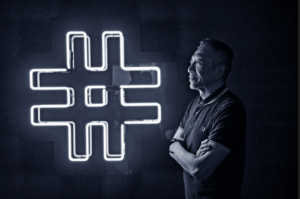

King of the Main: an interview with Paul Wong

2008, released 2021

I meet him at the Metropolitan Hotel, where the Reel Asian fest is hosting him for the week as the spotlight artist. He’s just finished nearly thirty new videotapes, often working with fragments from years ago. When a fire alarm goes off and interrupts out taping, his eyebrows lift and he says to me, “Shall we saunter for our lives?” We made our way down 21 flights, pausing at a peculiar door near the mezzanine which has no handles where Paul stops and composes a digital photo. He is always in the midst, taking pictures,

Mike: Were you born with a video camera in place of a silver spoon? It seems that you have always been standing behind the camera, or acting up in front of one.

Paul: Everyone’s a video artist today, but when I picked up a camera it was rare. In 1972, by the time I got to grade 11, there had already been a lot of progressive movements in education,. Free schools had opened, there were hippie hangovers and counter-culture alternatives. Screw science, let the kids dip candles. That summer I worked on an Art Gallery of Vancouver extension program called The Stadium Gallery that took over an old baseball stadium near my house. It was a community project that occupied unused spaces for a year or two, bringing art into the city. I hired ten youths and we made videos that summer. We took workshops with the man who would become my guru, Michael Goldberg, who was an interdisciplinary artist from the artist’s collective Intermedia. Intermedia was the beginning of Vancouver’s artist-run centre culture. They had a four storey warehouse on Beatty Street and hosted extraordinary happenings and activist experiments and new music and screenings. I had been to some of their events and was deep enough into the scene to be employed by the time I was sixteen to show other kids how to dip candles, and to make a video of it at the same time. We were making things on 1/2” black and white videotape. From the moment I picked up the camera I never put it down.

Michael Goldberg, Patricia Hardman and Noelle Pelletier organized a conference called The Matrix at the beginning of 1973. This became the founding event for Video In which happened a number of months later. It began with a call-to-arms for video folk to come to Vancouver, and they arrived, two hundred of them, a hundred from out of the country. The Vasulkas traveled with their video synthesizer and there were multi-monitor installations and screenings. The registration fee was a videotape deposit that anyone could access upon request, and that we were free to duplicate. 65 titles were retained and I was the librarian. Those titles and the question of their circulation was the beginning of Video In. The hope was to continue developing this network of people and create a library and viewing room. Video In started as a bunch of viewing stations with headphones. It wasn’t designed as a production centre, but there was some equipment of course, including a camera, which was important because there weren’t many cameras in the city. It became our hangout.

The Western Front started at the same time. I helped develop their video program and documentation, but I wasn’t a core member, like I was at Video In, where I was involved in every collective decision. We seriously discussed moving into the Western Front and taking over the ground floor, but thought it would be better to develop autonomously. That decision owed a great deal to Michael Goldberg, who was interested in alternative, independent media and its possibilities, as opposed to art house. The Western Front was interested in performance and had its roots in Fluxus and Dada. That was a whole new thing as well, but our identities would have been locked in together. It was a deliberate decision to maintain a storefront operation on the Main (Main Street and Powell), a decision we also based on availability and affordability.

Mike: Your earliest work has been gathered together in a loosely knit collection called the Main Street Tapes (1976-79).

Paul: The Main Street Tapes were never plotted out in advance. They came out of the fluidity of the time, which was anti-art, anti-product, anti-gallery, anti-institutional. That was the environment that influenced what I did and still do. We were not studio artists. We were not going to paint stripes in every shade and size for twenty years and then go on to horizontals for the next twenty. It just wasn’t that kind of environment. That was the conceptual art notion, to reduce art, as far as possible, down to the idea. To have an idea that is framed and mounted and thought to death before it was even produced.

My influences were artists like Chris Burden who had himself shot or Lisa Steele who examined her bruises in Birthday Suit – with Scars and Defects (1974). The personal body, the feminist body, those were important. The Main Street Tapes turned the camera on me and my friends as subjects. A lot of the tapes were in-camera edited. Most were shorts, many have been lost through time. I think there were already quite a number by 1975, when I had my first public screening here in Toronto at A Space. It’s a fluid collection, only those works that were shown more than once and dubbed and put aside are part of the mix, as opposed to the ones that were never publicly screened or never left town. Those are in storage lockers I haven’t visited in years.

Mike: One of the surviving tapes documents a series of acne treatments. 7 Day Activity (8:30 minutes 1977-2008) features a series of off-screen voices, from doctors, hectoring nags, science officers and yourself. You have all the good lines, of course. “I became a vegetarian because of my vanity.” “I’m a party boy, and you can see every party I’ve ever been to on my face.” I have the suspicion that this tape is not about acne at all, nor is it in any way metaphorical. So tell me: what is this tape about?

Paul: 7 Day Activity has been re-edited and re-mastered after thirty years. That’s because I now have a studio practice, as opposed to a production office practice. I have one full-time assistant. Part of the process of not having an agenda and mega projects that need developing, has allowed me to remaster older works, including this one. In the past, without non-linear editing, we just moved on.

There are three voices, all belonging to friends. One is the voice of authority, another is instructional, a third maternal. It concerns youth, beauty and self-reflection. It’s about having problematic skin, and hearing this surface reflected from the mass media, from your mother and friends, and from yourself. All the voices are reflections, and the camera is a reflection. Pointing my camera at something and following it is a way of claiming experience. Once the camera arrives you can’t back away from it. Hey, this is what’s happening, here it is.

Mike: It’s both a record of what is happening, and an acknowledgment of what’s newly possible in the small room the camera creates.

Paul: Mirrors and reflection, those were early and ongoing strategies for me. The idea of being able to claim personal space, that was so NOT what was going on, in terms of television. Video art was a new terrain in which you could point the camera at yourself in a low tech way that had never been available. These are predecessors to YouTube and the proliferation of digital, non-corporate media that isn’t designed to reach the lowest common denominator. We had titles at the Video In like Home Made Baby that showed someone having a baby out in the woods at a hippie commune. Making a video like that and putting it out was radical as all hell.

