Secrets

The End

Picture it. You are ten years old and newly arrived in a shrug of Montreal’s winterland housing, and the person that is home itself, your mother dearest slugs down the rat poison before staggering out into the backyard where you and she make a last duet together. I can’t go on, not one more day. But before I go, I need to grant you this last gift, this last picture of my dying, the one you will never forget. And then I can say good-bye to this place, knowing I will never leave you.

This is how (or is it?) Arthur describes his mother’s suicide to the other love of his life, Judith Sandiford. She is the girl-woman who speaks in Martin Lavut’s Remembering Arthur (90 minutes 2006), and every time she says the word “Arthur” her face, still improbably young, turns her back into the girl of twenty she was when they met, when he courted her as a twenty-six-year-old menschnik. It is a face that cannot be seen, no matter how often the camera tries to conjure it for us, the forever fresh heartbreak is at once time travel and border guard. What is uncanny in this primal scene recounting is how very different it sounds coming out of the mouth of Arthur’s sister, Marian.

“Our mother died when we were very young, you know that? She was what they call bipolar in those days. Well they do that now. She was manic depressive, that was the term they used in those days and it was obviously a depressive period. She took rat poison and apparently Arthur was there when she did that. Now I wasn’t, I was outside. It’s very odd, you know, when I recall quite vividly the last time I saw my mother. I walked into the house, she was all dressed up. She had her Persian lamb black coat on and a little hat, and my father had his overcoat and his fedora and it looked like they were going shopping. Like that. My father said, ‘We’re going out for a little while.’ ‘OK, bye.’ And that was it, that was the last time I ever saw my mother alive.

Every day I would ask my father how mommy was, and he would say, ‘She’s OK.’ About the fourth day my father took us out for supper. You know we had chopped steak or something. And on the way home – this was in the middle of winter – on the way home, I asked him about mom. Mommy. And he said, ‘Mommy died today.’ Period. We walked further down the street. He never said a word about what was going to happen in the next ten minutes. While we had been gone some ladies took over the house. They were all dressed in black from the top of their heads to their toes, there must have been sixteen, eighteen of them wailing and crying. All of the mirrors were covered. It was one of the most frightening things I’d ever seen in my life. I was seven years old. I looked at them and my eyes just gaped and I took off to my bedroom and shut the door. That was my sanctuary. I didn’t come out. I don’t know what happened to Arthur, whether he did the same thing or not. I imagine he did. But nobody, not a single person – not my father not my auntie, not even some of our family’s closest friends – ever came to talk to us about how sad it was that my mother had died, how we were still loved, and we were going to be taken care of, and everything was going to be ok. It was like we were incidental. We were there and therefore we had to be clothed and fed, but we were incidental to their lives.”

Did their bipolar mother die in the snow as Arthur described? Or was it later, as Marian remembers? Did their mother don her coat and accompany her husband to the hospital where she died several days later? Whose memory are we to believe and does it matter? Witnesses to trauma are notoriously unreliable. But how to resist the impulse as amateur historian, as fringe movie collector, to run fingers back over the years and try to uncover the place where the gap occurs, the absence, the necessary wound that needs to be filled with pictures and sounds? Perhaps it is there, in the memory that is not a memory, and this more-real-for-being-unreal phantom is followed by another kind of haunting. When you get back to your house it no longer belongs to you. Your father is not your father, your life is no longer your life. You are ten years old and your mother has died, and it seems she has taken everything else you ever knew right along with her.

