Listening: an interview with Hildegard Westerkamp by Heather Frise and Mike Hoolboom (October 2020)

Listening: an interview with Hildegard Westerkamp by Heather Frise and Mike Hoolboom (October 2020)

Music Lessons: Osnabrück, Germany 1956

I started taking piano lessons when I was ten. Before that I just ‘doodled’ on the piano, but also played the recorder, which was always my favourite instrument. I think I learnt to play it by imitating my older sister. I never had lessons and so I wasn’t afraid of it. My mother would play the piano and both my sisters and I would play recorders. Later I also learnt to play the flute.

When I was fifteen I met my best piano teacher. I was already a bit ruined, I was used to routine learning, not playing with my heart. By that time I was playing Mozart sonatas but didn’t know how to listen, or to have confidence and trust in my musicianship. The piano is such an interesting machine, it can fool you into thinking that it makes the music for you, no matter what you do with it. The idea that my touch could actually change the sound I made, that had never occurred to me. This teacher, Fräulein Mentrup, taught me much about listening.

She also listened to me as a struggling teenager. I would come to her lessons and sometimes we would just talk. She listened to my difficulties with school and family. She wasn’t a therapist, she was just very present in these conversations. She’d also tell me about her brother with whom she struggled. Most of all she taught me what it’s like when someone really listens to you. That had a lasting effect on me.

Some of this is in Klavierklang (2017), which I wrote for Vancouver pianist Rachel Iwaasa. It’s about the piano lesson situation. “During the past few years Rachel and I often reflected on the challenging and traumatic, but also inspiring experiences we have had with piano teachers, the roles our mothers’ ears played in our musical development and how much the piano has been both a sanctuary for sonic explorations and soundmaking, and a site of trauma and discouragement.” https://www.hildegardwesterkamp.ca/sound/comp/1/Klavierklang/

My mother was an amateur musician who loved the idea of us all playing music. She would often be in the same or the next room when I played and if there was one wrong note I’d hear which note I should have played. (laughs) I know she meant well, but actually it was not good in the long run. This corrective listener was always there even later during my music studies, a kind of internalized judge, always on guard, listening for mistakes. And then of course there was competitive listening in our family. My sister would turn on the radio and there would be a classical piece. Who would be the first to guess what it was, and the composer? Of course as the youngest I could never keep up with anybody. But I learned a huge amount. This was limited to Baroque and Classical music. There was no Romantic music. My mom loved Wagner, but you couldn’t talk about that because of the Hitler time. Contemporary music was out of the question. It was just one huge screechy thing that wasn’t listened to. (laughs) When it appeared in a classical concert everyone laughed and scoffed, that was the attitude.

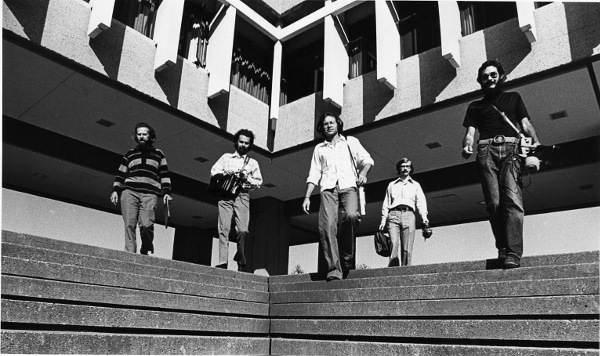

World Soundscape Project 1969-75

I was a music student at the University of British Columbia from 1968-72. R. Murray Schafer came from Simon Fraser University in my third year, I think, to give one of those noon guest lectures. He set it up in an unusual way, with four music stands onstage, each representing a topic. At one stand he talked about noise, at another his travels to Persia, another his music, and finally silence. In the middle of it someone from the audience would get up and ask: how many birds have you heard today? Or: what was the first sound you heard this morning? How many airplanes have you heard today? Those were my future colleagues in the World Soundscape project, their planned interruptions were part of the talk.

