Loop, Print, Fade + Flicker: David Rimmer’s Moving Images by Mike Hoolboom & Alex MacKenzie

The Pacific Cinémathèque Monograph Series was initiated to explore the spectrum of contributions and innovations of Western Canadian filmmakers, videomakers, and fringe media artists. Monograph Number One focuses, fittingly, on David Rimmer, one of Canada’s foremost experimental filmmakers. The book is available for purchase here: http://www.anvilpress.com/Books/loop-print-fade-flicker-david-rimmer-s-moving-images

“There is no better way to start off Pacific Cinémathèque’s Monograph Series, celebrating West Coast filmmakers, than with the work of David Rimmer. Mike Hoolboom’s essay tantalizes us with a romantic myth that contextualizes David, while Alex MacKenzie’s interview lets the artist speak for himself. Both offer a unique insight into the art practice of one of the most influential Canadian filmmakers of the 20th century.” Ann Marie Fleming, independent filmmaker and visual artist

“For David Rimmer, film is a way of seeing, a way of experiencing life. And there are no two better filmmakers to take us on this journey of coming to understand Rimmer and his practice than Mike Hoolboom and Alex MacKenzie. Before there was even the awareness of a filmmaking culture in Canada, one “more concerned with dramatics,” Rimmer was breaking the rules as they were being made. Working with film as a canvas, Rimmer’s works are technical experimentations incorporating found footage, optical and contact printing and hybrid film and video forms. Like that other Economics major turned self-taught filmmaker, Guy Maddin, Rimmer is a seminal Canadian filmmaker and a must-study for any student of Canadian cinema.” Cecilia Araneda, Executive Director, Winnipeg Film Group

[Rimmer’s] Surfacing on the Thames is a brilliant film which, in its way, belongs in the same class as Snow’s Wavelength. I’ve never seen anything like it … the ultimate metaphysical movie. — Gene Youngblood, ArtsCanada magazine

The most exciting non-narrative film I’ve ever seen … images become polarized into grainy outlines, like drawings in white or colored chalk which gradually disintegrate and disappear. The film [Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper] resembles a painting floating through time, its subject disappearing and re-emerging in various degrees of abstraction. — Kristina Nordstrom, The Village Voice

ISBN 1895636981

5 x 7 | 108 pages

$15 CAN / $15 US

Rights available: World

Experimental Filmmaker by Thomas Homer-Dixon

(Toro Magazine, June 16, 2009)

Vancouver experimental filmmaker, David Rimmer is one of Canada’s best-known and most internationally acclaimed film artists. His films, uniquely subtle and meditative, explore both the quality of human perception and the nature of film as an aesthetic and communicative medium, often metaphorically.

Rimmer, who emerged as a young visionary in the late ’60s with Square Inch Field (1968) and Migration (1969), two films the film critic Tony Reif described as celebrating “the interconnectedness of all things,” has assembled a remarkable body of films that force the spectator to share in the exploratory experience. Anvil Press has just released Loop, Print, Fade + Flicker, the first in the Pacific Cinémathèque’s Monograph Series (initiated to explore the contributions of Western Canadian filmmakers, video makers, and fringe media artists), which focuses on the work of David Rimmer. Mike Hoolboom’s essay provides context, while Alex MacKenzie’s interview offers a revealing look at one of Canada’s most influential, poetic and visionary filmmakers.

For Rimmer, film is a way of seeing, and right from the outset he was seeing the film medium and its subjects with radically “new” eyes. His films of the early ’70s – Surfacing on the Thames (1970), Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper (1970), The Dance (1970) and Seashore (1971) — incorporated anonymous stock footage and took structural film in new directions. His films Canadian Pacific (1974) and Canadian Pacific II (1975), announced him as one of the world’s foremost cinematic artists. His film Bricolage (1984), established him as a master of the collage aesthetic. Rimmer also experimented with video in the ’80s and his most compelling work of this period – As Seen on TV (1986) and Divine Mannequin (1989) — represented a radical hybridization of video and film.

Rimmer’s more recent films — Black Cat White Cat It’s a Good Cat if it Catches the Mouse (1989) and Local Knowledge (1992) — offer a striking mix of documentary and diary, as well as further exploration of themes and ideas that are evident in his earlier work. If you’ve never seen one of Rimmer’s films you’re missing a truly eye-opening and mind-expanding experience. Viewing one of his films may forever change the way you experience film – and reality. And while it’s difficult to cite any one of them as central or emblematic of his work as a whole, you’ll really get a feel for it with something like Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper, which has been described as “a painting floating through time,” with its disappearing and reappearing subject.

