We Were the Underground: an interview with Wyndham Wise (September 12, 2013)

Mike: Can you tell me about the Toronto Filmmaker’s Co-op?

Wyndham: The Toronto Filmmaker’s Co-op began at Rochdale as a collection of anarchists and hippies. I was there. Eventually it was taken over by more industry-style filmmaking. In the end it turned out that Bill Boyle, who was running the Co-op, was sifting the money off for his own personal projects. It was absolute corruption. I was there at the meeting at 67 Portland when we had to close it down because it was bankrupt. I wrote about this in Up From the Underground, published in TIFF’s Toronto on Film (2009).

Mike: What about the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre?

Wyndham: The Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre was formed by Robert Fothergill, David Cronenberg, Lorne Michaels and Jim Paxton. Its origins came out of the McMaster University Film Board, which was run at the time by Peter Rowe. CFMDC was formed because the Cinecity Theatre (formed in 1966, located at Yonge and Charles) wanted to bring up the Warhol group from New York. They couldn’t do it because no one had the cred to get hold of Jonas Mekas. It seemed too commercial for him. But they found a way. Those three days and nights in the summer of 1967 were the beginning of avant-garde film screenings in Toronto. It was a big deal. Mekas came, the Warhol films arrived, and it all became part of my DNA. Cronenberg wrote about this in his book Cronenberg on Cronenberg. He showed his student film Transfer (1966). The event was dismissed by mainstream critics as a bunch of hippies smoking dope and tripping on acid, which is exactly what it was. A lot of people came. Before this event, screenings took place in the Gerrard Street Village (Gerrard Street between Bay and Elizabeth, the area hosted the Village Bookstore, the earliest incarnation of the Isaacs Gallery, and the Jack Pollock Gallery) and the Avrom Isaacs Gallery. The Gallery represented Michael Snow, and that’s where his avant-jazz band CCMC began, and that’s where Mike showed his films. It was a high end, artistic class who decided to hold screenings at Cinecity to open this work up to a wider audience. All of that grew out of the underground movement as personified by the Factory in New York.

Mike: What are the traits of the underground movement?

Wyndham: A disrespect for authority. A willingness to push the boundaries and to bring graphic sex into the cinema. Kenneth Anger was an important figure. It was about pushing film and video as far as they could go. In the lobby during the festival there was video playing, and that was brand new for us. The French New Wave’s deconstruction of cinema showed us how to tell stories with beginnings, middles and ends but not necessarily in that order. It was all part of a community vibe and at the centre was Snow and Wieland, they were the major stars. It can only be described as a downtown elite. The primal scene of the underground was Warhol’s Factory, that was point zero, the centre of it. A little of it came up to Toronto via people like Mike and Joyce because they’d been in New York. This whole notion that Toronto could be New York has been around as long as I can remember. You’d go to a party and someone would say, “Toronto’s so boring, but in New York…” They probably still say it. It’s this wannabe attitude that I never bought into. I was twenty years old. It was all new to me, like visiting a candy store. I was having a good time, getting laid and doing plenty of acid. It’s a part of my life that doesn’t exist anymore. You came late. You came late to the party. It can’t be repeated, it was just a moment in time.

The Underground exploded between 1964-1971. Cronenberg emerged unscathed and went into the mainstream, but he wasn’t accepted for a long time. The work that was applauded was Michael Snow’s. I remember seeing Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) when it was shown by Ian Birnie at the Art Gallery of Ontario. I was blown away, though not because it was a good film. The performances were poor and the horror was a piece of turd that got into people and turned them crazy. But I saw someone with a vision. He was smarter than the material, he had a sense of what he was doing. A lot of people I was involved with in the avant-garde scene, I’m not so sure they understood what they were doing. Apart from causing trouble. I think the avant-garde cannot exist without the middle class. Who would oppose them? The avant-garde is always in opposition. If you get a house and a mortgage, you have something to protect. The avant-garde was always attacking those values. Live for the moment. Live for art. Don’t live to pay your rent. Don’t live to achieve any sort of commercial success.

So what do you want? Do you want nostalgia or the truth? The beginning is 1967 on St. George Street when I met Richard Schoichet. It was the first or second day of University College at the University of Toronto. All the colleges were lined up by religion – so if you weren’t High Anglican, United or Catholic, you went to UC. Mostly there were Jews and hippies. I was studying political science and history, but I’d always been interested in theatre. There were two theatres at UC: the Glen Morris and UC Playhouse. At the Glen Morris I helped put on a Czech play called The Good Soldier Švejk (1923). It was directed by a European guy who had problems adjusting and wound up committing suicide. I was doing tech stuff because that’s what I’d learned in high school, but the play was difficult to mount in such a small space. It collapsed under its own ambitions.

