Work, Bike and Revolution: an interview with Keith Lock

made in 2009

Mike: Could you tell me about your family?

Keith: My father was born in Toronto and my mother, a Chinese Australian, was born in Melbourne, Australia. They met during World War Two when my father was serving in the South Pacific war. During the war, Chinese Canadians were generally not accepted for service in the Canadian military. The Chinese Community was denied the right to vote and could not own land in some provinces. There was a lot of anti-Chinese lobbying at the time, and military service during wartime would undoubtedly enable Chinese Canadians to claim full citizenship, so it was Canadian military policy to keep them out. My father and a handful of others managed to volunteer and were accepted. I don’t know why my dad got in, because my uncles and nearly all the other men and women from Chinatown were turned away.

I grew up thinking that my father had served in the Canadian Dental Corps until 1986 when a Member of Parliament, Roy McLaren, came by to interview my father for a book he was writing called Canadians Behind Enemy Lines 1939-45. We found out that he had served in British Intelligence Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.), which was the same group that Ian Fleming, the author of the James Bond novels, served in. He couldn’t tell anybody because he was bound by the official Secrets Act. It wasn’t until 40 years later that this information became unclassified.

My parents were married in Australia. After the war, my father wanted to move to Australia, but he was barred due to the White Australia Policy. My parents decided to settle in Canada, though my mother couldn’t enter the country because of the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law barred anyone of Chinese ancestry from entering Canada. My mom obtained entry through a special Act of the Privy Council. Fortunately my dad was not in any really dangerous situations during the war and the atomic bombs brought an end to the fighting just as he was about to be deployed. One or two men of his S.O.E. group did suffer from PTSD, and they subsequently had a lot of difficulties because of their wartime experiences. Because he was a war veteran, my father and his friend were the first Chinese Canadians allowed admission to the University of Toronto Pharmacy school. He opened Tom Luck Drugs in Toronto’s Chinatown in 1954. It was the first Chinese-operated pharmacy in the city, I think there was already one open in Vancouver by that time.

I started taking pictures in grade two when I received a Brownie Starflash camera as a gift from my father. My father had an artistic side that he was not able to follow. The family had a Chinese hand laundry, which was one of the lowest paying businesses around (both my grandparents basically worked themselves to early death). All the washing and ironing and repairs of the clothes was by hand. I guess working in the laundry gave him some ideas about clothing. In the 1930s, my father would go to New York and come up with his own designs and show them to a fashion house in Toronto. If they used one of his designs, they paid him a dollar or two. He saved up his money and bought a photographic enlarger. They were really poor at the time and the family was all about saving money, so he was severely scolded for this reckless extravagance. My father shelved his artistic side, and became a pharmacist after the war.

When I was seven he gave me his camera and showed me how to take pictures with it. The drugstore had a photo finishing service and he would give me outdated film to use. When I went to high school I met Jim Anderson and we did a school geography project using regular 8mm movie film. After that, my interest switched to film and my father lent me his 8mm camera and provided outdated rolls of regular 8. Jim Anderson and I shot some of our first films in the drugstore and used my dad as an actor. Looking back, my father was encouraging, but still expected me to go into engineering when I graduated from high school. I was accepted into the engineering departments of Queens and Waterloo, but wanted to do film. He finally relented after talking to one of his friends.

Mike: Can you talk about what Three Schools was, and going there with Jim, and working on movies together?

Keith: The Three Schools was a tiny art school which offered a course in filmmaking back in 1968 or 1969. It was located above a store on Bloor Street, just west of the Brunswick Tavern. Jim and I met in Grade 11 at North Toronto Collegiate. He had just moved to Toronto from Peterborough and didn’t know anyone. His locker happened to be right next to mine. Everyday we would have a contest to see who could get their combination lock opened first. Either I had easier numbers on my lock or he would let me win, because I don’t recall him ever getting his locker open first. Jim was really into photography and film and we made a film as a geography project that year. Jim’s mother was a war bride from Holland. She was a painter and had a studio in their basement. Jim’s brother Dave was the best painter at North Toronto High School and did all the event posters. It was Jim’s idea to go to the Three Schools and take their filmmaking course which happened every Wednesday after school. We had a system that he would call me up when he left his house and I would go to the subway and wait. He would jump out at my stop and then jump back onboard when we saw each other.

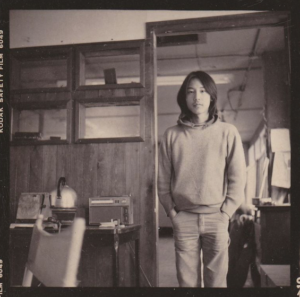

Jim Anderson on the set of Penetrated by Peter Dudar, shot at CEAC

The Three Schools film course used super 8 and the teacher was a hippy filmmaker named Iain Ewing. Iain said things like “20 minutes of black leader would tell me a lot about the inside of your head.” Most of the adults were disgusted and dropped out. Another teenager who was taking the course was a girl named Susan Conway. She was on TV in a CBC series called “Adventures in Rainbow Country.” We all became friends and she was in Work, Bike and Eat (1972) a few years later. Jim and I were about the only ones who actually used the Three School’s super 8 camera to make a film. However, when the course ended we still hadn’t completed shooting. Iain said not to worry and that we should just keep using the camera until we finished. We kept that camera for months and when we returned it the school was surprised. It turned out that Iain wasn’t teaching there anymore, he had just told us to keep using the camera. Meanwhile the people at the school were freaked out because they thought someone had stolen it.