Anvil Press, film/video artist Mike Hoolboom and media artist Alex MacKenzie must be commended for producing this attractive and compact book, which gives one of the bright lights and true innovators in Canadian art much needed exposure. Before there was even the awareness of a filmmaking culture in Canada Rimmer was shattering the rules as they were being made.

David Rimmer by Peter Morris

(The Canadian Film Encyclopedia)

The Vancouver experimental filmmaker David Rimmer is, next to Michael Snow, Canada’s best-known and most internationally acclaimed film artist. His frequently contemplative films investigate both the nature of the film medium and the quality of perception, and go beyond the structuralist/materialist approach to film: they explore the structure of the medium, yet simultaneously operate on a metaphoric or poetic level.

Rimmer emerged as a young visionary in the late sixties with Square Inch Field (1968) and Migration (1969), two films that, in the words of film critic Tony Reif, celebrate “the interconnectedness of all things.” His films of the early seventies — Surfacing on the Thames (1970), Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper (1970), The Dance (1970) and Seashore (1971) — drew acclaim for incorporating anonymous stock footage and thus taking structural film in new directions.

Rimmer moved temporarily to New York and, between 1971 and 1974, worked with a variety of media including video, dance, performance, installation and film. His films of this period were concerned with the unfolding of time, a theme best exemplified by Real Italian Pizza (1971), which condenses six months of New York street life into 12 minutes. He returned to Vancouver in 1974 and made Canadian Pacific (1974) and Canadian Pacific II (1975), which helped establish him as one of the world’s foremost cinematic artists.

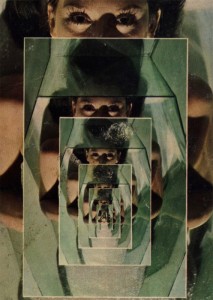

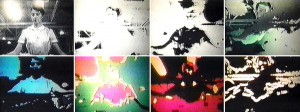

In the early eighties, Rimmer took a four-year hiatus from filmmaking to teach film and video at Simon Fraser University. He marked his return with Bricolage (1984), which established him as a master of the collage aesthetic; it also personifies Rimmer’s characteristic technique of slowing down the viewer’s perception of images and events. Rimmer also began to experiment more with video in the eighties and his most compelling and intricate work of this period — As Seen on TV (1986) and Divine Mannequin (1989) — represents the hybridization of video and film.

Rimmer’s more recent films — most notably Black Cat White Cat It’s a Good Cat if it Catches the Mouse (1989) and Local Knowledge (1992) — have merged his philosophical and aesthetic preoccupations in a striking, stylistic mix of documentary and diary, infused with the insistent interrogations of image and epistemology that are evident in his earlier work.

Rimmer has assembled a remarkable body of meditative, subtle films that expose and investigate the material properties of the very images of which they are constituted. Blaine Allan, in an essay published in the Canadian Journal of Film Studies, has encapsulated Rimmer’s accomplishments by stating he “is not simply exploring how we see nor solely what we see, but the space between the two and the interaction and processes of what we see and how we see it. The spectator is called upon to share in the experiences of exploration and, while a filmmaker such as Brakhage demonstrates the way he himself sees, Rimmer shows us the multiplicity of ways of seeing in general.”

Each of Rimmer’s films is a unique experience. While it is difficult to cite any one of them as central to his work, Surfacing on the Thames belongs in the same class as Snow’s Wavelength (1967).

David! by Mike Hoolboom (2007)

Tune In, Turn On

When I asked Richard if he felt he was part of the ‘avant-garde’ he took a step back and exclaimed, “Avant-garde! That’s like the original six teams in hockey. It ended when I was a kid.” Oh yes, the fabled avant-garde, home at last in the twentieth century, and raised to feverish heights in the sixties with its dreams of feminism and black power and free love and hand-cranked Bolex cameras to make a picture of it all. We would make our own media, tune in, turn on and drop out. And once we were out, far out, our third eyes would show us the visions of the avant-garde and they would look like home movies. Like home.

Where is our revolution now?