“I remember the first day at school after she died, all the children knew and they avoided me – they were too young for pity, they were afraid. She left a small garden that I kept tending – for her – as if one day she would come back and we could sit there together and I would show her how well her lilies had grown, show her all the new plants I’d added. In the beginning, I was afraid to change anything and it was momentous when I dug the first hole. Then planting became a vocation. Suddenly I felt I could keep on loving her, that I could keep telling her things this way…” (pp. 58-59, The Winter Vault by Anne Michaels, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2009)

Private

Arthur: “Working for the Film Board you’re made to become aware that you’re making films for an audience. They just won’t let you make films that are too excessive, too private. And I’ve always had quite a fight getting each film done. The first film was much easier to understand, it was very popular… but as my films progressed they became harder to understand and harder for me to get money. They couldn’t think of an audience for them.” (Arthur Lipsett Project: A Dot on the Histomap 25:50)

Today it is hard not to imagine “a private film.” Our telephones have been converted to all-purpose media portals that have turned everyone into archivists, photographers, video artists. These once public activities have been repackaged and sold as private commodities, but cinema’s atomization had not yet occurred when Arthur mused about a private movie. Perhaps he was already a citizen of the future? To refashion an industrial art form — with its underpinnings of laboratories and sound specialists and motorized editing machines and expensive European cameras, and imagine that this could be somehow private — this must have been a strange dream in the mid-1960s. Was he already fantasizing about a movie made for the one, a movie that he might spend the rest of his life making that was custom designed so that one other person could see it? And what if that one person was already dead?

In place of the mogul, the studio head, the producer — a lover. Waiting on the other side, with eyes that never stop opening, with ears that hear every whisper, and every space between every whisper. If my movies can’t be seen by everyone, all the time, perhaps they could be seen by someone like you, the one who is always watching me, as if I myself were already cinema.

The Beginning

How does Arthur begin? How does he make the unlikely turn towards becoming a filmmaker? And how not to feel in these beginnings the long shadow cast by his untimely end (or did he time it, exactly, as his last act, a final cut?)? Arthur is another promising student in art school when his teacher is approached by an expanding National Film Board. It’s hard to imagine now, but the Board is reaching out, looking for new roots, searching for bright young things to add a bit of flavour to their art department. Who have you got?

Colin Low: “Now the interview with Arthur was in my office. We spread Arthur’s work out on the drawing table, and the thing that I remember about it, it was mainly models. They seemed to be abstractions. Wooden sculptures. But it was impressive and he was, when he was trying to describe his enthusiasm for what he was doing he was very articulate, clear and straight forward.”

Lipsett: “It was absolutely pure chance that I ended up at the Film Board. I was in third year and someone said there was an opening at the Film Board in the art department, so I brought some stuff down and uh they liked me and they liked the stuff. I started doing mattes and things. Animated arrows, things like that. You know, until one day I told the guy uh look if I do one more of these things I’m going to vomit, and that was the turning point and somehow I started work more in film and less at a desk.” (Arthur Lipsett Project: A Dot on the Histomap)

How often I like to cling to the notion that I am busy making important decisions about my life. But when I look back at my once and future loves, the movies I made and more importantly never finished, the friends who have drifted into the viewscreen, it is difficult to avoid the feeling that it is nothing but an accumulation of accidents. Yes, I can pick the brand of toothpaste, the colour of jeans, or what kind of brown rice is optimal for dinner tonight, but the big turns, the decisive moments, these all appear as random encounters. Lipsett describes his being hired by the Board as “pure chance;” he is a sculptor student, interested in wood, not movies. And already in this first Lipsett contact narrative, legendary NFB producer/director Colin Low hints at the artist’s famous reclusiveness, his language that was not quite language; could we name this already the beginnings of a private cinema, a private speech? When Colin says that his young visitor was “very articulate… when he was trying to describe his enthusiasm for what he was doing…” we can already hear how very inarticulate Arthur appeared while weighing in on other subjects. Even at the height of his powers of elocution he is only “trying to describe,” in other words, he doesn’t quite arrive, the words don’t finally reach their destination. Hello mumblecore. Welcome home Dada. I’m going to talk to you in a language that only I can understand. And the closer I get to the heat of my truth, the further away I get from any language you have ever heard. I’m spitting words in your face, my face already wet with your exclamations, but we can’t understand a thing we’re saying. As if language was only a pretext for other, deeper failures.