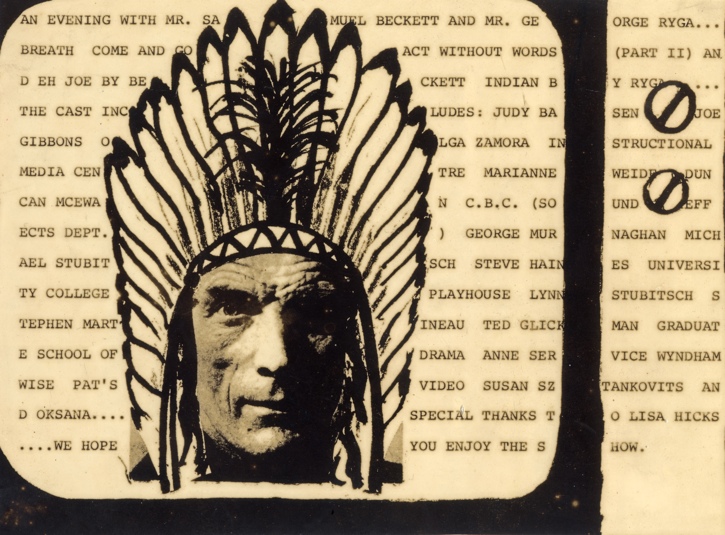

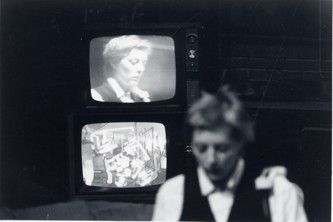

Come and Go, Act Without Words and Eh, Joe? by Samuel Beckett and Indian by George Ryga

directed by Wyndham Wise at the UC Playhouse, 1974

I was in a heavy-duty relationship with a girl I was engaged to marry. We became on campus darlings through an odd set of circumstances. Our picture had been taken at the frosh, caught in an embrace that wound up on the front cover of The Varsity newspaper. We were the romantic couple of the college before we broke up. The Band had just released its first album “Music from Big Pink,” and their song The Weight ran through our whole time together. When I came back to school in 1968 I was married but it was a disaster, we broke up two months after consummation, or lack of consummation. She took off to see the world.

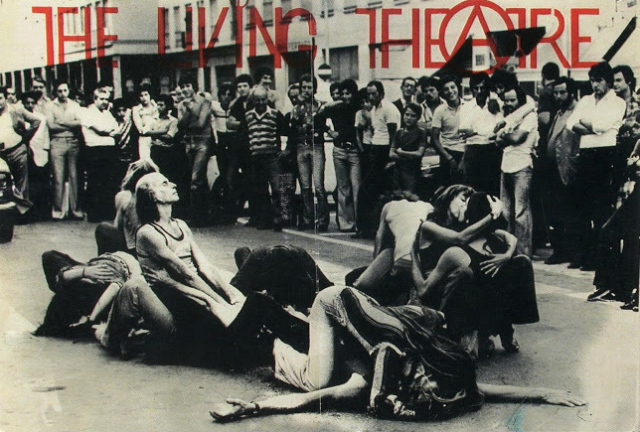

Meanwhile Richard and I had started to work together, we were ambitious to do things. Cronenberg had made his student films, we knew of his existence. We knew there was something out there, but didn’t know what it was. In 1969 I quit university and tramped around Europe and Israel for two years. In those days you just picked up your backpack and left. When I got back to Toronto in 1971, I decided that what I wanted to do was film and theatre so I started in again at University College. Stephen Martineau taught there. He was a Brit with a deep knowledge of contemporary theatre. Julian Beck and Julian Malina’s The Living Theatre had come into town, the world’s oldest experimental theatre group. We were working with the Poor Theatre ideas of Jerzy Grotowski. While Hair was packaged as a commercial venture, we were doing it underground. It was assault theatre that came out of Genet and Artaud. We did spontaneous work around campus.

In the eighties they came up with this term: bromance. Do you remember that? Guys liking guys only they weren’t gay. It’s a stupid concept but anyways, Richard and I had a really tight relationship. When I met him his parents had just gifted him a brand new Mustang for graduating high school. Top down, stoned out of our minds, driving around in a Mustang… they were good days.

I shot my first film in super 8 and called it Mushrooms (2 minutes 1971). It featured a young lady – a friend – peeling mushrooms in my kitchen. It was made at 111 Lowther Avenue, right on the corner of Spadina. The University of Toronto had film equipment that Cronenberg had used for some of his early features, and ten years later Atom Egoyan used the same gear. Somewhere between the two was me. (laughs) The film was shown in class and I was given an A, but there wasn’t anywhere else to take it. Super 8 exhibition wasn’t even a gleam in Ross McLaren’s eyes, and CEAC didn’t exist. My professor was Joe Medjuk, who later went down to Hollywood with Ivan Reitman. He became the associate producer on Ghostbusters (1984). Joe was the one who wound me up about film.

In my fourth year I shot an 8mm film called Red (5 minutes, 1973) for a class project. I filmed a red piece of bristle board, with titles announcing parts one and two. Some of the students in the class were going to string me up. I pissed them off so much. A couple of guys in the class, who wanted to be filmmakers, thought I was having a joke on them. They really tore into me. It’s hard to be on the outside when you’ve got no money. You become much more survivalist, and I found it hard to survive in that kind of world.

I shot a 16mm film I called Garbage (30 minutes, 1974) in the summer of 1974. I had worked two summers for the City of Toronto Works Department to pay my way, so I went to the city and asked if I could follow a garbage truck around. They agreed, and I decided to shoot the film in a single, half-hour shot. We were on top of a car on Palmerston Avenue, north of Bloor, but because it was such a large reel, the camera magazine jammed and I had to fix it in a hurry. I submitted it to the student film festival in Montreal, which later grew into the Montreal World Fest. They sent back a certificate acknowledging that they’d screened the work, so that was pretty neat. Garbage had its first public screening at A Space Gallery in 1974. Trick Brenner and Linda Griffiths were an item and friends. They must have been there because shortly after the screening I hired Linda for what would become her first production, a play that Richard and I produced called Shop-Talk.

