Romantic: an interview with Christian Morrison (April 2013)

Christian: My favourite class at the Ontario College of Art was with Ross McLaren. I was there with my childhood friend and roommate Ian Cochrane who became very involved with the Funnel later on. We both grew up in the same small Ontario town of Almonte. Ross was still in his twenties I think, he looked like a punk, wearing a leather jacket and Doonesbury glasses and tight jeans like we all did. He looked like one of us. This is 1978-79. He would sit there, very relaxed, with one arm over the back of a chair and gas us up. As much as we all loved Michael Snow’s Wavelength he wasn’t talking about that kind of film, he was interested in transgressive cinema. It was like sitting in a room with Lou Reed only better because this guy was much younger and cooler than Lou Reed. That’s how it was for us.

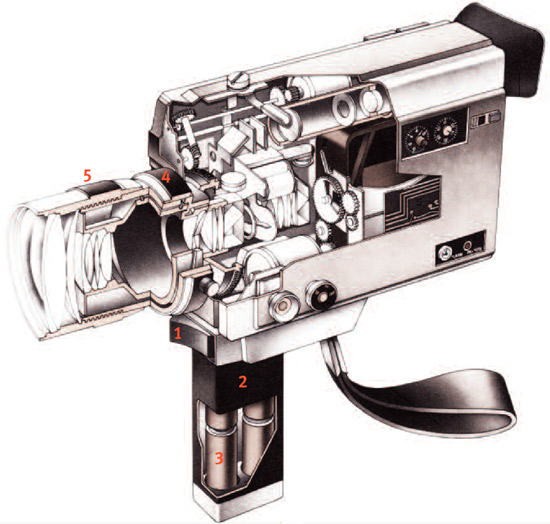

Mike: What was the feedback like?We all made work and brought it in. I don’t think there were any parameters, anything went. If it was on film, it was fine. It wasn’t easy to get video equipment out for a film class, there was a big division in the school, and there was a whole section of the college dedicated to real filmmaking. You could take out a Bolex and shoot a 16mm film with lights, or you could go to the same AV room and sign out a super 8 camera and pick up some film at the corner store. It was all so cheap back then.

Christian: It was always a bit of a mash up. We’d sit around and talk about what we’d seen. People always felt supported, that was Ross’s thing. Then he took a bunch of us to the Funnel. He said we’re doing this event, we’re having this screening, you should come. He was great at building that audience. People like Ross or John Porter were so encouraging. You could make kooky, possibly horrible films, and still feel supported.

Ross made a great film out of discarded film ends he gathered when working at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre. It was called Wednesday, January 17, 1979 (4.5 minutes, 1979). When he showed the film in class you could hear a pin drop when it was over. It appealed in that Roland Barthes/Pleasure of the Text kind of way, it played to our innate expectations as all these heads and tails of films went by. It’s unmatched for the sheer pleasure of film watching.

We talked a lot about the physicality of film. We watched Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight (1963) where he glued moth wings to clear film. I became fascinated with the physical nature of film. I was taking electronics with Norman White who taught us how to use these little processors called 555. It’s basically a clock that generates a square wave, an on/off signal. You could control it using switches, potentiometers. I figured out a way to trigger this chip with a light sensitive diode. My machine is just a little box with a light sensitive diode on the front and a knob that controls the output volume. I put it on a little stand, and then hooked it up to a guitar amp. Then I bought too much black film leader and spent a week punching holes into it. When the light came through the holes, the diode would see the light and make a small rrrr sound. If it was a big series of holes it would go RRRRRRRR! It was inspired by Ross for sure and Stan Brakhage. I premiered it at the Funnel and it drove most people out of the theatre which was really cool. When people found out I was the filmmaker they were mad at me because it was pretty long. I shortened it for a little while and then stopped showing it.

The Funnel had a very slow moving, easy going, arts administration style. Either Ross or Michelle MacLean asked us to join and become core members. Of course we said yes, and after that we went all the time. We swept the floors and took tickets at the door. Screenings were on Wednesday and Friday/Saturday. You would sign up on the calendar. Projection was also volunteer, but the more senior people did that because if you fucked up people would get mad, even if it was experimental film. It was such an exciting time. For us students The Funnel was a vortex of burning energy.

After problems with the Censor Board, city inspectors came and demanded extensive renovations to bring the building up to code. The Funnel had to be completely isolated from the rest of the building, so we had to build a box around the space made out of fire retardant drywall. The booth was sealed off so that if a projector caught fire you were able to close the door and it would burn itself out. David Bennell was in charge of construction. I think they were also using contractors, but I remember carrying the chairs out and then carrying them back in; that’s what I was good for, a big lunky kid with lots of time to spare. I would go there once a week at least, others went every day. It was a real community builder, everyone who did it felt they’d earned their stripes.

