Silent Songs: an interview with Elida Schogt (2013)

Mike: Your earliest work in film seemed already fully formed, and arrived as a trilogy of personal Holocaust tales, strained through the family. Can you talk about what led you to pick up the camera and begin?

Elida: It’s interesting you say the trilogy was fully formed. The three short films, only thirty minutes altogether, actually took over five years to make. There was a lot of research, writing, stumbling in the dark (literally and figuratively), as well as trial and error before the three works emerged. I didn’t so much pick up the camera as start piecing bits together under the lens.

It was in the mid-nineties that I first saw short, independently produced, experimental films. Before that, I didn’t even know such a thing existed; nor would I have been able to conceive of making my own work. Somehow by watching these strange, intriguing, little films, the idea of my own practice started to become a possibility. Seeing small films projected on the big screen, offered this great parallel to the “I’m small, my story’s big” push-pull I was feeling. Watching the work and meeting filmmakers, I saw how directly a film can be an extension of a person. Also, how the films communicate with others. Pulses of light, words, silence.

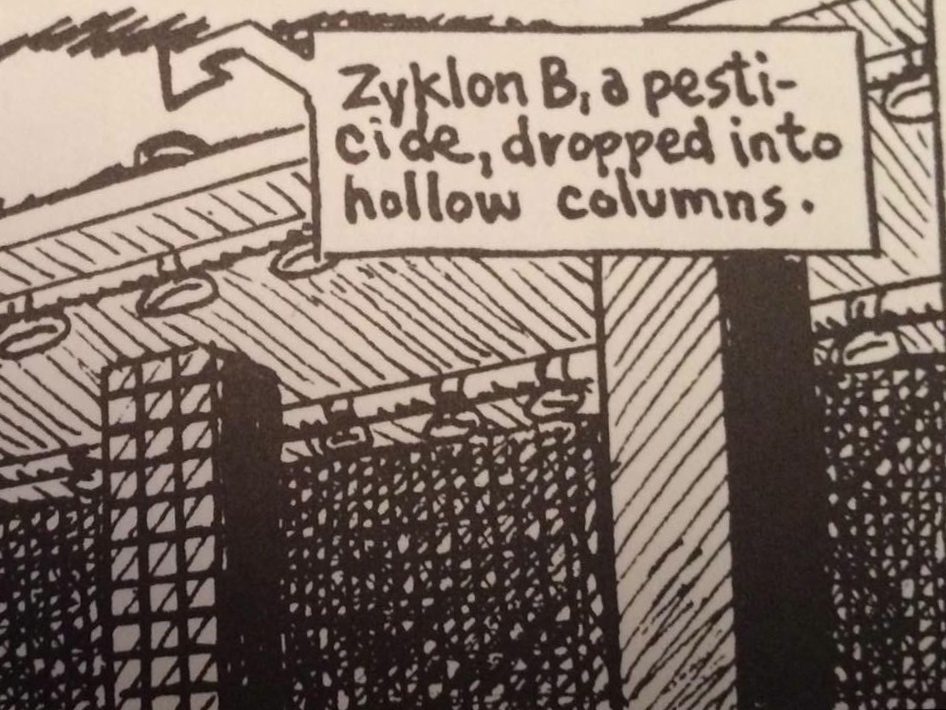

Already interested in my family history, I started reading Maus, Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel about the Holocaust. It was there that the hand-scrawled text in one of the character’s speech bubbles hit me: Zyklon B. I thought, “Zyklon B! That’s the stuff that killed my grandparents!” There was a shock in the realization that something so specific and identifiable had killed them. Growing up, there had been such a heavy, palpable silence around the subject of my grandparents that it had never occurred to me to think of such details. “Who actually killed them with this?” was my next thought. The Nazis, of course. But who specifically? Who had made this stuff? Who had turned it into the gas used in the death camps? What was the name of the person who was directly responsible for my grandparents’ deaths?