When I walked out of that lecture I suddenly noticed all sounds around me. I never forgot that moment. A few years later I phoned Murray and he invited me to come up and talk with him. A few weeks later he hired me to work with the World Soundscape Project (WSP). This was in the summer of 1973. At last I had landed in a place where my listening ear felt truly engaged: I was allowed to listen to the whole world. All of us in the WSP were musicians or composers, but we were also trying to understand what was going on environmentally, socially and politically in terms of noise pollution, what humans are doing sonically to the environment. Murray was writing his seminal book The Tuning of the World (1977) and the whole group was working on The Vancouver Soundscape, which was published later that year in the form of two LPs and a book. In these contexts my colleagues made many environmental recording and we studied everything from the physiology of the human ear, to how sound behaves in the environment, to architectural acoustics, the influence of landscape, wind and weather on sound, to the psychological effects of sound – to name just a few of the many aspects of sound and acoustics that we researched. We also learned about noise measurements, legislation and enforcement, and were connecting with legislators, various levels of government and community groups fighting noise. We were activists determined to make the world better sonically.

Soundwalk

In 1973 Schafer initiated a one-day noise workshop at SFU for all the officials from the Greater Vancouver Regional District, representatives from all the municipalities. They were attempting to improve noise bylaws. Schafer wanted to teach them something about sound and listening. He gave a lecture that was followed by workshops. I was the only woman in the room, my role was doing the soft stuff, a soundwalk, which I’d never done before.

A soundwalk is an opportunity to go for a walk and listen to everything you hear. You can do it in groups, alone, with maps, with or without recording equipment. In this instance I made maps with listening points where I would ask questions like: what sounds drift up from the valley? Stop at this air conditioning outlet and listen to its frequencies. What are the characteristics of this compared to other air conditioning outlets you encounter on campus? The participants of the workshop were sent out with this map and upon their return we discussed their experiences.

That’s different than what we do today. Now in Vancouver we lead people on a route and listen altogether, we don’t speak, and then afterwards, very crucially, we have a discussion about the experience. The whole thing lasts from 1.5 to 2 hours, including the discussion. The walk is usually an hour. Other than learning to listen consciously to the sounds of our environment, a soundwalk can also be perceived as a framework that gives all participants an opportunity to get in touch with their own listening. It’s a time in which we can explore our own relationship to the soundscape, how we listen to it, how we react to sounds and significantly how our listening experience compares to that of the other participants.

The original idea behind soundwalks was: we have to listen to the soundscape precisely because things are not great and we need to change them. This was Schafer’s argument: if we keep on blocking out noise, we won’t notice how much it is spreading. That’s why we have to listen to the entire soundscape, including noisy ones. Let’s go downtown and listen to what’s happening sonically, analyze it and try to understand what’s happening to our bodies, our ears. Why are the sounds sounding as they are in that particular environment? Would they sound like that in other environments?

At that time the emphasis was on listening to environmental sounds in the face of ‘the noise problem’. Over the years for me and for others, there has been a shift. Getting in touch with our own listening has become more conscious. As we’ve become more knowledgeable about ecology being about the relationship between environment and person, soundwalks are an opportunity to examine that relationship. You get to know what kind of listener you actually are. You uncover your own reactions, attitudes, and responses, and that in turn has an influence on how we deal with the environment. To me, that’s the essence of ecology, to understand that relationship and to examine our part in it. Who are we as sound makers? What kinds of sounds do we make during the day? How do we contribute as a sound maker to the quality of our environment?

At the beginning soundwalks were connected-for me anyways-to a kind of community activism, intent on making positive changes in problematical soundscapes. Today soundwalk participants speak more willingly about their own personal experience, their discovery of listening and the way this affects them. But what is often lacking in these discussions, is a more analytical approach, addressing the concrete facts of what was actually heard, the acoustic behaviour of sounds in certain environments, their physical and emotional effects, associations that may have come up for participants, and what all this may mean in the larger context of acoustic ecology and its potential role in social, cultural and political issues in a community. In other words, should we not let the sound experience touch our own emotional intelligence beyond the Self and allow for a more activist mindset to enter, addressing larger concerns for a community’s sonic well-being? In the 1970s activist rhetoric tended to dominate noise issues and it wasn’t part of the social make up to talk about our own inner listening experiences so much. Today it is the other way around. In my opinion we need both if we want to understand the acoustic ecological issues we face in the world: concrete knowledge of what goes on acoustically in our soundscapes and a deep understanding of our own listening and our responses to what we hear, as individuals, communities and larger cultures.

