Cushion

For the past few years I have spent some of my happiest hours sitting on a cushion. Perched on this blue rectangle I am wordless and unscreened, without any program of events mustered for distraction. Instead, I am invited to watch my own mind at work. What I can’t help noticing is how this mind likes to jump restlessly from one subject to another, riffing on stories, finding particular enjoyment in attaching old tunes to new faces. In each story, even when I’m asleep, I am the main character, and there are certain stories that allow me to play favourite parts. The wounded lover, for instance. The good friend. How I love to spin these stories again and again. Deepening the groove, running the stylus into those familiar places. Even when the stories feel bad, they feel good. I return to them again and again, as if they were me.

Best Friend

The restless mind that I notice on the cushion doesn’t get any quieter when I’m around others, not even when they’re dishing the most white-knuckled, emotional thrill ride of their lives. The interior monologue goes right on like a stock exchange of the heart, providing a steady flow of updates and revisions, ensuring that I am hardly ever here, right here, in this moment. Even when I am listening to my best friend narrate his latest relational arm wrestle, I am only admitting phrases, absorbing moods and gestures, witnessing trends. They say that Wittgenstein could hum an entire symphony after hearing it once. But I am too busy listening to my private jukebox to be able to absorb the symphonies that are unfolding all around me. And I suspect that I am hardly alone in this, that I am walking around in a city where most everyone is tuned into their own, privately-run radio stations.

Watching Movies

As someone who makes movies, I’ve been wondering what happens when I watch them. How much of a movie am I actually seeing? Because I used to love the feeling of emulsion running through my fingers, I know that there are twenty four individual frames rushing by in a single second, each separated by a black bar. But my eyes are too slow to catch the darkness between these frames, or even to see what is actually being presented to me: a series of still photographs. The object that I hold in my hands, the strip of film, is not my experience of the movie at all. Partly this has to do with my dull attention, though my taste for difficult and irritating movies has allowed me to sharpen those edges a little. But even so, the plenitude of each image, as it flickers away, is not available to my slow motion seeing. There is already too much, and so I am forced to make a choice, focusing on certain parts of frames as they hurtle past, picking out a spot of light on a couch or an eye’s suspicious glinting, whatever is most likely to attach itself to the story I am already telling myself as the movie thunders overhead, adding its own layers of distraction.

Watching a movie is like having my glass filled in the first minute of a meal, and not stopping for an instant, simply going right on pouring that long jug into the already-filled glass. After an hour and a half the jug is finally empty while the glass is still full. In the end, when it’s all over, there is water in the glass all right, no question about it, but is it a reasonable reflection of what used to be in the jug? If the jug of water is the movie, and my attention is the glass, how much am I really able to retain or recount? Or is this beside the point? And the spill, the overflow, does that settle into what we like to name the unconscious?

The Present

Try this experiment at home. Before turning to the next word, the next sentence, just wait up for a moment. Close your eyes, and concentrate on your breath. Try not to change your breath, just observe it coming and going, all by itself. If you perform this simple exercise for a minute or two, you’ll soon notice your mind wandering into one thought loop after another, and there are two primary characteristics of these thoughts: they either concern events that have already happened, or things that are going to happen. The future and the past are the primary modes of our restless minds. But movies, for instance, are not being shown in the future and the past, they are being shown now. One of the difficulties of seeing movies is that we aren’t here and now, instead, we are there and then, we’re once and never, or caught up in future fantasies. The science fiction of our lives. How can we concentrate on a movie that is flowing past when we can’t still our own minds, when we can’t stop ourselves from endlessly digressing, restlessly racing from one disconnected thought to another? The old Yoga joke: where do you hide something to ensure that no one will find it? In the present.

Projection

This is the commonplace. The voice sounds below a whisper and you find your head nodding in agreement to its sub-audible, self evident truth: if you show your movie, it will be seen. You’ve done the difficult work of manufacture, of turning yourself into a factory, and now that the new line is ready, you roll it out for the gatekeepers of festivals and museums. Eventually, some of them say yes, that’s for us. So you get this opportunity of exhibition, of what psychiatrists like to name projection. You are going to project your manufacture into public space, and when you do it will be seen.

