My Big Fat Avant-Garde Movie: Notes on Brent Coughenour’s Mysterium Cosmographicum

I think I took a couple of steps back when I first heard the words “avant-garde” come out of someone’s mouth. What did you just say? It wasn’t squeezed out a conference orifice or an academic summit, but arrived via an artist named Justin bent over his latest spraypainted confection. “What are you working on?” I asked him. “It’s my avant-garde movie.” I had imagined that the avant-garde was the province of failed revolutions past, not the steady chime of labour undertaken in the hours between real jobs and whatever passed for ordinary life.

But everything gets stranger once the vanishing point is behind us. Because now that the avant-garde is not the exclusive property of 13 dress up queens in a Zurich world war getaway, now that the digital revolution has stripped the avant world of its precious remoteness and mystery (how much better those masterpieces seemed as hushed rumours), and now that the desperate inventions of the past five decades could be served up under household pet names like “lyrical diary films” or “structural cinema,” why, just about anyone with enough cashola or deal-making smarts could finesse their way through the gauntlet of post-secondary, avant-garde type education, and come out shouldering an armful of avant-garde works signed by themselves, even blessed by some of the wizened maestros of the trade. Along with a diploma of course, signifying their readiness to anoint the generations waiting to succeed them.

What does this new avant-garde look like? Well, unsurprisingly perhaps, it often assumes the reliable shapes of the old avant-garde. At festivals and art galleries around the world, viewers are wondering: haven ‘t I seen that before? And of course they have, the losing end of the Oedipal relation is whispering code into video projectors night and day. Canonical replays in classrooms and museums, along with consumer video’s plunging price points has allowed an unprecedented image promiscuity to stockpile on digital channels in a wallow of too muchness, and the avant-garde, once the exception to every exception, has followed right along. Every kind of making can be found today, and often in great abundance. There are roomfuls of new genres, or genre hybrids, like diary fictional essays, or cold wave post-op nature scans. And yet. There are some makers whose work defies even these increasingly elastic categories. Call it outsider art made by those in the know. Hoser formalism. The prime example may be Milwaukee’s Brent Coughenour.

When I met him he was a William Basinski freak. He of the 1980s tape loops rolling as the emulsion peeled from their spines, creating sticky, decaying oral bliss shallows in extreme slow motion. Brent would run those disintegrating loops until the shine dropped from their exhausted grooves, so serious about repetition being a form of change that he created his own new and improved version in a CD with an unrepeatable Russian title (why Russian?), and the English moniker: Everyone’s ugly with his/her skin peeled off. It was a carefully composed, deeply felt long form work that felt like someone reading their own gravestone on a planet where boys would spend the first ten years of their life lifting a fork and the next ten years putting it down again. The second (and final) track featured a guitar and drums, like some hold over from a life of rock star dreams that lay smothered beneath the layers of reverbed happiness. Even here Brent was not content to follow a single road not taken, but felt compelled to haul his own unwanted origins forward, and rub them uneasily against a cooler, more presentable formalism.

Ten years later, having survived a pair of abject-celebrating features and the trials of graduate school, he has warmed up a trio of found footage offerings. After a decade of negotiating the world outside his window with the new joys and sensitivities made possible with his recording machines, it was time to plunge into the digital riptide. In the words of the bard: “Everybody’s gone surfing, surfing USA.”

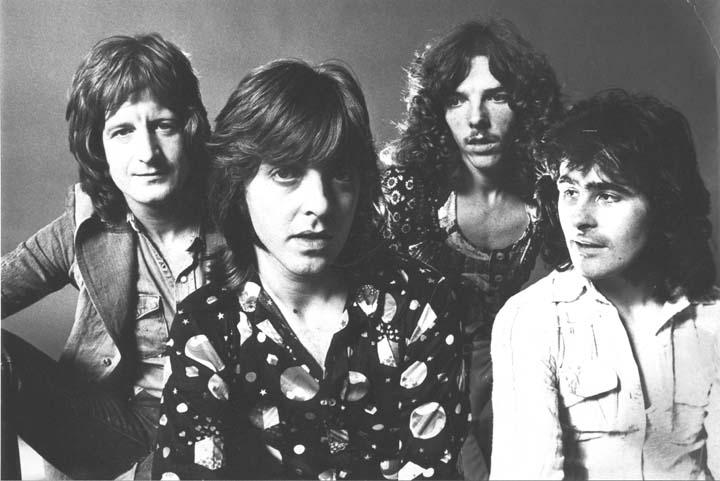

The Physical Impossibility of Life in the Mind of Someone Dead (51 minutes, 2010) turns around Badfinger’s endless chart topper Without You. Penned by a pair of musicians with girlfriend distress, and relegated to the back end of an early 70s record, it was recovered by no fewer than 180 artists who turned it into a reliable hit machine. But the cost of success proved too much for the men who wrote “I can’t live, if living is without you,” and both writers committed suicide within a decade of the song’s initial delivery. Coughenour lays out this tragedy in a series of kitsch maneuvers, reaching for the high notes in a deliriously toxic cocktail of low-brow, mass culture manias.

