and well written.

Working together was a great experience and then one of us was commissioned to do a performance at a festival in Boston. In the Dark was about the problematics of sexual representation at the time. It featured us having sex on the screen, while we sat in the audience and whispered prepared texts into microphones. When the lights come up the audience sees that we’re sitting with them, and then we speak together. It went over quite well. It came to Harbourfront for a three night run but we were cancelled after the opening with a lawyer’s letter saying that we’d violated the law. This performance locked in our collaboration, we were now in serious territory.

The early 1980s was marked by censorship and anti-censorship struggles that divided the arts community. The Funnel film theatre was tortured by the Censor Board for years, A Space Gallery was raided. A lot of political action was created to try to push back against the Board’s control. They had vague and arbitrary rulings that said, for instance, that Michael Show could show his movie at the Art Gallery of Ontario, but not at the Funnel. These are decisions you can’t let fly in a democratic society. And alongside state repression came a discourse that insisted that any kind of sexual representation was a demonstration of male power. We created our piece to suggest that there were different ways of showing and talking about sex, especially if it’s self-represented.

Mike: Could you talk about the beginnings of Vtape, one of the largest video art distributors in the world?

Kim: It really starts with Art Metropole who were probably the first real video art distributor in the world. They were early, prescient, important. My tapes were at Video In and I was invited to move to Art Metropole, but there was something about it that didn’t sit quite right with me. Perhaps it was something left over from the punk days, but I thought it’s a bit too fancy here. It wasn’t really, but that’s how I felt, so I kept my work at Video In.

Mike: Art Metropole had a curated collection and the number of artists they distributed was very small.

Kim: They had very good work but you had to be invited. Around the same time, five really important artists withdrew their tapes and formed Vtape: Rodney Werden, Susan Britton, Clive Robertson, Lisa Steele and Colin Campbell. I went back to Art Metropole and asked: what are you going to do now that your stars are gone? They said: we’ve got lots of stars. I started talking to Rodney, who was the main organizer keeping the five together as a co-operative at that point. You could preview work at someone’s house, but the project was quickly outgrowing itself. Rodney said that we needed an inclusive, computer-based system that could expand forever. It was really his idea, but he didn’t want to do it. After getting his permission, Lisa and I applied for a research grant from the Department of Communications. We spent the next year and a half talking to media users – Audio Visual librarians, curators, museum directors, people in France, England, and the United States. Mainframe computers were available but desktops were just entering the scene. No one had written any software for media databases, though three or four different centres were working on it and we were going to follow their lead. It was really fun. We got back in Toronto in 1983 and started Vtape proper.

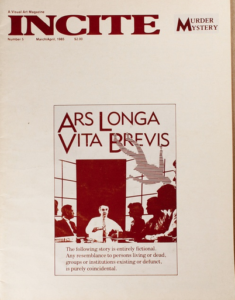

Somewhere in between we did a magazine called Incite. We rounded up a bunch of artists who had been involved with Fuse Magazine and formed our own magazine that ran for five or six issues. It was small and radical and featured artist’s projects. A freaking labour of love. Working on a magazine collectively is not the way to go, you need a boss. But we were determined to work together at a moment when there was no computer layout, there was barely typesetting. It was really great. We received some grants and then were kicked out of the granting system because the magazine was considered too political.

Incite went away but left us with a non-profit charter for The Canadian Cultural Workers Network. That became the legal name for Vtape, which is our operating name. We wanted to be as open as possible. The practice we were critical of was that when curators, festival programmers or educators went to an existing distributor like Electronic Arts Intermix or Art Metropole (and there were very few distributors then) they found a pre-curated selection of work. In a sense, your selection was already done for you. We thought there had to be a better way, there’s so much more work out there. How can we make it accessible? The missing link was the free flow of information. Our idea was that any curator or programmer should be able to get a really good description of anything that had been made.

Once again we travelled across the country interviewing artists and collecting information. That’s why in the Vtape data base, 001 is Elizabeth Vander Zaag and 002 is Sara Diamond, both from Vancouver. We started in Vancouver and worked our way east. We didn’t care whether the tapes had another distributor or not, we wanted a centralized data base so an educator could ask: what have you got on lesbian and gay issues? And there would be three hundred tapes instead of three. That’s how it started. Distribution reliability was not optimal so we took on the role of delivering actual cassettes instead of just providing information. That wasn’t part of our early design, we simply wanted to compile a data base that would point clients to the tapes, but because that didn’t work we now have 7,000 titles.

During the early 1990s Art Metropole decided that videotapes were a kind of multiple instead of an art objects, so they went into VHS home distribution. We were selling tapes to galleries for $800, while they would charge $65. But eventually the VHS revolution wound down. We’ve seen a lot of revolutions over the years. But none of them really touched this fundamental question: what do you do about the work that nobody wants to see?

Vtape had a very tough beginning, it was a slow build. Lisa was always devoted to it, but we always had other jobs. The Canada Council was extremely hesitant to give us money. The Ontario Arts Council gave us grants and then denied us. Eventually the revenues were so significant that they couldn’t ignore us, and funding has stabilized for the last fifteen years. We’re thirty years old now. And we have depth, someone can dive into the collection and come out weeks later and say, “Wow, I can’t imagine that’s what they did in 1978.” Today we’re working to restore and recuperate old formats, creating guidelines for how to keep this media alive.