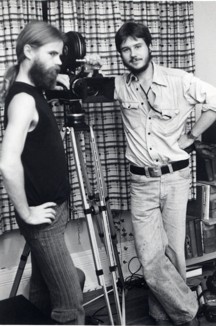

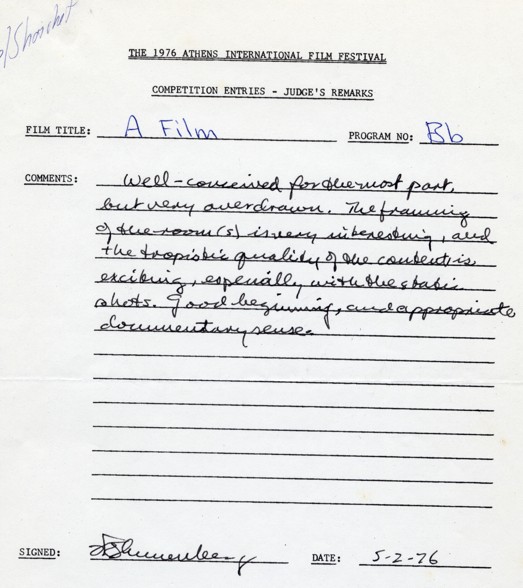

Around the same time, I ran into Noel Harding, who was showing work at the Art Gallery of Ontario, we got along well together. He hired me to do some freelance film work because I could get hold of equipment from the university. I shot another film with Richard called A Film (20 minutes 1975) which later became known as A Sound Film. I got that title from Michael Snow who was working on a double-screen installation called Two Sides to Every Story (1974). We were hanging out one day when he gave me the title. It offered a series of one-shot scenes I’d constructed, influenced by Godard’s use of master shots in Weekend (1967). I’d written a script for actors who weren’t really acting. I was living on Huron, just south of College Street with my second wife, Ann Service, who was a part-time teacher and a poet. Peter Wronski shot it in the ground floor flat we were renting for $400 a month. It had doors in the centre room that could be opened and closed, so you could find unexpected depths. It wasn’t a very good film, but it was the first I shot in 16 mm.

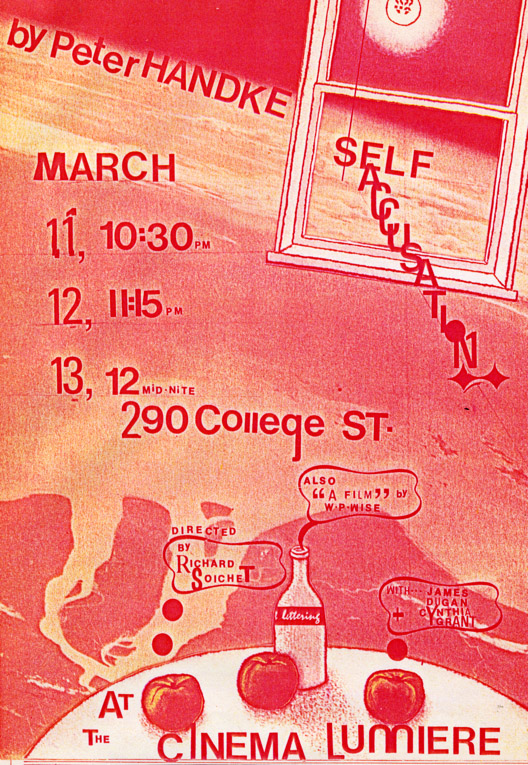

In 1975 Richard set up a three-night run at Cinema Lumiere of a Peter Handke play; a two hander called Self Accusation (1966). Here’s a bit from the Handke play to give you an idea: “I walked purposelessly. I walked purposefully. I walked on paths. I walked on paths on which it was prohibited to walk. I failed to walk on paths when it was imperative to do so. I walked on paths on which it was sinful to walk purposelessly.” Each night I showed A Sound Film before the play.

