Canadian Artist Spotlight: Ross McLaren by Eldon Garnet

(Originally published in Images Festival Catalogue, April 2010)

I knew Ross as a filmmaker, collaborator and the founder of the Funnel, the most important locale for experimental film in Canada. It wasn’t just the man’s charm, but his films — awkward, jarring, disjunctive, and, of course, ironic — which grabbed my attention. It was the late 1970s. It was punk. No one followed, everyone did what they weren’t expected to do. No reverence for commercial film, no desire for distribution. You made films because they needed to be made. Why not try it this way; let’s see what it looks like. A failure in film was a celebrated success. And there was Ross, a Sudbury boy in Toronto, recently graduated from the Ontario College of Art. McLaren began his career co-founding the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival, the first in Canada. His film Weather Building (1976) is emblematic of this period. Super 8, edited in camera, science fiction meets visual abstraction. It is a dissolving, collapsing, repeating visual. It is the antithesis of Warhol’s ponderous Empire State and a sly homage to Michael Snow’s incessant panning camera. With its off-screen sounds, footsteps, wind blowing, there is an uncomfortable energy in Weather Building, and simultaneously something very cerebral in its abstracted imagery. The film is an enunciation of the time.

It is 1976. McLaren is actively organizing screenings of films in the basement of the Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication (CEAC), a non-institutional, revolutionary art space operating at the edge of the edge. CEAC’s mastermind and director, Amerigo Marras, gay, young, was an architecturally trained anti-advocate for the status quo. He had grown up in radical Italian politics so, in the fresh cultural territory of Toronto art production, he was willing to open his cultural space to whatever was tough, Marxist, advocated world change, and had no time for history and its lies. Here, one was confronted. Here, in the art basement, McLaren created his seminal Crash ‘N’ Burn (1977), named after the short-lived downstairs punk club. With a wind-up 16mm Bolex, he films in silence a visual rendering of the rancorous. Jerky, rough, in grainy black-and-white, lead singer after lead singer takes off his shirt, gyrates, shakes his ass in the face of an audience who scream and jump up and down, up and down, their bodies, the camera. In the film, the audio is not synced to the visual, but this is seamless disjunction. The once-stars of early punk, the Dead Boys, Teenage Head, and the Diodes pass as McLaren zooms in and pans. It is a documentary, yet not. Scratches on the film reverberate with the snarling performers who want nothing more than to announce destruction, feign their own deaths, and draw knives across naked emaciated stomachs. The celluloid explodes in raucous frenzy: discordant, awkward, and pertinent. These are not folk singers, these are suffering punks who scream out to us: “I’m in a coma/Pull the plug on me/ I’m in a coma/please listen to me/I’ve got the right to live, I’ve got the right to die.” Isn’t this what it’s about? Kill me, it’s so fuckin’ boring.

While downstairs at CEAC the punks had screamed, five floors above Amerigo and crew organized an event for every day of the week and published Strike magazine. When Strike printed a grainy black-and-white-and-red cover photograph of Aldo Moro’s bloody body in May 1978, what occurred was a political firestorm in Conservative Ontario. Within days, all funding was withdrawn and the RCMP were at the doors. It was over in an instant. The art community went into a coma of fear; with hardly a word of protest in defense, CEAC collapsed. McLaren propels out of CEAC’s womb, tears off, landing at a small warehouse at the eastern end of Toronto where he finds a new home for the Funnel, an artist- controlled location for the making and the showing of film.

The Funnel had begun quietly after the Crash ‘n’ Burn club had shut down in the fall of 1977, operating in the CEAC basement rent-free until the 1978 incident. It was at the Funnel during the late 70s and throughout the 80s where those of us making films in the pure pleasure of self-indulgence found a supportive audience. Who cared that only a few saw your work as long as you were free to play with the media in every way possible, from over stylized narrative, to John Porter’s single frames of speed, or Michael Snow’s texts melting on found stock. It was the Funnel where you could create films for an uncompromising audience. Here, you could watch on a Friday night the latest efforts at the mutated incarnation of film. Here you could watch their films and meet some of the world’s most highly respected artists. A who’s who of the avant-garde scene exhibited and discussed their work with appearances by Kenneth Anger, Robert Frank, Warhol Superstar Ondine, James Benning, Valie Export, Jack Smith. Ross organized, promoted and made it possible for everyone to create and show their films.

