Intro

Sometimes my friends invite me to a place like this, into a school, where people young and old are performing together the act of education. And my pals are most eager of all to show me the wondrous student, you know the one, the person who has written that incredible essay, oh they’ve carved the most perfect sculpture, they have the best ideas, they’re so smart and talented, even their shit is packed up and shipped off to Soho galleries where eager collectors lay the big money down.

But I have to admit that, when I was your age, I was not that person. When I was in college I made huge quantites of trash, it was all vague and incomprehensible, I didn’t know what I was doing, though I was possessed of an unrelenting drive to keep doing it. But tell me, I need to hear a few words from you. What are the three qualities that you might need as an artist, that you need as an artist to… build a body of work, to have a practice, to be “successful.” What kind of qualities do you need as an artist to “make it” or even: to endure? Anyone?

Let’s just sit in this awkward silence until three brave people offer up some ideas. What do you need as an artist? What do you need? And how might this frame, this frame of what we call education, how might this frame support those needs?

Artists

When I was in school, there were talented students around me, oh yes they were smart, and dedicated, and they made incredible things, one after another. And then they graduated, and soon began to live decent and responsible lives. They bought houses and cars, they had relationships, they got real jobs. They were still gods, but now they were lending their genius to the corporations.

What I’m saying is: the best artists in this country, the best artists in every country, don’t make art. They are too busy making detergent, or babies, or ecofiltering systems for houses or doing drugs or whatever. I don’t know about you, but that gives me a lot of relief. Whew, I don’t have to be the best, I don’t even have to be in the top ten.

I was never smart, or talented, I never had the answers. I was paralyzingly shy, I hate groups, I can’t network, I find self-promotion embarassing and humiliating. But I had three qualities that helped me. Number one: I can work harder than anyone else, day and night and day and night. Of course my stuff was crap, but year after year I kept throwing myself against the wall, and one day the wall started to give a little, and slowly slowly the work got better. Number two: The second quality I cultivated as an artist is luck. You have to have luck. You need a break, a leg up, a body up, someone to open the door. Number three. The third quality is more mysterious, it has to do with what my pal Mike called our neurotic structure. I’m speaking of course about the organization of the self. When do we organize the self? Well it remains a work-in-progress, but major shifts occurred in our “developmental moments,” when we were kids, not in control of our environment, our emotions, our bodies, those tender helpless moments when the slings and arrows arrived, the terrible wounds that we were forced to build a personality around. My personality, my first line of defense.

I’m suggesting that each of us is marked by a series of personal catastrophes, they are personal, they belong to you, and out of those experiences each of us builds accomodations, we have to get through it somehow, right? We have to survive, so we develop traits and tendencies that allow us to get through. And then later, even when those circumstances aren’t around anymore, our accomodations, the defense systems, they’re still working. Some people’s defense systems look like running for the president of the United States. Other people’s defense systems look like art.

**

Michelle

Can I give you a for example? For example, let’s take my pal Michelle. Now Michelle is an extremely capable upright citizen. She can always be depended upon, she’s reliable, and strangely, for a young person, she can talk the talk of corporations. She can rattle out all that official sounding language. And she has perfect hair. I mean that her hair cuts this perfect line across her forehead, like Michelle it’s exact, precise, measured.

So one day by accident, which is how all the important things in our lives happen, one day I met her dad, who is a larger-than-life speechmaking machine. He is a little louder and funnier and drinking harder than anyone around him. And as soon as I saw him I thought: w-o-w. Can you imagine that guy as your dad? I mean anyone who is so busy entertaining like that and always being the centre of attention, must need a lot of attention. The reason I’m so smart, the reason I’m so funny, the reason I’m so loud – it’s because I need attention.

You know there’s some people who like to stand up here, at the front of the room. We do it because we need attention. There’s always a cover story like: I’m doing this for your good. But actually, I’m doing it for my good.

My body, and the bodies of the other people who like to stand up here, who you see proclaiming from the TV sets or the steps of government buildings– our bodies are like holes. You pour attention into us, and it drips right out. Now how is someone like that, someone who is filled with holes, someone like Michelle’s dad who I met at the party, how is someone like that going to behave as a dad? Well he’s obviously not going to look after your needs, instead he’s going to pull the old switcheroo, and make sure you tend to his needs.

