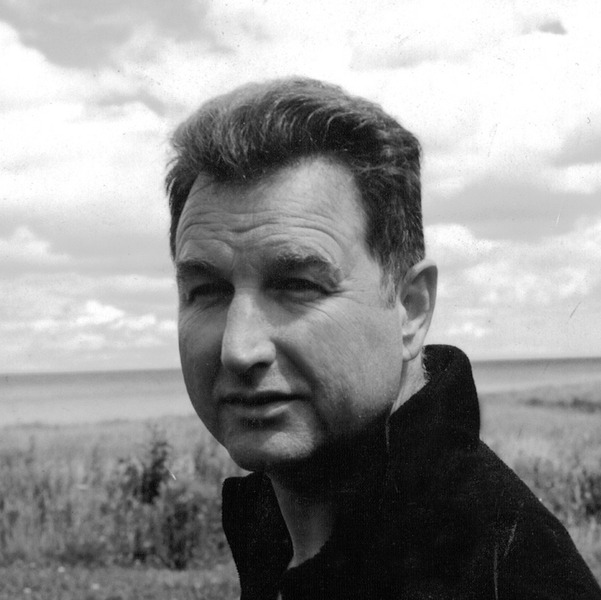

They All Disappeared: an interview with David Craig (May 12, 2013)

David: I arrived at the Ontario Arts Council in August 1988 and became the media arts officer. Judy Gouin was the outgoing officer. There had been a lot of business before I arrived, related to the Funnel’s move from their King Street East location to Soho Street, just off Queen West. They had big plans to build a new theatre and provide equipment access but they had run out of money. There was a lot of mystery around what was happening. The whole file was in suspended animation because the project of theatre building had started and then stalled. And when the work stalled, all communication stopped.

Mike: Do you know why the Funnel moved?

David: No, that was all before my time. I had visited the King Street location before I worked at the Arts Council. The only thing that was unusual was that it was so far from the downtown core where everybody else was. The facility itself was fine but it did seem like it was in its own world. It felt like a frontier outpost because the rest of the alternative art world was clustered around Queen and Spadina. I just presumed the rent went up, and that’s why they moved.

The person I never met was Ross McLaren, who had started the Funnel. I might have seen him at a screening, but by that time he was living in New York. Part of the difficulty of the situation was trying to figure out who was really in charge. The atmosphere was very confusing for me when I came into it. Most of the information I had on file were applications from prior years, there was little that I could use to analyze the current situation.

People were calling me primarily concerned with the equipment. Only members could access the equipment and there were hardly any members left. What had happened to the equipment during the move? Rumours were swirling that the equipment (an optical printer, a couple of sync 16mm cameras, a Nagra, etc.) had gone to New York or somewhere outside of the city.

Mike: Did you speak with your counterpart at the Canada Council, Francoyse Picard?

David: I’m sure I did, we spoke often. She was an interesting character, she was very committed to what she called “the cinema of resistance” and was very supportive of alternative filmmaking.

Mike: Her vision was a national chain of alternative cinemas run by the film and video co-ops. An integrated, alternative system of production, distribution and exhibition that ran across the country.

David: Nationalism was a big theme at the Canada Council. Overall, if I recall correctly, the Canada Council was still in. In the fall of 1988 there was a delegation from the Funnel that came to see me. It included Gary McLaren (Ross’s brother), David Bennell and Mikki Fontana. They had come because I was new, and they wanted to update their situation. There was such an atmosphere of paranoia on their part about whether or not funding would continue. They had heard some of the concerns that artists had about the equipment. It was an odd meeting as I recall. David Bennell had been working on the theatre, but it wasn’t completed. A lot of the update was at the level of: someone didn’t show up to do this, or we couldn’t do that… It was an awkward situation where I didn’t have enough of a relationship with the people running the organization to figure out where they were in the whole chain of command. Then I was getting people calling to tell me the organization was closed, there was no communication, the equipment wasn’t there. There was a concern that whatever resources the Funnel had were being sequestered under the devious command of Ross McLaren. People were saying Gary, the new Funnel director, didn’t have any real authority, that he was acting completely under the orders of Ross.

I was plugged into the politics of access centres, having been involved with the Centre for Art Tapes in Halifax. I had some involvement with Charles Street Video and Trinity Square Video, two organizations that had moved shop and upgraded their facilities. And I was involved with ANNPAC, a national coalition of artist-run centres, before coming to the Arts Council. But the paranoia around bureaucracy, the underground atmosphere, was unusual. It was Funnelesque. Smaller organizations are prone to taking on the personalities of the people who run them. I certainly got that sense with the Funnel.

