Before you die, you have to go and live in the graveyard. Never mind cremation or the scattering of last thoughts, the once annual day of the dead has become the everyday of the dead now that we have embraced our digital future. The incessant archiving, the restless doubling of everything in our world, doesn’t this reveal a terrible anxiety: that everything is vanishing? That we are living in a world that is forever dying and disappearing while we try to hold onto it with our super phones, the ones that walk us through the valley of death. Or as Yurri Herrera calls it “the saddle.”

“When she reached the top of the saddle between the two mountains it began to snow. Makina had never seen snow before and the first thing that struck her as she stopped to watch the weightless crystals raining down was that something was burning. One came to perch on her eyelids; it looked like a stack of crosses or the map of a palace, a solid and intricate marvel at any rate, and when it dissolved a few seconds later she wondered how it was that some things in the world – some countries, some people — could seem eternal when everything was actually like that miniature ice palace: one-of-a-kind, precious, fragile.” (Signs Preceding the End of the World)

Last February my friend Mike Cartmell died, it was cancer of course, if you dodge all the other bullets cancer is the last one in the chamber. You can say no to all the other boys, but cancer is the guest that is impossible to refuse. Mike talked about dying all the time (that lump in my throat, my inability to speak, difficulties with my father – are these pre-signs of cancer?), except when he was dying. I wanted to talk about the endgame, but even when he could only hold forth lying down, in a funerary hush, he was certain the cancer would fade, that he would be granted the gift of a few more years. More than anything he wanted to see his two boys, and Jazzbo most of all, the one who had spurned him, suddenly and unexpectedly. It was the gravest wound in a life of difficult feelings.

Mike was born to parents he never saw, they left him on the steps of the hospital wrapped in a blanket. I don’t know how long he spent there, but he never got over it, and the elderly couple who adopted him, and who soon changed their minds without sending him back to the agency, were unable to provide the requisite shelter. He was the smartest person I ever met, plagued by his overly large brain, by the undo expectation that whatever he did should be the best and brightest of them all. Either he was the paradigm-shifting everything, or else he was nothing. The deal he finally struck with his hectoring internal critic was that he could make things, but only if he didn’t show them to anyone. As a result, he left behind a trove of secret movies and writings, even a secret website. His son Sam is determined to let everyone in on the secret, to reveal all that his father had kept in the shadows for these many years. This is a digital moment after all, and one of the imperatives of the digital is that everything and everyone should be visible, the pixel at the edge of the picture should be as sharp and clear as the pixel in the middle — in other words, there is nothing in your life, no matter how banal, that doesn’t bear scrutiny, the surveillance managers (and how busy we are helping them with our selfies, our Facebook postings, our traceable searches via the Google machine) insist on it.

But wait: what does this have to do with found footage? Aren’t I reading a found footage magazine? What I crave most of all when I arrive here is permission. Permission to flaunt the oldest of the laws: thou shalt not steal. Here, between these covers, we have come to uphold a new law: thou must steal. As often as possible. As often as necessary. Stealing is not a crime in our post-identity world, it’s a way of swapping personas, of dissolving boundaries, of saying yes to our interbeing.

The act of stealing lies at the very heart of digital culture. We like to call it by other names now, we like to say: file sharing, or downloading, ripping, cut and pasting, seeding (via bit torrents), but it all amounts to the same thing. What used to belong to you, now belongs to me, in fact, it is me, it’s who I am. I am this collection of borrowed photographs and borrowed phrases (He was all up in my grill. You need to chillax, homes.). Even my genetics are cut and spliced from generations past, I am a copyleft machine, a living collage of hand-me-down codes, a blood and sweat found footage avatar.

One of the many amazeballs Mike dropped in my lap was that every act of mark making, of writing or painting or making movies: was a form of grieving. The mark said: someone was here, someone looked like this once, or did this once, left this impression, in this way. What Mike saw when he looked out into the city were pyramids, giant funerary monuments to bygone times and people.

Now that he’s no longer around to vomit on the table all his traces feel beyond precious. The email that he sent me six years ago, the baseball cap he left behind after an evening of too much good port. It’s weird how the slightest impression, the more sentimental the better, takes on a weight and charge because he’s left the building. If I could ring him up this aft I wouldn’t dream of revisiting his long forgotten mails but now I do it all the time, in other words, I am living in his archive, his digital graveyard. I’m not making a found footage film, I’m busy living a found footage afterbirth. It’s the only way I have of talking to the dead, of carrying on a conversation that we had jogged between us for decades, and that can only be held up by his remains. It’s a way of keeping him alive. When I remember Mike, whenever any of his pals recall him, for that instant at least, he is no longer dead. I think this is a keynote for found footage makers. We are all of us working in a digital graveyard, and when we perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, when we take some long forgotten bit of footage and fold it back into some present day concern, we are bringing it back to life.