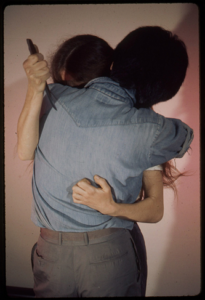

Mike: In 60 Unit Bruise (4:30 minutes 1976) you are the living tourniquet, tightening up Ken Fletcher’s arm as he draws blood out from a needle. You swab him clean, then sit backasswards in your chair and wait until he injects you with his own blood. All in a single colour shot. The camera zooms in to show a livid bruise forming. This performance art duet arrives pre-AIDS, though its shadow hovers over it all.

Paul: The Western Front had access to a colour video camera from the Canada Council for two days. I knocked out a number of pieces, of which this is the best-known, surviving piece. We wanted to make a video that would only work in colour. This is my first colour video, edited in camera.

Fletcher and I had gone to high school together, and he appears in a number of the Main Street Tapes. We had done a couple of other works that dealt with the body and blood. And we had been shooting a lot of cocaine, everyone did. There’s something really beautiful about sharing a needle — who gets to flag and who gets to wash? In 60 Unit Bruise he takes a syringe and removes 60 units of his blood and randomly injects it into my back. The different blood types result in a bruise shown in edited time. This was our blood brother ritual. At the time, Fletcher and I hadn’t been intimate. Before his death, two years later, he became my first boyfriend. He committed suicide as I slept. I woke up and saw him hanging at the foot of the bed. On the note pinned to his chest were the words, “Set me free,” a quote from Patti Smith. What role did I play or what could I have done to prevent it? Did my presence give him the strength to do it? I will never know and it doesn’t matter. I can tell you that I loved him and I know that he loved me. I didn’t speak about our intimacy for decades because we were in the closet. He had a girlfriend, I had a girlfriend, it was just something we did. So when he died, I didn’t share it with anyone. There was only space for one widow, so I stepped out of the picture. I’m speaking about it more now because the work has been re-released.

Mike: Was it shown widely at the time?

Paul: What’s widely back then? I mean really. There wasn’t a lot of wide, whatever wide is. It’s one of those works that has continued to resurface over the years. Fletcher’s imagery and 60 Unit Bruise has continued to live on with me. Thank god there has been some evolution. There’s a whole generation that doesn’t necessarily have to stay in the closet. I’m very conscious of that. When the work was re-discovered and re-contextualized because of the AIDS pandemic, it wasn’t old or new enough for me, and I was working on other things. Confused: Sexual Views had become a cause, and I had to defend it, but then I retreated and didn’t engage more than I had to. These things take their toll.

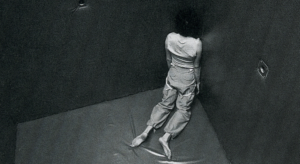

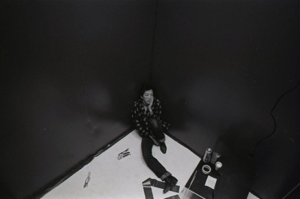

Mike: Fletcher’s death was publicly grieved in In ten sity (25 minutes 1978), a performance recorded on December 3, 1978, in front of a live audience at the Vancouver Art Gallery. The assembled crowd watched you climb up onto a ladder and disappear into a soft walled cube, 8’X8’, and then followed your actions via live video feeds from cameras that were posted on the ceiling and four walls. You circle your new room while remixes of iconic punk music play. You move in long swinging movements, crawl on the floor, circle the space, bang against the walls, lie down exhausted, hurl yourself against the walls, spit into the cameras. In the end you are joined by four members of the audience who dance exuberantly along with you, breaking up the self enclosure. The work is dedicated to Kenneth Fletcher (1954-1978), who died at the age of 24.

Paul: No one knew what I was going to do. The soundtrack is Patti Smith, the Avengers and the Sex Pistols, remixed by Al Mattes at the Music Gallery, to run the 25 minute length of the performance. The note Ken pinned to his body is from Patti Smith because he was a fan. After his death, the music we used to listen to together sounded completely different.

The performance started by me hopping over the wall. There were five cameras, one on each wall, and outside each wall were five video monitors offering an exploded view of the inside that amplified the actions. As the performance ramped up, so did the audience. They started screaming, banging on walls, throwing things inside the cube, and then some of them eventually climbed in, which I hadn’t expected. Half of them were Main Streeters. They knew about Fletcher and why I was in there, but no one else did.

The movements themselves were dictated by the cube, the size of the room, and my energy level. It actually came about one night when I was really drunk. I rolled down a long flight of stairs, got up, ran across the street and threw myself against a brick wall. I was much looser the night we went through the run-through. That was the first time I heard the musical bridges that Al Mattes had put together. I was a hell of a lot more aggressive and out of control. My original intention was to become very drugged and drunk and to rage right up to performance time with friends, but something changed just prior to the performance, and I isolated myself. I did not want to be surrounded by a lot of people, or to become totally drunk. I was on my own in that room, and had to maintain a certain energy level. It wasn’t easy to pick myself up off the floor and whack myself against those walls, it hurt like hell, but I just kept doing it. I would lay low, pogo, systematically go around the room, and then I would pick myself up again and throw myself back into the walls. The music was supposed to wipe out the audience sounds, but the room was so crowded that people stood in front of the speakers and their sheer bulk absorbed the sound. I heard the audience very clearly and I ended up responding to the audience by being more subdued than aggressive.

Mike: In 1977, a 22 year old man was stabbed to death after a house party and bled to death directly below your bedroom windows. You woke up shortly after the murder, took pictures, and later followed the body to the morgue. You clipped articles, recorded newscasts and presented it in galleries as Murder Research (1977). Can you talk about this project?