Iain was a great mentor. His girlfriend, Clara Meyers, was soft spoken and wore steel framed glasses. Clara was the first coordinator of the CFDC (Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre) and one day Iain took us there. At that time the CFDC was in Rochdale, the notorious free university housed in a high rise at Huron and Bloor Street. All the films were in a single cardboard box which was kept under a folding table which served as Clara’s desk. Iain showed us David Cronenberg’s Up From the Drain (14 minutes 1967). Later he showed us Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls (2-screens, 3 hours 15 minutes, 1967) and we also watched parts of Sleep (5 hours 20 minutes, 1963) and Empire (8 hours 1964) but I don’t remember where that was, perhaps at the Three Schools? Jim and I finished the film we had shot with the Three School’s camera and called it Flights of Frenzy (6 minutes 1969). It ended up winning Best Super 8 at an important UNESCO competition in Amsterdam, and Jim and I appeared in all the newspapers. Jim made a hand-drawn film called Scream of a Butterfly (6 minutes, silent, 1969) that won the Grand Prize of the same festival.

At around this time The Imperial Theatre, which was the largest movie theatre in North America, was divided into six theatres, becoming the first multiplex cinema in the world. The Imperial Six, as it was then known, was just around the corner from my father’s drugstore in old Chinatown. The theatre would give my dad free movie passes if he would place a show card in his window listing all the films. My dad gave the passes to me and so every week Jim and I would go to the movies for free. We would use the same system of jumping on the subway and go together after school to the theatre. I remember seeing Easy Rider (1969), The Wild Bunch (1969), The Thomas Crowne Affair (1968), Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Goin’ Down The Road (1970), which Iain Ewing had worked on as Don Shebib’s assistant editor.

We saw lots of student films and thought most of them were crap, and a very few were great. Naturally we put our own films in the latter category. We were cocky. Since we already had a high opinion of our films, the awards weren’t that big a deal, if that makes any sense. And by that time Jim and I were pretty much a filmmaking duo, so things like awards and media coverage didn’t really penetrate into our tight-knit circle of two. Jim would sometimes joke about “the dame with the ball on her shoulders,” meaning his Grand Prix Trophy. The ball was a removable silver world globe which rested on the shoulders of a topless winged woman. This trophy was a serious piece of hardware, but Jim kept it in the back of his closet. He only showed it to me once, and that was right after he received it. Jim was introverted and he regarded the prize as equal parts burden and boon. For my part, I was able to bask in the reflected glory of the grand prix won by Scream of a Butterfly. I really didn’t have anything to do with the film, except for coming up with the title. People regarded us as a filmmaking duo and rarely referred to Jim without mentioning me in the same breath. In any case, being the co-recipient of the Best Super 8 Award wasn’t too shabby.

The awards in Europe opened doors. We were commissioned to make a film for the International Red Cross. We got jobs teaching filmmaking to young people at Theatre Passe Muraille, and we were invited to be on “Drop In,” a national television show. This program happened to be hosted by our friend, Susan Conway, although she claimed she didn’t have anything to do with it. None of this seemed strange. We were cynical and idealistic teenagers.

Iain Ewing introduced us into the Toronto filmmaking scene, which was a lot smaller than it is today. Aside from the National Film Board and CBC, films were made independently with small companies. Artists, narrative filmmakers and underground filmmakers, while not in the same bag, were much closer to each other than they are today. Jack Chambers would be considered in the same breath as someone like David Cronenberg. There were no film schools in Canada.

Jim and I both went to York University in 1969. This was the second year the film course was offered and the first year there was production classes. One day I was hitchhiking home from York after classes and a federal civil servant stopped for me. He mentioned a program he was administrating called Opportunities for Youth. This was an initiative by the Trudeau government designed to help young people. He told me the program wasn’t publicized very well, and as a result they didn’t have enough applicants. He suggested that I submit an application and told me where to send it. I did this and received a grant of $1200 to make a movie. Kodak donated free film and we had free processing done at Ryerson. I remember that after the film was finished and printed there was still a few hundred dollars left over. Jock Brandeis, a legendary gaffer at the time, let us borrow his beautiful Eclair NPR and keep it indefinitely while we were shooting. I don’t remember that he asked for any money in return. Even though we were pretty well known in the indie filmmaking scene, when I think back on it, I am amazed that he had so much faith in us. I hadn’t reached my 20th birthday and Jim was probably around 21.