It wasn’t so much a question of picking up a camera as following several paths to the scene of the crime. I never went to Auschwitz while making the film. That fact probably works for the benefit of the project. It’s a film about the space between here and there, between then and now. Not a piece about the death camp. In any case, it wound up being a film in part because I was working in the independent film scene in Toronto as interim Executive Director of the Images Festival at the time. I was seeing a lot of work. In fact, that year, we did a retrospective on your work, Mike. I think that somehow you and your work may have played a part in getting me started. Seeing a local person creating films made the idea more feasible. That’s how this personal investigation collided with the idea of making a film.

Mike: I want to ask you about family ghosts, phantoms, hauntings. Your grandparents died long before you were born, but I’m wondering if you feel they hold some of your truth, or that they held out a promise for you, an appointment waylaid by the Nazi genocide. Another way of asking this might be: why make a movie about your grandparents?

Elida: What a complex question. Where do I begin? Why make a film about my grandparents? Because of how they died. The way their story ended. They were only two amongst millions, so their fate is not unique. But from my perspective, they are my mother’s parents and they were murdered. That’s shocking. So, it’s not that my grandparents held my truth. It’s that their story, the way they were killed, is fundamental to my mother’s story. This film is about how her story becomes my story.

When I set out to make Zyklon Portrait, while it was an elegy for my grandparents, it wasn’t ever meant to be strictly about them. I do refer to both my grandparents in the film, but I primarily focus on three generations of women. My exploration is about my mother’s relationship with her mother, and my mother’s relationship with me.

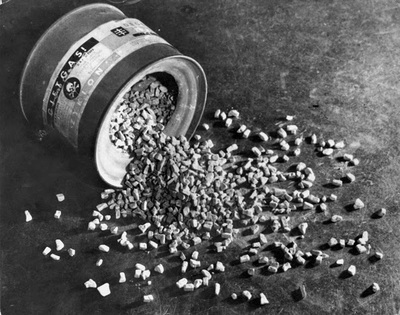

In the promotional material for Zyklon Portrait I describe the film as “a Holocaust film without Holocaust imagery.” The film neither contains explicit archival images of the concentration camp prisoners in their striped uniforms, nor of the victims’ corpses. The photographs that I sourced from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum archives and used in the film all showed Zyklon B gas canisters. By juxtaposing these stills with photographs from my mother’s childhood albums, recuperated after the war, the film creates a family portrait inextricably linked to the deadly chemical. In Zyklon Portrait’s “family album,” a close-up photograph of the Kommandant of Auschwitz on trial is followed by a close-up of my grandmother at the beach; my child mother sitting in a doorway looking up at her mother is followed by footage of the showers at a public pool in Toronto — a stand-in for the showers at the death camp. In this way, my present-day surroundings become the imagery used to represent the gas chamber.

What is off-putting in this film is the contrast between the personal perspective and the cold, clinical Nazi point of view. Looking for footage at the National Archives in Ottawa, early on in the process, I came across a strangely compelling 1950s instructional film on how to control corn crop infestation with insects. As soon as I saw the black and white footage of two insects battling it out under a spotlight, I felt like it was already part of the film I was making. At that stage, I pictured the entire film being made up of this insect footage. In the end, it was just one of many strands. Cutting between the insect footage and my mother’s family album pictures helped drive home the mind-set of the Nazi Kommandant. Rather than portray him as a ruthless killer, I contrasted dehumanizing and humanizing imagery to show a more subtle psychological process at work. It wasn’t as if the man was some raging lunatic. Nor was he just blindly doing his job. He had to think of his target as radically different from himself and his loved ones, so he could systematically carry out the killing. To transcend this clinical analysis of the Nazi genocide process, I added a layer of what I called magic-realism. Bridging the macro shots of insects, perfunctory archival stills of Zyklon B canisters and the conventional family vacation photos, is newly shot footage of me swimming underwater; bright-blue, hand-painted sections; and pulses of light made by bleaching black leader. Whether it was the intense blue colour, the sudden movement after a series of stills, or the messiness of the paint on the film, my intruding energy, side-by-side with the black and white world of insects, family photos and archival pictures helped create a charge that jumped across the edits, putting the past into conversation with the present.