Missing

But after some decades of festivals new and old I can’t help noticing how little remains once the celebrations have ended, and the last chairs have been folded up, and the shiny programs are stuffed back into the recycling boxes. Hardly a week old, they have already grown useless, even sentimental. While I am trying as hard as I can (am I?), most of the work I see, I don’t see at all. Most of the movies that shines up onscreen rush past me, and I miss them. How did Roland Barthes put it? That his favourite books were the ones where he never skipped the same passages. In other words, even in the most cherished texts, the ones he preferred to merely human company, the ones that changed the way language named him, his attention wandered, retreated and returned, creating gaps. Perhaps it is the creation of these gaps that we call reading? What Roland holds in his perfect hands looks just like a book. Only the most astute reader might notice that many of its pages are blank.

Motion pictured attentions are more difficult than books, in part because they need to arrive at an exact time, unlike a book which opens its spine whenever I am ready to enter. Always available, and always in the same way. What a reliable seduction. Though in the world of the book, I am asked to do the work of reading, in this sense, I have to top the book. I have to conjure the scene, come up with my own pictures, my own connections and directions. The movies offer more infantile pleasures. Huddled in the dark, I can become the bottom even the most sterling top longs to become. Take me, I’m yours. But in this taking, this occupation, this possession, I am missing so much of what flashes past. Even though as an artist who makes movies I am forever returning to my computer universe and trying to articulate with precision each and every pictured collision, every archeological layering of sound, when the moment of exhibition finally arrives, much of this will be absent, missing, missed. Though it will unreliably missed, the gaps won’t occur for everyone in the same way. If they did, one would be able to produce feature length movies that would last just a couple of minutes.

Distractions

The man I am sitting beside has fallen asleep and is snoring loudly. How can I concentrate on what you’re telling me when he’s so loud? The chair is uncomfortable, the dinner was too rich, I haven’t been sleeping well lately. Apart from the restless interior monologue that fills every moment, there are other reasons why I can’t pay attention to you. Every occasion is accompanied by distractions, in other words, there’s not just you and me, alone at last, sitting in our white cube universe. My hungry eyes are forever seeking out screen refreshments that will be quickly erased, my ears long to hear new sounds that fade into oblivion nearly instantly. There is no virginity of perception, no airless chamber where we can begin again. Instead, we encounter each other, and our media extensions, in the midst of our own noise, and the noise of our neighbours.

Invisibility

The movie theatre presents the cinema as architecture. The theatre has a fixed screen and fixed viewing lines from fixed seats – the fix is in, the fix is in the house. Or: the fix is the house. Of course, it didn’t begin like this. In its beginnings, cinema was nomadic, projectors were carried in, and screenings were always attached to other events, sideshows, spectacles.

This wandering cinema reappears in the form of broadcast television. From the cinema as architecture to the cinema as furniture. Smaller and now domesticated, the television works to remap the home. It often occupies the “living room,” providing a shape for leisure time encounters. The television aims that room, turning it into a theatre, and turning its inhabitants into an audience. The bedroom is for sleeping and fucking, the kitchen for cooking, the bathroom for cleaning and shitting, and the living room is for watching other people’s pictures.

The mobile computer provides a further elaboration of the nomadic screen as an agent of post-capital globalism. Wireless connectivity extends the reach of screen culture into every aspect of waking life, even as traditional storytelling structures (like movies, yes, even avant movies) give way to archival retrieval.

Each movie exhibition mode offers its own distractions. Let’s call them: conditions of invisibility. Each staging formula for movies offers its own particular ways to make what is on display hard to see. At this moment movies are being shown in a fantastical variety of circumstances: in laundromats and bars, in living rooms and cell phones and airplanes and art galleries. Let’s look at a couple of ways movies are being shown, and see how the frame works to obscure the picture.

Movie Festivals

Most artist’s work shows at movie festivals, or the internet, or in art galleries. At a movie festival, one program is shown after another, so that it’s very difficult to hold on to the strong impressions of one screening, before another is already underway. Think gluttony at a smorgasbord. Think pie-eating contests with a starter pistol and barf buckets beside each contestant. This blurry overlap of pictures works to create invisibility.