There is a small gaggle of folks still carrying the dream. After all this time bent behind cameras they can shoot a movie without using one at all; they just swivel their heads and watch it come down twenty four times a second. Thirty if they’ve switched over to video.

They’ve managed to live outside a collective looking for how many years now? Their look is already a refusal. It is not television for instance, it is not us, all at the same time, saying yes. It’s me and it’s you, her and him. This is what they believe, these grey hairs, these stooped, balding remnants of revolutions past: that everyone needs to look for themselves. There is no uniform law, no ten commandments or reliable science. If it’s repeatable, forget about it, throw it away and start over until you can’t turn the same number over and over.

Who are they? The ones who don’t fit in mostly, geeks and misfits and it’s hard to keep that up past forty. When you’re twenty it’s charming, at thirty it’s eccentric, at forty a societal danger, by fifty it’s no use, they’ll never learn. When you’re twenty and soaked in enough beer to preserve flesh into the next century and you get up for a naked jog around the bar it’s charming, it’s funny, ha ha, pour the lad another and send him home. Try the same number when you’re sixty and the cops are bundling you into the back of the car, no questions asked. Any child past the age of forty should have the decency to stay out of sight, even in the hardly there scrums of fringe media. Just ask Jack Smith.

Artists rarely have a chance to get old in this country. They give up, or head south, or turn their work into a parlour trick for the agencies if they’re really lucky. Mostly other things get in the way. Like family. Trying to make the rent. Security, dying parents, AIDS, the abortion, it means exactly the same thing in the end: no time to make art. That’s a luxury, an extra. If youth is wasted on the young, then art is not far behind.

Long Distance

It’s late Friday afternoon in Gastown and I’m standing with my friend Alex outside a micro cinema he’s called The Blinding Light!! He explains to me that the window we’re settled against was busted up just a couple of weeks back so that someone could grab a handful of CDs that were sitting on the counter. He tells me this with a voice that leans hard into a couple of words, letting me know that if these strangers were music lovers he’d understand, Alex can understand almost anything done in the name of love. But knock down a big beautiful window like that so you can pocket a few CDs and make ten bucks for the next hit? This is capitalism at its most disappointing.

Who walks round the corner right then but David Rimmer. “Mike!” “David!” When I talk to him he looks at me with eyes that never should have been allowed to get quite that blue, and he looks from a long way away. He’s standing up in front of me and we’re so close I can feel the breath leaving him in even measures, as if someone were inside counting. “Mike!” “David!” I don’t know David so well but he likes to talk like that sometimes, in brief exclamation points. And then he goes far away again. He’s long distance, he’s way out there. Standing here in front of me. Where has he gone? He is trying to pull me into focus from that faraway place and it’s hard. I can tell the dream he’s leaving has to be pretty sweet because of the effort it requires to get him back here, right here, and then he takes all the time that is in his face and covers me with it and we stand in this luxury of time like two kings. Where did all this time come from? At last there is time to speak and to say the right thing and the wrong one and take one detour, and then another because that’s where all the juice is. David knows that so well, the juice is in the detours not the straight lines. If you want it bad enough you stay off the roads. There’s nothing on the roads but other drivers. That’s US looking again, that’s the way WE think, and David’s already left US and WE behind. That’s what makes him an artist, his knack for wandering, taking the unlikely detour. He explores chance systematically.

Making Movies

When David started making movies he would take small bits of other people’s movies, leftovers, really no more than a meter or two of film and he would look at them for a long time. When he was young he already had the knack of looking at small things for a long time.

He wouldn’t make a big production out of gathering, he wasn’t a hoarder or collector, he didn’t need to have everything, there was no set he was trying to complete. He took what was coming to him, and if it wasn’t all that much, no worries, that was fine too.

He was a recycler, working with remnants until the audience could feel it right along with him, holding that bit of plastic in his hands. He might dissolve one frame into the next frame into the next, so you’d slowly watch a barge cross the River Thames, along with a storm of golden dust and scratches (Surfacing on the Thames (9 minutes silent 1970). Or he might make a loop and lay some math on it, showing us a frame for how many seconds, and then the next frame for a bit less and so on, as if each frame were an event, an occasion. Happy birthday frame! (Watching for the Queen 11 minutes black and white silent 1973) Or he might make a loop out of a woman throwing some cellophane on a table and then unravel every possible variation, in every colour and combination of colours. (Variations on a Cellophane Wrapper 8 minutes 1970) The way he could measure time and rhyme it out second after second was like a musician working off a riff, like old Bach sitting down at the clavier running out his variations. David could make the fragments sing.

