Title: Aftermath

Prelude

intertitles 00:42

The city is a museum.

There are four exhibits here.

The lives of four artists.

They left marks

on the bodies of those left behind.

Part one: Fats

2:20 voice-over

The first time he ever got a hundred dollar bill Al Capone gave it to him. Now it’s a funny thing how that happened.

My father was playing in Chicago. Al Capone lived in a suburb of Chicago called Joliet, Illinois. He was playing in a show one night at the Sherman Hotel. One night they pulled up in a car the guys come up to him and said, “C’mon Fats we want to take you somewhere.” “What?” They pulled a gun on him and told him, “C’mon.” So my father was trying to think, “What the hell… Whose wife am I going out with now that somebody’s going to do this to me?” He didn’t know what the hell the problem was, right? They took him on, blindfolded him, took him some place, took the blindfold off, sat him down and Al Capone said, “C’mon play for us Fats.” And whenever they asked him to play a tune they stuck a hundred dollars in his pocket. They kept him a day and a half, when he left all his pockets were full of hundred dollar bills.

4:50 intertitles

He was born in May 1904

one of 12 kids, only 5 survived.

He was kicks.

His mother Adeline had diabetes.

She dropped dead of a heart attack at 50.

She was so large

her body didn’t fit through the front door.

Her corpse was lowered out the window

with a block and tackle.

Fats vowed never to set foot in the house again.

He was sixteen years old.

7:33 voice-over

Every time I saw my father in the summer it was one big party. One party after another. When my father was in a show, for instance he played in the Royal Theatre in Baltimore, these were the theatre circuits, they did five shows a day. They start at 10 in the morning and don’t stop until 2 o’clock at night. You go into my father’s dressing room there’d be 30 people deep in a room that would only hold 10 people comfortably. Bottles, drinking, “Hey Fats.” He could hardly get in there himself. He’d be like that all day long.

8:20 voice-over

voice-over: If I’d drink as much as him I’d be dead. When I first met him in Cinncinnati, he’d go to work and take a gallon jug of whiskey, bootleg whiskey, and set it down by the piano, and by the time the night had gone that bottle would be empty and he would be still like he’d never had a drink.

9:10 intertitles

Harlem was designed as a white suburb

but the real estate bubble burst

anxious landlords began selling to blacks.

9:58 Ta-Nehisi Coates voice-over

I think our criminal justice system is working as intended. It is only broken to the extent that our society is broken.

If your intention is to jail massive numbers of people, if you believe that prison is an effective means of dealing with the myriad social needs of the African-American community then it’s pretty effective. In fact there’s a long history in this country of dealing with problems in the African-Americn community through the criminal justice system, criminalizing social problems in a way we don’t do in other communities.

For instance, if you looked at the research you would find that 60-70% of people in prisons are suffering some sort of mental health problem. Upwards of 50% go in there dealing with some sort of chemical dependency. Viewed from another lens these are public health problems.

11:20 voice-over

So today I’m going to show you how to play stride piano. We’re going to use this song Ain’t Misbehaving as a demonstration piece. There’s some very common methods of sounding like an authentic stride pianist.

11:50 intertitles

Cold empty bed

springs hard as lead.

Pains in my head

wished I was dead.

What did I do

to be so black and blue?

Even the mouse

ran from my house.

They laugh at you

and scorn you too.

What did I do

to be so black and blue?

I’m white

inside

that don’t help my case.

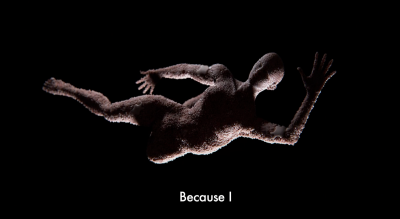

Because I

can’t hide

what is in my face.

To spite despising.

The first Broadway protest song

against racism

was written by Fats Waller

and performed often by Louis Armstrong.

How will it end

ain’t got a friend

my only sin

is in my skin.

What did I do

to be so black and blue?

14:31 voice-over

He started doing big things. Then he went into pictures. He couldn’t have any kind of stature so they wanted him to be a shoeshine boy. My father said he would not play a shoeshine boy, he didn’t give a damn what they did. Then they turned around and said, how about an elevator boy? He said OK I’ll play an elevator boy. When I stop to think about that, he got them to give in just a little bit, but what’s the difference between an elevator boy and a shoeshine boy? It’s not any different except that my father wasn’t going to give all the way down.

15:13 sync sound elevator scene

Fats Waller: Mr. Bolden I’m the one that sure delighted to see you back.

Mr. Bolden: Thanks Ben you’re looking fine.

Fats Waller: I hate to bother you boss but I thought you could find a spot for me in your new show.