Paul: It’s a photo essay that began as a series of eighteen colour photographs that I took, showing a murder victim outside my apartment, and the subsequent research that developed out of that discovery. I followed the body to the morgue, curious about what was going to happen, but what happened turned out to be so flat and so page twelve, you know? No surprises there. I have amazing Polaroids of the body at the morgue. Was it hard to do, was it upsetting? I can’t really remember, though I was prepared to go beyond shock. I was very conscious about issues of voyeurism and exploitation. Who are these people? What happened and why? Domestic violence, love triangle, alcohol, youth, disenfranchised First Nations people. Stabbing, bad luck and regret. All that influenced the way the work was presented. Flat, non-sensationalized. It became my first gallery success, and I garnered a lot of attention as a young artist, nationally and internationally.

Mike: In 1978 you attended a ritual performance by Viennese Action artist Hermann Nitsch in a Roman amphitheatre in Trieste. You took many slides that show participants covered in animal blood and entrails, borne on stretchers, mock crucified, prostate and praying, blindfolded and nearly naked. Can you talk about this performance, and what led you there?

Paul: Hermann Nitsch had come to the Western Front in Vancouver with his Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries. I was in Europe later that year and had the choice of going to St. Tropez and hanging out with the jet set or going to Trieste and partaking in his twelve-hour performance. He was doing Christian-based rituals with musicians and polka dancing and meals, completely centered on the body. Animals were slaughtered and crucifixions staged. People came from all over Europe to engage in these actions.

I shot photographs because I didn’t have access to camcorders, and none were suitable. Up to 1986, I have thousands and thousands and thousands of slides, all of them shot click click click click. The camera is an extension of my eye, and I have the need to constantly record. On this trip, for the last two weeks, I’ve shot 900 frames on my digital camera. A lot of it will get put away, but for me, it’s an act of seeing through a framing device. It’s both practice and play.

Mike: The performance is revisited on a light table covered in slides, without words or exposition. In Trieste (5 minutes 2001) you offer equal weight to the event and its recording. Is that a way to reframe this spectacle, to change its scale and make it part of your own life?

Paul: After the trip, those slides were put away in a carousel, I think there were 120 in all. They were seen a few times over the last twenty years, until 2001 when I needed the carousel. I dumped them on a slide table where they sat for months, until one day I took out my macro lens and camcorder and started to look at them closely. I put the camera right on the slide, moving the camera and then the slides. It was my first imovie, working from materials that were dormant for 22 years.

Mike: When I started going to the Funnel, Toronto’s super-8 emporium and fringe movie theatre, Midi Onodera soon found employment there as the tech manager. I didn’t dwell on the fact that she was the only Japanese-Canadian at the co-op, but I can imagine she did. When you attached yourself to artist-run culture, were you surrounded by fellow Asian-Canadians busy making video art and performance bonbons?

Paul: It was a white scene, internationally, nationally and locally. Absolutely. But it didn’t strike me until I went to China with my mother in 1982. I remember being in Hong Kong thinking, my god, Chinatown never ends! I can’t cross the street and leave it behind.

At Video In we created our own, do-it-yourself culture. In terms of video exchange, for instance, there were many important moments. On February 27, 1973, a large group of Native Americans reclaimed the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in the name of the Lakota Nation. They held out for 71 days against the US government. Peter Berg, one of the people who attended the Matrix conference, snuck out a videotape and sent it to us, which showed what was really going on with the American Indian movement. They urged us to show and distribute the tape as widely as possible, to let people know.

There was queer performance, though they didn’t call it queer then. Feminism ran through everything. Video Inn Women’s International Exhibition (1977 and 1978), Feminist Tapes (1979) and Women’s Media Nights (1979-1985) were some of the many women’s initiatives. We were getting cameras and providing access for social justice work. I was embedded in this politic and discourse, really on the inside, so I didn’t have to proclaim anything.

Mike: You weren’t making explicitly identity-based work?

Paul: I think my identity shifted from youth to punk to sex and drugs, to queer to Asian, to Asian-Canadian. To be continued.

Mike: Did you make any distinction between video art and documentary?

Paul: My thing was always experimental and non-fiction. I never believed in the documentary for myself because I was against the voice of authority. Here is a tape recorder on a pillow on a bed, and we can both see it working… I was influenced by cinema verité, and TVTV, allowing the subject to go on. But I was never interested in creating programming, or those kind of containers. My work was never designed for that delivery system, so I never had to deliver. I could just do whatever I was doing.

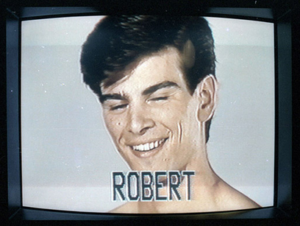

Mike: In Prime Cuts (20 minutes 1981) we watch eight people cycling on an always Sunday afternoon. They play squash, cruise on a sailboat, watch TV. They’re forever young and poreless and effortlessly glamorous. They dedicate themselves to sipping drinks and going to the gym in order to further tone already perfect bodies before shaving and primping. They lounge on the beach looking like hard pieces of modern furniture, before getting up to dance to some electrobeat pulse. They splash in the surf, wave from vintage cars, watch the TV soaps, then retire into evening cocktails with a smile that never ends. The camera floats and grazes over everything, drifting across these quick, nearly wordless vignettes. In the end each gets a solo cameo shot with their name scorched underneath: Troy, Elaine, Robert, Sheila, Paul. Who else would I ever want to be?

Paul: It had a cheap chic, documentary aesthetic. There is no second camera and no cutaways. The camera floats across the master shots as the actors enter and exit. It was taped in seven days with a ten-person crew, fully catered. I was already staging large performances, and worked as a videographer and producer for other artists. I utilized a strata of people who were involved in fashion shoots, people just getting their careers going in make-up and hair and design. That was a wonderful time when everything was possible because everyone was twenty-something, in front of and behind the camera. There wasn’t a whole lot of dialogue or scripting to create these scenes. Once we got on set, I created the scenarios and choreography. Then we improvised.

Mike: Why the all-white cast?