Hands

David has these large hands and who knows if it’s true but this is the fantasy: he has dad’s hands. If anything goes wrong, if the roof leaks or the TV is broken or the washing machine won’t start, no problem: these hands are going to fix everything. Thanks dad. These hands are also a way of knowing through touch, understanding directly, up close and personal. We don’t need to talk about it, never mind about the manual, the way it’s supposed to be done (that’s more of the WE version), these hands will find a way. For the last four decades these hands have attached themselves to an art of machines. The interlocking gears, the belts and drives, the old world of industrial hopes and class struggle and the birth of the unconscious, all that is worked on up inside these machines of cinema, and David’s hands pass through all that, feeling right at home.

Home Movies

Like every dad he likes to make home movies. How much of the Canadian fringe is home movies? There are the diary boys of the escarpment school, the video narcissists, the coming out movies (coming out gay or nerd or Japanese), the trips back ‘home’ to some far flung part of the (not-quite post-colonial) world. But pictures of home have invaded even the work of hard core conceptual artists like Mike Snow: what else is Wavelength but a long look at home? This is a home that used to belong to David too. As a young artist he did the right thing and rushed down to New York, lived in a big beautiful loft in the village, and when it was time to leave he gave it to Mike Snow. A year later it was on the cover of Artforum.

Home spun. Home truths. Home made. The Canadian fringe is home made.

New York

While David was in New York he set his camera up by one of his windows, looking at the pizza joint across the street. Real Italian Pizza the sign read. All kinds of things are happening across New York City but David makes his stand right there, at home. He sets his camera up and that’s where he stayed, week after week, month after month, always shooting through the same frame. And in the middle of that frame: Real Italian Pizza. (Real Italian Pizza 13 minutes 1971) What a beautiful film it is, thirteen minutes of summer and fall, with the folks gathered or passing by, the police and fire trucks, the hipsters and not so hip, they’re all there. When he gets back to Vancouver he takes an apartment in old Gastown and sets his camera up again. This time he’s looking out over railyard and harbour, with the ocean freighters come to dock and the mountains behind all that. Big weather. (Canadian Pacific 9 minutes silent 1974, Canadian Pacific II 9 minutes silent 1975) David’s running all over the city getting into scenes and falling in love and talking whenever he has to but his camera stays at home, looking out over the docks, shooting when the light is right, or when the fog rolls in, or whenever something catches his eye. He exposes a few frames and then he leaves it alone and goes about his living. This living is also a way of seeing.

Al Neil

It must have been on one of those all night, steady-on-up-to-the-bar occasions when he met Al Neil. A veteran prankster, Al belonged to another generation, more beat than hippie, playing an off kilter bebop piano in a style no one had a name for. Maybe they recognized in each other the same kind of being alone and out of this recognition and friendship came David’s movie Al Neil: A Portrait ( 40 minutes 1979). This one really shook me when I saw it, because I’d seen David do his magic act with remaindered footage, spinning it out into something beautiful and precise. But this was documentary territory, this was the Real, the Other, and all those geek chops, all those knowing dad hands, weren’t supposed to be able to prep you for encounters like this. Usually the fringe folks would obliterate their subjects with technique, just bury them in flash and flicker, but not David.

In this portrait of his friend he leaves out most of the stuff you’re supposed to put in a doc, all the experts and important people telling you how ahead of it all Al’s always been. Or people telling you what you’re listening to and what you’re looking at, parsing the moment. Instead, David films Al close-up playing the lonely piano for a long time. David watches his comrade play, and gives us time to hear him. It keeps on coming at you and it’s not the backdrop for the credits it’s the thing itself. He shoots nearly the whole movie inside Al’s strange ramble of a house. We see the totems he’s carved and for a few moments Al talks his talk in that raspy unforgettable voice, coming through the years and the good bottle David’s brought along to make it smooth. Al’s laugh: like a coffin heading the wrong way. And then right at the end of the movie we see him at a packed gathering in a gallery called the Western Front, and it’s a shock. All of a sudden Al’s up onstage at the head of a buzz and he’s got a little serial music in his mouth, he’s going to start off with some Steve Reich ideas he exclaims, and sure enough he does. But inside a few bars he’s back to playing that strange, tortured bebop we’ve been hearing for the last half hour, and even though it’s running out over the crowd we’re inside the music, we’re close to these familiar notes, we’ve found a new home here.