Inside each program there are often clusters of shorts, one playing immediately after another. The too-muchness of a present moment is multiplied by the too-muchness contained within a single program. Unless you’re Peter Kubelka, and you insist on showing your new short movie ten times in a row. But for most of us, not yet sainted, we are happy enough to have our short hopes chosen and then sausage-linked to create a program. Here is a primary agent of invisibility. “Programmers” often work by seeing vast quantities of work in a short period of time (they are the primal scene of specialist gluttony which the festival patron or fan is invited to repeat), and then select programs in the afterburn haze according to “themes.” These thematic groupings are ideal for producing invisibility, working as they do to emphasize certain features of a work (close-ups of hands, for instance, or the injustices of disposed Palestinians), while at the same time de-emphasizing (or making invisible) certain other aspects.

Another common strategy (call it: the thinking of non-thinking) is to group works according to genre. All the story movies belong in one program, all the animations in another. Once again, this produces a maximal possibility of invisibility. Placing a short animation between, for instance, a documentary-inclined short and an experimentalist effort, might allow each of these movies to appear via contrast and juxtaposition. What is emphasized in this approach is not the way that these works appear similar, but how each is unique and particular.

The “programmer” typically works as a kind of meta-filmmaker, re-aligning the rhythms and intensities of individual works in order to produce a new movie, made in parts, re-authored by the programmer. Perhaps it should come as little surprise that programmers should posit themselves as artists, and that this should have become the most common form of short motion picture exhibition. It is assumed that if someone sees a great number of movies, they are similarly qualified to group movies together. But as we have seen, in festival after festival, this is not the case. Most of the time, the way that movies are grouped together work to make them invisible. Why? Because “programmers” work from an accounting model of timekeeping. There are ten slots in the festival. Each slot is a program. Each program has a name. The task is to fit the chosen movies into the available slots. The “programmer” begins with the abstraction of the time table, the schedule, and works to fill time. This method has nothing to do with how one might make a work visible. Instead of timekeeping, the “programmer” might ask: how can I present this work, this individual movie, so that something of its singularity could be recovered by its viewers? This is based on the assumption that the festival is not simply showing the same film, again and again. How can the uniqueness of each movie be addressed? What might be done to offer those qualities to an audience?

What I am suggesting is a reversal from the usual priorities. The general trends, as always, favour the administrator, the bureaucrat, the system. At the movie festival, the initial contact often occurs when the artist fills out a festival application form (already the artist is reconceived as a bureaucrat, as someone who spends their lives filling out forms, following the rules, trying to become part of a system that is busily reshaping everyone in it). Many festivals have special log in names, email addresses are added to promotion lists, databases are created, information is martialled and systematized. Once a movie has been accepted, it is already understood and received as part of a system, as a motion picture experience that has to be slotted, that has to “fit.” How many times have I heard “Oh, we loved Movie X, but we couldn’t run it because it didn’t fit.” The paternalistic attitude in general display amongst the kind and hugely hard-working folks that make up the micro-verse of short movie programmers, offers up a litter of motion picture debris for my already distracted attentions. Instead of beginning with the actual qualities of the work, they begin with their abstract notion of programs which need to be filled. I believe that if they started from the other end, the possibility of making work visible would be greatly increased.

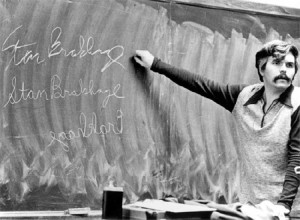

Stan Brakhage

I was happy to sit at least a dozen times while Stan presented his movies. Before they began he would stand at the head of the room and begin talking about how the small piece of masking tape at the end of a roll of film was destroying the American avant-garde, or about what it meant to look at something for the first time. He talked and talked, and as the years went on, and he worked increasingly with very short, hand-painted movies, he would play just a couple, and then the lights would come on and he would talk again. He was generous and smart and filled with insights, but more important than all that, I realized later, was that he was working to defeat the invisibility his work invited. His movies were so difficult, often abstract and silent, and filled with the idiosyncratic rhythms of a body singing its singularity, so he needed to get us up on the edge of our chairs so that we could try as hard as possible to see what was actually projected on screen. His introductory addresses were a way of trying to big up the attention in the room. It was a feat he managed better than anyone I have ever seen. If the same program had shown, in the same order, but without the filmmaker present, much of that work would have lapsed into invisibility. At least for me.