But wait, you say, I’m only a child. And he’s an adult. Sorry pal. In this family, you have to be the adult, because the old guy is full of holes, and it’s your job to keep pouring attention into them.

The moment you, as an eight-year-old, as a ten-year-old, begin to look after your larger than life dad, tucking him into bed after one too many at the bar, or making him breakfast and nursing him through the hangover – there is the cut, the wound. Because of the switcheroo, you’re not getting the care you need, you’re giving it to him. So you start building a whole personality as caretaker, as someone that can look after others. Have you met people like this? Are you that person? You never had a childhood, you’ve been an adult all your life, so you always appear composed and together. Though behind that reliable can-do togetherness, is the child that has been abandoned, and you are also that child with all of their unbearable hurt and pain.

You work hard to make sure that no one will see them, and when your efforts succeed, and the child is invisible, sometimes it makes you mad. Why do you think I want what I want? Meanwhile the person you’re with is wondering: why the fuck are you so mad all the time? The anger might be the presenting symptom, but it might be something else: like drugs, or overworking, or shopping, some way to numb all that pain.

How to shake the fundamental feeling that the reason dad didn’t look after you is because… you weren’t worth looking after. Actually, you’re invisible, your needs don’t count. You only have value, or worth, or self-worth, when you are in service to others. That my friends is the neurotic structure. And some neurotic structures are so good for artists, while others are good for being meth heads or landscape architects or the owners of family restaurants.

Samskara

The Buddhists have another name for these neurotic structures. They call them samskaras. You can hear the word scar in there. Samskaras are physical, psychological, cultural grooves. You know like a groove in a record. OMG I’m getting mad again, here we go again.

Every person in this room at this moment is showing me your samskaras. You know the body, when the body is created, it begins in the middle and it grows out in two sides. And one side of the body is strong and powerful and beautiful. One way of saying this is: I’m right handed. Or: this is my good hand, my strong hand. I’m left footed though. This is my strong foot. And if this foot is strong the other foot must be… Weak. The other side is the shadow, our shadowy life.

Very often we like to lean, have you ever noticed this? How your friends, your family members, how you yourself like to lean over on the same side again and again? You’re leaning on your strong side. Most of you are leaning in that direction right now. But it’s not only our bodies that are leaning in a certain direction, moment after moment, day after month after year. Our ideas are also leaning in a certain direction. Our emotions are also leaning in a certain direction. The habit pattern of leaning, the habit pattern of the way our organs develop, the habit patterns of our feelings, these might be called samskaras.

There’s a word we use here in North America that is like the word samskara. It’s a four-letter word, and the word is shit. What I’m saying is that if you want to be an artist it is your duty, your obligation to know your shit.

But of course it doesn’t stop there. Each of us has our own bundle of samskaras, our own scars. This building has samskaras. This land, which was stolen from the Indigenous people, who were hunted down and slaughtered, this land that we’re on right now has samskaras. It belongs to the Onondada Nation, who were granted title in the Treaty of Canandaigua in 1794. They tried to stay neutral in the war between the American settlers and the British, but the Americans attacked them. When the Americans won, they signed the treaty granting them title to their land, and then of course they were backstabbed and killed and the survivors forced to leave.

This city of Syracuse, this country, this imperialist colonialist power of a country is busy killing people around the world every day. It’s so hard to stop the killing, isn’t it? The force of those grooves, those deep habits, is very hard to give up.

There’s a word we use here in North America that is like the word samskara. It’s a four-letter word, and the word is shit. What I’m saying is that if you want to be an artist it is your duty, your obligation to know the shit of your university, your land, your city. Whatever you feel your neighbourhood is. It is your duty to understand what those habit patterns are.

**

And when you make that dig, that archaeological dig into the roots of your culture, which are also the roots of your own experience, you’ll find things that are difficult and unwanted and hurtful. And the question is: what are you going to do with that? How are you going to deal with the unwelcome and the unwanted in your own life? Those soft and vulnerable places. Oh I know I’ll just watch Netflix and the bad feeling will go away. I’ll just buy a new pair of shoes. I’ll go have sex with someone who looks just like my dad. That always works.