How can we show what isn’t here anymore? Holocaust films play a distinct role in the many forms of Holocaust representation. The monument marks a commemorative site just as a grave marks where the deceased is laid to rest. Films may portray a specific place, and are experienced by an audience in a specific locality, but they are seldom attached to that place. It is not the form of a film, but its narrative content that serves a commemorative function. Claude Lanzmann’s 1986 documentary, Shoah, has been described as a film of absence because no historical footage is used. Instead, we see the camps overgrown with vegetation, while the train tracks leading to them remain as material records of the death traffic. The film travels to the present day locations of the annihilation, but what remains absent is the annihilation itself. Shoah’s use of absent images reaches its climax in the scene when Jan Karski, the former courier of the Polish government in exile, refuses to remember and literally walks out of the frame, leaving the spectators to imagine what horrors might remain unbearably vivid after forty years. How can we look at this empty chair and not think of the absence of European Jewry after the war?

While Lanzmann worked with present-day survivor testimony in Shoah, Zyklon Portrait deliberately gives the “voice of God” narration to the Kommandant of Auschwitz. In BBC English, with a German cadence, the voice begins as an instructive guide on how the pesticide was transformed into a genocidal weapon by the Nazis. But after a title card reveals the name Höss, the voice becomes the embodiment of the Kommandant. In addition to this shift in the dominant male narrator, my mother’s halting recollection of her childhood, relayed through her often-faltering voice, offers a counterpoint. Silence is also deliberately used throughout the film to break the central voice-over. The overarching narrative of the film speaks to the general absence of the female perspective within the dominant structures of storytelling, as well as the specific absence of the female voice in traditional documentaries.