Mike: Arnold (10 minutes 1970) is a post-love story about a teen drug store clerk named Arnold (what else?) and Sophie, a young, headache-prone customer looking to move into the neighbourhood. There is a playful, slapstick quality to Arnold’s presentation, as he staggers through the crowded pharmacy arms piled high with Kleenex boxes, or shooting elastics at the camera. As he mops the floor, the camera follows him, keeping him effortlessly centrered in the frame, but then takes on a mind of its own, and pans back and forth, only occasionally catching glimpses of Arnold as he does his duties. When Sophie enters and asks your father (an excellent and very natural actor, by the way) if he knows whether there’s any places to rent, Arnold drifts into the frame and announces that there is free space in his house. She comes by and he shows her a tiny set of rooms in a witty montage that has him announcing, as he opens the same door again and again, “This is the bedroom. This is the heated swimming pool. This is the whipping room.” They sit and talk at an overcrowded table, and Arnold manages to overreact to every banality Sophie offers. Comments about the weather inspire him to get up and open the window and confirm, “It’s cold outside.” When she tells him she likes the lamp he gives it to her. And when a plant blocks their view of each other he hacks it down. Eventually he shows her a gun and begins to fire away at nearly everything in the room, inspiring a tantrum of Sophie’s where she trashes the room. Where did you meet the actress, how did you decide on John Turnbull, and how did you organize the shooting?

Keith: I hadn’t seen Arnold since the 70s, but reading your description, it all came back in a rush. I’ve since had it digitized and have watched it a couple of times. I knew Penny Gawn, the actress who plays the character Dorothy, because we car pooled to York together. She was from New Zealand and was a theatre arts major. The main actor, John Turnbull, was my friend from high school. At one time I had two really good friends and both had exactly the same name: John Turnbull, although they didn’t look anything like each other.

Jim Anderson and I wrote the script, and were interested in following the logic of an idea until it became absurd. I remember one of the other students in our production group was deeply troubled by the script and complained to our professor. He just didn’t understand why the girl would come back at the end to get the lamp. Our professor, Jim Beveridge, talked with Jim and I about it and then let us go ahead. The student who had complained was eventually won over and, after the rushes were screened, he apologized to us. He also commented that he thought the footage looked like something that could be on CBC. He meant it as a compliment but we didn’t take it that way. As arrogant students, we hated the conservative and stupid films that we saw on television.

There were many reasons why we chose to shoot at my father’s drugstore. Jim and I recognized that the downfall of many student films lay in their choice of locations. Many filmmakers didn’t bother leaving the university campus so there was a fundamental lack of authenticity in these productions. Also, I had grown up working at my father’s store in Chinatown and, for me, it was a safe, creative space. It was at the drugstore that my father encouraged me to do film and photography, without my being aware of it. As I mentioned, he had wanted to do photography himself but couldn’t. He had set up his enlarger in the basement of the store and taught me how to use it. From the time I was seven or eight years old, whenever the store wasn’t busy, I would disappear into the basement darkroom. The door to the darkroom can be seen clearly in the scene in which Arnold sweeps the floor while the moving camera goes out of sync with him. Jim also felt at home at the drug store. My dad used to call Jim by his last name. I can still hear his voice calling, “Anderson, come here,” or “Anderson, are you going out for a few cold ones?” Jim had taken an apartment in a run down house just a few minutes walk from Tom Lock Drugs. This is the other location used in Arnold. My father’s partner at the store was Arnold Mark, hence the origin of the main character’s name.

The drugstore was like an open public space since it was both Chinese and Canadian. Let me try to paint a picture of it. On either end of the little block where Tom Lock Drugs was situated was the Continental Hotel, which was a centre of the lesbian scene. On the other corner was the Ford Hotel which was a centre of the gay scene. With the Greyhound bus station around the corner, the neighborhood was also full of out-of-towners. Across the street from my dad’s store was the Guangdong hotel where you could rent rooms by the half hour. Day and night, up and down Dundas Street were the chai guy nui, literally “car street women,” who worked the tourists and the bachelor society to full advantage. So much life walked through that store and I witnessed it from a very young age. However, it was never scary or strange. My father was always calm. He had been a commando during the war and his bookkeeper, David Shiozaki, had a brown belt in judo. I remember sometimes the two of them would have to escort people to the door like a couple of bouncers.

I remember while I was at York, one of the students insisting that I had to be in his production group. It turned out he wanted to shoot his student film in Chinatown. His idea was to have his girlfriend, dressed like a hooker, pose out on Dundas Street while a Rolling Stones song, Parachute Woman, played on the soundtrack. I remember on the day of the shoot, I was inside setting up the camera when the girlfriend came running in. She had been standing in front of the store having a cigarette when a man had propositioned her. She was shocked and frightened. At the time, I didn’t say a word but I was thinking, “What else did she think would happen?”

We didn’t include any of this aspect of the drugstore in Arnold. However, for Work Bike and Eat, there is a little more of the street and surroundings in the film.