Foreplay

The space before a screening begins is an interstitial space, an in-between place. It was a space used to great advantage by Stan Brakhage, Barbara Hammer, and many others, to make their upcoming work visible. Most festivals, on the other hand, use this space to remind people to turn off their cell phones, or to advertise other parts of their festival. If the aim of a festival is to make the work they are exhibiting visible, this is not particularly helpful. The commonplace says: works “speak for themselves.” And besides, the “programmer” is usually busy tending to some crisis in another part of the building, some vital piece of equipment is refusing to talk, an important guest is melting down in the lobby, there’s bathroom vomit that needs to be cleaned up pronto.

Why are the histories of those being presented not on offer? Often the artists are present, but festivals don’t quite know what to do with them. Programmers, who can be heard holding forth on obscurities from unnamed cities around the world in the bar after the show, usually don’t manage to say much that is helpful before the program begins. Once again the commonplace says: their work is done. But I believe this is yet another incorrect assumption, which helps to maximize the possibility of invisibility. By failing to take care of its interstitial spaces, the festival conspires with the gravity of inattention and invisibility in order to make the work unseen. The space before and after a screening is a public space of gathering and attention, and can be used not as a promotional vehicle, or the fringe version of advertising (sponsors, etc.), but as a way to forward the project of visible singularities.

Art Gallery

Perhaps it is little surprise that movies have begun showing up in art galleries. After all, an explosion of screen culture has seen movies appear on public billboards and tram stops and mobile phones. Moving pictures are on the move, and at least at this moment, the art world is not immune to this technological imperative. Galleries and museums large and small have committed precious real estate to new screens, and this has caused the predictable anxieties that scarcity and status so often accompany.

A new aristocracy of the motion picture has asserted itself: these artists are the winners of important prizes, feted in biennales, the subject of books and catalogues. And for every king and queen there are legions of the underclass, every visibility is subtended by its inevitable invisibility, particularly those who continue to make small experimentalist pictures which are reserved for the traditionalist safe houses of the avant-garde. The first line of invisibility in the gallery is the radically reduced short list of what can be shown.

But how do art galleries create invisibility for their display items? Each circumstance is individual, of course, but some general lines can be drawn up. Despite its galleried destination, the work shown is often conceived for cinema viewing conditions. In other words, the room should be perfectly dark and perfectly quiet, the sound emanating from quality speakers, the image sharp and bright. Needless to say, these ideals are often left behind. Sound bleeds between installations are frequent, the projectors or monitors range in quality, and specially manufactured cinema screens are usually replaced by white painted walls which absorb, rather than reflect, luminosity and colour. While much work aspires to or secretly requires the conditions of cinema, it lands instead in a situation filled with unwanted ambiences, whether from other installations, gallery staff, visitors, exterior hallways and streets, or light coming in from the windows. Even from the outset, then, part of the work is “missing.”

There is also the question of duration. In the cinema, specified viewing times are divided into programs whose lengths are specified. Beginning and end times are clearly denoted. In the gallery, the viewer is invited to arrive anytime during gallery hours, a considerable luxury, affording, at least potentially, much greater access. Having work run again and again is a way of defeating invisibility, because the restricted time zone of an isolated screening has been exploded to fill the available time of a gallery’s open doors. But often galleries are showing more than a single work, so the promise of something more is a constant lure (often accompanied by muffled and beckoning soundtracks). And galleries may be located in an area of the city where a number of other galleries are similarly situated, all open during the same hours, inviting viewers to browse from one to the other, like shoppers in a mall. The promise of something else, close by, is another way the gallery produces invisibility.