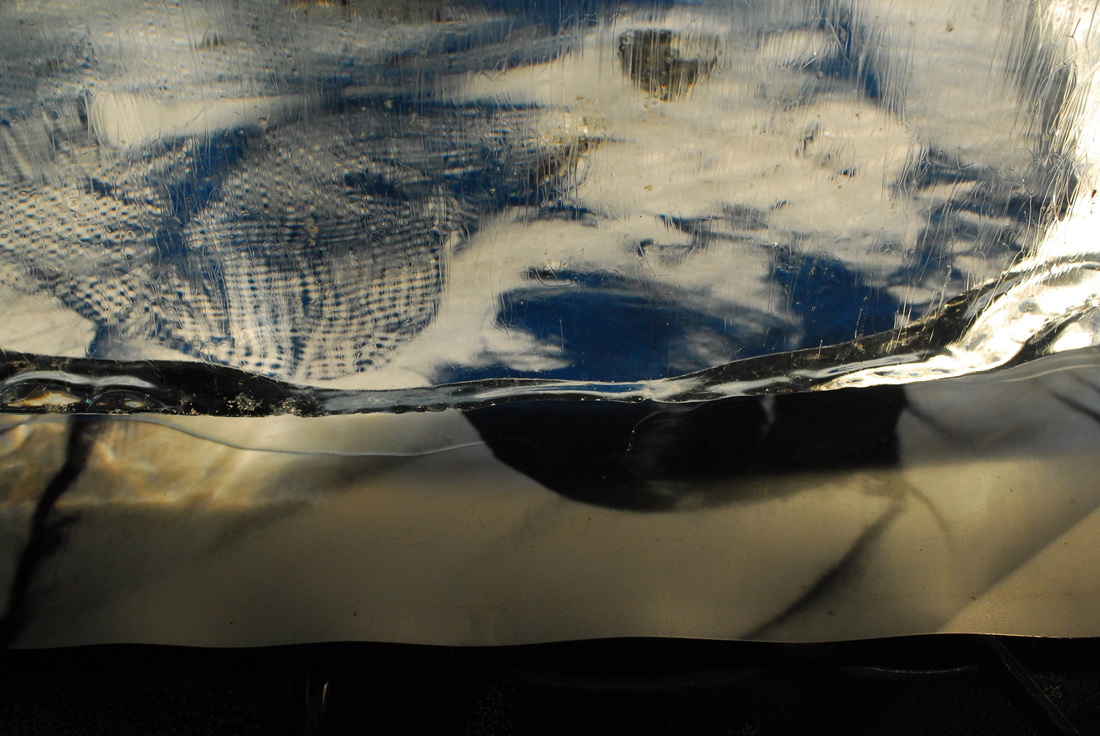

From its opening sequence of a female swimmer beneath a sunlit liquid surface, the film opposes the life-sustaining presence of hydrogen in water and the body with that of the hydrogen cyanide pellets transformed by the Nazis into the genocide gas “shower.” Throughout the film, water signals the continuity between the materiality of life and a pervasive, subconscious pull. The cumulative effect of all the water imagery creates a sense of interconnectedness between the human body, oceans and weather systems; but also between bathtub water, swimming pools and the manufactured chemical weapon Zyklon B. Water blurs the boundaries between mother and daughter, self and other, now and then.

As Zyklon Portrait draws to a close, ghost-like blotches flicker across the screen — the removal of emulsion with bleach from the black celluloid leader creates intermittent darkness and light. In reflecting on the question that refusing to show the gas chambers means avoiding the Holocaust, the chemical disintegrations of the film body returns us to the question of what is missing. As much as this imagery was my attempt at finding a representation of the “nerve centre” of the genocide, it is also part of the psychodynamic space between mother and daughter. Towards the end of the film, my mother says “Those last moments, you do not want to visualize.” The screen goes black. Soon after, the same sunlit pool water with which the film began again fills the entire frame. The closing words are spoken:

DAUGHTER: This is the first time that we’ve discussed things like this. And, I don’t know why I was so drawn to that particular side of things.

MOTHER: That’s all right, because that’s your way of looking at it. Everybody has their own way of going back to what really happened.

This exchange, recorded at my parents’ house, marks an important moment between my mother and me. I chose my mother’s words to end the film, because despite her earlier reservations about my focusing on the specificity of Zyklon B and the gas chamber, she seems to come around. I gain her approval (and her love).

Mike: Before we plunge into the other two movies in the trilogy I’m wondering if you could spare some words about Liquid State — which also touches on childhood, memory and family history.