Mike: Work, Bike and Eat (43 minutes 1971) opens with a thrilling, handheld camera stroll up Yonge Street, converted for the day into a pedestrian walkway. Every hairstyle and mod clothing presentation brings back the moment. Arnold, as if clinging to a bygone time, sits by his window spitting cherry pits, until the camera backs up and he uses it as a mirror to adjust his tie. He finds work (at your father’s drug store), and then has dinner with his folks where a well rehearsed choreography of passing plates and communal eating provide reliable pleasures until language separates everyone into their generational roles. There are many scenes of Arnold on his bike, and while in most movies these would appear as transitions, you allow these happenstance meetings to accumulate and become the body of the film. A hippie hipster sneers at his antique bike, a couple of young women briefly accompany him to a bridge. In both instances, he leaves alone. Quick cutting verité scenes from the drugstore are winningly mixed with staged reenactments (of a shoplifter, for example, or someone asking repeatedly for firecrackers). There is an uncanny feeling of life going on, and that the film you are making is part of that life. This is underlined by your group scenes which feature majorly overlapping dialogues. The flow and feeling tone of these scenes seems at least as important as the content. There’s a long boyish beer party that slyly introduces queer themes and ends with mutual beer dousings. Jim Murphy is one of Arnold’s drinker friends. I recall he was a pivotal person in the early Toronto film scene, an American draft dodger that leant political gravity to the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre where he worked for a while. Can you talk about meeting him?

Keith: Jim Murphy was such an important person in my filmmaking life. I remember the first time I spoke to Jim. I was still living at my parent’s home and Jim Anderson and I had finished a hand-drawn film, Base Tranquility (7 minutes, 1970). All my previous films had been done in 8mm. Since this was on 16mm, Moira Armour, who was a mentor at the Board of Education, suggested calling CFDC (Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre) about distribution. I was 17 or 18 years old, and I remember standing in my parent’s kitchen while dialing the number on the wall telephone. I was nervous, but Jim quickly put me at ease with his quickly clipped, New York style of talking. He said he wanted to see the film and asked if I would bring it to the office. I suggested a day but this didn’t work for him. Apparently the new Rolling Stones album would be in stores that day and he was going to line up outside Sam the Record Man to be sure to get a copy. Then he was going to close the office and go home to give it an “official listening” with headphones. I remember thinking to myself, “Cool!”

The Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre was called the CFDC until parliament created the Canadian Film Development Corporation, later renamed Telefilm Canada. The massive Canadian Film Development Corporation wanted to be called CFDC. It’s not surprising which organization prevailed and which was forced to change its name to CFMDC.

Jim Anderson and I screened Arnold at a special festival, I think it was in celebration of the opening of the film office of the Ontario Arts Council; film being a brand new art form. Arnold went over really well. The audience chuckled throughout the entire film and erupted with laughter when Arnold slices the plant and then begs Dorothy to stay. Jim Murphy was at that screening, and after it was over we got on the subway to ride home together. Jim promised to help us make our films any way he could. At that time I didn’t know Jim, and I didn’t really understand his deep feelings for independent films.

A little later, at York University, I overheard a classmate saying how he and his girlfriend had broken up and he was looking for a new person to live in his co-op house. I don’t know what possessed me, but I spoke up and offered to take the available room. My dad was surprisingly okay with this. I told him that it would only be for the summer, while we were shooting Work, Bike and Eat. It turned out that Jim Murphy also lived in this house, along with Kirwin Cox, another American escapee from the madness of American politics and the Vietnam War. Kirwin and Jim were both very involved in the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op and the CFDC.

I was in attendance at the first meeting of the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op at Rochdale College. This was the first film co-op in Canada, which later morphed into the Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto (LIFT). Wildly anarchistic, they designated me, in absentia, to be the co-op’s first chair. The thinking was: Keith is Chinese, therefore he should be our chair because he will be like Chairman Mao, who is also Chinese. It was a good-humoured “fuck you” to those outsiders who demanded such things as a chair in the first place. This was typical of Rochdale, which was often the first stop for young American draft resisters fleeing the Vietnam War. Here, being Asian was not a negative. If anything, it had a kind of strange cachet. Rochdale College was filled with fresh ideas and an urgent energy—both the Filmmakers Co-op and CFDC offices were located there. I taught courses in filmmaking there for the Co-op. I was immersed in all the stuff surrounding Rochdale, the incredible experimental free university, and had just turned twenty.

Hanging out with Jim Murphy was an education. He had bookcases filled with nothing but film books, all of which he claimed he had stolen or “liberated.” He had an encyclopedic knowledge, not just of Hollywood, but also the American Expanded Cinema movement. Joyce Weiland was a deeply nationalist artist who had fled New York along with Michael Snow. At that time she could be quite vocally anti-American. However Joyce described Jim Murphy as “one of the good Americans.” Jim was really a visionary. More than forty years ago, while a student in New York, he had foreseen the rise of China and was studying Mandarin at St. John’s University. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated only a few years previously and the Americans who came up to Toronto at that time had well-formed views on the kind of politics most Canadians barely had any notion of.