Practice

So this brings us to the question of practice. You hear this word a lot in the art world, and also in some other worlds like dance or yoga, worlds that have something to do with the body. As if the question of practice and the questions of the body can’t be separated. Because of my personal samskaras, because I had the shit beat out of me when I was a kid, I’m forever hiding from life, shrinking away, afraid and fearful, and I express this fear by… overwork. I am rewarded for this, people imagine it’s a good thing, unlike say a heroin addiction. People rarely say: I’m so proud of you for a heroin addict. Whereas they enjoy saying, it’s so great that you work so hard. But the addictions come from the same place. As Gabor Mate notes, we live in a culture of addiction and we are all addicts. But the addiction is only the presenting symptom. The problem isn’t the endless drinking, the problem is what led to the endless drinking. The endless overworking.

So my practice, because I like to overwork, is about something that can be done day after day. It’s a steady drip, one after another. Others like to binge. Their practice means getting down to the serious thing for a week or two and work like demons day and night and then take the rest of the year off. That’s not my style. I like to chip away at it, day after day. One of the big parts of my practice is listening on the radio to a program called Democracy Now. Have you ever heard of that show? It’s not corporate sponsored, so unlike most news programs it doesn’t promote corporations, which means it can sound pretty different from a lot of what passes for news in this country. And I like to do yoga while listening, so that the news can soak into my body, one breath at a time.

Killers in America

So one of the terrifying leylines that Democracy Now has been following, is the systematic, day by day slaughter of American citizens by the police. And not just any citizens. but especially black-Americans. Doesn’t matter if you’re ten years old or sixty, the police come and shoot you, or choke you to death, or torture you in their secret warehouse building in Chicago. Three people are killed every day in American by the police. When I heard this news, I decided that for a year I would only read books by black-Americans. This became another part of my practice. I’m listening to Democracy Now, I’m doing yoga, I’m reading James Baldwin and Claudia Rankine and Fred Moten and whenever I read something that really sticks to me I jot them down. And I’m only listening to jazz. I’m creating a frame, a frame of reception to receive the cultural scars, the cultural samskaras, the deep grooves.

Mom

My mom was born in Indonesia, she’s half-Indonesian, half-Dutch. I’m also a person of colour, but pass as white. My mom on the other hand looks brown. She looks like an island person. So one morning we’re at the fruit market, and the women behind the counter doesn’t want to serve her, it’s as if the lady can’t hear a word my mother says, but when anyone else talks, it’s loud and clear. Number two: we’re waiting in line at the drug store, long slow line everyone is a senior, and when it comes to my mom’s turn a white guy just steps right in front of her and lays his stuff down. When my mother says “Excuse me” he looks over at her and says “Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t see you.”

I can’t see you even though you’re standing right in front of me. Because the way my samskaras work, only white people are visible. The history of racism is an accumulation of gestures large and small, and those gestures live in our bodies. I believe that our pictures, in order to make a real picture, it requires roots. Roots in our experience. When I stand with my mother, and feel the racism she feels, it gives me the roots I need to undertake the movie I’m going to show you. Unfortunately, I’m only going to show you little bits at a time, and then I’m going to stop and talk about it. Sorry about that.

(Fats

A few years ago I started working, loosely, on a movie about artists, and I’m looking for a last artist to round it out, and it takes me a long time to find the name. But at last, it arrives: it’s got to be the great Harlem jazz pianist and singer, Fats Waller. This name, this urgency, comes up out of the reading and listening, out of my mother’s experience.) Can we get the lights?

(Dark theatre.)

Let’s start with black and black. The question of blackness. In the preface to his play The Blacks, French writer Jean Genet, who is white, a convicted criminal, gay, politically radical, wrote this: “One evening an actor asked me to write a play for an all-black cast. But what exactly is a black? First of all, what’s his colour?”

Play next ten seconds.

The title doesn’t appear all at once, it arrives slowly, one letter at a time, as if we needed to make an approach. This strategy of slow revealing will be taken up by the movie, which doesn’t deliver us to Fats Waller right away, instead we make an approach, we approach the subject, one part at a time.