Let’s bring back a few of Mike’s excellent words, here he is imagining what life would be like in a not too distant future. “In the next century, everyone will get cameras which will be the size of your hand with great resolution and digital sound. Maybe you’ll have two or three, one in each hand with one on the top of your head looking backwards, who knows? The point is, there’ll be this ongoing recording. Then twenty years later everyone will die. That’s important. They’ll die and somebody will see this material that they’ve never seen before. Cleaning up. Going through Dad’s shirts. In some cases it’ll be a lot of Funniest Home Video stuff. But sooner or later they’ll come across a psychotic family, a family in disunity and disarray, a family that is the family of the future, a family that doesn’t resemble the family as we know it ideologically. Some kid will get this stuff, and this won’t be a kid plagued by the literary. It’ll be a kid who lives in a different culture, a kid who is totally digital, and this kid will be someone who needs to make art, and this will be the material. What do you usually find in the history of sons and daughters going to the attic? Letters. What could be more literal than letters? But now it’s going to be images and sounds, and this kid is going to make something out of all that. An unbelievable work of mourning, which is what all art is. The reason we do it — grief.

Because we’re always mourning, we always want to make sure that we will be remembered. Making work helps because it remains — archival permanence and all that. It’s a deeply unconscious part of it, individually and culturally. There’s the knowledge we’re going to die. There’s also the threat of total annihilation that makes our culture different than any culture, ever. There may not be anybody left, and that’s a new idea. We must be a culture that’s radically grieving to want to set up the potential to completely annihilate ourselves so that there won’t be anyone to mourn. That’s the radical Other of civilization — nobody to mourn — inasmuch as civilization exists so that those who die will be mourned. That’s why culture is organized. Every moment of culture is the setting in place of memorials and monuments.”

Of course he couldn’t have predicted the cellular telephone and its mania for reproduction. And beyond that: the personal computer in its many forms, which has at its heart the archive. We are all busy creating archives of emails, photographs, Youtube faves, Google search clickathons. And when we die we are going to leave that behind, perhaps in the hope that others will spend time in our digital graveyards. Perhaps that’s what we’re doing with our computers, we’re building a digital graveyard that our friends, and maybe even people we’ve never met, will spend their lives inside. We used to have a different name for this graveyard, we called it: a library. What did my former friend Janieta say? All of my best friends are books. Today some of my best friends are computers, or at least archives, or at least found footage.