They showed such great work, if you missed an evening it was crazy, you’d kick yourself. I just loved James Benning’s films and I loved meeting him. He was a fatherly, awesome genius. He framed these beautiful landscapes and gave you time to see them and then an ice cream truck would roll through the frame creating strange narratives. I found out that he had a daughter who made films and I thought oh god, how wonderful, she would be a perfect girlfriend for me. If only she wasn’t gay. (laughs)

After the screenings people would hang out in the gallery area. You could go up to someone like Benning and say, “Oh wow, I really loved that,” or offer some asshole-ish comment that people always make about films to filmmakers, and then Ross would announce that we were all going to the Dominion Tavern. We’d drink out of stubbie bottles until last call and go home to Parkdale. Magical times. It didn’t matter if you were a person of colour, or a Japanese guy, or a guy from the Ottawa Valley. Audiences hung on your film, watched it right to the end, and after people would talk to you. From 1978-79, these were the halcyon days of early artist-run collectives. The feeling of collective spirit charged the receptivity of audiences. You couldn’t tell why the room was full of people. There might be a blizzard outside and there would be a couple of students showing work, but everyone would come out and watch. There was such energy and attention. Of course we didn’t have a TV back then, you couldn’t rent videos or troll the internet. I think the Funnel was a very romantic place. We loved it. I can’t think of anyone more beautiful than Anna or more handsome than David Bennell, they were god-like to a young student. I don’t remember any of their films, but they were so cool.

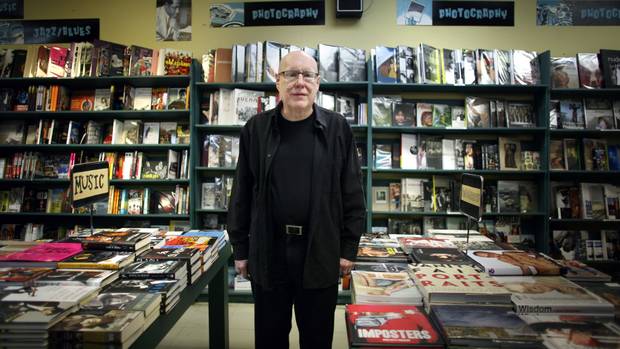

I was working at Pages Bookstores at the time, the only employee willing to open the store on Sundays. I did a performance with owner Marc Glassman. I had an uncanny ability to imitate William Burroughs and pretty well memorized everything he’d written. I could do Bukowski too, I loved these transgressive writers. Marc and I sat in two chairs with films running behind us. It was goofy, fun and literary.

Some of our shows were musical. Mark DeGuerre, Ed Lam and I would get together and project films and make noise. At the end of the cold war there was a brief apocalyptic period where everyone thought the world was going to end in a nuclear winter, so we called the group Einstein’s Barbeque. We performed at the Art Gallery of Ontario and a church on Avenue Road and at the Funnel’s open screenings. We’d show super 8 collage movies of bombs going off.

Mike: Was it easy to show at the Funnel?

Christian: It was probably a bit cliquey. I think it was a place that was open-ended, where you could come in and find a space for yourself within the ongoing morph that was the Funnel. Some people got frustrated with that and others liked it. It wasn’t the easiest place to get a screening on a regular night, but the “Open Screenings” were accessible. The work had to be non-narrative in order to show at the Funnel.

Mike: Why did you leave?

Christian: I never left, I’m still there. Kate and I had a baby and then I got a job at Trinity Square Video as a production manager.

Mike: What was the difference between Trinity Square Video and the Funnel?

Christian: The Funnel was a theatre while Trinity was a production centre. The Funnel had a little bit of equipment, a camera or two, and of course Trinity had a screening room for members to use, but their focus was on equipment access.

There was a strong division between film and video. By the early 1980s it was easier to see video than film. I was still shooting film for the performance pieces I was doing because of its tactility and the ability to project it. Video projection was very nascent at that point. But film exhibitions had become marginalized. I can’t remember the last time I watched an experimental film since my time at the Funnel. Exhibition seemed to migrate to video. It had to do with the accessibility of the tools.

Mike: Did film seem part of the past?

Christian: Film was old fashioned. Video was contemporary, but it felt pretty old too. I remember looking at work for a review I wrote for Vanguard Magazine in 1982. Art Metropole had done a survey of video art out of their collection and I came around and watched a tape made in 1972 showing a metronome swinging back and forth in real time. There was a lot of stuff like that and it was beautiful, I have a weakness for it. Video was already a senior citizen by the eighties. Everything had started to swing towards narrative, though there was also a lot of social activism that happened in video. Trinity has a good collection of community videos documenting the Litton strike, for example. Litton treated their workers so poorly. It was a factory in North York making guidance systems for nuclear weapons, as well as filing cabinets and office equipment. Someone planted a bomb and blew up part of the plant. Artists like Phyllis Waugh and Nancy Nichol were making really great work around social political issues.

Mike: That kind of social justice work wasn’t made or seen at the Funnel. Was that a surprise?

Christian: The Funnel was more art oriented. It was concerned with the aesthetics of the film, rather than using film as a tool for social change. They didn’t show documentaries.

Mike: Was it surprising that the video community was open to those expressions?=

Christian: Not at all, the technology makes video so affordable and accessible, whereas you didn’t have a good way of making a super 8 movie with sound. Ed and I found a sound super 8 Fuji camera for $500 back in 1979. It was probably the most expensive thing I ever bought in my life. But the sound never worked. In video, even the earliest reel-to-reel decks brought sound and picture together on a single reel. It was so much easier to work with than film, which sounds awful to say, but it’s true. You didn’t have to go to school to learn how to use a video camera. You point it at something, focus it, turn it on, turn it off. The revolution had arrived.

Mike: Wasn’t the easy access and DIY sensibility at the heart of the Funnel’s hopes?

Christian: I think so. Back then it was easier to shoot super 8, take it to a lab and have it developed. You could even fill out the box and send it to Kodak and have it back in three or four days. But the labs started closing, and prices rose. Even by the early 1980s super 8 wasn’t the easiest thing to do. I remember scratching my head: where am I going to get this processed? Where can I make these loops? It wasn’t a standard anymore. Video was taking over.