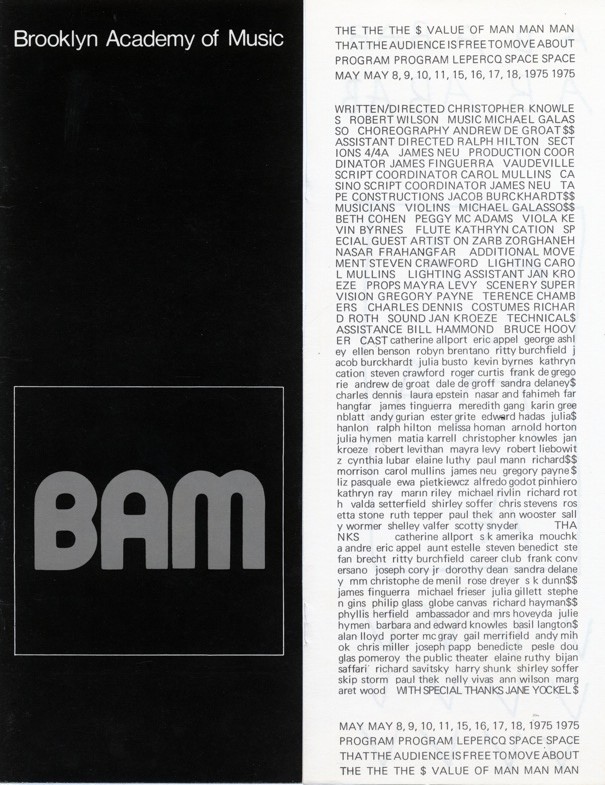

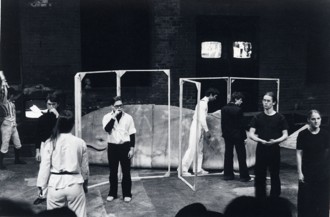

In 1976 Richard and I did Shop-Talk, a multi-media play at the Toronto Free Theatre. It was Linda Griffiths’s first production, and I shot the video that appeared on monitors. Richard and I had seen The $ Value of Man (1975) down at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, a brilliant early Robert Wilson piece. He constructed it using a series of open spaces with cast members performing simple activities which the audience was invited to join. I’d never seen anything like it. I was the first person on the floor and everyone else followed.

New York was dirty and full of pornography, but it had a vibrant avant-garde scene. We saw one play after another but the one that really knocked me out was the Robert Wilson. We tried to make our own version with a whale. I don’t know why Richard wanted a whale, but the stage manager built one for him. Richard had these big dreams and there were a couple of people including myself, who made it happen. He had a unique way of seeing the world, a very bright guy.

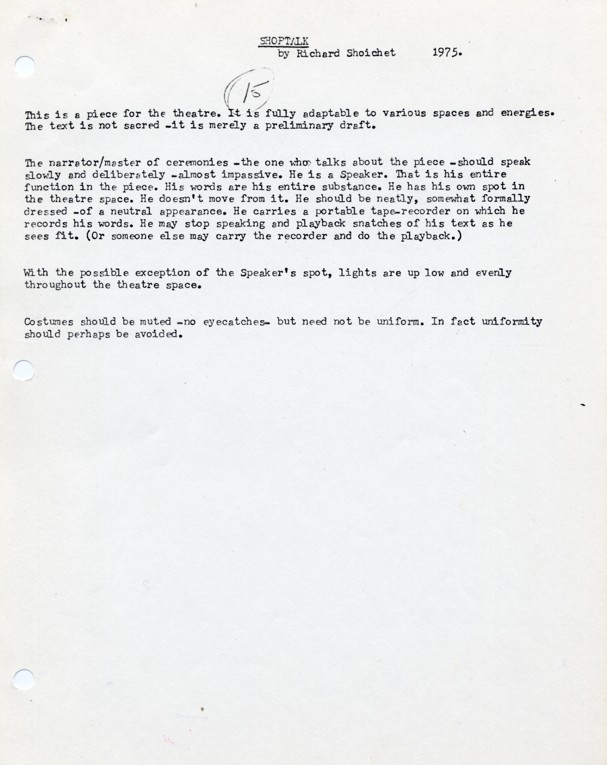

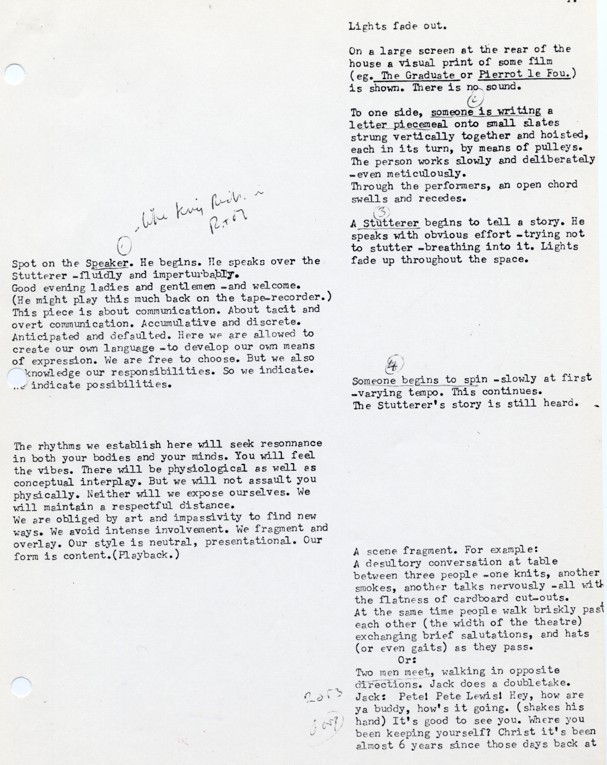

Mike: What was Shop-Talk about?