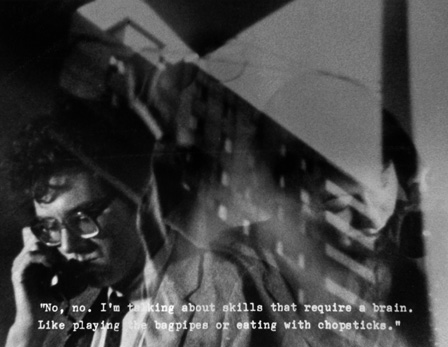

One of the first films McLaren showed at the new Funnel was Summer Camp (1978), called by the Globe and Mail’s Jay Scott: “One gruesome delusion after another. . . funny and grisly at the same time.” It is a banal, absurd film constructed of endlessly repetitive outtakes from a CBC audition for the cast of a television program, “Time of Your Life,” centering on youth culture. It is shot with a kinescope camera, an early hybrid video camera that recorded in 16mm film with an optical sound track. Each teenage actor undergoes a three-part audition: a short personal interview conducted by a prim CBC interviewer; a recital from memory of a fixed script; an improvisational dialogue with a hired CBC actor. The premise: the CBC actor portrays the brother dying of cancer. It is at this point, at the final stage of each audition, that the film takes a radical turn from a kitsch view of the amateur and the pathetic to the abject existential. The half-hearted, sweet questions of the interviewer, “What do you do in your spare time?” are replaced by the low voice from the hospital bed of the dying brother played by Peter Kastner (who later appears in Francis Ford Coppola’s You’re a Big Boy Now): “Can’t you do something to take me away from this place?” “The good times are over for us.” “It’s cancer in the final stages.” “I have three weeks to live.” So effective is Kastner that an auditioning teenager (who possibly studied in Stanislavsky technique) begins to cry, flowing tears. The humorous perversion of a 1964 CBC audition tape suddenly metamorphoses into existential angst. The banter, the empty dialogue, takes on signification: “It’s my life, it’s what I care about the most.” It is the punks again, screaming at the microphone about meaningless life and death.

Under McLaren’s direction, the Funnel was involved in the entire process of filmmaking; as important as the screening of films were the film classes and workshops. Throughout his career McLaren has been actively involved with a pedagogical approach to film. His teaching efforts began in the CEAC basement where he would run film workshops, and continue today with his active involvement in teaching film and video at a number of impressive schools in New York, at Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, Fordham University, and Millennium Film Workshop. It is this impulse to foster artistic talent which was at the core of the Funnel. Many filmmakers and artists had their first public exposure at the Funnel Gallery and screening room. Ironically, some of Ross’ students have gone on to make commercially successful feature films and have been nominated for Academy Awards.

McLaren has been steadfast in his “shrug-of-the-shoulders” rejection of the conventions of narrative film. Not-quite-orthodox structuralism, his films help in pointing to the possibilities beyond standard film conventions. A film he made in the late 1970s, Wednesday January 17, 1979 (1979) is a perfect example of the other possibilities of film. McLaren is working at the Canadian Film Distribution Centre cleaning up the heads and tails of films, taking off the old leader and adding fresh leader when he notices the leaders are often more interesting than the films. So, he splices them together, includes dates in rough Letraset, includes a final date in the future (Monday October 18,1988), and includes one three-second representational visual, part of a clock. It was all about appropriation, so why not the refuse from the waste bin, celluloid without an image, leaders brought together? And suddenly in the rhythm of the projector, in the scribbles and scratches, life appears.

McLaren’s microfiche film, 9×12 (1981), produced as an insert for Impulse magazine, is almost orthodox structuralism. Shot in the Funnel gallery space, the microfiche card consists of nine rows of 16mm film, 12 frames per row, which when placed together form a still image of the visual space and when projected display the space deconstructed through time.