One time Jim and Jerry McNabb, another ex-American, told me about a basketball team in Pekin, Illinois, called the Pekin “Chinks.” I remember listening to their discussion and not feeling any connection to what they were saying. The team has since changed its name but “Chinks” memorabilia is still available and apparently a nostalgic item on eBay.

Jim loved Orson Welles, Michael Snow and Stan Brakhage, but he also was a huge fan of Bruce Lee. A lot of artists were. I remember Granada Gazelle, an artist from General Idea, telling me I had to go see Five Fingers of Death (1972). I went to see it and I was astounded to find a theatre full of white people completely mesmerized with the Asian characters and action on the screen. I felt scales fall away from my eyes at this moment.

After Jim left the CFDC he got a job working for Astral Belleview Pathe, a commercial distribution outfit. There he had access to 16mm prints of all their films. Once on Chinese New Year he got a projector and screened Bruce Lee’s Return of the Dragon (1972) in my parent’s living room. This was in the days before VCRs and DVDs, so having a film shown in your living room was a really big deal. I remember my parents invited a lot of friends and family. They hung a bed sheet in the middle of the living room and everyone watched the film. Since the screen was hung in the middle of the room, there were people watching it on both sides. The ones sitting behind the screen essentially watched the film as a rear projection. I remember that after the film was over, the women were joking that the bed sheet was really special now because Bruce Lee had flexed his muscles on it.

At this time my parents were putting pressure on me not to go into film as a career, but after this they backed off a little and they always had a lot of respect whenever Jim Murphy’s name came up.

There wasn’t any script for Work, Bike and Eat. We had already made a short film, Arnold (13 minutes 1971) so the character was there already. The story involved Arnold going out and encountering various people so we didn’t need a full script. We would make up dialogue and events on the day of shooting.

The central character, a young man named Arnold, was played by my high school friend John Turnbull. Sometimes we would take John out on the street with the camera and tape recorder and record interactions with interesting people we met. Some of the scenes were shot at my father’s store in Chinatown and we would reenact events that I remembered happening there. A lot of the time it was just the two of us making up the entire crew—one of us on camera and the other recording sound. Sometimes, like for the dinner scene with Arnold’s parents, we had to plan ahead of time and get a third crew person.

Jim was great to work with. He could come up with things instantly. When we shot the scene where Arnold cuts his own hair in his kitchen, Jim said, “Wait a minute!” He somehow knew the guy living in the building we could see out Arnold’s window. Jim asked the neighbour if we could access his roof. That’s why, as Arnold cuts hair, you can see through the window two people run out and do jumping jacks. We accompanied this scene with a Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins song so it looks like they are jumping in time to the music. Ronnie Hawkins played at Le Coq d’or Tavern which was right around the corner on Yonge Street, so it was all tied together within a very specific place.

We never had a schedule when we made this film. We’d have to plan certain scenes, such as when Arnold drinks beer and hangs out with friends, but other times I’d phone Jim or he would call me and say, “Let’s do something.” Then we’d call John Turnbull. He was working sporadically as a surveyor, so we shot whenever he was available. We would put all the gear into Jim’s mother’s car, throw the bike on top and drive around until we found a place that felt right and film whatever we encountered. This was how the scene in which Arnold meets the young toughs in the Don Valley was improvised.

Jim had the idea of shooting the scene with the grandmotherly woman. She had been Jim’s neighbour and he used to shovel snow for her. We wanted her to talk about her memories of the bygone romantic past. She had met princes in pre-World War One Europe and travelled by dog team in the Canadian north. However, when we arrived to do the shooting on her big front porch, there was a lot of commotion and noise. Outside her house a construction crew was repaving the road. They were even using jack hammers. If this had been a normal film, shooting would have been impossible. But because we didn’t have anything in our heads beforehand, we made the activities and the noise a part of the scene. The dust-filtered light and the conversation all somehow worked magically together.

Mike: In the credits you thank the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op, why was that?

Keith: Jim and I were both founding members of the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op and taught filmmaking workshops there. It was the first film co-op in Canada and we wanted to honour the spirit of this kind of filmmaking. Even though the Co-op had almost no equipment at that time, we wanted to acknowledge them. Actually the credit says “thanks to the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op in Rochdale.” We also wanted to give credit to Rochdale and to identify our film with the idealistic and revolutionary spirit of this experimental free university.

Mike: How did you and Jim make decisions together?

Keith: By the time we were shooting Work, Bike and Eat, Jim Anderson and I had been making films together for four years, almost a quarter of our lives. We had developed a short hand way of communicating that was second nature and invisible to us until somebody made a remark about it. We were very excited about cinema verité and we tried to keep spatial relationships intact during the shooting and editing of the film. An example of this can be seen in the beginning of the film when Arnold leaves the drug store on his bike, rides past the bus station and arrives outside his house. This sequence shows the entire distance Arnold actually had to travel between the drugstore and the house location. Although the camera angles change, almost no part of his short journey is edited out.