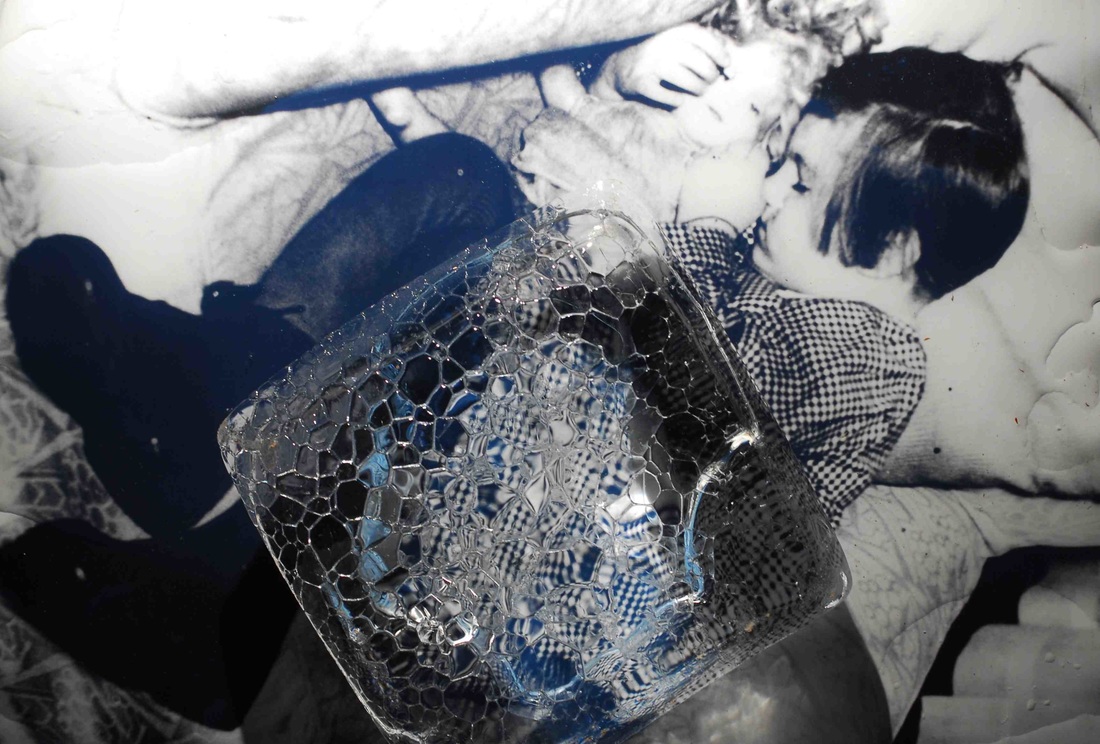

Elida: Liquid State consists of three ice blocks (39” x 19” x 10”) that slowly melt over copies of archival images from the United States Holocaust Memorial Archives. The rectangular ice blocks evoke the work of Donald Judd; but, rather than exploring volume, interval and space in their own right, in my work, the objects are each linked to a specific narrative. One of the three blocks of ice covers an image of a girl who survived, another covers the image of a girl who perished, and the last block has nothing under it. This space is reserved for an imagined melding of the two destinies: sacrifice and survivor guilt subsumed in one place.

As a child, I invented a self that shared Anne Frank’s fate in Bergen Belsen, while at the same time adopting my mother’s survival story as my own. Beyond being one of the most enduring symbols of the Holocaust, Anne Frank was a girl who was a grade or two below my mother at the same elementary school. When I mention this, people often seem incredulous. Anne Frank’s story is epic. But she was also once just a child attending school. The artist statement for my 2006 installation Liquid State reads: “My mother’s trauma of losing her parents in the Holocaust eclipsed my childhood. Growing up, I so strongly and impossibly identified with both victim and survivor that I often imagined sharing both fates — sometimes dying, sometimes living.”

In Liquid State, while the images of the girls could be seen clearly through the ice, it was the process of placing the heavy blocks on the images, then photographing the gradual changes in the ice as the melting took place, and also the work of removing buckets full of water over three consecutive days, that offered me a way to re-enact an embodied process of recovering memories.

Mike: In The Walnut Tree (11 minutes, 2000) your mother offers a concise and affecting account of her family experiences during the Second World War. Forced to flee from her Dutch home because they were Jews, your mother and her two sisters are renamed and each sent to live with different strangers. Their parents are caught by neighbours, sent to two transit camps and then murdered in Auschwitz. You use a handful of family snaps, some home movie moments, and a single cello note. The movie is remarkably efficient, even restrained, as if each element was so precious it needed to be pored over and cherished. How ever did you manage?

Elida: With my first film under my belt, I had a much better idea of what to expect in terms of the process. What I mean to say is that I was more prepared for the many steps along the way. The Walnut Tree emerged because there were so many compelling photographs in my mother’s albums that I wasn’t able to include in Zyklon Portrait. The story of how my grandparents had a number of photographs of their three daughters with them when they fled was the starting point for the film. So, yes, there was definitely a sense that the missing photographs, as well as those that remained, were precious.

While my mother was a reluctant participant in the first project, she was now willingly doing the voice-over for the second film. I had her read a bunch of text that I had written and cobbled together. For instance, Susan Sontag has this great line about photographs being like “portable memories.” Having my Mom say those words with her matter-of-fact tone and clipped, Dutch accent, worked well against the fabric covers of the 1930s photo album covers.

When I was showing Zyklon Portrait in Leipzig, I stole away one afternoon to shoot a train arriving at the station. It didn’t matter that it was a modern train. My heart was pounding as I held the camera. I felt certain I’d wreck the shot. I thought I’d get caught. For me, it seemed that every train still held the relentless motion of the Nazi transports. Even seeing the snow-covered trees through the window while traveling to Ottawa — the ghostlike forest became the route to Theresienstadt.