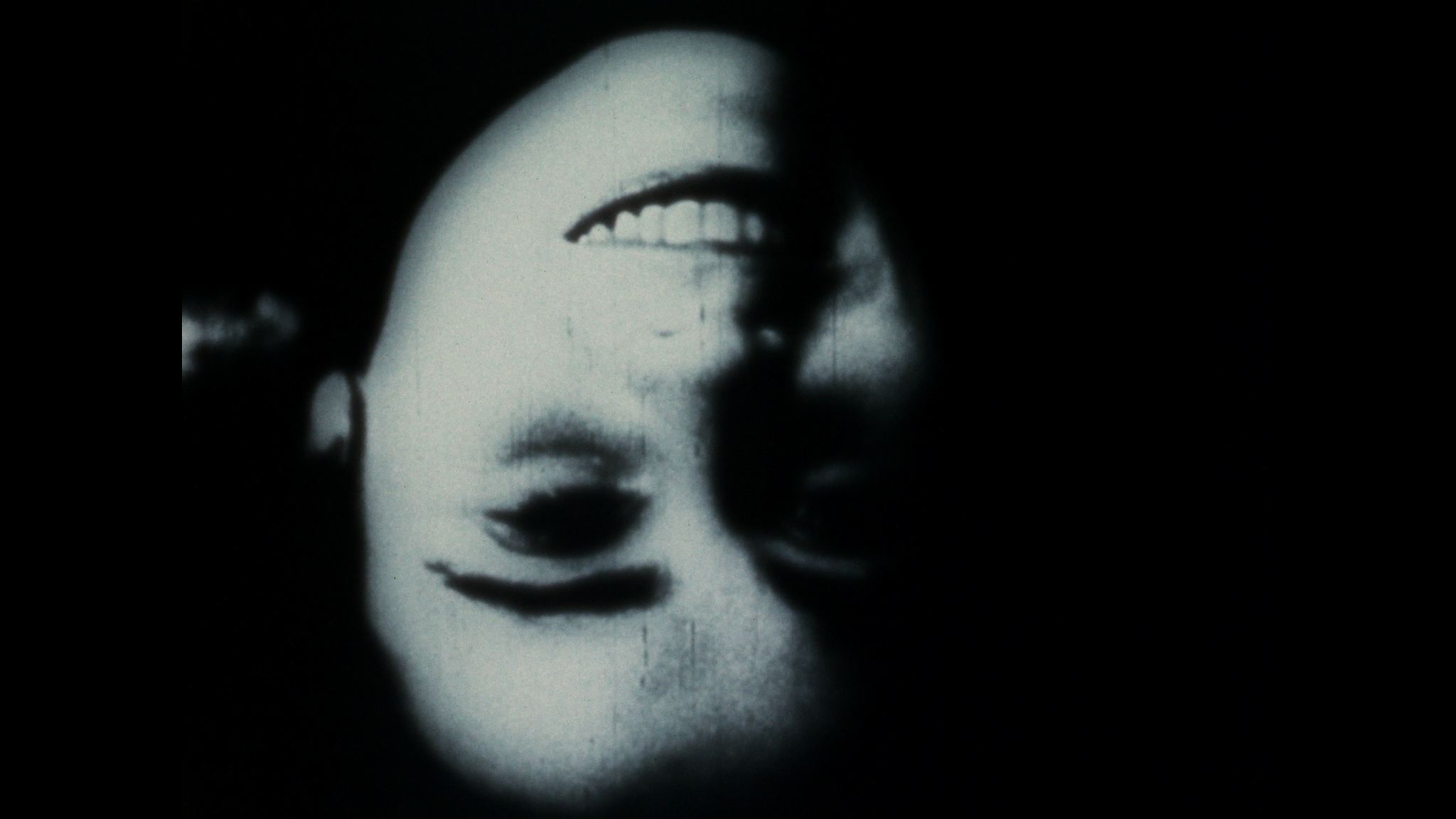

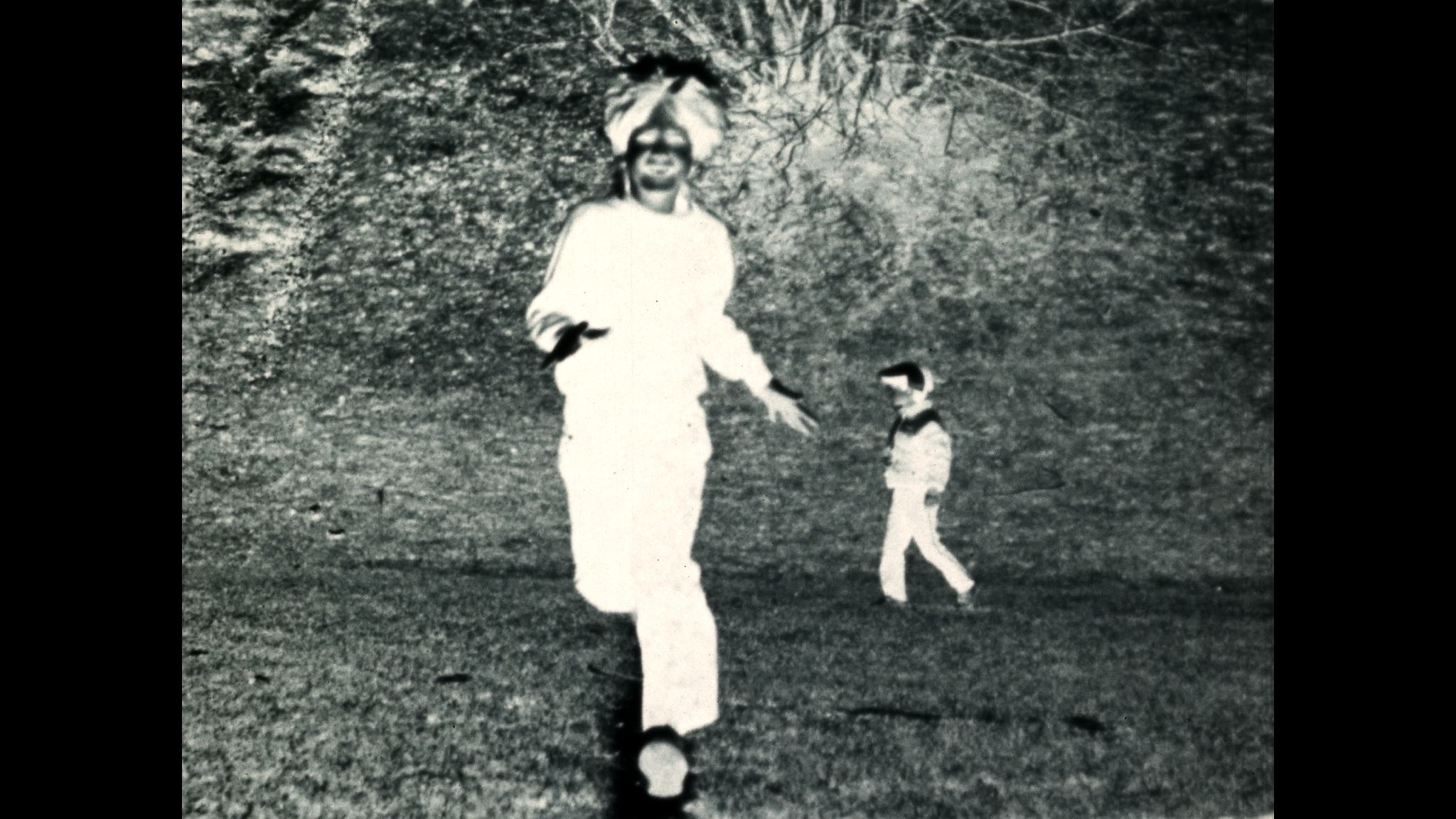

In the mid-80s Mike began a four-part film series called Narratives of Egypt. He had been obsessed since he was a kid with the work of Herman Melville. As his sister recalls, “When Mike was about six he became obsessed with Moby-Dick and my parents decorated our room in a Moby-Dick theme, with Moby-Dick curtains, bedspreads and I think we even had Moby-Dick pyjamas. Mike managed to convince my Dad to read us Moby-Dick as our bedtime story, a reading that took well over a year…” Years later Mike was still in the thrall of his boyhood obsession, still wearing the pyjamas so to speak, when he took up his camera and began to work. In the first film in the series (of four), Mike appears as a negative head floating in whiteness, declaiming moments of Melville’s text, not the story bits, but other things about homosexuality, power, naming and Egypt. He’s performing his version of the book, citing passages, like in the older days of oral culture when stories were shared aloud and declaimed in public. The second movie shows his son running towards the camera while a series of intertitles clipped from Melville’s Pierre talk about a journey into a crypt where “you peer amid vast names, seeking mine. You lift the lid, but no body is there…” The soundtrack is a looped riff from the Zombies (of course). The third movie is a secret love letter of grieving for his pal Cathy, mixed up with sex and Egyptologies.