Secret

I only want to talk to you so I can keep my secret. My sentences are going to point at my secret. Like the arrows I’m busy animating each day. The words sound like they’re about… well, what are you interested in, anyways? That’s what they’re going to sound like to you. Call it the Rorschach effect. The content, the what’s-it-all-aboutness of these words, are the foreground, and the foreground isn’t interesting, only the background is interesting. I’m going to work to remove the foreground, to empty it out, until only the background is left. Are you still here? Still with me? Because in the background there are only arrows pointing at an absence.

Talking to you. It’s like watching someone walking backwards in the snow, erasing their traces.

My talking helps me keep my secret. And then my movies. How does the safeguarding of my secret begin when I make a turn towards making movies? It begins as a sound. It shouldn’t be my sounds, it shouldn’t be my recordings. No, the sounds that are going to tell my secret will come from others, from what others don’t want. What did the Buddha say? That his tribe, his congregation, should sew their robes only out of discarded fabrics — menstrual cloths and rags. The dharma would arrive dressed as the forgotten, the left behind, the despised and repressed. Lipsett set out in the same way, his cinema began in the outtake bins of the National Film Board, searching for sounds. These were “trims,” throwaway fragments that properly belonged to other “important, official, sanctioned” movies. His project, and this is crucial — was not official. He worked after hours, when the real editors had gone home, and stole small shards of the documentary harvest that was growing all around him, and brought it back to his midnight Moviola where he could play and replay these chance encounters.

Derek Lamb: “What Arthur did in a really revolutionary way was, he really withdrew in the day-to-day here, although he did continue his day work. At six o’clock every night, when the sound editors had left the documentary area, downstairs, Arthur would go in there and take, filch, steal, all the out trims from the editors, and all night he would just sort through that sound. He’d find little pieces that interested him and he would wind them up into little rolls. In the morning I would come in sometimes and there was Arthur just about ready to go home and sleep. But he had gleaned fifty pieces of little, rolled-up magnetic sound tapes, labeled with rubber bands around them; often in an open 35mm can. As I’d come in in the morning he’d offer them to me and say, ‘Have one, they’re delicious.’”

While you are sleeping I am working. And while you are working, I am sleeping. My schedule, my language, my secret project. My secret needs. I’m going to take your garbage, I’m going to find what you have no use for, the parts of yourself you can’t stand or integrate, and I’m going to make my song out of that. And you won’t be able to resist me then, because I’ve made it out of you, out of the parts of yourself that you can’t recognize as parts of yourself. Call me the garbage man, the trash collector. I’m here to sing in the choir of the unheard voices.

“’He insisted that everything had a sound or a force field,’ explains Judith Sandiford. ‘He had that kind of intensified perception of things. I didn’t know anyone who paid that much attention to the world. It was this intense capacity for observation that later became unbearable for Arthur. He bought industrial ear-protectors because he couldn’t bear hearing things. He was just too sensitive. At first he got them because of noisy neighbors, then he began to wear them all the time. Inanimate objects had symbolic importance for him. His films made you see things you didn’t see otherwise.’” (A Clown Outside the Circus by Lois Siegel, “Cinema Canada,” October 1986)

Is this why Arthur begins his trek into the movies with sound? Because everything in the world “had a sound,” whether it is audible to merely human animals or not? The sounds of the world are a calling perhaps, in this instance from editing rooms left open to prying ears, a mistake he himself would remedy by wrapping chains around his own editing equipment. But that would be years later, after the tumultuous and instantaneous success of his first ever movie.