While I was working on the film, I was back in the Netherlands for a family reunion at my grandparents’ house. My aunt had returned there right after the war and raised her family. She was hosting the event to celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the house. The house my grandparents built.

No matter how momentous the occasion, with so many descendants alive to celebrate, I was happy to have an excuse to break away and get outside with my camera. I pointed the Super 8 up at the branches of the old walnut tree growing in the backyard. It was a typically cold day for May. But atypically for Holland, the sun was shining. Seeing a clear blue sky gave me such relief.

I also shot some super 8 in a field behind the house where we, the Canadian relatives, were staying. It was the cliché Dutch landscape: field, canal and windmill. I stood with the camera pointing to the windmill and then spun around and around. The camera started to bob up and down as I become nauseous from spinning in circles. When I later optically printed this material, the blur and movement worked well with my mother’s halting account of where her parents were hidden in a farmer’s field before they were caught. Throughout the project, I was thinking about stasis and motion — photographs, film and trains. I’m having trouble putting my finger on what it was I was after.

Mike: Perhaps the dizzying spins are part of your project to bring these photos back to life? How often we find ourselves repeating an old emotional lick, like a favourite song we can’t shake. It might seem like we are moving, but we’re actually frozen into caricatures of the freedom we keep refusing. It seems your movie has something to do with surviving these frozen moments of the past. How can we get over these too large to swallow events? Perhaps by going back and re-animating the bits that are stuck, so that they can move forward. I’m wondering if this has something to do with your process as an artist, I mean, the necessity of being stuck, or simply lost. Perhaps that’s an important place for you, a place of inspiration and invention even.

Elida: That makes me think about how often I get stuck in my work. Added to the stasis is the anticipation of how hard it will be to get through it. But finally some motion creates the possibility for change again. The gesture of spinning in circles does seem to embody my approach to making work. Even if I have some sense of what my project might be about, I am often filled with doubt during the process. It can be a very uncomfortable state. This feeling of uncertainty, of being lost, recurrently evolves into a sense of being stuck. Self-doubt. Loss of momentum. Time passes and somehow I find myself spinning and stumbling again. Until… talking to someone, reading something, seeing something, (maybe even doing something), dislodges the “stuckness.” An idea, an image, some text, an action — something propels the work forward again.

I’m in my third year of a PhD in visual arts at York University right now. It’s a studio-based program. That means that for the dissertation we make art. We write a paper as well, but the focus is on making artwork. Somehow, though, I have found myself spinning around the work rather than making it. I have even used the idea of uncertainty as a focal point for the thesis. I have new words for this state — “epistemic uncertainty.” It’s a space conventional academia avoids, but feminist philosophy mobilizes to break down entrenched binaries.

As part of my research, I’ve been filling a 4,800 square foot black box theatre space at the university with fog. The idea evolved out of a paper I wrote on Zyklon Portrait. Alain Resnais’ devastatingly explicit film on the Nazi death camps, Nuit et brouillard (Night and fog) had a huge influence on me. The title comes from the German “Nacht und Nebel,” taken by the Nazis from the magic invisibility helmet in Das Rheingold, the first opera in Wagner’s Ring Cycle. The Nazis used this term even before the Final Solution to the Jewish Question was implemented at the Wannsee conference in January 1942. It was code for getting rid of political prisoners without a trace.

But, for me now, the idea of the fog has evolved into a contemporary space. Not only does the fog signal my own sense of uncertainty, but it also creates a space where others can move about in the unknown. The fog room is not the final artwork, but rather a bridge between what I was doing before and what I will be doing next. What is exciting for me about this process is that my sense of the viewer has shifted from a seated, audience member to an actively engaged participant. The participants’ engagement — their reactions, movements and words — is what creates the space. Now the challenge is to harness the uncertainty (mine that is) and create something more tangible — a video installation — with a group of participants.