So let’s begin with a story, it’s a story of violence, of white-on-black violence. It’s a story about an escape artist, how the artist uses his talent to escape, how he sits surrounded by killers with only his music to protect him. It’s a story set in smoky nightclubs and gangsterisms, so let’s steal a bunch of film noir clips and hurl them together, while the son of Fats tells the tale. After the title we have the first movement, and it looks like this:

Play opening scene

So the scene begins and ends with this same shot. A sheet of rain, a man walks through it into the scene – that’s the beginning, and when he walks back out of it, that’s the end of the scene. This is called framing, right? Framing the scene. The opening scene has a frame around it, and inside that frame we see variations of this opening and closing shot. Every shot is mostly black, the lighting is harsh, it’s a twilight world, half glimpsed, shadowy, violent, masculine. The first scene serves as an introduction and an establishing shot. It gives us clues about what’s going to happen.

Let’s have a look at scene two. Where do we go from here? What would you do next? Can anyone offer a suggestion? What should follow these pictures?

Play Scene 2, stop around 2:50

In place of the artist’s image, we hear an oral signature. The face is withheld, the face is held back, instead we hear the voice of the artist skatting. He’s already inventing his own language, his own rhythm, based on his own samsakaras, as he navigates his life.

The movie should properly begin with historical New York because the subject is historical, but instead we have these scenes, fresh, contemporary, live. It’s as if the past exists only as it can be imagined from this moment. And that this present moment contains within it voices and echoes from the past which have shaped us, which have shaped the way we see and feel and hear. In other words the past is a living thing. A samskara. And the aim of this movie is to feel the way the past might be living right now.

Every biography is a kind of resurrection. It drags its subject back into view, as if they were still alive, or that they are living again because we are granting them attention. The question of the movies, the question of art, is always about attention. What is worth paying attention to? And how are we going to do that?