In Sex Without Glasses (1983), a mannerist play on the Hollywood rear projection process shot, there is a scene where McLaren portrays himself floating above the world. With closed eyes the somnambulist filmmaker floats over a giraffe, over the moon, over the crawling insects, a shadow, a silhouette of the artist. It is film noir with irreverent humour. A man standing in a leather coat with eyes closed, the sound of rain, a black shadow passes, the man walks off screen. There is no sex, and hardly any glasses in this movie. But there are shadows in the background, rain in the dark, and many distant, barely visual, out-of-focus images which invoke a dark, postcard view of life and death. A woman looks at the sea, a man drives, Niagara Falls flows backwards, a man and a woman embrace in an erotic slide into the rushing water. In the final scene a young couple in bathing suits stand facing the ocean, she cups her hand and whispers into the boy’s ear, we don’t hear what she says, they walk off screen together. Sex Without Glasses is quintessential Funnel filmmaking; an abstract tale told with an implied narrative, seminal McLaren. It is film that employs visual effects, but primarily is constructed in existential bathos. There is humour, but in a deadpan abject colour.

The dying brother in Summer Camp tries with futility to illicit sympathetic responses from his auditioning partners, but with amateur superficiality only receives incredulous attempts at sympathy: “You’ll be ok. It’s probably an error. You aren’t really dying.” But he is. The film leaders with their indecipherable text and scratches are the evidence of the ravishes of time on our waste bin-appropriated lives. McLaren may appear on the surface as humourous, repetitive, deadpan, but something is amiss, as the voices don’t sync with the visuals, so McLaren’s message isn’t about aesthetic breakage and formulaic manipulation, but finally about the water flowing backwards, the brother dying and the sexless bodies looking out into the artificiality of the process shot.

— Eldon Garnet

For over thirty years, Ross McLaren has worked as a filmmaker, scholar, teacher,and curator. In his native Canada, he founded and was first director of the Funnel Film Centre in Toronto, an institution devoted to the production, exhibition, and distribution of film. Currently, McLaren teaches film and video courses at Cooper Union, Fordham University, the Millennium Film Workshop, and Pratt Institute. McLaren is an alumnus of the Ontario College of Art in Toronto. McLaren has shown his works worldwide. His films screened at the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris), Documenta VI, the Biennale du Paris XI and XII, the Third Annual Avant-Garde Film Festival (London), Avant Garde Film Practice: Six Views at the Pacific Cinémathèque (Vancouver), and the Ann Arbor, Edinburgh, Oberhausen, and Toronto Film Festivals. Works are included in the permanent collections of the American Federation of Arts, the Arts Council of Great Britain, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the National Film Archives (Ottawa), and the National Gallery of Canada

Eldon Garnet is an artist and writer based in Toronto. He exhibits his photographic and sculptural work internationally. He was the editor of IMPULSE, an international magazine of art, ideas and fashion. His most recent novel is Lost Between the Edges published by Semiotext(e), MIT, New York.

Michaelle McLean, John Porter, Ross McLaren, Anna Gronau in The Funnel theatre. Photos by Edie Steiner

The Funnel and Me by Ross McLaren

From catalogue: Toronto: A Play of History, Toronto: The Power Plant, 1987

The following is a personal reflection on my experiences in the Toronto film community over the last ten years. It is not meant to be an objective, theoretically-based analysis but a history, written with the realization that otherwise these events might not be recorded, given an arts scene whose memory is somewhat selective. It is also important to note that my experience as an artist/filmmaker is closely tied to the history of The Funnel Film Theatre which I founded in 1977.