As an artist who makes pictures David has one great advantage which is that he hardly knows how to talk. Never trusted words. All that wind out of the mouth. He can’t fill in the place his pictures should live by talking himself out of it or talking until the feeling stops entirely. He wouldn’t know where to begin. He keeps his mouth shut and his camera open.

Film and Video

David was never part of fringe media’s cold war: film versus video. He did a few turns with video back in New York for instance, shooting some of the right now with the weight lifting machines that passed for video recorders in those days. So maybe it was no big surprise that he hit the 1980s with a video recorder in one hand and a Bolex in the other. But slowly those tight little film circles he was running as a young man got worked up alongside other kinds of loops, and while these moments never collected into anything like storyland, some idea of purity had been left behind so he could chase down other dreams. David was still looking hard at small bits of thrown away media, but instead of running them through their paces and showing what pictures looked like when they were left to play, he wanted to rub them up together until he had something like montage. And in order to pull these pictures out of the trash pile once and for all he had to get them to look different, to look the way he was seeing them all along, and in order to do that he needed video.

What he was trying to do with his film/video hybrids like Bricolage (11 minutes 1984) and As Seen on TV (15 minutes 1986) was keep himself up on the wire. The truth is, he’d found his way early and got right down and painted his masterpieces in the ten shorts he pulled out his hat between 1970-74. Then he trumped his own trick four years later with Al Neil: A Portrait. Most artists would have the dignity to quit, to pack up and change careers, but David went on, though it took him a few years to find a new groove. He was still committed to the short form; paintings weren’t any better if they took up the whole ceiling. So he lays a snippet of epileptic seizure between day-glo-coloured TV bits until the seizure becomes a comment on televisual spasm which he names As Seen on TV. He runs a loop of sound and picture out of joint until the sound comes all the way back and accompanies the picture again in Bricolage. Sometimes it can take that long, require that many attempts, until you see a picture at all. In Narrows Inlet (10 minutes 1980) he takes his camera out on a boat and click clicks a frame at a time even though he can’t glimpse a thing. He’s caught in the fog and there’s nothing there at all until a sliver of colour appears, and then slowly, oh so very slowly, the fog lifts and the tree line lives again, staring back at the camera with all of its colour and height resolved. Another small miracle of looking.

By the end of the 1980s he’s in China, replaying the last twenty years of his life in the movies, only with Chinese crowds pulling themselves into his lens. Black Cat White Cat It’s a Good Cat If It Catches the Mouse (35 minutes 1989) asks: How do I look? He takes it all in with steady precision, up early each morning to catch the only light worth gazing into, except for the last moments of the day, so he climbs back to catch some of that too, finding his way between sleepers and trains and tai chi circuits. He meets his subject half way, not you over there like a zoo specimen, but both of us inside the cage, checking each other out, making contact. David has a knack for finding the necessary distance. Without that distance, it’s impossible to begin looking. Every day tourists are busy turning cameras on but it’s no use, they manage to record everything without seeing a thing. Most artists, never mind tourists, are still trying to find the distance. David is busy showing us how.

His second great ‘period’ comes to an end with Local Knowledge (33 minutes 1992). It is a reckoning and last stand. Not a movie that could ever be made by a young man, its time-compressed skies and hunters and fishers and motorboat reveries narrate a home movie reading of the west coast. Beautiful pictures, one after another, but more than that. He wants to let go because letting go feels like freedom, only it’s not. David’s been around long enough to know that too. Freedom arrives in the net, the frame. Only when the taboo and prohibition have been drawn is the artist free to play. That’s the sad, long lesson of Local Knowledge. Hard because you can’t smile with the same sort of innocence after that.

David has made many movies since Local Knowledge, though none with its urgency or scale. It’s hard to stay up on the wire as long as he has. No one’s managed it longer in this country. He’s still looking for a way back, trying to feel his way through paint splatters on frozen emulsion, or another good look at the landscape around him, or another fascinated discard of footage. He’s been there and back and knows the only place where he’s worth a damn is moving moments together that don’t belong, looking into faces for a long time until he can see clear through them to the other side. He’s the youngest older person I know. Finally retired from teaching, he can give that old dog a rest and with all that new time settling in him who knows what next?