The Physical Impossibility proceeds in an interruptive, channel surfing mélange of internet moments, science docs and Hollywood excerpts. It is a sideways essay about masculinity, or at least, a preening, forever ejaculating, heart in my mouth, shouted-out-loud maleness whose feelings (too long deferred or projected onto any girlfriend-mother that happens to be around) can at last be expressed. I feel so bad I feel good. Or else: I’m dying, can’t you see that? Can’t you help me?

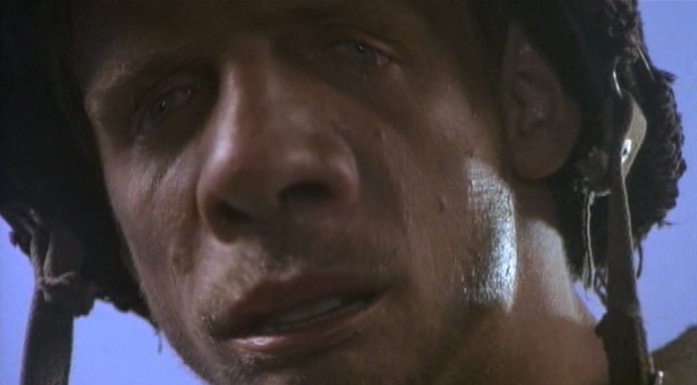

How do men appear in Brent’s potpourri of received wisdoms? His sampling of available models offer viral media templates that are predictably lonely, haunted and violent. Until they reach out of their man-cave and acknowledge that they are sharing the world with another beating heart. If the isolation is a routine, another learned response, so is the breaking of that isolation, hence the prolix use of media avatars. The pictures are us, so why not just reach for the most gruesomely familiar examples and lather up these contact narratives (between lonely detectives and their loving waiting spouses) with full-on kitsch crescendos and oral sequins? John Travolta hugs Joan Cruise in a homestead reunion in Face/Off (Travolta’s body was stolen by a master criminal, now he is “himself” again, and the unwhole family can attempt to step across the new fissures of their old identities). Tom Cruise hugs a mensch on the street. Sylvester Stallone empties machine gun rounds into a computer-filled warehouse in an ecstacy of auto-erotic release. I am an army of one, forever battling invisible enemies.

Coughenour returns again and again to Badfinger’s original chorus, which has the two pre-suicide guitarists chirping, “I can’t live,” in an infernal loop. Here is the death drive given shape as oral prophecy, but it is also the kernel of the gloriously shameful too-muchness of a hit song that was still waiting to happen. It would take Harry Nilsson’s marzipan orchestral cover version to propel it to the top of the charts, and crucially the chorus would be ratcheted up an octave, the notes held and reveled in, and held some more, until the braying sentimentality was monumentalized so that we could all get down and worship it. Badfinger are figured as a kind of Moses figure here, a prophet who might be able to carry the tune of his people, but who would never arrive at the promised land of his own music.

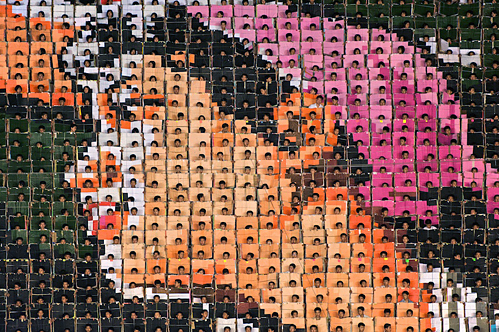

Military outfits often dot this growing mediascape, young soldiers emptying rounds into space, their faces uniformly disfigured by a selective digital stretching that enlarges their noses. These goofy grotesques seem to be shooting themselves, filled with a stunned and involuntary grieving, plunged back into the unwanted feelings of their own bodies. What are men like? Never far from death, it seems. Middle America gathers to watch a space shuttle launch only to see it explode in mid-air. Happy expectant faces turn to shock and grief. What do I do with these feelings? This body? Where do we go now?

In an incongruous segue a nature doc feature about humpback whales – beautifully recoloured by the artist – tells us that it is only the males that sing, and “Everyone sings the same song.” Could it really be true? Behind our myriad presentation models – as sons and fathers, students and teachers, employees and party goers, drivers and recreation specialists – are we all busy singing variations on the same song? And what is that song saying? According to Brent, the lines are simple enough: I am dying. With every step, every word out of my mouth, every door I open. “I can’t live.”