Bob Verall: “One day he played this soundtrack to Wolf Koenig and myself, and we were not just amused, we were absolutely intrigued by what he’d done. He’d pulled stuff out of films that Wolf had been involved in directing. Anyways, that was the beginning of what turned out to be what many people – and I would include myself in that group — thought was his most famous film, Very Nice, Very Nice.“

Colin Low: “I went to Tom Daly and said, ‘Look, Arthur wants to start this project. He’s already done this work. Why don’t we give him a production number?’ And I don’t remember what the name or the production number was. But it was enough to buy film that he took to, I think mainly England, and when he came back he had a large stack of stills.” (Arthur Lipsett Project: A Dot on the Histomap)

The myth is that Lipsett’s work is a regrouping of other people’s pictures and sounds, that he is a motion picture cannibal, a composer. But having plundered the documentary hopes of already well-known directors like Koenig, and then worked up the nerve to invite Koenig himself to listen to what he had fashioned out of his thievings, Arthur then set off for England. I think it was necessary for my Arthur legend to leave home. In order to begin — or else to fool himself, to imagine he wasn’t beginning anything at all, but just playing, exploring, developing a private language — it was necessary to pry open the secrets of others. The private domains of others. And then in order to produce pictures to accompany these stolen secrets it was necessary to go somewhere else.

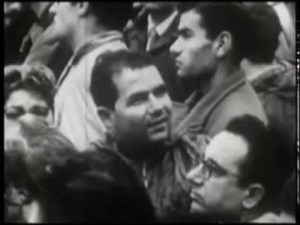

What is striking about the pictures Lipsett uses in Very Nice, Very Nice (1961) is that they are so often faces encountered in close-up, usually reaction shots to unseen events. He leaves home, he travels across the water, so that he can get far enough away from everything he knows, in order to get close to these strangers. One can imagine this brash, ill-spoken, twenty-something jumping through the streets of London with his pawnshop Leica, marching right up to people in a moment of absorption in order to catch their surprise, their terror, their amusements, their stunned shock. At times it’s clear he’s found a perch where the light is perfect and he can survey the surveyors and remain himself unseen. But mostly he is out on the streets, a paparazzi of the everyday. He is far enough away to get close, and what he is looking for out in the open, in the light of these new London days, is exactly the same thing he is looking for at night in the editing bins. He is searching for some private truth, when the mask of the face drops long enough to show itself. He is part of a new generation of street photographers who have given themselves over to the cultivation of chance, “pure chance” as Arthur named it. And he is following his chances like a compass as they lead him towards faces that are opening in spite of themselves. They are faces caught in the act of looking, seeing some moment of the world for the first time. There is something horribly naked and unprepared in all this looking. I’m going to take your picture so I can show you what you look like when you are looking. He is blindsiding his charge, his people, his first audience. He is stepping into their blindspot and exposing them, one frame at a time. Mercilessly. He is stripping them away. He learned early in life how adults can strip every defense from a person, and now he is back leaning into this moment, Leica at the ready, so that as soon as the mask slips, he is there to absorb the secret. The slip, the mistake, the unknown face, the face we can’t bear to show, the garbage of our face, this is what Arthur is busy collecting when he gets far enough away from home to make a picture of home. He is still young enough to imagine that everyone is like him, carrying the terrible burden of a secret, and he is determined to hold onto his by ruthlessly exposing everyone else’s.

Sometimes a picture doesn’t show you what’s there, it shows you what isn’t there. Sometimes a face doesn’t show you what it’s feeling, it presents a fog of distraction, so that the difficult truth stays buried. The more I look into faces the more I can see how they’re always revealing more of us than we would like. Some part of us is hip to this, of course, and is busy working, trying to shut everything down, to smooth out our expressions, to lock us up inside our own prisons of duty. And then there’s another part that is always trying to break out of prison. Maybe that’s what our faces show again and again, the way we escape from ourselves. The way we free ourselves, even for a moment or two, from our own jailors. Until you get old and give up, and then your face can’t show anything except the place you used to escape from.