Originally, my intention was to construct a media centre for the production, exhibition and distribution of film, art or whatever happened to congeal and mutate. As the long suffering debate over the Canadian film identity festered in the alphabet soup of organizational CFDCBCFINBB’s I thought a happy solution might be to forge a film gallery in some warehouse pace and actually develop an audience for these orphaned film gems. A live-in basement space was generously donated by the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC) and for one glorious year I lived a boiler-room existence while building an eager audience for these challenging works. Everything seemed to be progressing smoothly until CEAC, on a trumped-up terrorism charge, had its arms-length government funding hacked off at the shoulder. Kneecappers kneecapped! Carefully dodging RCMP phone taps, The Funnel friends of film somehow managed to prove we were not, in fact, members of the Red Brigade, and regrouped in a new location.

The word ‘Funnel’ seemed to be a good name for what we were doing. I needed an ‘F’ word to go with ‘film,’ and I also like the ambiguity associated with it. Anything could happen at The Funnel, and often did. Because The Funnel was Canada’s only ongoing showcase for independent and experimental film work, I felt a curatorial diversity was essential. Otherwise, the potential conflict of interest inherent in filmmakers who curate might result in shameless self-promotion. This has far too often been the case in Canadian experimental film programming.

During my three years as Programmer, I tried to maintain a balanced menu of international, Canadian and local work. Monthly open screenings where anyone could project absolutely anything in a spontaneous, informal context served as an important forum for works-in-progress and for discovering new talent. Working with a small budget and much volunteer labour we managed to raise the visibility of these films in Canada and also have our work screened internationally. Forming links with filmmakers and organizations in other countries was crucial as experimental film was getting very little recognition in the rest of Canada.

With this major step of organizing the artists’ film community, and due to the immediate popularity of the screenings, the arts councils were persuaded to lend some initial support. These organizational funds have continued over the last ten years, but production grants for individuals involved with The Funnel have been less frequent. In addition, Funnel members have rarely been asked to take part in the jury process. Juries are often comprised of commercial producers, out-of-touch academics, or filmmakers demonstrating the best lobbying talent. Considering the council’s stated policy of “a jury of one’s peers,” I regard this exclusion as a major problem.

As a result of this situation, funding seems to be flowing to fewer and fewer films and to those of a specific type. The trend leans toward conservative (whether patriarchal or feminist), redundant as opposed to innovative, largely big-budget productions that fit into a definite hierarchy, based on the master-apprentice relationship and the applicant’s academic background.

Despite this rather demoralizing context coupled with the presence of government-fed film tyrants (who did their best to discredit our efforts), The Funnel grew in responsibility, complexity and size. Due to constant battles with the Ontario Censor Board and the ever-increasing tasks involved in administering The Funnel’s expanded programs, the bureaucracy grew, resulting in Board member burn-out and committee fatigue. Although The Funnel was ideally structured as a democratic artist-run organization, the process of group decision-making has often resulted in a philosophical split with some favouring a more formal structure and others preferring an atmosphere of greater spontaneity. Amazingly enough, The Funnel has weathered many conflicts, managed to minimize excessive neurotic behaviour, and it at this time fulfilling its original mandate while preparing for the future.

Ironically, I recorded these thoughts having recently moved away from Toronto to New York City. From this vantage point, somewhat removed from the local art wars, it is apparent to me that The Funnel and the work of its members is up there in the international scene. I keep in touch, lend support where I can and look forward to its continued success.

The Funnel first general meeting at 507 King Street East and beginning the projection booth. Photos by John Porter

Films to be shown in this series:

I.E. (1976) is a film about making a film, was shot over a two-year period. At the time I thought I was shooting a remake of Man With A Movie Camera but I realize now that although the film is a record of its own making, it is also extremely autobiographical and diaristic.

Crash ‘n’ Burn (1977) was shot in documentary mode. This film is the only surviving filmic artifact of Canada’s first punk club – a Toronto art scene home movie. Creem Magazine praised the film for “doing everything in its flickering power to self destruct… Anyone who thought Canadians bored their beer to death ate at a different delicatessen.”

Sex Without Glasses (1983) is an amalgam of sex without guilt and sight without glasses; the importance of being able to see what you are doing. It is a film about confusing relationships, telephones and wetness, starring a preverbal somnambulist floating between words and objects.

