Outsider’s Overture: James Carman on James Carman

I used to compose experimental computer music at the University of Texas. To present the music I raided all the documentary/science films in the Cinematheques and made videos. For me video was an accompaniment to the music, but for most images are more important than sound. The first tape was El Tunel (18 min 1985) which featured a lot of war images, abstract computer graphics, and some scenes I staged myself. It’s about sensory overload and the media, how you can’t stop anything and have to find a way in the flow. I didn’t show it much because I didn’t know I could. I started travelling again, through Northern Africa and Europe and a long Amsterdam debauch which I tried to escape by coming to Berlin. I did odd jobs, didn’t make it into the film academies, then went to India and Nepal, and came back to Berlin with a small rock opera called Outsider’s Overture. It featured electronic music, super-8 film and clunky garage band songs.

Then I went to San Francisco State and studied film for two years. Claw Your Eye (5 min 1990) was made there, my first 16mm film. It’s about a foreboding, an invocation of the second sight. It has a frenetic, demonic quality to it that builds into an orgiastic orgasm. One of my biggest fascinations is seeing into the future, sometimes I get totally obsessed with one divination system or another, trying to piece together what’s going to happen. It’s a kind of sickness, but it helps me to understand that time only appears linear, the future’s already happened.

The film is also about shadows, trying to show what you can’t show, say what you can’t say. Clawing your eye is the anguish of understanding, because the eye you see with is not the eye that understands. The film shows people being hypnotized, a man dancing in the mouth of cave with a large sombrero, shadows of children playing, young men masturbating, frenetic shadows dancing. It uses a lot of reflections because no one notices them, the reflection of this lamp here is just as real as the lamp but we don’t see it. And this lack of paying attention is metaphor or indicative of the way we don’t pay attention to other things in our physical world, like second sight or spirits. When I took more drugs I had more access to spirits, but now that I live such a healthy life (laughs) I talk to them more but they speak less. What do I say to them? Usually I just say thanks.

I didn’t finish school because they didn’t know anything about production, and a purely academic approach was too limited. Besides I liked it in Berlin. It was the easiest place to be a bohemian. You don’t have to work too hard, the rent is cheap and there’s always a lot of cultural stuff going on. I’d shot 3,000 Years of Gravity (30 min 1991) in San Francisco and edited when I came back. It’s a long terrible journey, about searching over time and not finding anything, finally a spiritual search undertaken in the wrong way. It’s set in five movements, one for each of the four directions, and the fifth was aether where he transcends, he goes to another level. Each direction is staged in a striking new landscape, and another era. It was interesting to me to make a film without telephones, cars or buildings. I wanted to make a pure film like making a film about a stone or a box or a shoe.

The actor was my roommate, a major pain in the ass. Until the film was finished we were in a weirdly dependent relationship so we both had to suffer. It’s important that people are challenged, it’s wrong to spoil actors, treat them as if they’re a precious talent. He was naked the whole time and sometimes the elements were rough, sometimes it was snowing, and once he broke down and had a fit and refused to put his clothes back on and I worried he would die of exposure. In a shamanic way, he’s looking for signs to give him direction. When you’re walking it’s a natural thing to piss and eat and shit so that’s what he does. At the end of his journey he finds a puppet on the beach. He kisses and caresses it, but gets no love in return after travelling for thousands of years. Distraught, he goes into the ocean and presumably drowns himself.

Then I shot Think Tank (18 min 1992). It’s about a guy who works in a think tank for the development of kitchen appliances and has a nervous breakdown. He goes to the company psychiatrist and she uses shamanic techniques to squeeze out the last idea he has of himself, to make him functional again. Inside his head he enters a sadomasochistic underworld, he’s put in jail and forced to build flight cases for the rest of eternity. Then he comes back to the office where the psychiatrist is sucking blood out of his chest. She indicates that he’s making progress and being cured. He goes back to work ‘selling brain,’ they call it that in the business, selling your intelligence, your ideas. He’s working with a secretary whose always ironing his clothes and typing memos and he imagines she’s ironing his dick, but everything seems normal because he asks her to take another dictation.

