Dear Stephen,

I am afraid you are right about the Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011). In moments it is perfect, though flawed overall, overwrought, reaching too far, with too much of that juiced up music slathered over everything, never mind the whispering voices. I think whispering voiceovers is one of the first “you will never do this” items on the avant-gardist anti-shopping list. Along with cute pictures of cats, images of graveyards, and overly expressive musics. The entire last movement of the movie is a reach into something that’s not quite there, Stanley Kubrick solved this problem with his trip sequence and time shifting scenarios. Malick is adrift here, but even so, for me, the parts were greater than the whole. It was like having a guest come to dinner and tell some beautiful stories and then tell too many so by the end of the evening you just want him to leave. But the way Malick flicks attention across a frame, decentering it, refusing what is in the middle… Or the way he readjusts his framing in a series of jump cuts in imitation of the eye’s saccadic rhythm of scanning and rescanning. The way he introduces a dog barking around a boy and places the dog on the left corner of the frame, medium close, and then in the next shot the same dog is far away to the right and moving further, an animal life that is somehow denied the boy – there is a world in just those two sequential shots. The way the camera approaches a character while the character approaches the camera – a riff copped from Scorsese who likes to turn up a pop tune while this is happening – it’s so beautiful, like the meeting of two parallel universes. And while I didn’t warm to the dinosaurs I had to give him credit: a risky move that he allowed to play out. Not to mention where he placed it, sandwiched between Waco scenes, that was a lot of stretching.

You’ve probably seen the movies of Gus van Sant – the resurrected/revitalized Van Sant, the one who very strangely came to a wholly different style and subject of making after a very distinctly Hollywood period, with movies like Gerry and Elephant. His signature gesture in those movies was a behind the character follow shot, kept at a steady distance, it allowed him to map out spaces – the desert in Gerry, the school in Elephant – and has been a widely imitated tic ever since – the camera is handheld, on a steadicam (hence smooth), and there is both identification and a refusal of identification (no face). Malick takes up this trope gauntlet in The Tree of Life (I think for the first time, though am probably wrong here) with a consistent use of handheld steadicam shots, also made from behind the characters, but he favours a 3/4 blind – he approaches his characters at an oblique angle, so that part of their face is visible – and this provides some deep sense that they have an inkling of the immensity of their lives, or even the centre of their lives, but that there is some larger mystery “behind their back” that they can’t reckon, that is beyond them somehow. This larger mystery is religious of course, and in this sense the 3/4 blind is perhaps literally a religious perspective. Underlined by the fact that the camera is so often looking slightly upwards at its charge.

Do you remember the shots of the newlywed floating? Another perfect throwaway, it’s such an outrageous effect, right at home in kung fu thrillers, but brought now to the front lawn of small town Texas, quickly unwrapped, and then it’s onto something else, just another perfect moment to swallow. One of the first things I remember being told in film school is that you were always supposed to remove your best shots, because they would stick out, and make everything else look forced, or sub-optimal. And certainly there is nothing like this in the rest of the movie, but somehow, for me at least, it doesn’t matter. Malick plunges into this moment and such is his lightness that the movie bears it along, without much ado. Strange that for all its heaviness, it can also be so light.

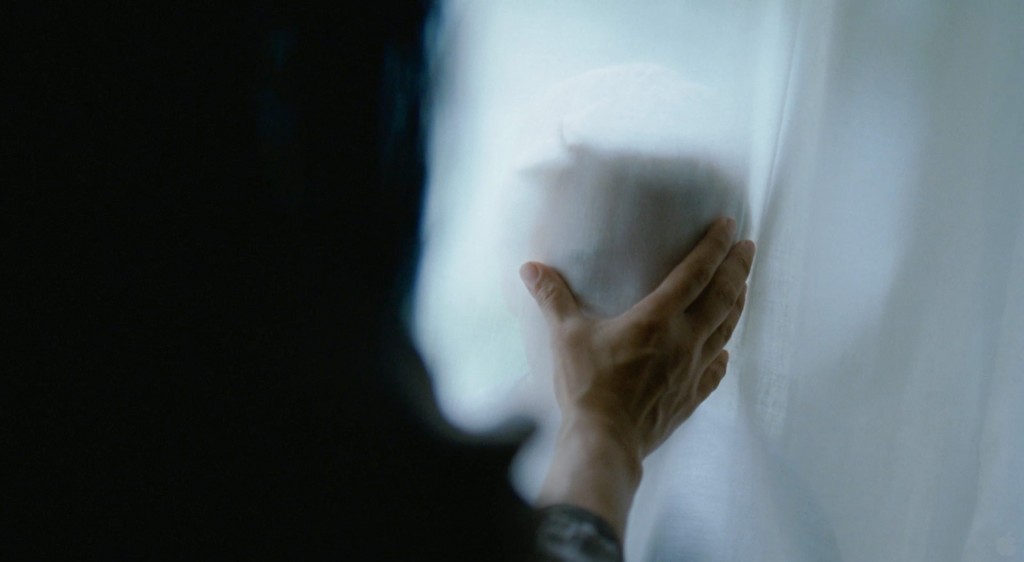

Of course I wish I could say the same about Sean Penn’s endless architectural traversals. He seems lost in this film, and there is nowhere for him to land, and here Malick, who is only really interested in showing what can’t be shown, not what the characters can see, but what they can’t see, only the emptiness, only the inexplicable origins, only the wordless (not even a whisper, but less than that, only silence), not even drapes but the wind, but he has to settle for drapes, and then he makes of them – drapes and laundry and sheets and women’s lingerie – projection surfaces across which the remnants or shadows of our lives flicker briefly into focus before dissolving back into something that is largely incomprehensible – the magic (I think) of being here right now. All this immensity right here, in this moment. And if you are truly committed to this vision, as I think he is, then you are probably going to sacrifice the whole for its parts, knowing that much of your own efforts are 3/4 blind.

I realize as I re-read this that I started a sentence and never finished it. Maybe two or three sentences. Something about Sean Penn. The ending at the beach, oh well. This movie was never supposed to end, I think. Three years in post-production (five editors) – but it should have been thirty years. The rest of his life in other words. How do you turn three years into the rest of your life? How do you ask for all those millions of dollars when the secret you have in your heart is that this movie must never end, these moments must never stop collecting? Promise them everything, give them something. That an American should have made such an expensive too muchness of a movie, vulgar in its religiosity is perhaps not entirely surprising. What’s surprising is that the bankers let him do it, and that so much of his singularity make it onto the screen at all.