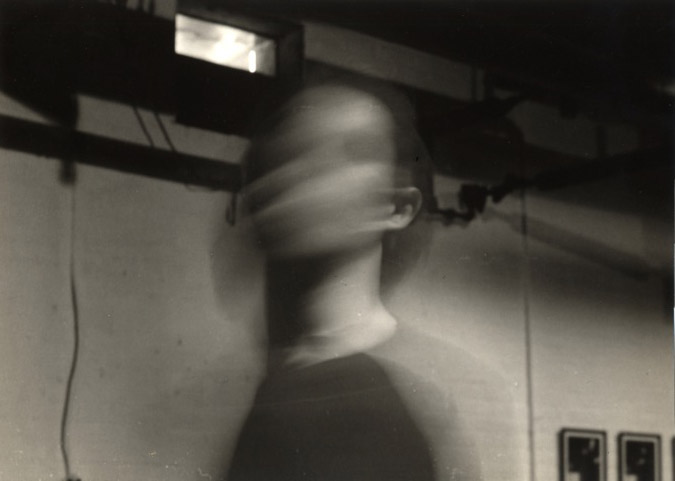

Wyndham: Quite frankly, I don’t know what it was about. It had a dozen performers in a space performing certain activities. One of them was Chris Radigan spinning. We’d seen that in the Wilson piece. Chris had an ability like a Turkish whirling dervish to spin for long periods. You can’t spin on the same spot for half an hour because you’d fall over after a few minutes but Chris had the knack.

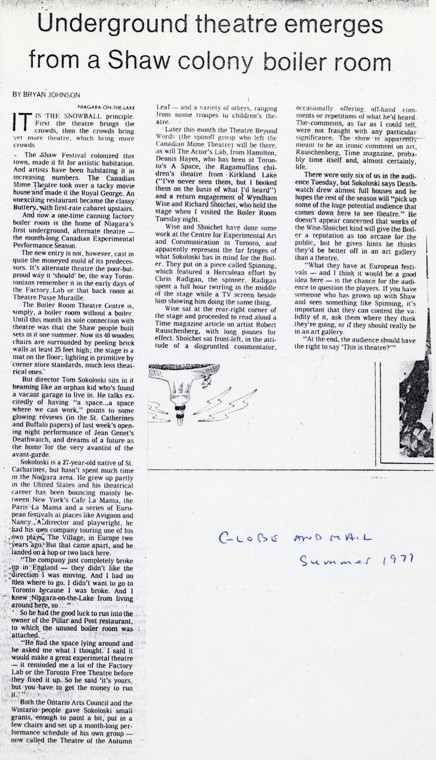

The play was constructed as a series of frames, but I don’t think it was successful. I don’t think it was anything more than a couple of guys trying to reproduce what they saw in New York. Richard wouldn’t say it that way, but that’s how I felt. We received very negative feedback. The most famous incident was with Des McAnuff, who went on to become the director of the Stratford Festival before going to Broadway, where he put on Tommy (1993) and later The Jersey Boys (2005). He was so pissed off at us for what we tying to do that he came just to disrupt it. When we invited the audience to participate (like the Wilson play), he came onstage and began spraying the performers with whipping cream. It was funny, but the actors didn’t know what to do, so I grabbed him, carried him to the entrance and threw him out. I was in tears. Years later Richard told me it was Des. His ambition was to use whatever he could do in Toronto to springboard into the US. He wasn’t a believer in this sort of stuff. He wanted to go big time. Paul Thompson at Theatre Passe Muraille, who had been a supporter of Des, was never into that. He was into local communities. He was willing to go out on a limb with whatever you came in with. After Shop-Talk we went to Paul and said we’ve done this piece, now we’d like to take the next step. He got behind us. He even tried to explain what he thought we were doing. Part of the reason I got out of this whole conceptual performance scene was because I didn’t have a grasp on it. I couldn’t get it into my practical head. I thought it was innovative. I could see people were interested, but it didn’t do anything for me and ultimately Richard started using me as a stage manager. And I sure as hell wasn’t going to be the stage manager, so our friendship came to an end.

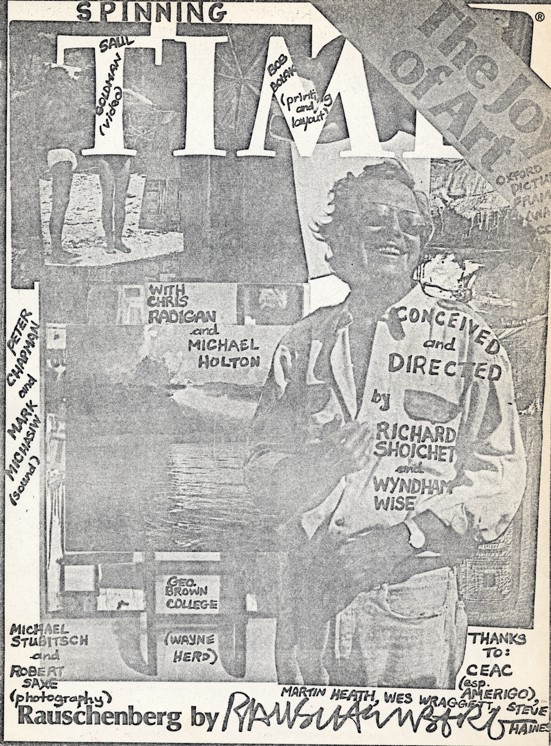

For our next piece, Spinning, we took Chris Radigan out of Shop-Talk and had him perform his piece solo. We brought him into the Glen Morris Theatre. I got equipment from the University of Toronto and shot him spinning in circles from different angles. I circled him. I shot from above and below, and constructed his simple movements into a 15-minute film called Spinning (1974). We were aware of CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication), which owned a four-story warehouse building at 15 Duncan Street. It was another venue where we could stage our work. Spinning ran four nights, and featured Chris spinning for 45 minutes. There were a couple of monitors that ran a looped version of the film with some augmented sound. It wasn’t a particularly stylish show. We got an audience of two people and a dog.