Mike: Silent Song (6 minutes, 2001) is the final part of your Holocaust trilogy. It begins with a pair of questions — a framed portrait of a boy’s face and your voice-over: “Why this boy?” And then later: “I keep coming back to this boy because I know something about what has happened to him.” This compulsion to repeat, to see or say again, feels like it lies at the very heart of the project we call cinema, which is founded on the premise of a compulsive repetition, a re-seeing, or at least, a holding and saving up, so that something can be witnessed later.

The pictures in your movie were made by American troops who had arrived to liberate the concentration camp in Dachau. Impossibly, this boy of eleven survived for four years in various camps, until the end of the war came. Your voice-over offers a meditation on pictures — what survives and what doesn’t — and you offer this startling pronouncement: that you hope the movie will outlive you. It was hard not to read this as a kind of death wish, that it would be all right for you to die, now that you had made this film. Let my pictures stand in my place. And difficult as well to mistake the powerful identification you conjure between yourself and the young boy playing his accordion. He is also trying to have his song heard, even in the worst of all possible places.

Elida: Immersing myself for years in Holocaust research and creative work took its toll. I would definitely call that period a difficult time for me. In order to make the work, I read a lot of primary materials. It is indescribably depressing to contemplate the individual acts and psychological experiences of those involved. It seems inconceivable now, but while Rudolph Höss, the Kommandant of Auschwitz, was in captivity, before they executed him, the British asked him to write his autobiography. Parts of this text are adapted for the Zyklon Portrait script. Along with the described minutiae of the killing procedures that I used for my script, Höss also writes lovingly of his family. I also read a number of books by Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi. I remember noting in my journal that Levi killed himself despite his incredible story of survival.

When I came across footage of a young boy playing an accordion on a reel of silent, black and white liberation footage from the death camp at Dachau, I was struck by how incongruous it was to see him sitting there, head tilted towards the sun, while mounds of corpses were being discovered and documented by the liberation troops. The entire reel I had duplicated from the Library of Congress holdings included an image of a Zyklon B canister that I had considered using for the first film. It also showed officials gasping in horror and holding their hands over their faces because of the stench of the corpses.

That brief moment of the boy sitting on a bench, playing his instrument amongst the chaos of the liberation, was what became Silent Song. I couldn’t even begin to imagine what this boy might have seen with those eyes, now blinking in the bright light. To make the piece, I sat staring at the his face for hours, as I first optically slowed down his movements, and then edited the film to have his eyes shut precisely when I say the word: “moment,” in the voice-over. It’s as if both the boy and I are briefly reassured — he about surviving the war, and I about having my film preserved in the archives. But he is surrounded by death, and I cannot help trivializing the value of this little film in relation to all the devastation.

So the idea you point to in your question about repeating, or seeing or saying again through film, is one that definitely plays out in this short piece of mine. The liberation army cameraman films the boy. He also films what surrounds the boy. What the boy has seen. The corpses. But the viewer cannot see what the boy has seen, nor what the cameraman has seen. And yet there remains a sense of repetition of what has come before.

The sheer numbers are numbing to think about. But even within a single family, it remains acutely painful and disturbing. The boy is also my mother. She was never in any of the camps. My mother was hidden with a family in Rotterdam during the war. She was given a new name and could attend school. The family told people that she was a cousin from Hungary staying with them. Anyone could have denounced her and the family at any time. But that didn’t happen. She and her two older sisters, each at different secret locations, all survived. The fact that their parents didn’t survive is a story common to so many people.

It’s hard not to digress. The narrative keeps pulling me away from the more formal aspects of the question you posed. While making Silent Song, I was thinking about the role of archives in housing/storing memories. I was re-reading the bits of Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida that I’d been struck by before. Barthes describes how he shudders looking at a photograph of his mother as a child. She is now dead. He calls his shudder the catastrophe of every photograph. It carries the idea that the person pictured is dead, or on the way to death.

What makes working with photographs and found footage so interesting is the contradiction between what Barthes calls a catastrophe and the fascination, even life force, that comes from seeing images of other people. The person I see before me has died, or will die. But I am alive.