Paul: Paul Perri is actually south-Asian. But even in Confused: Sexual Views, which was shot two years later, I was trying to colour cast, but no one was interested. They weren’t part of my organic scene, or any other organic scene. Most of the Prime Cuts were models or waiter/actors. I didn’t know anyone like them at the time, though I do now. Everything in the tape was borrowed: the suits, the tone, the hope. I was influenced by Bruce Weber’s GQ editorials in the 1970s. Prime Cuts was a way to bring these spreads to life. I wanted to make a twenty-minute work out of a thirty-second ad, or series of ads. I was interested in taking the ad form as content.

Mike: It’s a very seductive indictment. It never looks down at its subject, but at the same time, the critique is implicit in everything they do.

Paul: But who wouldn’t want all that? It’s the west coast, man. It’s beautiful. And it was such an antithesis to what was really going on in my life. At the same time, it wasn’t that far away, either.

Mike: It signals a more general shift in video art from the raw, black and white tapes of the 70s, to work in the 80s that mimed TV. All of a sudden, Canadian video artists were hiring make-up people and actors and building sets, however threadbare and thrift store.

Paul: The buzz words I had for the tape were style, sensuality and technology. Prime Cuts marked the beginning of the 80s, and was followed up by most controversial project, Confused. This was my contribution to the sexual arena, to the problems arising from the fundamentalists, the right and the government’s fear of people being able doing their own thing. And the new possibilities VHS technology offered to control your own sexual imagery.

The first incarnation of Confused was for a 1983 performance at Harbourfront for the Video Culture Festival. I produced for the big stage because I knew I could get away with fucking and sucking and nudity because Mary Brown (chief censor for the Ontario Censor Board) couldn’t touch it. As part of the research for the piece, I interviewed 27 people, and some of this material was also used in performance, along with live projections.

Then the Vancouver Art Gallery approached me for a show to inaugurate their new space, and as I already had this project going, I thought I would take the interviews and create a piece out of that. The second incarnation of Confused was a nine-hour edit of the 27 people talking. They are shown on a series of monitors as an installation. Two days before the opening, the show was pulled. A curator had gone to gallery director Luke Rombout and said you should have a look at this, if you have any problems, we should deal with it now. The director felt it wasn’t art, and that it would offend their members. That started several years of actions and litigation. I sued them twice, and lost both times. (laughs) But eighteen years later they bought the work and exhibited it. I was not doing business with them until they came and settled. The price of the work turned out to be, almost to the penny, the same as the court costs.

Mike: When they pulled the show, was it a complete surprise?

Paul: Absolutely. This was the talking heads! It just showed people talking, the graphic material was in the longer dramatic piece. Their argument was that it wasn’t art, it’s just a bunch of people talking. How times have changed.

The cancellation was hugely covered in the press, in part because I issued a lot of press releases insisting that this was censorship. Because I had ten years of colleagues and a network, and was well versed in issues of media literacy, it was natural to address these issues, even at the age of thirty. I’ve always said that if that had been done to a less-connected artist, it would have just vanished, and no one would have heard a word.

The VAG installation invite represented a whole new trajectory for my work that their decision to cancel killed. No one touched me in this country for years. And I veered away from the gallery world as well. I was definitely black listed, or white listed, or yellow listed, or whatever you want to call it. I was definitely a troublemaker. There were some people who supported me silently for a long time, but many wouldn’t say it out loud. It wasn’t a great career move to issue a lawsuit.

The interviews were always intended as research that would be inserted into a longer narrative piece. The dramatic videotape Confused was the main project, the performance and installations were byproducts. The narrative contained nudity and graphic material, so it got killed due to the controversy around the interviews.

Mike: Confused (52 minutes 1984) combines talking head interviews about sex, TV commercials narrating gender role play, and dramatic vignettes featuring two couples who wind up in bed together. It’s as if Prime Cuts mapped out the place you aspired to, and then in this tape you went and lived there.

Paul: Gina Daniels and Gary Bourgeois were a couple, and so were Jeanette Reinhardt and I. We were high school sweethearts who continue to be good friends. Jeanette had declared her bisexuality many years ago, and so had I, and Gary and Gina wanted to experiment, as I found out. They had made the music for Prime Cuts. The four of us decided to do this project, which started out as a collaboration, but very soon it became obvious that I was the driving force and I became the director. We were going to explore the idea of bisexuality as individuals, as couples, and as a quartet, because that’s what was going on at the start of the project. By the end of the tape, forget it, the project killed everything. Once we finished shooting, the installation blew up in our faces, and there was never time to put it back together again.

Mike: Confused narrates a series of overlapping bisexual trysts: two couples experiment with same sex regroupings. At one point Jeanette, your movie/real life partner, asks, “Do you love him?” and you reply, “Should I?” Many dramatic excursions in video are painfully self-conscious, relying on narrative mechanics (lighting, camera, sets, acting) that are refused at the same time. Your winning drama succeeds, at least in part, because the camera is fluid and graceful, dialogue is kept to a minimum, and you are always interested in showing, not only telling. Along with the stylish production mode you mapped out in Prime Cuts, there is an easy naturalism to the scenes.

Paul: I always thought we looked a bit stiff but I haven’t watched it in a long time. I’ve often written for people I know. I wasn’t casting, I didn’t have time. I was developing and elaborating what was already there. It was shot two years after Prime Cuts with some of same crew people, make up and lighting.

Mike: The interviews provide a documentary punctum, weaving in and out of the coupled trysts (you and Gary, Gina and Jeanette, then all four together). One interviewee says, “One of the reasons I’m inclined bisexually is because I don’t really have more of an attachment for either of my parents.” Which you follow right up with, “My father tried to kill me when I was seventeen.” This juxtaposition strategy sometimes appears in a single statement, like this one by a woman dishing a tangle of reversals, “I couldn’t respect a man who couldn’t dominate me, and I would never be able to get along with a man that could dominate me, so I had no choice but to be with women.”

There are some very explicit scenes of people having sex – was that important? Did you feel your pre-internet resolve to show what is so usually and insistently kept hidden was a political gesture? You also insist on variety, even abundance: male-male, female-female, male-female, and male-male-female-female. It’s one big party and we’re all invited. Pleasure is important in all this, isn’t it? The pleasures of a beautiful picture, a beautiful ass, a beautiful edit.