Visually, we hated the locked down, static approach to camerawork, we wanted to keep the camera moving. Some of the scenes are almost too loose and messy, but after a few minutes a style emerges. There are also moments when we intentionally overexposed the black and white film to create a visual effect.

For the beer drinking session, the camera is static at first, but starts to move in a drunken way when the characters start spraying beer. This happened because I was not used to drinking. I remember my camera work becoming wilder and wilder. Jim and I were basically a two person crew. We would switch off between sound and camera. If either of us became particularly inspired we would ask to do the camera work. When this happened it was always great, because it meant the other person saw a really interesting way to approach the subjects.

We finished Work, Bike and Eat in the summer of 1972. None of our films to this date had a properly mixed soundtrack. We would just take the magnetic tape right off the editing bench and hand that to the optical sound lab. When we were editing the film, if the sound had been transferred with the levels that were loud or quiet, we just edited the film using whatever sound level we had. For example, a shot with a loud soundtrack could be used to suddenly break into a quiet part, creating an intentionally jarring effect. We had no concept that sound levels could be mixed or otherwise altered later in a mixing studio. For this reason the original prints of Work, Bike and Eat had an audio quality that was really murky. This wasn’t fixed until several years later, in 1979. PBS wanted to broadcast the film and asked if the sound could be improved. By that time, I knew a lot more about making soundtracks. Since PBS was offering us a broadcast license fee, I found the original 1/4 inch magnetic tapes and re-transferred them all and properly remixed the sound. During the sound mix, the mixer would be trying to smooth out the levels and was totally mystified when I insisted on keeping the original “bumpy” loudness. During this whole process Jim was nowhere to be found. He was supportive and he really wanted Work, Bike and Eat to be broadcast on PBS, but this kind of film craft and meticulous approach was totally against his filmmaking aesthetic.

When Work, Bike and Eat was originally finished, it was one of the earliest produced works associated with the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op, so it received a certain amount of notice. In those days there were not many festivals where you could show independent films. It was mostly a word of mouth situation aided by the CFDC and the Co-op. The film was shown at a small festival put on by the University of Toronto and also screened by the Co-op at the Poor Alex theatre in 1972 or ’73. Filmmakers like Rick Hancox really appreciated it, and later he would teach it in his classes at Sheridan College, where it was seen by people like Lorne Marin, Phil Hoffman, Richard Kerr and possibly yourself? There was even an homage film made in the seventies titled Pulling Phones directed by the co-founder of the Toronto Filmmaker’s Co-op, Patrick Lee. I don’t recall too many screenings after the PBS broadcast in 1979. Around the time the film was finished, Jay Ledya, a professor at York University and a former student of Sergei Eisenstein, really liked it, and gave me the number of somebody in New York to call. I later confessed to him that I never rang. By that time I had moved to Buck Lake where there was no phone and no electricity.

After finishing my third year as an undergrad at York in 1972, I dropped out of school. Jim Anderson had dropped out after he finished second year, and this probably was an influence. Needless to say my parents were not happy when I followed suit a year later and blamed Jim a little. The “anarchist draft dodgers at the Filmmakers Co-op” were definitely an influence. This was the era of “tune in, turn on and drop out.” There was so much urgency in the air around the Film Co-op, Rochdale and living at the house on Roxborough Street with Jim Murphy, Stuart Rosenberg, Anna Gronau and the others. This made it very difficult for me to reconcile what was almost becoming a double life—making films in the underground/indie scene and being a full-time student at York.

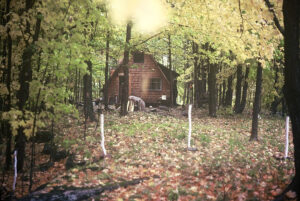

I had visited Buck Lake with some of the people living at the house on Roxborough Street. I had been totally entranced by the place itself and the possibility of creating a new society based on love, personal freedom, mutual respect and living close to nature. I had read many of Marshall McLuhan’s books and believed that my generation, the first to grow up with television, was thinking in a completely different way. McLuhan said that the new television generation will “live mythically and in depth.” This totally describes how I felt about living at Buck Lake. There was a mythic quality to the place. Anna Gronau had already moved up there.

I remember one day Tom Brouillette, the acknowledged leader at Buck Lake, had been crashing at our house on Roxborough. One day he and Anna were outside loading stuff into an old vehicle. I was standing on the sidewalk watching and wishing I could join them. I summoned my courage and asked if I could go too. Somehow, I knew that if I got in that car my life would change forever. Tom was a bit surprised, and unsure what I meant exactly. I explained that I wanted to go with them and live at Buck Lake. Tom and Anna said okay and sounded happy. I got in the truck and rode to Buck Lake.

Sometime after this Work, Bike and Eat was screened in a big room in Rochdale. I must have hitchhiked to Toronto from Buck Lake and gone directly to the screening. I remember there were a lot of people there. Everyone was sitting on the floor and the projector was on a table in the middle of the room. The film seemed to go over well. I didn’t think anything more about it until later, when I chanced upon a woman who had been in the audience. She was still an art student, and told me that she has never seen someone who was so dirty receiving so much rapt attention. In her voice was a mixture of incredulity, envy and disgust.