Images Festival by Norman Wilner

Now Magazine, March 30, 2010

…And this year’s Canadian Artist Spotlight (Friday, 9 pm, at Workman Arts; rating: NNNN) showcases the combative, confrontational work of experimental filmmaker Ross McLaren, founder of Toronto’s Funnel collective in the 1970s. From 1976’s playful Weather Building to the spastic 1977 punk rock performance documentary Crash ‘N’ Burn, McLaren mixes content and form like a prankster, setting a radio interview with a cranky Jack Smith to footage of highways and train tracks in Dance Of The Sacred Foundation Application – and leaving us with the sensation that we’ve been listening to the interview while driving.

The highlight of the McLaren retrospective is Summer Camp, a surreal 1978 assemblage of kinescopes of auditions for a CBC-TV special on youth culture. As the young performers are put through their paces – giving canned responses to an interviewer, reciting a terrible monologue and then improvising a conversation with a depressed older brother who reveals he’s dying of cancer – their prepared sunniness collides with the darkness of the material, shattering the facade of fresh-faced Canadian youth. It’s deeply disturbing stuff, vividly alive in the best way.

**

Canadian Artist Spotlight Ross McLaren

Images Blog 5 – 2010 Andrew James Paterson

Ross McLaren is a very good choice for a spotlighted Canadian artist since (a) he was the maker of a significant body of cinematic works that stand tests of time very effectively indeed and (b) he was a prime catalyst in experimental film history, not only with respect to his own work but to, dare I say, multiple communities. McLaren could justifiably be accused of stirring up a lot of shit and then entering it into play.

If one were to time-tunnel back to the 1970s in Toronto, one could have an archaeological and archival field day with the histories of one particular building – 15 Duncan Street. This was once an office for the Ontario Liberal Party, but that is just a footnote. 15 Duncan hosted the Centre for Experimental Arts and Communications (CEAC), which was a force of beyond nature in its whirlwind international performance and media-arts programming and its political provocativeness. (for further reading, check out Eldon Garnet’s informative essay in the 2010 Images catalogue and then Dot Tuer’s The CEAC was Banned in Canada – Dot Tuer, Mining the Media Archive, YYZ Books, 2005).

CEAC also embraced punk rock, and in 1977 the more punk venues the better. In the basement of 15 Duncan, The Canadian power-pop-punk band The Diodes came in and organized The Crash and Burn, which was short-lived and furious. I myself remember punk/art crossover – not only the frenetic bands but also punk fashion shows and then cold beer in a metal bathtub. (for further reading, check out Liz Worth, Treat Me Like Dirt – An Oral History of Toronto Punk, Bongo Beat Books, 2009)

McLaren had begun organizing film screenings in the 15 Duncan basement in 1976. Many of the filmmakers involved were working with low-gauge stocks – Regular and Super 8 in particular. McLaren co-founded the Toronto Super-8 Festival, and he himself used the stock. McLaren had discreetly initiated The Funnel, a proto-artist-controlled organization for the making and exhibiting of film. The Funnel began in 1977, it used the former Crash and Burn space until CEAC had to shut down in 1978, and then McLaren moved the organization to a warehouse at 507 King Street East – very east indeed from most of the downtown artist-run galleries and video cooperatives. The Funnel talked and made serious film, and someone should write a book about all of this. (further reading, check out John Porter’s Super-8 Porter website)

McLaren himself has been a playful and even confrontational filmmaker, and the Images spotlight focuses on his work between 1976 and 1984, before his relocation to New York City where he continued to work and teach. Weather Building (1976) is raw and performative. Shot on Super-8 with in-camera editing, McLaren references but dances around Warhol’s Empire State. Weather Building is notable for its viscerality and its rhythms – the omnipresent footsteps are on the verge of serious crashing. The filmmaker’s body dances with his camera – somewhere between the pogo and the freefall. Weather Building, with its DIY kineticism, anticipates the punks who McLaren came to share space with and who supplied a subject for his subsequent film Crash and Burn.