The absence of comfortable seating is another commonplace in galleries, never mind that they are showing works that are hours long, some white cube hangover requires the banishing of furniture, or at most a throw cushion gesture in the direction of possible viewers. Perhaps it is imagined that motion picture installations are only for well-toned teenagers, with their inflatable sneakers, able to stand at attention for hours on end.

While the average time each gallery viewer dedicates to a single piece of work remains just a few seconds, most motion picture installations far exceed this length. Some roll on for hours. How long do I need to sit and watch Douglas Gordon’s 24 Hour Psycho before I can assure myself that I’ve really seen it? Or is the point of this mistitled work (its running time is closer to 18 hours) that it can never be entirely visible? What about Ulrike Ottinger’s eight hour Taiga installed at the Witte De Witt Gallery in Rotterdam? Were viewers really expected to sit and watch this slow-moving masterpiece in a gallery, surrounded by ambient light and the constant shuffling of visitors attending to those parts of her retrospective that required shorter attention spans? Whenever I visited, the space dedicated to this work was always empty. Without any hope of reaching the end, why even begin?

Second Encounter

In her witful address at the International Experimental Media Congress in Toronto (April 2010), Austrian video artist Hito Steyerl remarked that sub-optimal projection conditions rendered many motion picture installations incomplete. She posed this question: what do the missing parts create? Her answer: a desire to complete. She suggested that a distracted and circulating multitude plus dysfunctional tech produced a lack of attention. In a word: invisibility.

The low visibility motion picture zones of many art galleries, Hito continued, are a call for a different kind of attention. What is on show often exceeds the grasp or attention possibilities of any individual spectator. The Ottinger movie, for instance, appeared as a kind of archive, offering up weddings and blacksmiths, food rites and hunters. In the cinema, this work would be more likely received as a cluster of narrative trajectories. Perhaps the “desire to complete” the experience of this movie in a gallery would come not from a newly mobile spectator, but from a newly mobile collectivity. A temporary collectivity perhaps, sharing fragments, offering views which would be both partial and personal. When would this group meet? Presumably only after seeing the exhibition, or parts of the exhibition, because it is the exhibition that provides a common ground for the group, even though each attends to it in their own way. Hito named this meeting: a second encounter. And what the second encounter might make possible, is that a work which was invisible, or at least partially obscured, might become visible. Perhaps it would be possible to see movies after they’re finished, after the screening time is over.

The feeling that there’s too much to see is also a call for a new form of collectivity, a post-audience audience, no longer mute witnesses to spectacle, but agents in a collective formation of social understandings. The example that Hito provided was clear enough: she had come to a gallery as an instructor of a class. When the show was finished, the group, already formed, re-gathered to speak about their experiences. How else might the second encounter occur? How could galleries, or for that matter, movie festivals, work to produce the conditions that would make a second encounter possible?

The Form of the Second Encounter

Even in the specialist scrums that attend fringe movie events, post-screening chatter rarely touches on the work shown only moments before. I like it, I don’t like it. Thumbs up, forefingers down, middle fingers raised, that’s about it. The issues and questions raised around the work quickly become party chatter backdrop, as more pressing gossip requirements are fulfilled. Perhaps it’s just me. But I believe the second encounter requires something more formal than inviting a scare of smart people into a room. Some kind of shaping device is required.

The form of the movie theatre is very exacting and precise. The mechanisms of projection, the requisite darkness, the social contract of collective silence – all these are parts of a strict code that permit a viewing of movies that is both collective and individual (this oscillating current, it seems to me, is at the very heart of fringe practice). The second encounter surely doesn’t need to be as strict in its codings as this, but it can’t be a free-for-all either. A classroom discussion that doesn’t take place in the classroom seems to be one way to fulfill the requirements of a form that should be neither too tight or too loose. How to grant form to a second encounter? This question might be a useful tool for institutions to think through the issue of invisibility, how their own individual framing devices (their specific architectures and technologies) work to produce invisibility. And how each and every circumstance carries the seed, before and after screenings, for second, third and fourth encounters, which could produce new visibilities, new qualities of attention, new formations and new publics.