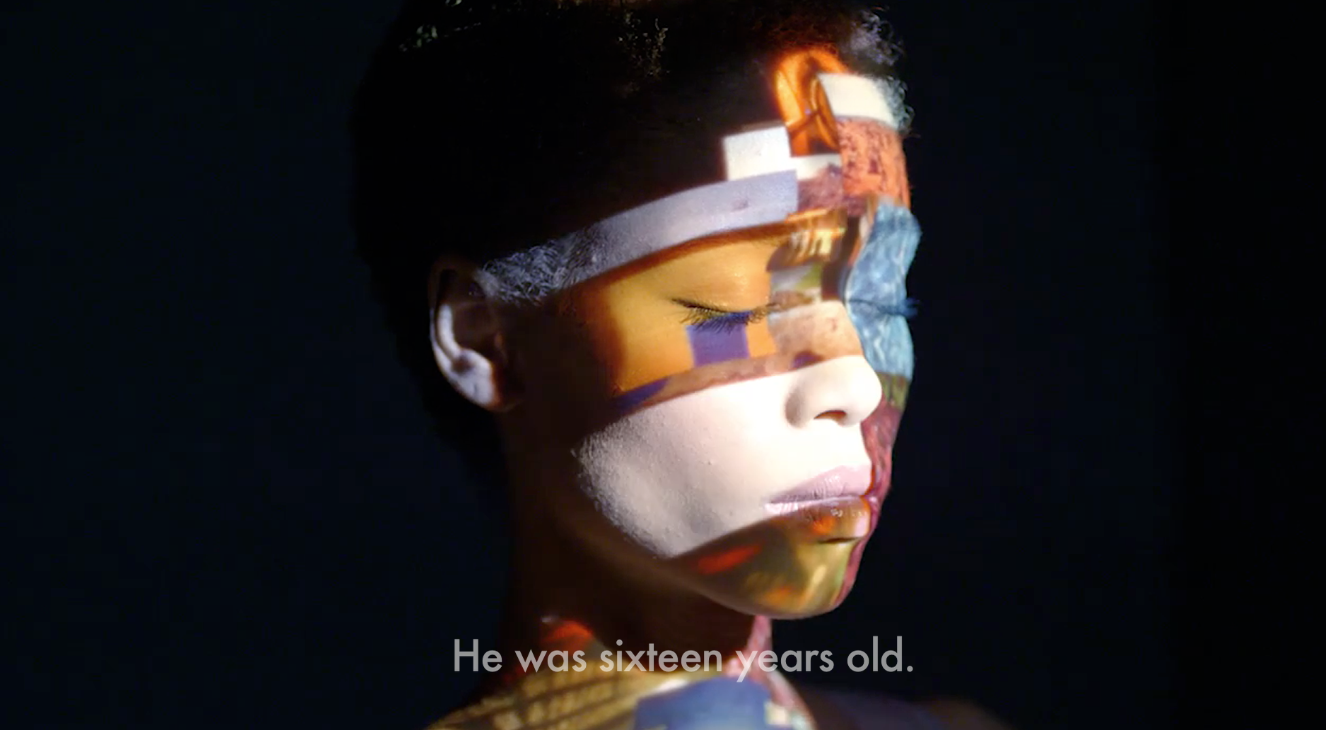

PLAY SCENE THREE end 5:38 after nokia commercial

That of course was a Nokia telephone commercial, in fact, we just watched two commercials from the same campaign using the same model, they both looked great and deliver us to the question of projection, of how we recreate people according to our projections. The pictures in this movie are stolen. They have been made by jean advertisers, telephone and music companies, all of them selling, as Naomi Klein advised us, they are pitching us a way of life, a lifestyle, a brand. Why not take some of these pictures and turn them in another direction? Let’s reframe them, let’s put them back to work.

The titles, which appear as audiovisual graffiti, scribbling over the image, captioning the pictures, like a comic book maybe, offer us moments of the artist’s life, perhaps the way he was wounded. I’m trying to talk about his samskaras, the physical, emotional, psychological grooves that his personalty was built around. What does it mean to be part of a large family where so many children died? To be a survivor. And what does it mean to find your mother dead on the floor, followed by this incredibly indignity, this obscenity, of having your beloved hoisted out the window, where everyone can look on, as her dead carcass lies outside. And then vowing you would never step into that house again, leaving home at 16.

OK, so what comes next? What are we going to see, what are we going to hear, now that Fats Waller has left home?

5:39 Fats’s son speaks

OK, so after the intertitles we return to the voice, the first voice we heard in the movie, the voice of the son of Fats Waller. The images are also similar, they are an echo of the opening scene – it’s night time, low light, shadowy, film noir.

Then I want to introduce a second speaker, and to give him some momentum, some push, but also to separate the two voices, let’s add some music in there, which has to be piano music, which should be the music of mr. Waller, only his tunes are so raucous, they’re all up here, whereas I need the music to lay back, to provide a spare accomplaniment so we can hear the words, so I steal a bit of something else, can’t remember who right now, just some minor chords, and then we hear this whisky and cigarettes voice, the beautiful voice of the speaker. And this voice carries information, there is content, but more important than that, it has what the Buddhists call a vedana, a feeling tone. You can feel in your whole body the voice of this guy, you listen with your whole body. The tone of this voice delivers us into the body of Fats Waller. Or that’s my fantasy.

play tape 5:39-7:10

So we’ve just heard this powerful testimony, then I need space to digest that shit. To absorb that whiskey voice, that history, so there’s some dreamy pictures stolen from here and there, thank you very much Vimeo. And then the piano ends, the music ends, and we go to black. There’s a brief space, and then this movement which is made of two voices, the voice of the son and the whiskey voice, and then this movement is over.

Now we’re going to start another scene. How do we start a scene? Often with an establishing shot. Where are we? Well, we’re in New York City. So let’s have a look at this city – we’ve already heard the voices, now we’re going to come back to the text on screen.