McLaren indeed shares the structuralists’ concentration on the film medium’s materials. In Wednesday January 17, 1979 (Art’s birthday, according to Robert Filiou), the filmmaker is cleaning the shelves and their stock at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre when he decides that the leader of the films is more interesting than the images being led to. So then, McLaren splices the strands of leader into a filmic entity, adding dates with that convenience of punk postering – Letraset. The film 9 x 12 (1981) was produced as an microfiche insert for an edition of Impulse magazine. McLaren has assembled nine rows of 16mm. film with 12 frames per row, producing a still image of the Funnel gallery space. When projected, one can see that space deconstructed though time – one day it was this and the next day it was that.

In addition to his amusing essay on rear-screen projection and romantic narratives Sex Without Glasses (1983), McLaren screened a predominately abstract (with serious scratching) film tied to a rollercoaster radio interview with visiting luminance Jack Smith (he of Flaming Creatures notoriety). Smith is explaining why he is doing a performance and not a film during his residency at the Funnel – it is because censorship has indeed become a hot button issue since the provincial censor board has been demanding prior submission for classification of all films of all gauges to be screened in the province. The Funnel had already been hit hard by this ridiculous request, with serious legal and financial consequences. By this time, video artists and distributors and art galleries had joined the anti-censorship battle. Smith himself is alternately angry and bored with the subject, and McLaren’s “translations” of his responses to the interview almost comically follow the visiting artist’s oscillations. Now there is clarity, and now static.

The final hour of McLaren’s screening was reserved for his 1978 film Summer Camp. At sixty minutes, Summer Camp is indeed a feature, of the durational variety. This film is indeed a Duchampian exercise in importing found material into an originally-unintended venue or location. McLaren found more than several reels of young “actors” auditioning for a CBC youth culture programme called “Time of Your Life“. The auditions are, of course, repetitive. Each candidate is interviewed by a classically prim CBC employee, then asked to deliver a specific memorized speech about the grotesque cook at summer camp, and then required to perform an improvisation with a CBC actor. The CBC actor portrays the brother who is dying of cancer – he has been told by the doctors that he has three weeks remaining. So how to the candidates react to this news? Well, some already know but are still in denial. And some try to reassure the brother that the doctors can’t possibly know what the hell they’re talking about. There are interesting collisions here between different definitions of “acting”. There are clashes between annoyingly sunny dispositions and grim hospital realities. There are moments when “acting” indeed breaks down.

But… Duchamp inserted a readymade (of course a urinal) into an environment (an art gallery) in which high culture was certainly not supposed to mix with bodily fluids but in which many of the objects on the wall and the floor could be derogatively referred to as “shit”. McLaren is inserting a readymade (a CBC audition tape) into an environment in which narrative tends to be frowned on, actors are considered to be generally unnecessary, and television itself is an inhabitant of another planet. (And video is suspected by some to be a poor cousin of television) If McLaren had mounted Summer Camp as a gallery installation, then people would look at it, get the point, and move on; or else move around the installation while checking in on the “narrative’ at their own speed. Perhaps they might form their own coteries of comic observers – perhaps the installation might become proto-“relational” or whatever. In a cinematic or theatrical screening situation, a tension develops between quick over-familiarity with the structure and the tacit agreement to commit oneself to the strictures of duration. Summer Camp problematizes art/cinematic/ television boundaries by its very everydayness – its blandness and relative monotony. The scene with the dying brother could possibly be shot as flaming melodrama, but this is just an audition tape and visuals are not a priority. Structural exercises make their points quickly and then must complete their own executions – those are the rules of their games.

And so Summer Camp indeed played as a feature that itself had started late. Audiences were more than trickling in for the evening’s finale – a karaoke screening of McLaren’s 1977 film Crash and Burn. Yes, the old punks were beginning to fill the room. And a found-footage CBC audition tape was beginning to resemble a present-day reality-TV show in which none of the contestants were particularly suitable star material.