The faces Arthur collected for his first two movies — the first as still photographs, in the second, 21-87 (1963), as bravura 16mm street portraits — show a population in full recoil from modernity. We had suffered the ravages of war, and in its wake there was a steady stream of consumer offerings. Arthur uses his destroyer-camera to wade into the merchandise consolation and science hopes of a newly infantilized generation. He photographs everyone as newborns with adult faces. Born yesterday. In Very Nice, Very Nice (7 minutes 1962) the faces are blurry and large, downcast and worried, thoughtful, dreamy and angry, and mostly seen cut away from their surroundings. Each face is the only one left in this world. These portraits demonstrate a new form of loneliness; our cities have created a loneliness that can only be experienced when we are together. Arthur takes his scissors to magazines and enters the picture world like wading through a crowd scene in London, cutting up the advert moments so that he can find the sadness and absurdity in these smiling processions. The atomic bomb and rocket launches provide real time science interludes, a reminder perhaps that the new technological saviours are dealers in death, just like the old saviours. There is some tragic and overwhelming sense that we are all in this together, part of some larger ensemble, part of each other even, but that we have arrived unprepared for the dance, still clinging to some older and more primitive form of self-interested absorption.

Bob Verall: “Very Nice, Very Nice took the place by storm. Nobody from the top management on down had seen anything quite like it. Arthur wasn’t that well known in the place except as a new member of the animation department. But it was recognized that he’d pulled something off that was going to make waves, and indeed it did.” (Arthur Lipsett Project: A Dot on the Histomap)

Impossibly, Arthur’s first movie is nominated for an Oscar, and he stands as a young-old man of twenty-five at the dizzying pinnacle of his career. Newspapers call to interview him. There are trips and invitations. His in-house status soars. Whatever you want to do, just name it. All of a sudden the young man who had been committed to keeping a secret, whose movie life began as a secret, and by chance, was surrounded by words, a medium he would never fail to struggle with. And one can only imagine the treacherous new obstacles of envy and respect that crowded around his new office. He had swallowed pills from both jars, and now found himself at once too large and too small.

Colin Low: “I believe he was lionized too early. Arthur couldn’t handle his instant celebrity status. He had fallen into a stupid syndrome where you think you have to make a film that gets even more attention. His work should have matured more slowly. As time went on, he became more frantic.” (A Clown Outside the Circus by Lois Siegel, “Cinema Canada,” October 1986)

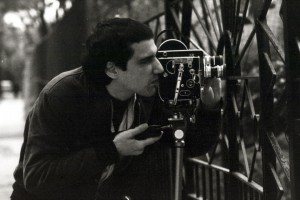

After his Oscar nod, Arthur buys a Bolex camera, the ur-machine of the film avant-garde. It is a Swiss-made, wind-up joy of a camera, a geek’s delight, with interchangeable lenses, and capacities for single-framing and in-camera rewinding. He teaches himself to shoot, taking the camera with him everywhere, and he has beginner’s luck and a frightening, nearly incandescent intensity. Once again he throws himself out into the street to look at faces. He charges towards them, he pushes his camera up into these strangers, he fills the frame with their stunned expressions. The Lipsett archives must contain dozens of outraged reaction shots as his subjects turn towards Arthur. Who are you exactly and why are you sticking that thing in my face? Though these are not the faces that appear in the film, they are part of the cost of finding these faces, of making these secrets public. It takes more than nerve to trespass in this blatant way, it requires urgency, even desperation. Arthur shoots fashion shows, and a circus and people rising up out of the escalator with that same faraway-too-close ethnographic stare. As if he were making a science fiction film. He would never shoot anyone or anything quite as perfectly again. He’s twenty six, twenty seven years old. These fragments would be gathered up in a razor blade of a film he called 21-87 (10 minutes 1964), an enumeration that recalls the hopeful query made by Lipsett champion and producer Colin Low’s “Why don’t we give him a production number?”

Arthur: “21-87 could be described as a fragmented ten minute shock-state which the spectator must grapple with, continuously counter-check and question; at several points in the film a good-hearted friendly voice delivers this line – ‘And somebody comes up to you and says, isn’t your #21-87 – boy does that person really smile.’ 21-87 is an extreme statement of anxiety by a young filmmaker who considers the film as ‘transitional;’ that is – this film can also be viewed as an arrested moment in the work of an artist, caught in the act of departure from surface realities in the search for an expression on film of heightened inner states which could transcend experiences of the known world. This desire for transcendency can be seen in ‘21-87.’” (Arthur Lipsett, “21-87” [1962], Production Files, National Film Board of Canada Archives, Montréal. ©National Film Board of Canada (1962), all rights reserved)