play tape 7:10-7:58

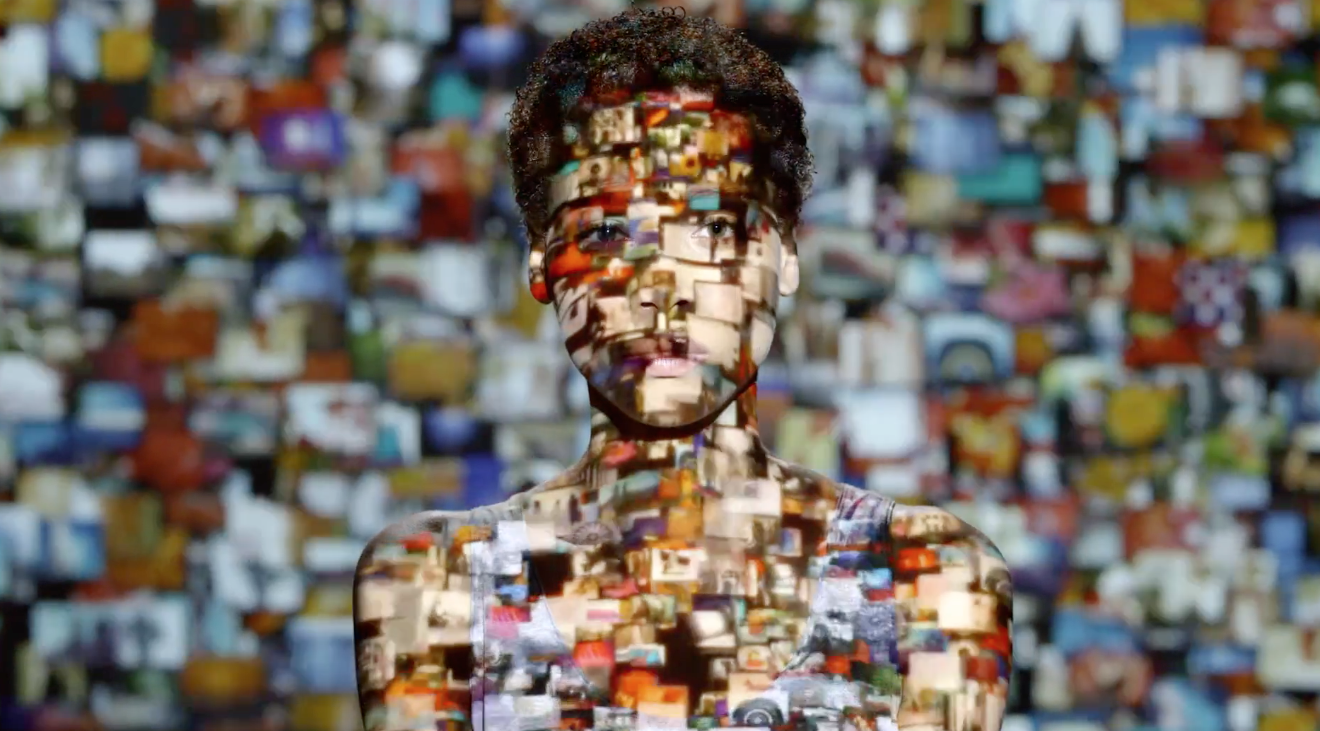

The music of Fats Waller, which we haven’t heard yet, even though we’re eight minutes into the movie – it’s bursting with life, bursting out of his oversized body, bursting out of language, past the borders and limits of language, abadeebadabetada. This biography is also bursting out of his body and occupying all these other bodies, just like a dream, where you have all these people in it, all them variations of yourself.

And then we hear a voice, only it’s a voice that is not part of Fats Waller’s family, or his old musician drinking partners. It’s a voice I first heard on Democracy Now, the voice of Ta-Nehisi Coates, one of the most important writers working today, an urgent and necessary voice who is unpacking and elaborating the difficult question of racism in this country, and he’s talking about it as a system.

I’m going to try to slide his voice in there, lay it up over those beautiful faces, and start it off, like a boxer at a ring, at the sound of the bell. The bell will announce to the viewer that the voice is about to begin.

play tape 8:04-9:24

Ta-Nehisi Coates says: “I think our criminal justice system is working as intended.” And then there’s a space. Because I need time to digest that. What about you? You mean: the fact that all those black kids are being hunted down and shot by police – that’s quote “the criminal justice system working as intended.” That’s what they want? And then he doubles down and says: if your intention is to jail mass numbers of people… And he gives us another riff, but the words come so fast, the information is so hurting and fulsome that I put in some clanging sound effects, a twist off cap, a brick dropping, a clap, so he just gets off a sentence or two and then click, and pause, and then we can digest some more.