So, there we go. And again, congratulations to the Images Festival for an astute choice of featured Canadian artist. I made a quick decision that staying for the karaoke might be hard on my implanted tinnitus, and I walked home. It was prematurely summer, and not at all camp.

**

Art born of frustration by Peter Goddard

Published in Toronto Star, Sunday Mar 28 2010

The big draw Friday at the Images Festival’s “Canadian Artist Spotlight: Ross McLaren” will likely be Crash ’n’ Burn Karaoke!, featuring the veteran video guru’s grainy homage to Toronto’s fabulously infamous downtown punk joint and some of the bands it presented: Teenage Head, Dead Boys and Diodes.

But Summer Camp (1978) should cause the greatest stir from among the seven screenings from the former Toronto-based video artist and teacher. (Born in Sudbury in 1953, McLaren has taught at Cooper Union and other New York area schools since 1986.)

Punk’s stylized sonic and visual violence in Crash ’n’ Burn — shot by McLaren using a 16mm windup Bolex camera — today feels as comfortably familiar as an Herb Alpert tribute on Easy Listening radio. Maybe that’s why Images is doing a karaoke version.

“It’s not meant to be nostalgic,” he warns on the phone from his office. “Nothing is more pathetic than punk nostalgia. I think of the film as being Cubist. A band goes through three costume changes in one song.”

Summer Camp has a comic creepiness that gets further distilled, down to something bordering on the malevolent.

A mélange of outtakes from auditions left over from a 1964 CBC “youth” show, Time of Your Life, Summer Camp shows a series of wannabe actors — their names now forgotten by McLaren — sitting pluckily through a three-part test on camera.

Each actor is interviewed by a tall, prim woman whose perfect diction is pure self-parody and whose condescending demeanour sucks the life out of the studio.

“You look like Kate Reid,” she tells the freckle-faced Joann, who is so befuddled at one point she claims to have once seen “King John the 23rd” at Stratford.

Yes indeed, Joanne is just like a “younger” Kate Reid, “and thinner,” says the interviewer.

Such mean-spiritedness seeps through the second part of the audition — where each aspirant must recite identical lines from a drama set in a summer camp — and into the third section, where each is joined on camera by another character, played by the late Peter Kastner, who unexpectedly announces he’s dying from cancer.

Some of the hopefuls react in shock. Not so the ever-perky Joann. “You’re in the hospital. No worry,” she says, adding with feigned envy, “and me in school.”

In McLaren’s unsparingly observed world, the CBC is its own sort of summer camp, “not paying much attention to anything but itself,” he says. “Summer Camp is my way of giving the finger to the CBC, of making fun of it. Yet some people have run screaming from the screening of it.”

Punk’s arrival in Toronto in the mid-’70s was more than a local response to a worldwide phenomenon. Toronto punk — for all its nostalgia for rock’s photogenic roots — reflected the growing resistance to new architectural and bureaucratic intrusions into the city’s living spaces.

For McLaren and others, that meant finding their own space. They opened The Funnel Experimental Film Theatre, at 507 King St. E., in 1977 after the closing of their earlier headquarters, the Centre for Experimental Arts and Communications (CEAC) at 15 Duncan St.

Indeed, the exploration of interior space threads its way through much of McLaren’s early Toronto work. His 9 x 12 (1979-1981) creates the illusion of movement through the Funnel’s main space taken from images formally organized on an extensive set of microfiche cards. Sex Without Glasses (1983) reveals actors reacting with clumsy feigned intensity to scenes shown via a back-screen projection.

“A lot of frustration went into making these films,” says McLaren. “I was frustrated with the funding structure (of Canadian mainstream filmmaking), so I made an end run around it, and built a self-sustaining theatre, which connected with an avant-garde practice.”

“Canadian Artist Spotlight: Ross McLaren” is at Workman Arts, St. Anne’s Parish Hall, 651 Dufferin St. at Dundas St. Friday 9 p.m. Starting at 11 p.m. Crash ’n’ Burn Karaoke! will be screened. Afterward, F—– Up’s Damian Abraham will spin vintage Toronto punk rock. General admission $10, $8 for students, seniors and festival members.