I’ve seen these movies so many times and I don’t know what they’re about. I saw them at a moment in my life when the only movies I cared about were the ones I couldn’t understand. I could feel they came from a deep place, a fathomless address, a ground that was very near to his Mike-ness. It was like meeting him in the darkest corridor of himself. What was maddening beyond mention was that he never finished the series. Part four was going to be called Farrago, a word that his father Herman Melville used exactly once. “’I’ll break it for him,’ said I, now flying into a passion again at this unaccountable farrago of the landlord’s.” It means: “a medley, a conglomeration.” Which translates I think into bits and pieces, this and thats, the movie would feature a grab bag of avant-garde gestures.

Years later, when Mike was broken, when he limped back to Buffalo having been exiled from Mobile, unable to imagine a way forward, I pestered him about his unfinished daydream. Could this at last be the moment when he returned to Farrago, having been relieved of the burden of his former life? He had left all making behind for more than fifteen years by then, the prospect of not dying seemed remote, he sometimes talked in a slow-motion sludge of downward spirals, hardly bearing to part with the words, desperate that the phone call go on and on into the nights which had become his days. I wanted to help him, I wanted to help myself. In the end, he wound up writing a text that provided a new beginning, and eventually he picked up the camera again and began filming, but he never made the trek back to Farrago.