This is how Arthur pitches the movie he wants to make. It’s a young man’s language of course, and it’s so interesting the way he puts it, the way he names his ambitions. When he describes an audience that has to “grapple with, continuously counter-check and question,” surely he is speaking at least in part about himself, and his own process of doubt and inquiry. Instead of presenting the movie as a finished resolve, he says instead that it is “transitional,” an “arrested moment in the work of an artist,” as if the real work never stops, and that the best is still to come, afterwards, in a form that may never be seen or even understood. It’s a curious phrase, this “arrested moment” of a movie, as if Arthur’s being forced to say something before he’s ready to say it. Is that why his language so often appears difficult to others? He has been newly liberated by the success of his first film, given carte blanche on another project, but he finds his new freedom somehow confining. Inside this freedom he can only offer something that is arrested, still born. He is under arrest somehow, locked up inside new identity pressures. His first movie was made as a kind of secret. And he was in the business of stealing other people’s secrets, their garbage, he was part of the underground. He lit out into the street to find the secrets we wore on our faces, when we stopped composing ourselves, when the masks slipped. Arthur is a man whose past was filled with secrets (Why did she kill herself? Why not me? Why am I still here?), and one can only imagine the difficulties he had, as a young man, of founding a practice on secrets inside a building filled with government filmmakers, where desires needed to be voiced out loud, explained and justified. How do you tell the boss: I want to make a movie so I can keep my secrets alive?

Questions

Arthur Lipsett: “The areas I’m most interested in, are for me in question marks. I don’t start out with the answers.” (Arthur Lipsett Project: A Dot on the Histomap) Nearly every conversation I wander into is haunted by the question of the answer. The need to know. The will to certainty. Did I pick up this book in order to understand less? But what if I were a filmmaker who needed to keep a secret, or whose work was deeply connected with the larger secret we call “society?” Perhaps we can take Arthur at his word when he says that the areas he is interested in are question marks. What does it mean to become a question, to set off in pursuit of questions, instead of answers?

If he were still alive I would want to ask Arthur: how do you make close-ups that are so far away from your subjects? How do you manage that close distance? Of course, he’s no longer around to drop us a clue, but his sister Marian might still weigh in. Here’s her description of meeting her second mother, at the ripe age of twelve. Perhaps this is the ground, the family life, the necessary wound that makes Arthur’s early camera encounters so fraught.

Marian: “The last year we were at Camp Macabee, he (father) came up to get us, and as we were driving home he said to me, ‘Would you mind if I got married again?’ It was said just like that, in a sort of calm, ordinary type of voice. He didn’t explain how he met a lady and how they had got very close to each other, blablabla. He just said that. It was sort of like, ‘Would you mind if I stopped for a quart of milk?’ That kind of question. ‘No I guess not.’ What do I know? So it had been arranged that my dad would take Arthur and me — I was twelve, Arthur would be fifteen — to this lady’s house for supper where I would meet my new step mother. That was the first and the only time I met her before they got married. Ten days later they were married. We were not invited to the wedding, and they went off to a little trip to Québec City.”

How tempting it is to read a life backwards, as if it were a story with a drawbridge holding beginning and end in a single gesture, instead of a jumble of patterns, rising and falling away. Perhaps the most important parts of a life are not the through lines, the clear roads, but the hapax legomena, the moments that occurred only once. The singular instances. The never-repeated sentences. The look on the face of his twenty-year-old girl friend when she said yes for the first time. The way you can see colour in black and white. Being arrested by the FBI and dancing for joy. Hand lettering edge codes. Editing black flies out of a Northern Affairs documentary. Talking to the TV, the toaster, the blender and the electric shaver. Seeing the concentration camp number on the forearm of his new mother. Sawing his beautiful chair into little pieces. Staying up all night with his new friends, listening to the refrigerator. Buying the rope.