Mr. Bolden: You take a tip from me Ben. Your spot is right here in this elevator.

Fats Waller: Thank you sir. Thank you sir.

15:28 voice-over

A lot of times I hear especially black people talk about: why did those people in those days act like that? But that’s the only way they could make it in pictures. They didn’t have any money to make pictures, white people had the money, so people had to go along. The dues they had to pay. Mantan Moreland, all these old stars. They call them handkerchief heads, but that’s the only way they could get in. Once they got in they tried to make it a little better. It’s people like my father, Mantan Moreland, Willie Best made it possible for people to do what they’re doing today. You got to pay your dues.

16:03 voice-over

He just had a job, he was glad to have it, to be a token. I’d like to be a token now, someplace because that’s all you’re ever going to get.

16:20 voice-over

There were always black guys just couldn’t work because they weren’t accepted there. In Chicago, in the 40s and 50s, there were certain places downtown that never had a black entertainer or musician, they weren’t hired.

16:55 voice-over

In southern towns we stayed with private families because there was no hotels for us. Some towns had a little black hotel but most of us stayed with private families. WIth Cab Calloway we had a Pullman train, we used to go on all our one-nighters through the South on a Pullman. Pull the train into town, play the dance, get back on the train and pull us out the next day to the next town.

17:38 voice-over

My father played what they called the southern circuit. When you went down to the south they had a line down the middle and whites would be on one side and black on the other. They would listen to the same music but they couldn’t intermingle. That was one bad thing. They would still intermingle, but they’d do it slick, you wouldn’t be out in public. My father didn’t play the southern circuit too often for that reason. He didn’t like it.

18:08 voice-over

The next number is called What Did I Do, To Be So Black and Blue?

intertitles 18:38

He could set the telephone book to music.

They called him the king of Harlem.

Fats + Louis Armstrong + Edith Wilson

1000 pounds of rhythm.

Critic Dick Wellstood wrote

It’s so hard to tell what Fats could do

because he was always trying to entertain.

20:25 sign

Here every night. “Fats Waller” and the Beale Street Boys.

20:48 sync sound

waiter: The boys want another round.

singer: Give them a joint, it’s on its last legs anyway.

waiter: Two up boy.

singer: Baby baby, what is the matter with you?

Fats Waller: Ain’t nothing wrong with me babes. Nothing at all.

singer: Baby baby, what is the matter with you?

Fats Waller: One never knows, do one?

singer: You’ve got the world in a jug

Fats Waller: Yeah, but where the stopper?

singer: and you’ve got nothing to do.

Fats Waller: You hear that mess? She’s always laying it on me.

singer: I went to a fortune teller and had my fortune told

Fats Waller: What did she say?

singer: She said you didn’t love me, all you wanted was my gold.

Fats Waller: She was right, how’d she know?

singer: It ain’t right.

Fats Waller: Everybody wants some gold baby.

singer: Takin’ all my money, goin’ out having yourself a ball.

Fats Waller: Suffer excess baggage, suffer.

Part two: Jackson Pollock 22:30

23:00 voice over

I go to work every day. Just like any other worker.

23:15 voice-over

My instinct about painting says, ‘If you don’t think about it, it’s right.’ As soon as you have to decide and choose, it’s wrong.

23:55 voice-over

Painting is either plagiarism or revolution.

24:30 voice-over

It’s easy when you don’t know how, but very difficult when you do.

25:50 voice-over

All children are artists. The problem is how to stay an artist once you’ve grown up.

26:15 voice-over

Art, like morality, consists in drawing a line somewhere.

26:40 voice-over

My father once said, ‘You don’t have to reinvent the wheel.’ But I think you do, maybe not every day, but pretty often.

27:03 voice-over

In 1936 Dali spoke at the International Surreal Exhibition wearing a diving suit. He forgot to attach an oxygen tank to the suit which he bolted shut. The audience reacted enthusiastically to his impression of a man choking to death, before someone raced onstage and saved his life

27:57 voice-over

OK, how about this? Let’s tell young people the best books are yet to written; the best painting, the best government, the best of everything is yet to be done by them.

28:22 voice-over

Being an artist means feeling crummy before everybody else feels crummy.

29:04 voice-over

Painting allows me to find myself and lose myself at the same time.

29:44 voice-over

I do more painting when I’m not painting.

30:10 voice-over

My brushstrokes are no better than many other painters, But the pauses between the notes.

30:45 voice-over

I moved out here with Lee about two years ago. It’s been two years since I had a drink.

But tonight, as soon as the filmmakers leave, I’m going to open a bottle of bourbon, and I’m not going to stop opening it.

Five years later, I’m going drive my car off the road and die. I’ll be 44 years old.

