Arna’s Children: A Tender Brute of a Movie

After the movie (but also the chance encounter, the second date, the contract lunch) there is the third response, typical but rare even so, not good or bad but: it made me cry. What to say exactly about Arna’s Children (85 minutes 2003), except that it is tenderly tough, merciless in its compassion and embrace. From the opening frames it is clear that these are necessary pictures, this is what the news would look like if it were the province of makers instead of corporations. No, that’s too easy, though Thierry Gravel’s philosophically intimate speech during the Leipzig Documentary Festival’s opening proceedings calling for television auteurs (isn’t that like saying ‘fat thin people?’) still rings through.

How to make a picture of this lost Palestinian state, from which we have seen already too much? Who hasn’t weighed the evidence of the camera crews, the professional lookers, the ones who are paid to watch what we can’t. Or is it worse than that? Are their eyes guided by conglomerate media ownership which, let’s be clear, is no Jewish cabal, but continues to support Israel’s illegal occupation because it is part of the consensus of empire. Yes, this is what these too many pictures have shown us: the view from above. The aerial shot, the weightless ascent of a crane, and the public building dramatically floodlit at night providing on-location backdrops, these are inventions for the ruling class. So we return to the occupied territories in Arna’s Children as if for the first time, our feet on the ground, without official statements tailored for export. Instead, the daily life of the siege, which we are guided through, every inferno its Virgil, by Arna, the indomitable Jew, the Israeli who spends most of her hours on the wrong side of the dividing line, protesting the invisible brutalities of state and their simultaneous recoding.

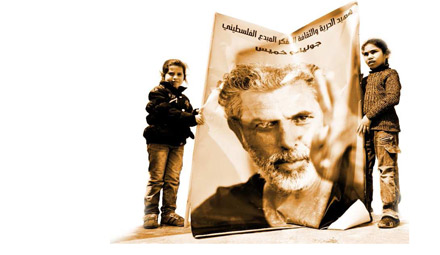

She builds a modest theatre for Palestinian children in Jenin, and asks her son Juliano Mer Khamis, the one who will become a filmmaker despite himself (to each his conversion) to teach them how to stage their own stories. Refuge, respite, representation.

They’re building it here? Here?

The other side, the enemy, are terrorists. How can we forget: as late as 1988 the US State Department still named the African National Congress one of the “more notorious terrorist groups.” Mandela was a prisoner then, exactly where he belonged. Only popular pressure (the grind of marches and meetings, pamphlets and speeches) changed all that, just as this film hopes to offer its modest, moving proposal towards a clearer understanding of a Palestinian state. But this is an intimate politics, sure Arna makes a speech or two, she leads her charge, her students, towards expression of their own (first the tears, then the rage. Never: I can’t anymore, it’s too much. But always: what now?) She lives this struggle at each tick of the clock, saying hello is also a political act. One morning one of her regulars doesn’t show and the next day Arna asks why. “It was the Israeli soldiers,” he says, they destroyed a home in his block, and his house fell into ruins as well. There is a picture of the disconsolate boy sitting in the rubble of what had been home only that morning, and there is no need for explanatory voice-overs to tell us that events like this happen only in warzones, or that this collateral damage is too commonplace to rate a place on the CNN ticker. Without oil or guns to protect them, these actions are strictly off the record.

Arna’s son returns years later, a step slower and a little greyer than before, but everywhere he turns in these ruined streets (streets is too kind a word) “Arna’s son” is the skeleton key opening faces around him. For one aged woman, clutching her shawl, memories of Arna are her only happy ones. He has come back to speak to the young boys we saw in the film’s opening half, homecoming in a place that refuses even the people who live here every day. But it’s difficult. After the hug and smile and come in, come in, there is an awkward pause. Has too much time passed? But no, it turns out that Ashraf died during a street fight, while Alla now leads a semi-military group. The boys have grown up. The director wonders: what are they doing now, and why? But what else? Raised in rubble, with the prospect of a bad situation growing worse, and all those funerals. We are taken behind the scenes, where they snipe at Israeli patrols, set bombs and trip wires, engaged in a one-soldier-at-a-time guerilla war.

Yussef is a suicide bomber.

When I read about it in the newspaper I can’t understand. The photo tells you nothing, always the damaged remains of a cafe or bus and inserted in a frame of its own, superimposed, a family snap of the terrorist/freedom fighter. But here, in this movie at last, of course, what else is there? Faced with the naked exercise of Israeli power, condemned again and again by the United Nations, and a fleet of human rights organizations who offer judgments without aid, what else?

At least, this movie. This bearing witness when so many have gone before and looked the other way. If you can tear your eyes from the White House, the Knesset, the Arafat ramblings, this is a life’s story and a nation’s. Mother would you, could you? Told through, lived through, shown through and through.

Originally published in: Dok Revue, a newspaper published by Jihlava International Documentary Festival, 2004.