Paul: The accessibility makes its political argument deeper. I was quite aware of making scenes beautifully lit, oiled, sexy. I wanted the straight viewer or the homosexual couple or the lesbians to be able to appreciate all of the above. Because at that time, if you said you were bisexual… what? It wasn’t a terrain that was getting a lot of respect. Now everybody’s bisexual. But the straight community and the lesbian/gay community were still trying to proclaim their own thing. Bisexuals were considered muddled, confused, triflers. The polysexual openings of Confused were the last romp before the AIDS pandemic became news item number one. How was I to know that the end of 1983 was doomsday? I now look at those interviews as a kind of utopian time. It’s like the intimacy of 60 Unit Bruise, educated people would never share needles the way we did then. That kind of touching is gone now.

Mike: Can you talk about the relation between video art and TV. Is TV the lost Eden, the electronic garden that has expelled its unwanted bastard child? Wasn’t there once a hope that one day artists would dream on TV? And when that faded away, didn’t it leave, and continues to leave, the impossible question of exhibition? Where does this work belong? Where doesn’t it?

Paul: Video In was very engaged in a McLuhanesque alternative media. There were links to other groups like Videographe in Montreal and national guerilla television. We were a group of ten or twelve people, a mix of media artists and activists, who made presentations to government regulatory commissions about television. We did performances at hearings, and circulated petitions regarding community cable. We intervened. If there was a license available, we tried to keep it from being given away. Forget about a twenty-year lease, give them a five-year lease instead. We tried to watchdog the privatization of public airwaves. There were discussions about a hundred channel universe, and satellite delivery that would make a place for new forms of non-commercial communication. When I came on the scene, cable was just developing. The fact that companies could obtain licenses to make money from channels that they didn’t pay for anyway – what did that mean? We did a lot of work to ensure that a percentage of investments went back into supporting community cable stations right across the country.

Mike: Did you imagine your work being shown that way?

Paul: I started doing installations right away. Very few of my projects were ever designed as single channel pieces. They were process oriented, performance works, multi-media works, multi-channel works, sculptural works. That’s what I had immediate access to — a live audience and space. Broadcast was not possible.

Mike: Body Fluid (22 minutes 1986) features an interlocking set of smoothly choreographed stage performances offering up divas in white dresses, a punk cheerleader, a glam presenter (presenting nothing but the gestures of presentation), a Maoist she-soldier, and a muscled young man hoisting barbells of light. How young and beautiful we are. Look at us now, quickly, before it’s too late (before I join you on the other side of the camera, condemned to watch).

Paul: There was a progression from Prime Cuts to Confused to putting on this site-specific event. I was able to get my people together into a seamless team that staged this easily and without rehearsals. We had sixteen hours and ran the performance twice, both times for a live audience. It was part of a series called Luminous Sites of ten commissioned installations around Vancouver in 1986. The site I chose was the underground parking lot for what was then the Sears building. Trucks drove onto a turntable that turned them around so they could back up into their loading bays. The turntable moved in both directions at different speeds, and the performance was designed around that feature.

Mike: It’s another one of your movies where we watch beautiful people doing beautiful things. It features both models and models of behaviour. You called it a “structuralist re-arrangement of television.”

Paul: It combines the gloss of television advertising with the look and feel of narrative. It was a scripted variety show with a mix of live and pre-recorded video and music. It had movement, cameras, live television, popular cultural iconography, but without a story. You could stand in one place and watch it turning, or walk around it.

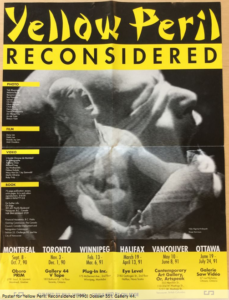

Mike: With both New World Asians (1988) and Yellow Peril: Reconsidered (1990), you organized some of the first shows of Asian-Canadian art. How did these happen? Why do you curate work?

Paul: After the release of Ordinary Shadows, Chinese Shade (89 minutes 1988), there was a personal quest to be part of a dialogue. I was looking for colleagues, and needed to see work that was dealing with the kinds of problems raised by what I was trying to do. A lot of the stuff I have produced, shown or networked is directly related to my own research, and helps create a context and audience for my own interests. I wanted to make work that was about being Chinese-Asian-Canadian, and shockingly little had been done. There were a handful of artists at best, and their work hadn’t garnered a lot of respect, attention or support. There wasn’t a lot of knowledge about it. There was no audience, no dialogue, and no community. We managed to get funding for four evenings of screenings at the Video In called Asian New World, which I co-curated with Karen Henry. The usual audience came, but more importantly, we reached out to a new audience, not necessarily in large numbers, but the quality of that audience meant that they got the work, and that was quite powerful.

A second edition happened in the UK. I developed the project to focus more specifically on Canadian work in video, film and photography. There was a gallery exhibition and a series of screenings. It was shown at the Chisenhale Gallery in East London, where it garnered a whole other reading. The community that was being represented was largely non-existent, a lot of artists had made work for the show, or work was framed for the show. I would go to people’s studios and say, “No, I don’t want to see that. What else do you have? I know you have something.” But in England the show was received as a vital import from the New World. People didn’t see it as fragmented or isolated or disparate and desperate. They understood the show as the issue of a coherent community that echoed their own dialogues around black media artists in England.

I was getting amazing reviews, and key players in the community visited. I was involved in a very intense dialogue, and from those dialogues a light bulb came on and I thought, “Let’s re-develop the show, and put it in the face of the scene in Canada.” That’s when it became a multi-faceted tour that included a book, screenings, exhibitions, workshops and talks right across the country. It was developed, produced and curated with all of my savvy. It toured with much resistance initially, but new audiences came to these events, and from there a whole sense of community developed. It was a project that took about five years in three installments.

Mike: Chinaman’s Peak: Walking the Mountain (25 minutes 1992) opens with a suite of speakers weighing in on the possible meanings and history of a mountain in the Canadian Rockies known as Chinaman’s Peak. They offer conflicting testimony which you exacerbate by appearing in the tape and offering yet another version. One thing for sure: there were groups of Chinese men up there, almost recorded in mining logs of the day. While names were entered for each white worker, the Chinese were given numbers and often grouped together under single headings like “Chink.” Were you surprised by what you found in your research?