After he died, his son Sam rolled into Toronto with boxes of tapes and movie elements and unseen delicacies. Amongst the treasures was a large silver can marked: FARRAGO. Oh god oh god oh god. Inside the lid was the work-in-progress he’d screened back in 1987, thrown together at the very last moment in a haze of deadline panic and Gavin Bryars. There were a half dozen rolls of diary footage featuring various amours from days gone by, dressed and undressed, along with beach outings with kids, northern visitations, landscapes. We watched dumbstruck at the bits and pieces as the old dream took root again, that this long abandoned film project could at last be realized.

I began working on Farrago about two months ago. I started by copying the three movies Mike had already made, I would cannibablize these for the fourth section. And then I began to drift through Vimeo, looking for anything related to Moby-Dick, or Melville, or whaling or Egypt. Days and nights rushed past as I downloaded clips, bulking up an archive. I felt the deliciously forbidden and guilt-inducing sense that I was doing something wrong. Eating the body of the father. Why else make art if I can’t feel this feeling, savour these sensations of prison break and release, of a temporary and unearned freedom? Of a terrible transgression? I am only interested in the pleasures I’m not allowed to have, that’s why I make found footage movies. I am digging up the corpse of my friend, or at least the corpse of his pictures, and bending them into new shapes. Somehow I have to bring together Melville’s whaling and Egypt, and the question of the name. Who else but an orphan would be so obsessed with the question of the name? Here is Mike explaining it to me one more time.

“What did it mean to sign something, what did it mean to make a name? The people whose languages are scattered, whose lips are turned… in the Hebrew it says: ‘He turned their lips so they all spoke a different language. And they were scattered across the earth to go and make a name for themselves.’ The tower of Babel. The name is somehow at the bottom of language itself, a language names you. You are named by your language. It might connect to the idea that style is the man itself. That one’s style is the aspect in language of one’s singularity. Not personality or that sense of self-image which is really just a fiction. But the Real of subjectivity which is finally unsymbolizable because it’s so extensive and complicated. But it is the thing that marks you as who you are and not someone else.”

In Mike’s film series the one who does not have a name (Mike), adopts Melville as his father, and then insists that his name: Cart-mell (a place where carts meet), and Mel-ville (a meeting place of villages), mean the same thing. They are both meeting places, intersections, that describe an “X.” This is the signature of anyone who doesn’t know their name (and how could Mike know his name? He was left at the hospital, so his true signature is an X). He mines the wound, recognizing the deepest pattern of any artist worth watching: the wound is the path. A language names you. What does that mean, when you don’t have a name, when you have been refused, even by the language that inhabits you?

Melville: “Thou touchest my inmost centre boy. Thou art tied to me with cords woven of my heartstrings. Come! Let’s down!”

Sometimes I’m called upon to describe what I do in front of audiences that wonder: haven’t I seen these pictures before? I mean, non-specialist audiences, crowds of folks who don’t also make this strange, marginal kind of (sometimes found footage) cinema, so can’t be seduced by jargon short-forms and hipster wink-winks, these are people I actually have to talk to. I usually tell them that this word, “this” “word” that I’m speaking right now, I didn’t invent it. I didn’t make “this” “word” up by myself. In fact, I copied it. You could even say: I stole it. So much of what I say has already been said by others, all the words I use to start with, but even a lot of expressions (Hi, how are you, how’s it going… I didn’t invent these words, they just come out of my mouth as if they belong to me.) even a lot of my emoticons have already been laid down. Perhaps this is what Mike means when he says: a language names you. Maybe Mike is saying that language is the ground for all found footage filmmaking. This is how we live, in a world that stitches together borrowed words and pictures to create a self, we are always creating a collage with our words, cutting and pasting learned expressions in order to create our own expression. Our language is a kind of communal inheritance, it’s only the way it emerges from us, via our style, that makes us different. I can already hear the found footage filmers nodding in time. Of course, we’ve known that all along.

Mike’s pal who was also named Mike wrote me from his end of the digital graveyard: “I’ve been doing some digging myself and have found a couple of things. One is a recording session we did with two Frenchies singing an Ojibwa song; it’s the commentary between takes which is really good. Hadn’t heard it in years; had me in tears – Mickus! How can you not be!”

How can you not be? Is there any question that drives the found footage filmmaker more than this one?

Each morning I continue work on Farrago. I am deep into the whaling voyage, someone else’s lifelong obsession become my own. We are searching for clues together, trying to read the writing on the wall, making our own pyramids.

Perhaps at the last I myself will more perfectly come to resemble my own name.