Listening to your own thoughts is part of the process in a soundwalk. You’re not only listening to the environment but also your own thoughts. Can you catch the moment when your listening switches from your thoughts to the environment and vice versa? Some people become strangely obedient to what they think is the focus of a soundwalk: that they must listen to the environment at every moment. But that’s not the point at all. In fact, we cannot listen to the environment all the time. It is natural to our aural perception that we switch focus and listening levels continuously and that includes listen inward, to our own responses, our own thoughts. In fact, we may be so preoccupied with our thoughts that we hear nothing of the environment. The key is to become conscious of this fluidity in our listening focus.

Why are we not listening to the environment at certain times? What happened? Is it a dominant thought in yourself, or was it the environment that discouraged you from listening?

Noticing and understanding these shifting dynamics of attention between “place and us” inevitably confronts us not only with ecological questions, but also social and political ones. Who are we in this world and to which voices do we pay attention? Why have we let noise proliferate? Why have Indigenous people or people of colour not been heard? Or women? Or persons in the LGBTQ communities? Why did we need a pandemic to finally notice the sounds of nature in new and significant ways? We can learn much about this through soundwalks. They can sensitize us, even become a daily practice, a bit like meditation.

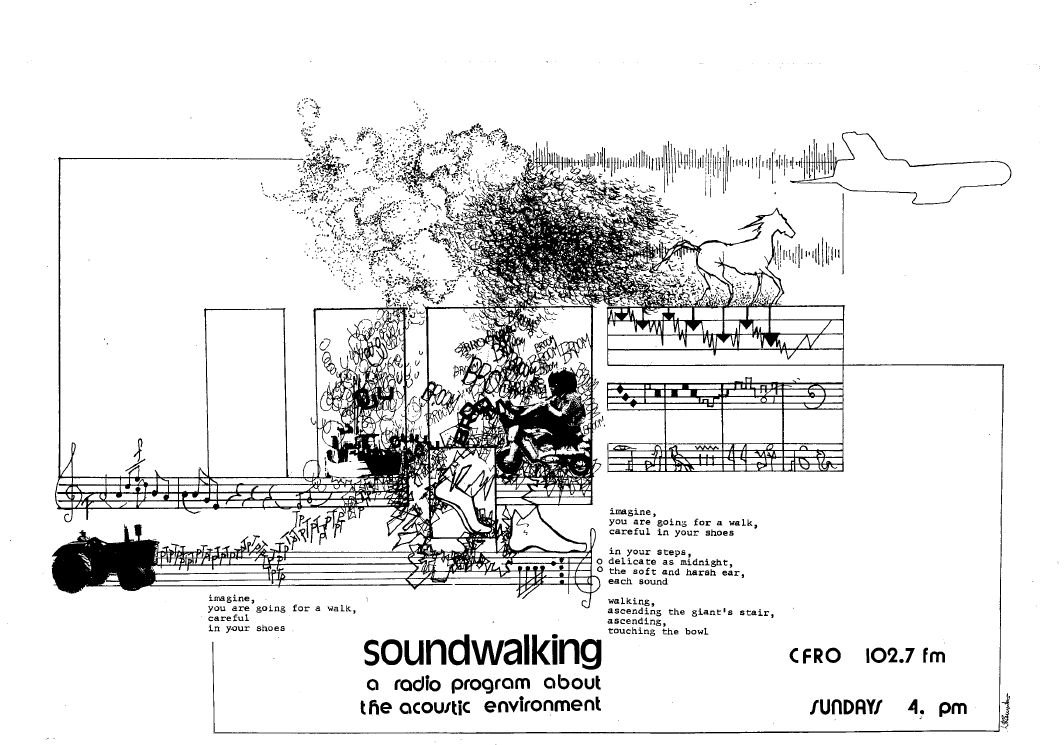

Co-op Radio 1978/9

Vancouver in the 1970s was being reinvented. Vancouver Co-operative Radio started at that time, the Western Front, Video Inn, all these cultural and political awakenings.