Mike: Everything Everywhere Alive Again (72 minutes 1974) is a nearly wordless, feature length experimentalist doc, that shows a clutch of your post-hippie friends building a barn in remote Buck Lake through four seasons. It’s all shot with a wind-up Bolex camera, so the shots are short, and usually handheld, and there is as much attention paid to the trees and sky and water as the humans. Periods of blank coloured leader often punctuate these instances of looking, and the soundtrack (never synchronous) alternates between monotone analogue synthesizer tones and field recordings. The sound somehow converts every scene into music, despite its obviously documentary qualities. Why did you start making work in this radical new way?

Keith: Much of it has to do with meeting Michael Snow and being exposed to the experimental and expanded cinema movement. Through Mike I also met Joyce Wieland, his wife at the time. Before I met them, I remember seeing Wavelength in a large university class. In his introduction to the film the professor said something like, “I have to show this film because it’s on the course.” With this kind of set up, it’s little wonder that students started booing, hissing and throwing wadded-up balls of paper at the screen. I vividly remember watching Wavelength with its slow, inexorable zoom, while other students jeered and hurled things at the screen. This was a profound moment. The derision of the professor and students only enhanced the experience, providing a perfect context for me to see it. I felt the film speaking directly to me, I think the hairs on the back of my neck were standing up. This incident illustrates the alienation I felt and influenced my decision to drop out of film school after completing three years of a four year course.

Jim Murphy showed us New York Ear and Eye Control (1964) and Dripping Water (1969) at the CFDC. When Mike and Joyce came up to Toronto from New York, it was Jim Murphy who introduced me to Mike. Mike was shooting Rameau’s Nephew (1974) and asked if I would be a background performer. All I had to do was sit in a bus and pretend to be a paying passenger. Mike was working all by himself and was having trouble setting up his tripod in the aisle of the moving bus. I got out of my seat and helped him set up the spreader and mount the Bolex camera. After that, Mike asked me to help in a number of capacities.

Today, it’s hard to imagine the intellectual environment Mike was working in. I remember being on the set shooting one of the scenes in Rameau’s Nephew. We were in a really seedy hotel room, above a tavern. Mike Snow had hired a professional cinematographer. I don’t recall the elements of the scene, but I remember the total lack of respect he received from the “professional” whose attitude was that Mike was a complete amateur who didn’t know what he was doing. Mike is very clear about what he wants and does not suffer fools lightly. I recall there was a clash on this set. The cinematographer’s condescending attitude was pretty common in those days because there were no film school graduates working in the “industry.” In fact, Jim Anderson and I had been in the very first university production class ever taught in Canada. I can still remember Mike’s reaction one day when I brought up the topic of the National Film Board. He said indignantly, “Oh they really know how to make films! They know it all!” I believe, when he first came back to Canada, he had taken a meeting with an NFB producer, but his ideas had not been received very favourably. For his part, Mike thought the entire notion that film was an industry was totally ridiculous. As far as he was concerned, film was Art with a capital A.

Sometime after the Rameau’s Nephew hotel shoot, Mike was looking for a new cinematographer. I think Jim Murphy suggested Jim Anderson and I as possible candidates. I remember showing him Work, Bike and Eat at the Film Co-op. He dutifully watched the film and I got the impression that he thought it was okay, in a conventionally narrative way. We were really eager to work with Mike. I remember blurting out, “But this is not what we’re into now… we want to make different work.” In the early seventies, the term “experimental” wasn’t totally accepted by artist-filmmakers. Mike used to call the kind of films he made “underground films.” He didn’t warm to the “experimental” term at first because he thought it carried the connotation that the filmmaker was merely experimenting, and not really serious. In the seventies I shot quite a bit of film with Mike. Besides Rameau’s Nephew, I was the cinematographer for Presents (1981), an installation piece Two Sides to Every Story (1974), and the photographic book Cover to Cover (1975).

I fondly remember working and hanging out at the house Mike and Joyce shared with their cat Dwight on Summerhill Avenue. The house was near the railway tracks and trains would slowly rumble past from time to time. Sometimes Mike would take me down to the basement to show me models of new sculptures. They would often have visitors and I remember meeting Pierre Théberge and chatting with a First Nations activist who was trying to stop the Great Whale dam project in Labrador. Sometimes we would just watch TV. They sort of took me into their world. Mike insisted that I just call him Mike, and explained certain ideas in art in an unpretentious and direct way. They were both very open and sometimes they would ask me about Chinese things. I remember Joyce used to read the I Jing (I Ching) as did a lot of artists at the time, and Mike once quoted the first words in the Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching) to me, “The eternal path does not have a name,” remarking on how profound that line is. Mike once told me that watching films was like going to church in the sense that you sit with a lot of other people and think deeply about things.