I had been to CEAC a few times, for instance to see Running in O and R by Peter Dudar and Lily Eng (1976). It was like watching a game of cricket, where there are two batters and if one gets a hit the two trade places. Peter and Lily were running back and forth from one side of the room to the other. There might have been 20 people in the audience. This stuff was really fringe. What’s interesting is that today people have made these past events very precious to enhance their egos or to give people the impression that something important was going on. However, the really vital scene in Toronto was not the underground (and we were the underground) but theatre. Theatre exploded in Toronto during the seventies. Canadians were starting to write plays and new theatres sprang up like Passe Muraille, Factory Lab and Toronto Free Theatre.

CEAC was dirty and empty. They had a big space, the entire fourth floor of a warehouse building, and I think Amerigo lived with his boyfriend in the back. A lot of it was gay and I’m very straight. I’ve got nothing against gay sexuality, but there was something about the place that put me on edge. I didn’t feel comfortable, maybe because sometimes there were naked men walking around. I remember that. There was a naked guy walking to the bathroom. It was an extension of the hippie commune where everyone iss supposed to be cool, and all types behavior were accepted. There were a lot of people doing odd, experimental stuff, and Richard and I were on the fringes of it. I wasn’t one of the major players like Michael Snow or Amerigo at CEAC or whoever was running A Space at the time.

Mike: Did others feel on edge at CEAC? Did it feel like a small scene of insiders?

Wyndham: Very much. It was a closed scene. I don’t know what other people’s reactions were, but this wasn’t for a middle class audience. You ain’t gonna get blue rinse and shirt and tie. You’re going to get people like myself, or people in the alternative scene. Occasionally there were more upscale events like Philip Glass’s concert of Einstein on the Beach (1975) that drew fifty or sixty people. That was the largest crowd I’d ever seen there.

My interest was in film, so if I was going out for entertainment, I would try to see films. Plus I was poor, still am, and going out meant spending money, even if it was five bucks, which at that time could buy food for a week. I was always very conscious of the fact that I was an outsider and dead broke. I had to drive cab back in the quote real world. So when I got into a place like CEAC it felt very closed and precious, I’m sure they thought they were doing something radical that was going to change the world.

Spinning ran for four nights in February 1976. CEAC had arranged a performance night at P.S.1, a gallery in New York, and invited us to join them. They hired a mini-bus, and it was a bit of work to pack the monitors and bring Chris, Richard and I, along with performance artists like Amerigo, Ron Gillespie and Diane Boadway. I don’t remember if there was anyone else. We went down in March, a month after the CEAC shows. We nearly died because there was a snowstorm and the van skidded on the highway going down to Buffalo. I’d been through the US Customs a number of times and understood if you have long hair and a beard you’re going to get into trouble. So the rule is: ‘Yes sir. No sir. May I lick your ass sir?’ But when the customs guard asked why we were going to New York, Diane answered, “Well, we’re artists.” “What’s an artist?” the guard asked. “We’re intellectual artists,” she said. I almost shit my pants. I can’t believe the guard didn’t throw us out. Speaking of being a closed knit group. Here were a bunch of idiots who couldn’t deal with the real world. They couldn’t even pretend to be straight in front of a government official. Customs kept us for an hour-and-a-half while they tore the van apart and finally let us through.

Mike: Can you describe the CEAC performance evening at P.S.1?

Wyndham: We had an audience of two and a dog. Do you know where that phrase comes from? I attended a screening at the Art Gallery of Ontario by Stan Brakhage who said that his usual audience was two people and a dog. It’s a funny line! I’ve been to screenings of Canadian screenings that had one person in the audience. There might have been a dozen people show up in New York. I can’t remember what else played except for Spinning. You’re the first person I’ve talked to about this in decades. For a long time I’ve put all this aside. I had a break with Richard, and we went different ways, and all this went into the back drawer, and wasn’t part of my memory bank. I didn’t feel comfortable there.

After Spinning, Richard and I did one more production called Con/Notes. It included Angie Gei, Randy Campbell, Jennifer Fischer, Howie Cooper, Sarah Hickling and Ken Williams. It ran at CEAC for a week in the summer of 1977. That was our last gasp. Richard had written it while I helped produce and threw in some Hitchcock bits. It was mostly a series of vignettes. There was a bedroom scene, and a beach scene that we brought in sand for. Amerigo had cats who decided to use the sand as a litter box and that became problematic. Angie, dear Angie who had to lie on the sand, told us: this smells like piss. So I had to clean out the litter. It was part of that dirty thing. You can’t control your cats, you don’t have a litter box so the cats just shit anywhere they want. That really put me off.

Mike: CEAC did European tours, and were very well connected internationally. Were you wondering how you might become part of the circuit?

Wyndham: No, I was thinking about how to get out of this scene. How do I get away from people who think they’re intellectual artists? I’m not going to hang around with people like that. After PS1 I didn’t want to have anything more to do with Amerigo. His politics didn’t turn me off, I just didn’t like him. I thought he was dirty and I’ve got this thing about dirty. He had dirty fingernails. Where do he stick those fingers? Maybe it’s my British upbringing, maybe I was too middle class for all this stuff. So when the shit came down with CEAC because they had come out in support of the Red Brigades kidnapping of Italian premiere Aldo Moro in 1978, which the Toronto Sun put on their front cover, that really turned people off. I was just amused.