Because listening is the most important part of conversation. It means not being able to include that many words, but by choosing just a few I hope they sink in. Do you know? I’m making a harsh cut, a series of cuts, I want to get you to hear just a very few things, and then I need some time to allow those things to sink in, so you can feel them in your body. Let’s watch that sequence again.

play tape 8:04-9:47 – end after b/w neg piano ends “There’s some ways to sound like an authentic stride pianist”

So here’s the first time we hear the music of Fats Waller, and we hear it via this white guy who is promising us that he can teach us how to sound “authentic”, to sound “real”, like an “authentic stride pianist” as he says. Which brings us to the question of well, what is real?

And this provides an introduction to a new movement which is going to allow us to here another Fats Waller tune, a song that was written out of pain and protest, a song which takes up the themes that Ta-Nehisi Coates introduces us too – that racism is a system operated by the legal system, the police, and the government (and of course carried out by some of its population).

play 9:47-12:31 black and blue song, ends with kid at school

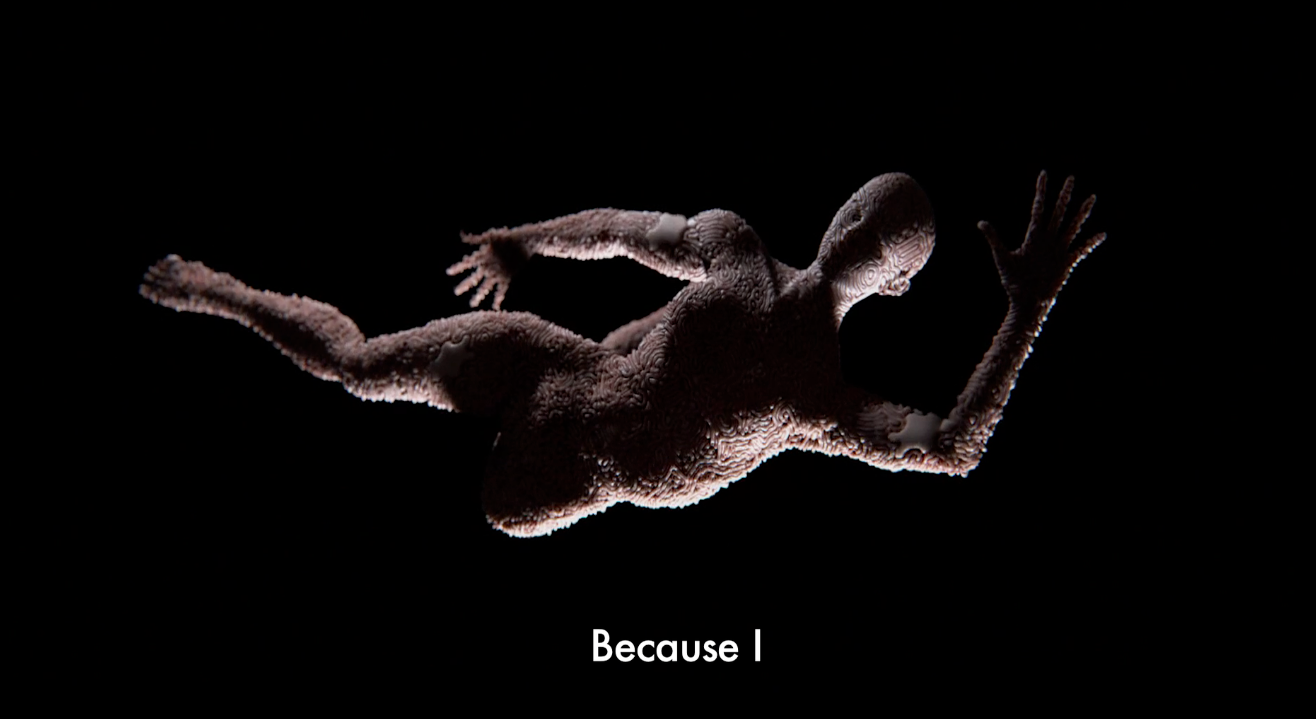

While the Black and Blue song plays, titles show us the lyrics. The pictures are what you can find a thousand miles of on the internet. Some diligent student, at a place just like this one, has been busy creating virtual bodies, and turning them different colours and adding spikes or horns or watery limbs. I look at them as exercises, they don’t have any content that I can see, except for a demonstration of technical mastery. I feel so out of control of my life or my emotions, but here in my computer universe, I’m the one in charge. I’m the commander-in-chief.