I had the idea to transfer the concept of soundwalks into radio. I got a Canada Council grant for a Co-op Radio program called Soundwalking. For a year I went out to record anything I felt like for this weekly program. Most people who were doing environmental recordings were birders, or natural sound recordists interested in water, animals, winds. But to record a city or community life had only been done by very few (e.g. Tony Schwartz in New York, already in 1955, the WSP). The recording technology had only become portable fairly recently. I had one of the first portable cassette recorders, a Nakamichi, that took eight D batteries. It was big and heavy! I had AKG microphones that were pretty good quality.

I would make recordings each week. A walk up Hollyburn Mountain in the snow. Visiting a brewery and talking with workers. Standing in the fog on the sea wall. Visiting a bird sanctuary. Walking through a mall. And much more. The main thing was my passion for listening to the environment and I wanted to share that with the radio audience: let’s listen to Vancouver and find out what sounds appeal and what you find hard to listen to. It wasn’t overtly educational, that was just my motivation. Even though my show was on an alternative radio station it still stuck out. It changed even this station’s radio rhythm. I’d come in after the folk music show and make a cross-fade into my show and everything slowed down. It doesn’t matter what you listen to, whether it’s the traffic outside the window or the beach, it doesn’t have musical rhythm. The responses I got from the shows immediately before and after was puzzlement. What the hell is she doing? (laughs)

Initially I would play a whole hour without interruption, but eventually I introduced my recordings a bit more to focus people’s listening a bit more. I knew that people block out environmental sounds naturally, and if you put it on the radio they’ll also block that out after a while. I wanted them to listen, so I started giving the context, the date, the weather, where I was, I would point things out. My voice was a mediator between environmental sounds and the listener. I was like a slow motion sports announcer on the radio, informing the audience about what they couldn’t know about just by listening

I was very conspicuous while recording, wearing big headphones. Often people would approach me, mostly men and children, to ask what I was doing. We would start talking. I was not a journalist in the traditional sense, sticking a microphone into someone’s face. These people would come to me because they were curious. I was a stranger in their environment, the microphone was a listening agent. These were very interesting voices, words and expressions, sounding mostly relaxed and quite natural. It was unusual to hear voices like that in the conventional media environment at the time.

Whisper Study 1975/79

Environmental field recordings don’t behave like musical instruments. You can only get so-called clean sounds if you go into the studio and record the sounds you want to use. Then you have your sound objects, your instruments. If you go into the environment you’re dealing with life, and life upends you. (laughs) And you cry. Or laugh.

The first time I experienced this was with my first piece Whisper Study. I had a studio recording of myself whispering “When there’s no sound, hearing is most alert,” words by Kirpal Singh. Schafer had quoted them a lot and I was fascinated by that sentence. I recorded it, and then Barry Truax showed me a few studio techniques. I didn’t realize I was doing a piece, I was just “exercising.” I had learned delay-feedback and looping and made a sound overlay of my whispering, using multiple whispering sounds. Then I slowed that down multiple times on our analog reel-to-reel tape recorders, mixed the different speeds together and suddenly heard this unbelievable sound, a slurping, clicking river emerged from this density of whispered sounds. I was stunned by what I had found! I had known nothing about sound processing prior to this and was so excited by this sonic discovery that I had to leave the studio. I went for a walk and wondered: what just happened there? Sometimes when you sit by a creek you hear all sorts of subtle little things, even voices, you imagine things, your acoustic imagination flourishes. I felt I had created a soundscape like that. This experience of discovery, of absolute surprise, hooked me to the studio.

The original piece was in three parts. The first part is a little bit of that whispering, very very quiet. The middle part is the liquid river. Originally it ended with a low frequency wind sound, one of the whisper sounds slowed down. A few years later, my then-husband Norbert Ruebsaat wrote a poem after hearing this piece entitled When There’s No Sound Hearing Is Most Alert. I took that poem up the mountain when I was recording for the Soundwalking show in the snow. I read it up there, with snow footsteps and playing on icicles and included it in the end section of the piece, the underlying wind sound still there.