Paul: That tape was made during a residency in Banff in 1992. I discovered that there was a mountain called Chinaman’s Peak. Why is it named that? I went to a few little archives and talked to people, and there were different accounts. There wasn’t a lot of pictures or records. It’s what I had already discovered from Yellow Peril, histories were very contingent, everything was foundation 101. The way to set the whole thing up was by suggesting possible meanings, which is a more factual way of dealing with history.

Mike: You revisit these sites with a slowly moving camera, passing broken fences and rail ties, overgrown graveyards.

Paul: I shot in Canmore and in Field, British Columbia. There are no gravesites specifically for the Chinese workers. That’s why I show washed-out gravestones, and another with “unknown” marked on it. Benevolent associations in Vancouver and Victoria had hired people to go and collect bones of the dead and ship them back to Hong Kong where they could be buried in their ancestral homeland and their souls could come to rest. In Hong Kong, there’s thousands of unclaimed boxes of bones shipped from Canada and around the world.

Mike: You make memorial gestures towards three people in the tape. The first is your father, Wong Hoy Ming (1896-1968), the second is Kenneth Fletcher (1954-1978), and the third is Paul Richard Speed (1967-1991). Both Ken and Paul appear in snapshots and home movie vignettes. Ken reveals deep cuts in his wrists, Paul grins at the door, and then is seen laid out in a coffin. I’m guessing that the only real relation between the three of them is that you knew and adored them, and that each died too early. I love this so much, that in your trying to find a way towards this impossible mountain and its impossible history, you reach back into your own life and find a way to grieve your family, your lover, your friends, and only then are able to reach out and touch this lost generation of miners. Can you comment?

Paul: My father came to Canada in 1913, either on a student visa or as a merchant’s son, of which he is neither. He was probably 14 or 15. The Chinese Head Tax started in 1885 after the completion of the national railroad to discourage the Chinese from coming to Canada, or even staying here. It ended in 1923 with the Chinese Immigration Act that banned Chinese immigration entirely, except for business people or clergy or students. That ban last until 1947, and my family is part of that whole history. My grandfather worked as a cook on the CP railways and my father followed suit, eventually finding work in Chinese cafes.

My father died when I was thirteen and he was 72. He was almost 60 when I was born, and lived with us on and off in Vancouver while he worked in Prince Rupert. He had worked in Canada all his life and went back to China every five years, sending money back regularly. He had a wife and family there, too, but couldn’t bring them over because it was illegal. He was part of a bachelor society of exclusion where people worked here for years to support families back home. They would go back, have another child, and then come back to Canada. These broken families are a direct result of legislation.

Paul Speed committed suicide in 1991. He was 24. He was a boyfriend who was also the main character in So Are You (1995). At the beginning of Yellow Peril we severed relationships because there was no place to go, and I came to Banff at the end of that project. Those three people came together for me in Banff because they all had tragic deaths. It was the first time I linked these separate events. Somehow it made sense to bury them together.

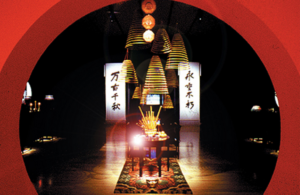

Mike: The tape closes with a man digging up a grave and setting off fireworks from inside the coffin. He transplants the bones into pots that are placed alongside candles and pyres and offerings of food. Pictures of railway workers appear in superimposition as money is being burned, along with pictures of your grandfather.

Paul: While making Ordinary Shadows, I observed these rituals and then recreated them for this tape. It came from the act of watching and recording and editing. During the funeral, paper money and clothing are burnt in the cemetery burners and a grand feast is organized so that wandering spirits are properly fed and are not tempted to claim a living substitute as a resting place. After seven years the body is exhumed, the bones are boiled and cleaned, and then a geomancer is consulted by those who can afford them, to find a well-omened place for the tomb. Tradition says that a burial can bring prosperity to the family but an ill-planned burial can lead to bad fortune.

That work was conceived, shot, rough-cut, and presented as a performance and installation, all within a ten-week period. In January 1993, I presented it as an installation at the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver. The installation included scrolls, writing, temples, mirrors, incense and photos.

Mike: In So Are You (28 minutes 1995) Narcissus makes his way towards a mirror which shows a burning newspaper with the headlines, “Scared to live here,” alongside TV clips of Nelson Mandela freed from prison, Thatcher and Reagan, street riots. After this prelude we are presented with a pair of couples: The Big Wigs are drag queens that occasionally perform in black face. Tim and Eric are twin choirboys. A series of racist jokes interrupt these portraits, this one is told twice. “What do you get when you cross a black man with a China man? A car thief that can’t drive.” The last ingredient stirred into the mix is a narrative, or at least, staged narrative vignettes, which show a businesswomen who reappears as a sex worker, while her overworked assistant becomes women of the year. How did you begin to structure this tape, with its fascinating medley of documentary and drama? Did you begin with a script, a face, a late night encounter?

Paul: The project developed out of a 1988 performance presented in London at the Edge 88 Festival called Self Winding. It was one of my huge spectacles that involved motorized mirror devices, and pairs of identical twins. I’d never been able to successfully produce a document of any of my performances, so it was developed into a script that became So Are You. It’s really late 80s work, which took five years to complete for many reasons, including, of course, the death of Paul Speed. One of the twins died of AIDS.

The title of So Are You is something a child would say: back at you, so are you. It offers a critique of the colonial impulse and models of success. A “good” black person learns to fit into what “good” already is. If you assimilate and fit in, then you’re okay. But my tape offers a reversal of fortunes and roles. If you begin at the top of the ladder, you’re bound for the bottom. All the characters get flipped. Paul Speed starts out as a fresh-faced businessman, but in his last scene he’s cranking up in a back alley. I had developed the role for him, but he then became the role, he self-destructed almost the same way he does in the script. That haunted me forever. I wasn’t sure how much I encouraged or suggested or didn’t see that. And of course I was madly in love with him.

