Panic Bodies: The tragedy of the temporal dominates the work of this gifted Canadian experimental filmmaker by Gary Morris (Bright Lights Film Journal, April 1999, Issue 24)

In the opening segment of Panic Bodies (1998) Canadian filmmaker Mike Hoolboom talks poetically about the inevitable sense of displacement that accompanied his HIV diagnosis: “I felt like a virus that’s come to rest in this body for awhile.” But Hoolboom is no ordinary filmmaker, and Panic Bodies never succumbs to the gross sentimentality that marks much of “AIDS cinema.” He in fact finds a curious solace in his betrayer, as if a kind of body logic and pathos coexist with the disease: “My life possessed a shape after all, a unity, and that shape was my body.”

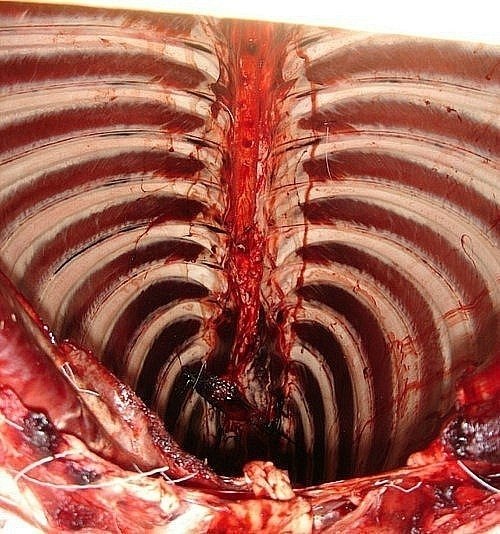

The beauty of the body and its tragic temporality are the driving motifs of this powerful six-part experimental feature (70 minutes). The opening segment Positiv, splits the screen into four smaller ones, with one occupied by Hoolboom monologing about AIDS and the other three filled with such varied treats as home movies, found footage, porn samples, microscopy and pop culture imagery from Michael Jackson to Terminator 2. Hoolboom is sometimes serious and sometimes mocking in his words (“I wanted to be a fat ice cream queen with nice skin”) and the bright, flashing images often play off them. When he talks about how “600 cells die in the body every day, and every six years we’re a new person” one of the smaller screens show a riot of microscopic cell activity. Typical of Hoolboom’s skill is his rapid intercutting of an atomic bomb explosion with a single hand, a telling image of the kind of individual apocalypse that, for the director, is woven into modern life.

A more whimsical sensibility emerges in the next segment, A Boy’s Life. Toronto performance artist Ed Johnson appears as a naked man haunted by his childhood (seen in fractured home-movie inserts) and even more, on his prick, which he plays with so much that it falls off. While Ed is busy searching for his lost appendage, Hoolboom is playful, reminding us of Ed’s quest with a cut-out penis shape through which we see the action. Of course, this is not exactly standard light fare. A scene where Ed eats a baby doll that’s been halfway up his ass recalls Goya, while scenes of multiple Eds masturbating (seen through a kaleidoscope are as unsettling as they are amusing.

The next part, Eternity, is a 10-minute exegesis of The End, in the form of a letter from Hoolboom’s friend Tom Chomont describing the latter’s experience with “the white light after death” and his overseeing of his brother’s demise. Much of this segment was shot in near-total darkness, as befits the subject; any illumination comes from the words, which again have a simple poetic resonance: “Then just at the last, concern for someone I knew pulled me back.” Some of the works here are more accessible than others. The next segment 1+1+1 shows a drunken couple laughingly assaulted each other, dressing and undressing and generally carrying on behind Hoolboom’s opaque mise-en-scene, which consists of scratchy footage, colours that bleed all over the action, and a throbbing industrial soundtrack. But the director kindly shows us some of the same scenes again without the obscuring overlays.

Part five Moucle’s Island stars Viennese filmmaker Moucle Blackout in some of the action, but most viewers will be more intrigued by interpolated ancient footage from some forgotten Naturist epic of the 1930s. This one turns a mock-innocent boat cruise and naked volleyball game into a blissful lesbian idyll, with the coyly cavorting women an ideal symbol for Hoolboom’s obsession with the sweet moment in which the body is free, even if only in an old porn film.

The last, and longest, segment is Passing On, a lyrically typically confessional effort that encapsulates what’s preceded it. Hoolboom’s dance with death-a motif acknowledged in the medieval woodcut segues between segments-resonates in double-exposed shots of anonymous people simply crossing a square, some of them “real,” others shown as faint, literal “ghosts” co-existing with those still in the temporal present. In voice-over Hoolboom talks about the “conspiracy of chromosomes” that make up the human being, the phrase is ironic; for him, nothing is more real, or human, or felt, than what that conspiracy has created.