Beneath the Forest Floor 1992

I received a commission from the CBC to make a new work. The Toronto studio had its first all-digital facility and I was asked me to bring all my raw and unprocessed recordings and work with them from scratch in that studio. This was scary because I was not used to working with a technician. I’ve always worked alone in studios. But the knowledge that I would work in an all-digital facility motivated me to make recordings in a wilderness environment, the Carmanah Valley on Vancouver Island, one of the quietest places on the west coast. I rented a high quality microphone, a Sony SM5, that was clear with a wide range.

I’ve always been interested in silence though the piece is not quiet. My mother said: “That’s a pretty noisy forest.” (laughs) It’s more about the state of mind, the inner quietening, that occurs when one spends long enough time there, very different than quiet in the desert. The old-growth rainforest is like a cathedral as people often say, it has a grand and spacious silence. Any sound that occurs, like a raven call, is full of forest reverb. But at the same time it’s also a very mossy place, the ground is soft, wet and dripping.

As soon as you enter this forest, something happens, something in you calms down.

In German there’s a beautiful word for a primal forest like that: Urwald. Something ancient, almost mystical. I grew up in Germany near a forest of beech trees, which was not ancient. The trees had been planted in rows, regularly spaced, but with time, nature did its part to add variety and irregularity. As a child I thought that’s what forests looked like everywhere. In contrast, being in that section of the Carmanah forest, that had not been logged and had been put under protection, one experienced on a visceral level a pristine primeval environment with its ecosystem clearly intact. The songbirds gathered in parts that had more light and undergrowth, other sections were darker and mossy and the soundscape changed accordingly. There were different microsystems with everchanging contours, plants and animal life as you walked along the Carmanah River. It wasn’t just one mono-culture with the same kind of trees in rows.

This experience was powerful enough for this European settler person, that in the first part of the composition I wanted to introduce the environment in some detail, taking the listener to the place of the squirrel, the river, the creaking trees and the storm, the place of the songbirds and so on. A regular drumbeat-like sound provides a kind of sonic punctuation that takes us into each of these places.

The recording process is about walking into the forest and recording until your battery runs out. (laughs) There are always surprises, it’s a bit like when you’re planning a soundwalk. We had just finished recording and had walked into the parking lot when I heard a raven approaching. I quickly turned on my recorder again and stood there until the raven flew straight over the microphone. Its sharp raspy cry made in close-up has a gorgeous reverberance that ironically, comes from the unpaved parking lot surrounded by trees. This raven’s call, slowed down five octaves, gave me that throbbing sound in the piece. That was another one of those magical moments in the studio. It reminded me of a First Nations drum. No other raven sound recording gave me such a sound when slowed down in a similar fashion. This one contained the inner sonic reference of the original Indigenous culture in that forest environment. The raven, like a trickster, became a musical instrument that determined the structure of the piece, certainly the opening four minutes. It guided us from place to place.

Then my mind went further. The drumming sound made me think of trees and totem poles. Was it possible to make an aural totem representation of a place? That was a larger task. What did I really want to say about this place? It gave me more of a mythological underpinning and I connected it to the 19th century Romantic writing about the German indigenous forests that flourished at the point when they started to disappear. There was an interesting intercultural connection around forest mythology. I felt underground connections, the roots, a dark side. What is the forest in us? That depth helped me to keep on working, and eventually I came up with the title: Beneath the Forest Floor. I had nearly finished when the title pulled it altogether.

I’m not someone who is good at working with a pre-determined structure and then filling it. In the classical music tradition you have a sonata form. You put the music into specific themes and do that as creatively as possible and then you have a sonata. I can’t do that. With environmental sound you never quite know what you get. What happens in the processing of the sounds, and what kind of instruments emerge from studio processing, becomes a new orchestra. Then you have a conversation with your own experience while recording, and what the environmental sounds bring to you. How can I let them speak about the place in the best way? The structure comes from there. It’s a very different approach from traditional composition. It means that your own intent may be completely upended, you’re adjusting to the surprises of your own recordings and studio processes. It’s about relationship. What does the environment say and what do you want to say? Composer and environment are in a constant conversation. By the end of the piece you’ve helped each other.