In both So are You and Confused there’s a blurring of fiction and nonfiction. I’d known the Big Wigs for a number of years, and it occurred to me that instead of casting two female twins, it would be more interesting to have boyfriends in drag who look and act alike. They called themselves the Big Wigs and did these twinning performances, so it gave the tape one more twist. They had done black face once before, and their performance was brilliant. It would have taken me forever to say all the things that are contained within just a couple of minutes.

The twin choir boys are the Kyle brothers, Eric and Tim. One was good, one bad, one was black, one white. That’s the way they always saw themselves. Eric was a very close friend who lived in Vancouver, and I’d met his brother Tim at parties in Victoria without knowing he was a twin. They confused me for years. One was gay and one wasn’t, or so Eric thought. During the process of recording their segments they went through a gestalt where I had to send the crew away and let them at it. I have hours of recordings showing them dancing around each other, because as identical twins, Eric felt jealous of Tim, and wanted his own identity. Because Tim was in the closet, they’d never really talked about Tim being gay until the shoot started. I gave them exercises, like having them draw each other, in order to reach the places we needed to go. Eric knew he was HIV positive, but never told anyone about it. He died four years later.

Mike: Blending Milk and Water – Sex in the New World (28 minutes 1996) unveils twenty talking heads (all at least partly Chinese), each weighing in on love, sex, dating and AIDS. A series of primary coloured backgrounds offer performative or geometrical counterpoints. Your editing is often guided by beautifully contradictory or amending propositions. One couple says: “We feel very comfortable talking about sex.” The next man says, “Chinese people are more traditional and don’t talk about it.” The tape shows us that both are true, and never tries to create a final, definitive view. It is always flowing, in flux. “I had a lot of desire for men after we got married,” is followed by, “God did not intend for homosexuality to happen.” And then we hear a darkened face talk about how hard it is to come out of the closet. Here, not only are both statements true, but they are in open conflict inside a single person. Can you talk about this style of editorial juxtaposition?

Paul: This was truly a community-based project, my most outstanding and successful collaboration. It began with a gathering of a number of key people who were brought together by AIDS Vancouver to discuss how to identify, and then generate educational materials directed at, the Chinese-Canadian community. The group included ESL educators, broadcasters, AIDS Vancouver, myself, Planned Parenthood and a couple of other community partners. After a number of meetings and workshops, the result was that I would direct a media project that would take up the different concerns of the users.

I wanted to do a series of interviews using the same approach as Confused. Everyone would talk in front of a neutral background, so to speak. I had a checklist, hoping to find Mandarin speakers, Cantonese speakers, recent immigrants, Canadian-born and educated, older-younger, gay, straight and couples. I wanted to provide subjects with as many ticks beside their name as possible. They all had to multi-task. Through the network of the key partners, we found subjects, and some of the partners also conducted the interviews. Everything was transcribed into English and Winston Xin worked as my script editor. It was important that this would be watched for the entirety of its thirty minutes, so everything is chaptered with changing background colours. No one wants to watch boring talking heads. The cuts get quicker as it goes on and the coloured grids become more fragmented. When it was done everyone loved it. It was widely used, the Museum of Modern Art loved it, and it played all the festivals. It was a true community-based project that I was doing out of the goodness of my heart for a very specific aim, but it transcended all that. That’s true art. I was able to repurpose the research materials in a number of other ways, including a stage work in Hong Kong and a videotape called Miss Chinatown.

Mike: In Miss Chinatown (4:30 minutes 1997) you take the Miss Chinese-Vancouver pageant as video landscape, and allow moments of their sometimes shocking confessionals to pour through. One announces, “I was untouched and pure when I was married.” And then you add your own beauty queens: a young Asian man talks about how his desire for white guys was a rejection of his own racial background. A drug addict talks about his steady escalation of need. Voices speak at the same time while the pageant hopefuls turn in long dresses behind them. One woman (Dana Claxton) talks about her mother’s denial of her Chinese/First Nations background. A drag queen insists that women who paint their faces are also creating a painting. The last line of the tape is, “She’s trying to be something she wasn’t.” It is a complex look at identity politics, insisting that each identity is a construction zone, an artifice, but also that these structures have real consequences, and are the result of often unseen pressures, which are ideological in origin.

Paul: After Blending Milk and Water was finished, I had Wayne Yung edit each of the talking head tapes, and then we had an entire day left in the edit room. A number of years previous to that, I had been a judge at the Miss Chinatown pageant. I wanted to make an experiment, imagining a square room with four projections, using the Miss Chinatown footage as a ground, and letting the interviews float across it. That’s how the tape came to be. I wanted to work with moving sound and multiple voices.

Mike: You made another community project called Refugee Class of 2000 (4 minutes, 2000).

Paul: Refugee Class of 2000 is made up of three TV ads produced as part of the Unite Against Racism campaign mounted by the Canadian Race Relations Foundation. These ads started airing nationally in January, 2000. The central subjects are 34 Grade 12 students from the graduating class of 2000 of Sir Charles Tupper Secondary School. Tupper is in a working class, culturally diverse neighbourhood in Vancouver and my old high school. We offered the students six statements which they were asked to complete: “My name is…, I was born…, I am a refugee…, I am a… and I want to be…” They are intercut with words, graphics and images depicting racist, sexist, political and religious social unrest. The tape juxtaposes historical acts of institutionalized racism with current events.

It was a project dreamed up by the Canadian Race Relations Foundation that was a direct result of the Japanese Redress Settlement years earlier. After Canada declared war on Japan in 1941, Japanese-Canadians were forcibly evacuated into camps. The men went to road camps in BC or sugar beet projects on the Prairies or to internment camps in Ontario. The women and children were moved to six inland BC towns created or revived to house them. Conditions were so bad that the Red Cross provided food supplements. In 1988, Prime Minister Mulroney issued a formal apology and payment of $21,000 to each of the detention survivors. The Canadian Race Relations Foundation was begun at the same time as a watchdog for human rights. They wanted to go out into the community to create a series of TV ads made by artists of colour, and I was one of five or six artists across the country asked to participate.