The people who liked this film the most worked at Microsoft. It was weird going to New York and having them throw a party for me and telling me how much they loved the film. Myself, I never worked longer than three months at a job. There used to be a magazine called Zero Hour whose motivation was to reduce the forty hour work week to zero and I was always partial to this view. My major fault as a filmmaker? I give way to my demons, instead of saying no and keeping something in control, and making the message clearer, I always give in to a demon who wants to be as devious as it can possibly be.

Mind is the Medium (2 min 1993) is a filmic haiku. We see dogs fighting, a man walking in an artificial wood which turns into a burning plain of oil, a cloud moving over a pristine field, a naked woman painted white running away from the camera frightened. It’s a montage of moments which ask that they be understood as part of one thing, an instant. I didn’t want to write an essay but to make a haiku like:

Sun rises over the Everglades.

Hamburger bun.

I was in the mountains of Brazil last New Year’s Eve. They were having a Candomble ritual, drumming all night long and going into trance possession like voodoo. I’m checking out this ritual and who do I see but Jimmy Page standing next to me. I nodded and then went inside the ritual where you have to participate, because the people who go into trance don’t discriminate, they can’t tell you’re not from the village, you’re just the next person who needs to go into trance. They would often hug or hit you which felt like a jolt of electricity. Jimmy took off but I saw him the next day with his girlfriend and baby. It was great to see him being calm, he looked happy. But later on in the evening he was very somber and solitary and looked like he was searching for direction too.

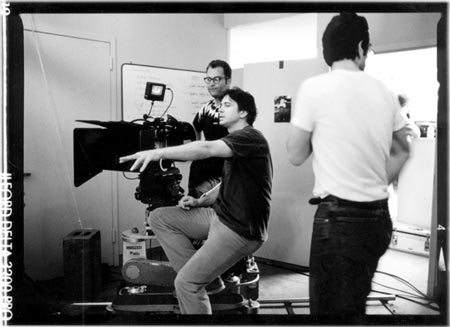

I love being out with a Bolex when there’s no pressure. I get a certain feeling in my solar plexus when I shoot and then I know it’s an image I need. Shooting is a body meditation, a feeling of being at rest and connecting.

Open Light (12 min 1996) is a film about meditation and my failure as a human being. It’s about my failure to reach any deeper spiritual reality though I’ve practiced for years, the loss of my relationship, the stupidity of sorrow and self pity. Real answers require the sacrifice of a normal life style, and most can’t give up enough time. Any sudden insights have no lasting influence, you always return to the same problems and obsessions you had before, the old traps. My film is about mediation and expresses an inability to free myself although everything is at hand, the lack of liberation another self imposed mental construct. This frustration moves into sorrow, not just self pity but weltschmerz (world’s pain), a unification with weltschmerz, and that’s the consolation prize the film offers.

The bound woman was my girlfriend whose free in the end. The other side of meditation was the woman’s bound condition. She’s very still, it doesn’t look like she’s suffering, so her bondage is a visual metaphor for the limitations we put upon ourselves. She’s woven together with images of monks meditating, bucolic nature, animal images, Mayan pyramids, and a plain of salt hills reclaimed from the sea. These images all look as if they’re passing through the mind of the monk, who finally turns his back on the viewer. The film conjures the possibility of an open light, another way of seeing the world, but this opportunity isn’t taken.

I often get flashes of films I’d like to make but I finance them myself so I don’t often get the chance. I afford them by shooting for others or going into debt, I’ve given up trying to get money for my work. I still feel like I’m an outsider here because I shoot just for my friends, and the burgeoning filmmakers here start in Film School where they have so much opportunity. For me, it’s a disadvantage not being German. I’ve found the Germans unwilling to approach visionary film, be it experimental or narrative. For me that’s the most interesting place, you have to try to do something new or striking, but they’re too safe, they don’t have the balls.

Originally published in: Millennium Film Journal No. 30/31, Fall 1997.

This edited transcript is based on an interview with Mike Hoolboom.