**

Review: An Evening with Ross McLaren at the 2010 Images Festival

Toronto Film Scene, spring 2010 http://thetfs.ca/2010/04/04/review-an-evening-with-ross-mclaren-at-the-2010-images-festival/

If you’ve ever attended a screening or event at the Images Festival, you’ll know that its about so much more than just the films. The atmosphere and the people totally make the experience what it is. If you’ve never attended an Images event, you should start now (the festival began on April 1st this year and runs until the 10th).

This year’s Canadian Artist Spotlight is on experimental filmmaker Ross McLaren, who famously ditched Canada more than two decades ago, and currently resides in Brooklyn, where he makes films and teaches filmmaking practice. McLaren’s films are, in the notorious tradition of the avant-garde, anything but swallowable or easy to follow. Of course, you always hear that experimental films, if you give them enough time and patience, will somehow magically “reward” you. What follows is a breakdown of my Friday night with Ross McLaren and his films. Was I “rewarded”? Infinitely.

9:00 pm: McLaren makes a few opening remarks before the screening (“Unlike Jesus, I have returned.”) He has not shown a frame of film in Canada in decades.

9:15 pm – 11:00 pm: Six McLaren films are screened. First, Weather Building (1976, 16mm, 10.5 min) gives you a little taste of seizure-inducing flashing lights, creepily psychic camera movements and incomprehensible spatial orientations (Am I indoors? Outdoors? Both? But how ?). Next, we get Wednesday January 17, 1975 (1979, 16mm, 4.5 min), which is basically a deliciously indecipherable autobiography of important dates in McLaren’s life, set against the richly coloured head and tail frames cut from other (unknown) films; film stock garbage acting as diary. After this, Sex Without Glasses (1983, 16mm, 12.5 min), a hilarious and horrifying parody of rear-projection with some absurdity thrown in for kicks (sample dialogue: “I have a heart like an elephant.”) Following, 9 x 12 (1979-1981, 16mm, 1 min), a series of still frames depicting the interior of the now-defunct legendary Funnel Experimental Film Theatre. Next, Dance of the Sacred Foundation Application (2003, video, 15 min), in which a whirlwind of high-speed travel images accompany the audio of a radio interview featuring McLaren and infamous filmmaker Jack Smith. The latter tells us, among other things, how Andy Warhol’s nose was so atrophied that it looked like a machine-gun turret. I found this information fascinating. Finally, the pièce de résistance of the program: Summer Camp (1978, 16mm, 60 min). It’s basically like getting a pie thrown in your face verrry slowwwly, if the pie filling was made out of banality, disdain, embarrassment, nauseating repetition, and a cherry on top of diamond-cut wit. This is cinematic masochism at its best.

11:15 pm: The chairs are removed, drinks are for sale, and McLaren’s Crash ‘n’ Burn (1977, 16 mm) is shown with subtitles for the valiant purposes of instigating a little karaoke action (it didn’t really work). This film is one of the first punk documentaries ever made: we get saliva-spitting, stomach-cutting, wall-climbing, thrash-and-destroy performances by bands from the late ’70s Toronto punk scene like the Dead Boys, Teenage Head, the Diodes, and the Boyfriends. Lots of old punks are there. Wicked cool. A drunk guy at the bar next to me yells “I don’t want a Christian beer! Give me a Muslim beer!” And what’s that smell? Grilled cheese sandwiches. The guy serving them tries to convince me its “gourmet Bolivian cheddar”, but I know a Kraft Single when I taste one. Still pretty cool.

2:30 am (I think): I’m at another bar down the street throwing back whiskey sours and ranting about etymology to strangers. Who do I spot out of the corner of my eye but an equally-drunk Ross McLaren at the bar? I go over and make some chit-chat with him, and here is the condensed report:

He has a 27-year-old parrot named Frankie. Summer Camp is supposed to make you feel that way. Artists shouldn’t be allowed to design hotel rooms. Public servants have bad style. The best parties are always in Kensington.