Some of the onscreen texts are from Adrienne Clarkson, then Governor General of Canada, because she was a refugee, and it was all about who you could be. We all come here with hopes and dreams. We all arrive as refugees. What is a refugee? Legal or illegal, you’re still a refugee.

Mike: In Perfect Day (7:30 minutes 2007) you talk into the camera and bring us into your east end apartment, declaiming your happiness over cable TV, ice cream and cigarettes. You say, “I got my heroin. I got my cocaine. That’s because the heroin dealer didn’t come until two today, and I needed to get a little something going to meet up with my family at eleven. So I did some of that, the cocaine, went off to the graveyard in Burnaby, went for dim sum, came home, had the dealer drop off this, had one of these, and now I did my second one…” You file through CDs, excitedly picking out the Velvet’s Heroin, then Lou Reed’s Perfect Day. But the disc skips and stops and the wide-angle lens you hope for never materializes. You wash the disc, briefly appearing shirtless and announce, “Oh no, I hate my body. I have low self esteem in that area.” The song never plays in the end, continuing to start and stop. Perfect Day draws endless circles of hope and addiction and dissatisfaction while managing something very rare: real intimacy. But tell me: how could you bear to show this? Despite the occasional video pyrotechnics, this is a very naked exercise.

Paul: I’ve pointed the camera at myself for a long time, and in the past year I’ve been going back and recovering some of the hundreds of records I’ve made as diaristic journals. Perfect Day was recorded in March 2006 and edited the following day and then lost in the computer until we recovered it a year ago. I decided to leave it the way it was. It’s part of a new series of portraits.

Mike: You’ve always made a point of putting yourself forward as one of the subjects of your work. In Confused, for instance, you appear right alongside everyone else, dishing about sex and lost dreams. It’s a choice many directors would take pains to avoid. Why do you feel it’s important to be on both sides of the camera?

Paul: I don’t think I can ask my subjects to bare all when I’m not willing to do it. It breaks down the division between who is looking, and who is looked at. That’s why I have an open relation with my subjects, because I don’t go in there with the camera shield up. Perfect Day is just a day that is very playful, though it could be deeply disturbing…

Yesterday I had a Chinese reporter here from Sing Tao (largest Chinese daily), and she was very concerned with what people would think about the tape morally. She’s a journalist not an art reviewer. She was fixated on the idea of happiness, and wanted to know if drugs bought happiness. I was trying to steer that somewhere else, because it was framed in her morality. I asked her, “Are you happy when you said you’re not going to have a chocolate, and you polished off the whole box? Are you happy that you spent all that money and now you have that Louis Vuitton bag?” For me, abuse of drugs is no different than abuse of the credit card, it’s just a different form of abuse of the credit card. (laughs) Happiness is in the eye of the beholder. That’s what the end of the tape says, “Be happy.”

Paul Wong Videos (to 2008)

New Era Marathon (with Gerry Gilbert and New Era Social Club) 60 minutes 1974

William Burroughs Reading (with Western Front Video) 42 minutes 1974

Earthworks in Harmony (4-channel installation) 32 minutes 1974

Snack Pack 1 (includes: Sculpture and Movement, Year of the Tiger, Simple in a Complex World, Tribute to Amy Vanderbilt, Miss General Idea and the Hollywood Exhibit) 30 minutes 1975

Subway Loop (3-channel installation) 11 minutes 1975

Contact Improvisational Dance 24 minutes 1976

Amass/composite 18 minutes 1976

Gutter (with Valerie Hammer) 8 minutes 1976

Rotunda (with Valerie Hammer) 8 minutes 1976

Main Street Tapes (includes: Red, Green Black; He, She, They; Vice a Versa; K of P; 60 UNIT: BRUISE) 30 minutes 1976

60 UNIT: BRUISE 4:30 minutes 1976

Rock Garden (2-channel installation) 1976

Amass (4-channel installation) 30 minutes 1978

Three Video Dance Poems (with Paula Ross) 30 minutes 1976

Murder Research (with Kenneth Fletcher) 17 minutes 1977

Support Modelling (3-channel installation) 5 minutes 1977

7 day Activity 13 minutes 1977

In Ten Sity 23 minutes 1979

4 39 minutes 1978-80

Script (abe’s) 29 minutes 1980

Prime Cuts 20 minutes 1981

Los Popularos Compilation (includes: Don’t Say It, Can’t Come Back) 7 minutes 1982

Installation 1984 6 minutes 1984

Confused (with Gary Bougeous, Gina Daniels and Jeanette Reinhardt) 52 minutes 1984

Confused: Sexual Views Compilation Edit (with Gary Bougeous, Gina Daniels and Jeanette Reinhardt) 59 minutes 1984

Homelands (with Joolz) 7 minutes 1986

Body Fluid 22 minutes 1987

Ordinary Shadow, Chinese Shade 89 minutes 1988

FLV: Feature Length Video (with Karen Knights) 60 minutes 1989

Paul Wong: Videoclips 60 minutes 1992

Chinaman’s Peak: Walking the Mountain 25:30 minutes 1992

So Are You 28 minutes 1995

Temple of My Familiar 20 minutes 1995

Blending Milk and Water – Sex in the New World 28 minutes 1996

Miss Chinatown 4:30 minutes 1997

Born Under Surveillance (with Chris MacKenzie) 1:30 1999

Refugee Class of 2000 4 minutes 2000

Trieste 5 minutes 2001

Smash (with Winston Xin) (includes: Born Under Surveillance, Body Fluid, 4, So Are You, Confused, Confused Controversy, Support modeling, prime Cuts, Blending Milk and Water: Sex in the New World, Ordinary Shadows/Chinese Shade, Wah-Q, 60:UNIT BRUISE) 55 minutes 2002

Eat: Mainstreet Diner for the Homeless 4 minutes 2003

Hungry Ghosts (5 channel video installation) 33 minutes 2003

Perfect Day 7:30 minutes 2007

Running in a Maze 3 minutes 2007

In ten sity mix 25 minutes 2008

Dog Eat Dog 6:45 minutes 2008

East Van: John 38 minutes 2008