Youtube moments are dished up after serving time in Brent’s avant-garde hot house, every pixel shuffled and re-landscaped. Amateur cuties set themselves up in front of their computers, belting out Without You in scenes as carefully rehearsed as any award show preening, their canned sadness and off key warblings lent a reliable lo fi poignancy via multicultural reflections and bedroom framings. These flickering amateur singers are jammed into digital duets, tryads, quartets, all of them held in the same aching note. Sandwiched before and after these cover crooners are vicious clips of castration and axe murderings. What are we to do with all of these unwanted feelings? Codify them, follow the examples, allow them to become viral instants relayed via internet chain letter and then replayed in the discomfort of one’s own computer. In these home movie star turns we can follow the mannered tics of a high note taken into the body and then broadcast out again, as part of an interdependent code that Brent extends via abstract colour fields, as if one could unwrap these emotings in a symphony of mood rings.

The remorseless mainstream splatter gore, the kitsch sentimentality and overwrought emotions, the larger than life demonstrations of adolescent angst, retuned through an avant lens, offers a withering critique of the options available for masculinity. All of the movie’s dizzying electronics and treatments, in fact, a large part of the project of the avant-garde, are conjured as part of a masculine will to power that is deployed in order to channel excessive and unwanted emotings. Art making, it seems, is just another bullet in Stallone’s clip, a means of discharging anti-social rage and self loathing.

The Prognosticator or We Are All Pythagoreans Now (30 minutes 2010) is part science fair project, part avant-showroom display. It takes up thorny questions of creativity, inquiring into the relations between nature and culture. Or between imagination and math. Hysterical anti-computer tirades (“it’s the new golden calf”) rub shoulders with a doctor who claims that music’s divine harmonics are medicine, his original talking head replaced with a devil’s face. Are computers the new face of spiritual longing? Its systems and programs devised to channel every human effort? Colour flicker fields, planetary orbits, and musical computer code present themselves in a succession of vignettes. The movie closes with an extended shot showing the entrance to a nursing building on campus, with three doors on display. Two are locked, and these two are invariably tried, before the many visitors finally open the last door. It’s as if we’re watching a science experiment play out. The system works all right, unfortunately all it demonstrates is the system itself working.

These two movies are chapters in a three-headed work named Mysterium Cosmographicum. Johannes Kepler published an astronomy book under this title back in 1596, and roughly translated it means “Cosmic Mystery” or “The Secret of the World.” He imagined that math could define the underlying order of the universe; it was at once an expression of divine will, and an instrument by which we apprehend and understand that will. As an internet trolling, black-metal-loving, post-suburbanite, Brent scrapes out the media entrails of a Godless digital culture, looking for signs of what might have been named sacred, but that today appears as hacker code or masculine brio templates. In the third chapter of his trilogy, Ouroboros: Music of the Spheres (20 minutes 2011) a stuttering digital hilarity assures us that when we laugh, the universe hears us. Or at least it offers a picture of listening, which is nearly the same thing. A computer portal of a human absorbs television rappers hard at work programming public imaginations. Simulated teaching modules, a literalization of the boob tube and algorhythm paranoias are meted out in rapid succession as viewer avatars take note.

How does the brain process pictures? What is television, or its bastard child, the computer, actually doing to us? It seems we are engaged in a global experiment that functions like any other religion, requiring adherence and attention, ritual protocols of interactivity, communal simulations, and paradigm-shifting assumptions founded on codes that can be read and redrawn only by an invisible elite. In this curiously reflexive flicker frenzy, Brent holds a digital mirror up to our current obsessions, as the new viral technology of the home computer adopts content from superceded technologies which appear instantly nostalgic: television and movies. These outdated forms have had every narrative hope stripped and repurposed, until what remains are the skeletons of patriarchy, ready to take on new digital flesh. Women are valued only as desirable objects, either physically or emotionally, while men are techno-zombies and self-isolated experts. While the movie’s title announces a “music of the spheres,” this usually refers to planet orbits which were imagined to have a harmonious mathematical interval. But the society of the spectacle has reduced every expressive possibility into digital artifacts waiting to be downloaded. Now there are only screens within screens, as viewers disappear into a virtual universe of borrowed pictures, showing emotions we used to have, offering experiences that were once ours, before the pictures got to them first. What can we do except keeping watching? Even the hippest are only making pictures of this watching. Call it a science fiction dystopia of the present. A ghost of a protest still shaking its rattle deep inside the machine, offering the disused or underlooked traditions of the avant-garde as a way out of the endless feedback loop that appears as a parody of infinity. Transcendence may be a thing of the past, but not dissent. Turn on, tune in, and keep cutting. There are many ways left to say no.