Mike: I worked for the Funnel in the summer of 1988 on a short term, federal employment grant. The move from King Street to Gary’s warehouse on Stewart Street proceeded because the Soho Street space wasn’t ready yet. One of my jobs was to answer the phone, and it rang constantly with people complaining that their cheques had bounced. Some of the amounts were as little as ten or fifteen dollars, and these calls were made before the move, before anything was spent on construction. What had happened to the Funnel’s money?

David: It was like a black hole you had no insight into. I also received calls about bouncing cheques from some of their creditors. Again, this is quite a long time ago. I got there in August, and the Funnel’s situation landed on my desk that fall, by October it was a major concern. The renovation stalled because they ran out of money. The equipment was sitting in Gary’s apartment, and artists in the community were convinced that with the renovation running aground, the equipment would go to New York. That was one of the main concerns.

Gary, David and Mikki came up with a proposal but its credibility was in question because cheques were bouncing left and right. They had an operating grant from the Ontario Arts Council, and they were also receiving funding from the city and the Canada Council. They were trying to get special transitional funds, but the Arts Council doesn’t fund capital costs. I suggested they submit a revised proposal with a financial update.

When they submitted the new proposal I organized an assessment committee: Jane Perdue, Seth Feldman, Marc Glassman, Annette Mangaard, Gary Popovich, Barbara Fischer, Martha Davis, James Quandt. In a jury process, the jury has complete autonomy over their decisions. If they say: this number of people will receive grants and these people don’t; that doesn’t get tampered with. But with an assessment, it’s the officer’s responsibility to make a recommendation to the board, predicated on the advisor’s comments. I spoke with a number of different advisors, some in person, some over the phone. I spent a lot of time talking to people about the Funnel. There was definitely the feeling that the Funnel had to get beyond themselves and become a more public organization. The group that was the Funnel at that time weren’t really capable of making the turn around, they certainly didn’t have a lot of support from the community, and there was a sense that it was becoming a morass and throwing more money at it wasn’t going to make it better. When I went through the proposal the numbers didn’t work for me, and my sense was that I couldn’t really support funding it.

The procedure was that after the advisors weighed in, I would have to write a detailed memo to the board describing the situation, the determinations of the advisory process, my analysis of the budget and final recommendation. I was quite trepidatious about it because it isn’t very often that you close down an organization’s funding. I knew a lot of people involved, some were friends or professional colleagues. The proposal was filled with grand plans for the new theatre but I thought that there wasn’t enough tangible evidence to support them. There was a sense that what was in the application didn’t reflect what was going on whatsoever. That was one of the most difficult things. It all sounds good on paper, so why am I getting all these phone calls? People would ring me up and say, “You’re not going to fund the Funnel, are you?” It was a weird situation. Why would I spend that much money on a project that was going to fail? But I was paranoid, I thought I had just come into this job, and the first thing I do is kill the Funnel. That was definitely part of my thinking at the time. I was the guy who killed the Funnel. But my strong sense was that the community was fed up, and I made the recommendation not to support them. And subsequently the fallout was a whimper not a bang. They all disappeared.

Mike: Was it unusual that an organization be recommended for de-funding?

David: Yes, it was very rare. Most artist-run centres are very well run, and their longevity is a testament to their good management. It’s remarkable to me that some are still in existence, considering that some of these organizations were founded on temporary unemployment insurance grants in the early seventies. By nature, lots of organizations have come and gone. But the organizations in Toronto have had tremendous staying power, mostly because they have been ably managed. There have been ups and downs. Trinity Square Video had several moves, Charles Street Video had several moves, LIFT had its shares of moves, and these are difficult transitions for any organization to make whether they’re big or small. By and large, they’ve been handled impressively.

One of the biggest fiascos I was involved with was the Euclid Theatre. It was more extravagant than the Funnel could ever have imagined. It was one of the most successful fundraising campaigns in the non-profit sector, they raised over a million dollars in capital funding. But nobody thought about programming. They presented an ambitious program to the Arts Council, but when I added up the numbers for theatre rentals, administrative costs, guest filmmaker fees and rental fees, they were looking at $5000 per night. If you extrapolate from this series to the number of nights available to screen, you’re talking a huge amount of money. A theatre like that had to run on a mixed economy, there had to be self generated revenues. The cost of its programs weren’t sustainable, there wasn’t enough funds at any of the arts councils to support it.

It was hard to justify putting more money into the Funnel, no matter how glorious its history. There was such tremendous animosity and anxiety in the community because artists worried the experimental film community would fall apart without the Funnel. There was a very strong sense of what experimental film was. There were major concerns that this bastion of technical support for experimental filmmaking, and the programming venue, were necessary community components. On the other hand, my sense was that if you don’t have the administrative infrastructure, or community support, and you have a really bad financial situation, and a half completed renovation on a space you can’t afford, none of it added up.