Mike: You were close with Roberto Ariganello (weren’t you?), the fearless director of the local film co-op who died in a swimming accident in 2006 while on an errand to deliver an editing machine in Halifax. He was fourty five years old. Apart from being a tireless advocate for independent movie production, he was also part of a local tribe dedicated to keep film as film alive. Perhaps because these expensive machines required collective ownership and co-operative structures, at least for those without a budget, these old fashioned technologies inspired community formations and chance encounters. Can you spare a few words to remember him by?

Elida: Roberto and I were in a relationship for a couple of years. One of the first times I introduced him to some friends, he talked proudly of his paesano background. He said something like, “I’m from good Italian peasant stock,” and then turned his hands over, palms upward — a testament to the lineage of his working hands.

The idea of working with your hands was part of his filmmaking. He had a kind of plodding, practical approach. His way of preparing the camera was so methodical and deliberate that it seemed to be part of making the film. The way he dusted the lenses or wound the Bolex crank seemed to expand time — the gestures were almost majestic. He did a lot of optical printing and animation during those years. Maybe there was something about the slow, methodical rhythm of the Oxberry camera that suited his inner pace.

I don’t want to make it sound like Roberto was only about the hands-on side of filmmaking. He watched a lot of films, and loved Buñuel for example, and also read a lot. My copy of Barthes’ Camera Lucida used to be his.

Roberto and I went to Cuba together for the Havana Film Festival in 1997. He and his good friend Federico Hidalgo were showing their documentary Loteria. Shot in colour and black and white on both 16mm and Super 8, the film is an experiential audio-visual portrait of Mexico’s lottery. The sound of the child workers calling out the winning numbers is what stays with me most.

That year at the festival there was a spotlight on Cuban filmmaker Santiago Alvarez (1919-1998). It was the first time we had come across his work. Roberto was enthralled. Films like LBJ, criticizing Lyndon B. Johnson, and Now, about the Civil Rights Movement, are two I remember. The films had such an urgency to them, even thirty years later. Every cut felt like a call to action.

When Roberto and I went for a walk one day, we came across a cemetery. Roberto’s eye landed on a child’s tombstone; he read the name aloud “Robertico” (little Roberto). He later went back, camera in hand, to shoot that tombstone. The shot eventually made its way into one of his films. Both of his parents died while he was still in his teens, so this shot was such a sad, sweet way of mourning them. It was almost as if, in that moment, through his camera, he let himself die so he could bring his parents back to life… so that they could mourn him.

Roberto’s death was a huge shock to me. I found unexpected solace in offering a picture I took of him for his website. It shows Roberto sitting on some Mayan ruins, smiling, Bolex in hand.

Mike: In a nearly private camera exercise made last year you offered a glimpse of home life, laying your camera onto various body moments, allowing the lens to breathe in the window views. When the phone rings you respond with an exquisite anger, a reminder of how rare and intimate this emotion is. I’m wondering if you could speak about anger and its motivational role in moving through difficult situations. Would it be too strange to speak of it as a necessary part of an artist’s repertoire, as essential as good framing and a sensitivity to light?

Elida: With the exception of using moments of black, lighting and framing seem inevitable. Is anger? Whether or not anger is intimate and rare is debatable. It is an emotion that can be expressed in so many ways — openly, covertly, towards the self, towards others, individually, collectively… When Zyklon Portrait and The Walnut Tree first aired on CBC in 2001, The Globe and Mail’s John Doyle described the films as “elegantly made works of art, but profoundly angry.” I was really puzzled by the remark. Unaware of my own anger, I didn’t really understand what he meant. But I found myself returning to his words, because something about them rang true. Anger doesn’t always manifest in obvious ways. It doesn’t have to be loud or abrasive. Particularly when you’re also dealing with sadness, the way I was, it can be masked.

I would definitely be interested in working with anger in more deliberate ways as part of my repertoire. Working with and acknowledging anger might be one of the ways to get out of that place of stuckness we talked about. But it would really depend on the piece that I’m working on. Each work has its own nuances, moods and tones.

www.elidaschogt.com