Mike: Did you show your movies at the annual Toronto Super 8 Film Festival (1976-1983)?

Wyndham: The first Super 8 Festival was held at the Ontario College of Art. Ross McLaren and I were standing in the entrance to the auditorium when I asked him why he turned down my films. He told me they weren’t good enough. I couldn’t believe it, who did he think he was? I’d been making films for years already, now this snot-nosed kid from art college was saying no? That’s when things turned sour for me. All the efforts to establish myself had come to nothing. The performance down at P.S.1 was a bit of a disaster, the audience was small, and the line about intellectual artists really put me off. Ross put me off as well. The avant-garde was a scene run by privileged kids who could make privileged art with their daddy’s money and become intellectual artists. I didn’t have the money to spend another couple of years trying to make a go of it. That was one of the turning points. After that scene with Ross I really wondered: what am I doing this for? I’d already made three super 8 films a couple of 16-mm films. So why can’t I get into a small local film fest dedicated to Super 8? Why do I even have to deal with these people? I like smart people like Michael Snow or Richard, but I didn’t have respect for people like Ross. Actually, I was more interested in doing Alfred Hitchcock than Robert Wilson. I wanted to make the great Canadian film. I wasn’t interested in experimental theatre for two people and a dog, so when I was almost 30 I cut my hair and beard and became a straight-looking kid again. I had been a fashion model when I was a teenager and decided to get back into the business.

Mike: Did you ever go to Freud Signs, the screening series ran by Keith Lock and David Anderson?

Wyndham: No, but I knew Keith through Michael Snow. Michael had come to my wedding to Jane Perdue. He was a friend of Jane’s. As you can tell, I was more interested in women than I was in experimental theatre. I knew about the Funnel and visited their King Street location for screenings and openings, but because it was Ross’s outfit, I had little interest. But being a curious researcher, and as someone who paid attention to what was going on, I went despite having no interest. I thought Ross was a hustler. He was hustling grants and got enough money to get the theatre rolling. By the time they got going I had stepped aside from all that avant-garde stuff. I went into what people at the Funnel would consider “straight” filmmaking, the business of making films, as opposed to creating work no one saw. I had more success with that than the avant-garde. I was getting more attention because I was a good-looking and had brains in my head. Those advantages weren’t getting me anywhere in the avant-garde.

I was married to Jane for twelve years and we had two kids together. We met during a Noel Harding performance down at Harbourfront. We got along famously for about four years before the marriage started to fall apart. Jane worked as an assistant to Peggy Gale who was running A Space when it was at 299 Queen Street West. Michael had a studio there too. Noel Harding was around and he eventually married the photographer Barbara Astman. We were all close friends.

After my break with Richard, I formed my own company. I was producing films and writing scripts until all that fell apart near the end of 1984. Jane and I were living at Queen and Euclid, a large flat above a hardware store. Jane was friends with Tom Dean and Elizabeth Chitty and many others. We were Queen Street West. Jane has a wonderful personality and can walk into any situation and be friendly, unlike me, when I step into a new encounter I’m usually defensive. She always had a smile on her face, while I’m the one standing in the back of room, always on the outside looking in.

Between 1980 and 1989, Queen Street bloomed and all the artists arrived. Even though I had stepped aside from the scene, I remained connected through Jane. Every week we went to openings and receptions. Jane was good buddies with General Idea, and we used to go to their house parties. Three really bright guys. My personal bane – and advantage – is that I look a lot younger than I am. When I was 40 I looked like I was 30 or even younger. But I’d already been around for 20 years, and that became a bit of a problem. There were a lot of people I couldn’t respect. I remember Judith Doyle coming into A Space extolling the virtues of neg cutting as if she’d just personally discovered cinema. Oh Judith, you’re so sweet.

After my filmmaking/producing career came to an end, I drove cab full time for two years to pay off my debts and decided to go back to York University in its graduate film program, and from there I was hired as the last Toronto reporter for Cinema Canada magazine. Part of my job was to write monthly news briefs. One of the items I came across noted the Funnel closing. I wrote it up and after it was published Ross McLaren came into the office in the basement of 67 Portland and tried to rip me. He was pissed because I’d got it right. He wanted me to retract the notice, How dare I? I said, ‘Ross, let’s talk about the equipment. Where’s the equipment?’ The Funnel’s equipment was in his basement. You know how I know that? Because he told me so. I’ve seen stories on the Web about the Funnel’s equipment disappearing. Well, it didn’t disappear. When the grants ran out he stripped the place and walked away with everything. I don’t like dealing with people like that. I’ve met a lot of scum in the film business, but it was never so personal. I had a producer once try to rip me off for a script I wrote, but with Ross it was never so personal.

Mike: After editing Cinema Canada you started an influential magazine about Canadian cinema called Take One.