31:31 voice-over

Every picture has a hidden cost, a private life, a secret. At least, if it’s any good.

31:42 voice-over

People come because they want to know the secret, without understanding that they themselves are the mystery.

31:57

My audience. My killer.

Part three: Rehearsals

33:15 voice-over

A year ago, I nearly died of pneumonia.

I felt myself stepping into the white light, when a hand touched my shoulder, and told me I had to go back.

Reluctantly, I turned to face the body that was lying on the bed.

The body that looked so much like me.

34:09 voice-over

I decided to start a series of photographs called Rehearsals.

34:28 voice-over

I started to use myself in the work because this body doesn’t really belong to me. Sometimes it feels like I should put it back in the lost and found.

34:54 voice-over

I think of my body as a disguise.

36:35 voice-over

I would run away from my foster parents, and spend a lot of time sitting under an old elm tree. That elm tree became my parents. At night they taught me songs.

37:20 voice-over

I tried to give my body to anyone who asked for it.

You know, it was like a civic duty.

37:43 voice-over

It seemed to give people so much pleasure,

I wondered why it couldn’t bring me more pleasure.

38:17 voice-over

Mostly when I meet people I can’t remember their face or their name. But when I remember a face it starts to live inside me. It’s as if I’ve swallowed a telephone directory just for one person. Even if I don’t see them I’ll get the news, sometimes about things that happened in their past and sometimes things that are going to happen later, in the future. I need to go to a quiet room and be dead for a while just so I can feel something.

39:46 voice-over

When I was 25 I fell in love with a tree and even though it smelt good and was never judgmental and I was happy, my doctor said it was wrong. She said: you’re an animal. Try looking at yourself in the mirror. Like an animal.

42:01 voice-over

What does it mean to make pictures in a time of exterminations and extinctions?

43:12 voice-over

What if human nature was a relationship between species?

A dog that refuses food is also making pictures of dying.

The candles are also a picture of dying.

45:02 voice-over

There are so many ways that a woman tries to avoid being a monster.

As if she were already dead.

45:47 voice-over

I used to die alone,

now I’m dying with the old buildings.

Together we’re making a compost for the new world.

46:56 voice-over

All of my friends came to my funeral, I was so happy. I taught them how to die, how to leave behind everything they knew, but when they couldn’t recognize themselves anymore, they blamed me.

Later that night I held an atlas in my lap, ran my fingers across the whole world, and asked: where does it hurt?

Part four: Frida

51:19 intertitles

Today as never before

I am a Communist being.

I have digested the history of my country.

I know the class conflicts and economics.

I am one cell of the revolutionary mechanism.

The revolution is a struggle of forms

and liberation.

53:35 intertitles

The struggle of the two Fridas

one dead, one alive.

I was the only painter

to give birth to myself.

Many came to console me

only to find themselves consoled.

One year in hospital

the wound is not closing.

One year in hospital

I know that if I was ill enough

my husband Diego would come.

He was never mine

He belonged only to himself.

German assassins fire two shots into Diego’s studio

aimed at me

but I have been replaced.

Diego is away

having an affair with my sister Cristina.

56:18 intertitles

Every wound gives off its own light.

I was not born beautiful

I created it out of necessity

as a shield.

58:56 intertitles

In 1925 a train ran through a bus

a steel pole entered my left side

came out through my vagina.

I lost my virginity.

59:27 intertitles

The doctors put me together like a photomontage.

59:43 intertitles

I was in bed for a year.

The voyeur of my own emotions.

1:00:04 intertitles

After the accident

everything slowed down

and I began to paint.

1:00:33 intertitles

Diego was not a nice guy

but he knew how to look like one.

1:01:14 intertitles:

Diego’s ex-mistress came to the wedding

she lifted my dress and said

You see those two sticks!

Those are the legs that Diego has instead of mine.

1:01:54 intertitles

The accident made me beautiful

Diego made me ugly

I needed both.

1:02:17 intertitles

I had a third abortion, appendix removed, foot surgery.

Diego: The more I loved her

the more I wanted to hurt her.

1:04:04 intertitles

Doctors make 28 corsets

one made of steel, three of leather

the rest in plaster.

1:04:43 intertitles

In 1953, my first solo exhibition in Mexico

they performed a bone transplant the night of the opening

all of crippled Mexico came to give me a kiss.

1:07:20 intertitles

Fighting with images as ammunition

for the first time my painting becomes

a living part of the class war.

1:07:50 intertitles

I painted only the essential, the necessary

I didn’t have time for the rest.

1:10:19 intertitles

My affair with Trotsky

the revolution had not made him

a better lover.

1:12:41 intertitles

And here is where I end

though I will always continue

writing to you with my eyes.

1:13:08 intertitles

I hope the exit is joyful