The second part of the song, of this movement, takes a vamping note from the piano, and loops it, and while it’s looping we see pictures of someone falling, and they fall for a long time, because racism might be like… falling for a long time, and we see the broken faces, and then a kid going to school.

Every image is a kind of school, isn’t it?

When it’s time for another voice to enter, it is announced, the way in the olden days a courier would say: here comes the queen! or the way people make introductions the way we heard Emily make today. I want to signal that there’s going to be a shift, an important speaker, so instead of another bell, we hear the sound of scraping metal against the repeated piano vamp, and then we hear a voice, an older voice returning. And then we’re launched into the next scene.

play 12:31 from kid in school to 13:35 – Fats in elevator

The movie is 20 minutes long, and we finally see its subject 12 minutes into it, dressed as an elevator boy, asking the white boss for a break. The boss assures him: “Your place is right here in the elevator.” Tell me, do you have a place? Have you been placed? Do you know your place? The main character is not named or identified – how would you know that this guy is Fats Waller? And what does it mean to be a world famous, smash bestselling musician, but the only job you can get in the movies is as a servant, the underclass, someone degraded? Put in their place. Is it fair or unfair to show him in this way? Why can’t we see him in his moments of triumph, shining above it all, resplendent in his talent, his largesse, his beauty?

And then the haunting pressing question: where do we go from here?

What has to be said now?

play 13:35-16:16 After Fats in the elevator: jean commercials, end with multi-screen TVs

You hear in the background some noodling on the organ, just screwing around, random notes. That’s Fats Waller as a teenager, his first professional gig was as a church organist, and it was recorded back in those days. What we hear in this movement are four voices, one after another, giving us a snapshot of racism at that moment in America. No hotels for blacks. Wow. They jazz musicians were playing the hotels, but they couldn’t stay there, couldn’t walk in the front door. Audiences were segregated, officially, legally, enforced by law and police – segregated. It’s an apartheid state, that’s what is being described. Does this belong in a biography of an individual? Or perhaps we could ask: how could you leave this out, this central question, this terrible spreading stain of racism. How could Fats play music, what music might he be allowed to play, in this system of apartheid, and in the face of this hatred. You know who is lined up against you? It’s only your government, and the legal system, and the police, they all hate you. How does that shape your experience? How do the samskaras – the habit grooves – of your society, change the habit grooves of your own body and your own expression?

Instead of the sequence ending with darkness, with a pause, we find this image of multi-screen surveillance monitors, stolen from the internet, thank you Vimeo. It’s a moment of respite, a palette cleanser, an extended closing chord, before we dig in again, and offer a final essayistic reflection on Fats, where we’ll return to the old strategy of titles appearing onscreen.

begin 16:40

The image of the main subject arrives near the end, or at the end of the movie. It’s as if the movie, the “biography” of Fats Waller, is only an approach, is only a series of pointers, bringing us to the place where he might be seen. The question is: why? Can anyone tell me why?

As someone who makes pictures, one of my central concerns is the question of visibility. How do I make someone or something visible? Now wait, you’re going to tell me, let’s just whip out my phone, and without even a click, I’ve taken your picture, I’ve uploaded it to my instagram. But the internet has introduced a new kind of invisibility. There are so many faces, that I can’t remember your face, even when I see it on Instagram. My theory is: that you can make something invisible by not showing it, or you can make something invisible by showing it too much.

There are many ways we create invisibility, or to create conditions where it’s hard to see someone. The racism – which is a fancy word for hatred and ignorance – the hatred, the systematic hatred that we hear about in this movie, makes Fats Waller difficult to see. We can only meet him through the samskaras, the deep habit patterns, of our culture. In this moment. And our culture is a racist culture, a culture of hatred.

How can we work together, how can we work on our own, to resist, to work against this culture of hatred? How could we work to create new forms of visiblity and invisibility, new platforms and new hide-outs? Could our pictures do more than serve corporations? Could we find a way to touch our own difficult places, to accommodate our own grooves, and let them touch the grooves of our culture, so that we make pictures that have roots, that have roots in experience? Can we stop the old loops, and start up some new ones?

Those are some of my questions, perhaps you have some of your own.