Wyndham:

I was teaching part-time at Sheridan College with $2500 in my pocket and thought this is it. I couldn’t do it with my films. I couldn’t make it in the commercial world. I had one more roll of the dice, and I took it. After the first issue came out, I couldn’t believe it. Suddenly I was being invited to parties. Suddenly people were saying: hey, check out Take One. Now it’s my turn to tell the world about what I think about Cronenberg and Michael Snow etc,, and I’m going to put it in my own magazine. I got the first two issues out on my own nickel, and went to the Ontario Arts Council and said the third issue isn’t out yet, but I submitted an outline of the 44 pages and they said OK. I got the grant.

What I’m proud of is all the stuff I’ve done since the launch of Take One. U of T Press published Take One’s Essential Guide to Canadian Film in 2001. If you go onto the Web and search for the top Canadian film historians you will find me. People quote me and film students study my book at school like they do yours. I thought: that’s not so bad. I’ve done something. The stuff you’re interested in, the avant-garde stuff, is more ephemeral. I’m glad you’re doing this project and I hope you get it right. There was a lot of crap going on in the early days; a lot of stuff that was accepted as art that was pure junk.

You’re probably not going to find another guy like me, someone who has a critical opinion of the scene. You know what I’ve discovered? Everyone wants good news stories. I edited the last issue of Independent Eye, the first issue of POV for the Film Caucus (now the Documentary Organization of Canada) and the Canadian Screenwriters Guild hired me to launch their magazine Canadian Screenwriter – all of them wanted good news stories. They were not interested in any critical edge whatsoever. The last magazine I worked for was put out by the Canadian Society of Cinematographers, which I transformed it into Canadian Cinematographer in 2009, but the people in charge exorcised anything that hinted at criticism so I got fed up and quit. This goes on throughout the business. You hear it on all the time on those TV entertainment shows. Even if someone is dying of a heroin overdose, there’s got to be a blonde announcer with a smile on her face telling us about how he’s going into rehab and this time he’s going to make it blah blah blah. It always has to be a positive, good-news story. I wonder if that’s a North American thing. Perhaps we can’t handle the truth.

FILM PRODUCTIONS

Liona Boyd in Concert, co-produced, video, 90 minutes, 1982

Liona Boyd: First Lady of the Guitar, wrote/co-produced, video, 55 minutes, 1982

Simplified Confusions, photographed/edited, 16mm (installation by Noel Harding), 1977

Victory Variations, produced/directed/photographed/edited, 16mm, 15 minutes, 1977

One Apparent Event Towards Two Transparent Moments, photographed/edited, 16 mm (installation by Noel Harding), 1977

Spinning, produced/directed/photographed/edited, 16 mm, 20 minutes, 1976

Once upon the Idea of Two, photographed/edited, 16mm (installation by Noel Harding), 1976

A Sound Film, produced/directed/wrote/photographed/edited, 16 mm, 20 minutes, 1975

Running in O and R, photographed, 16mm (installation by Peter Dudar and Lily Eng), 1975

Garbage, 16mm, 30 minutes, 1974 (student film)

Mushrooms, 8mm, 2 minutes, 1971; Come and Go, 8 mm, 10minutes, 1972; Red, 8mm, 5 minutes, 1973 (student films)

THEATRE PRODUCTIONS

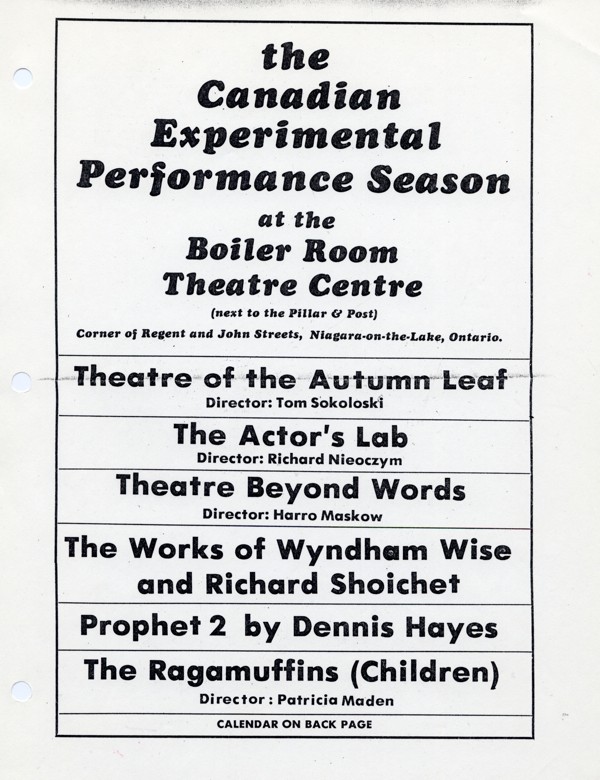

Pygmalion Has Been Cancelled, wrote & directed, one performance only at The Boiler Room Theatre Centre, Niagara-on-the-Lake, 1977

Con/Notes, written & directed with Richard Shoichet, produced by Theatre Passe Muraille and staged at CEAC, 1977

Spinning, a performance piece, produced with Richard Shoichet, presented at CEAC, Toronto, and P.S.1, New York City, 1977

Shop-Talk, written & directed with Richard Shoichet, Toronto Free Theatre, 1976

Breath, Come and Go, Act without Words Part II & Eh Joe by Samuel Beckett; Indian by Geroge Ryga, UC Playhouse, 1972 (student productions)

Linda Griffiths in Shop-Talk

Linda Griffiths in Shop-Talk