A lot of this was going on at the same time I was making Everything Everywhere Again Alive and was very influential. The film took three years to make. I originally intended to document the things that people were doing in the process of living closer to the land. I bought a used Bolex camera and would get short ends and outdated stock from this guy who lived in a high rise building near Yonge and Wellesley. In the process of shooting and editing the film, I started thinking in a different way about what I was doing, the process of filmmaking, nature and people’s lives. The Bolex is run on a clockwork motor that you wind up and then get about 30 seconds of filming. When I edited the shots together, I realized that something was missing. I was thinking about how the time spent rewinding the camera in between every shot might be represented. After all, life is a function of inhaling and exhaling. Similarly, we show the film and then we have to rewind the film. I started adding space between the shots which also helped to frame each shot as a basic communication unit, like a word with which complex meanings could be constructed. The film is about mystery and subtle effects.

I was influenced by Joyce Wieland’s use of superimposed words on images in such films as 1933 (1967) and Sailboat (1968). Since the superimposed words appear to sit on a different plane above the live action image, there is a constant dialogue between these two visual elements. One of the things I was concerned with about shooting a feature film completely handheld was eye fatigue. I found by using a small, stationary word or graphic, superimposed onto the footage, the eye can find a sanctuary where it can rest. I also discovered that when the audience is staring at a motionless word, as the scene behind it changes, interesting effects happen because it acts as a counterpoint, a stationary island in an sea of visual changes.

After shooting a year’s worth of footage, I started living in a tipi which I built from plans in a book. I was reading Dao De Jing and thinking a lot about the minimalist concepts of something and nothing. This is the conceptual framework which manifested itself in the use of blank frames of pure colour in between the documentary shots. One of the symbols I used in this film is a small circle which is the letter ‘O’ created on a typewriter. I used this because, as zero, it is the symbolic signifier of nothing. As a circle, it also signifies the cyclical seasons and the idea of completeness and totality. The theme of something and nothing is central to the film. We see pigs mating followed by a blank domino followed by a domino with a single dot. The pig licking the goat’s ass doesn’t distinguish between shit and food. It is all food.

The moment when the pig is slaughtered is an important and powerful one. We grew and bred a few pigs, but being city folk we knew nothing about slaughtering them. We had made the mistake of naming the pig and treating it almost as a pet. We took the pig to an old farmer, George Short, who became a mentor and showed us how to live with the land. George had been a lumberjack and could whittle an axe handle from a tree branch. He knew everything about horses and the intricacies of harness and tackle. He routinely used expressions which were earthy and foul. He would go on benders when he would not draw a sober breath for a week.

We took our pig to George and he showed us how to slaughter it. Apparently the best time is while the sun sets, which imparted a ghastly red light to the scene. It was our job to hold the pig while George cut its throat. I filmed the whole thing and George was angry about this. Slaughtering animals is something solemn and not something which should be filmed or turned into a circus, but he always said we did our farming with a pencil. On this day we learned something important about living.

I was reminded in a recent conversation with Anna Gronau about our visits into town, and how locals considered our style to be extreme and outlandish. We would enter restaurants knowing we might not be served. Because of this, I was surprised when we were in town one day and a grey haired woman called us over to her porch. She held out a pot of beautiful African violets to show us. I always traveled with the Bolex camera and asked if I could take her picture. In those days nobody had a movie camera. She assumed that it would be a snapshot. She stood completely still while I rolled off twenty seconds of film. There is a quiet dignity to her portrait.

The same thing happened with the other portraits of people in the film. I would ask if I could take their picture and they would hold very still while I rolled film. They were expecting a momentary click, but instead they would hear this whirring sound. They are often caught looking into the camera lens, slightly off guard and waiting patiently for the camera to be shut off. I think this is what gives their portraits an unusual and touching quality.

The film is mostly wordless and when the words do come, the relation between words and things is broken. I didn’t want to have conventional narration, yet there were times when very sparse word sequences were appropriate to offer impressionistic bits and details. The sequence about picking blueberries relates a story about being alone and finding myself face to face with a young deer. I was startled. The deer was also startled. We both froze and looked at each other for what seemed like an eternity before the deer turned and ran off. This sequence is my attempt to convey the feeling of the whole world stopping and momentarily turning upside down with fear, the adrenaline rush of my fright as I watched the deer running off, leaping across the rocks with its white tail lifted high. If I had depicted this event in a conventional way, it would have sounded mundane instead of what it was, an unexpected encounter with the mysterious.

Making Everything Everywhere Again Alive was a discovery, a defining for me of what it means to be a Canadian. As a Chinese-Canadian, I felt my authenticity as a Canadian was routinely under scrutiny; even though, with the exception of the First Nations peoples, everyone in Canada is an immigrant. I would ask myself, “What is the source of ‘Canadian-ness’?” The answer I arrived at was nature. At Buck Lake we lived in nature and got to know it intimately. In some respects, making the film was like tapping into the bedrock of Canadian culture and identity. It’s interesting that even without knowing anything about my background, audiences pick up right away on an Asian quality running through the movie.

I don’t think I knew who would watch the film. I guess I made it for anyone with eyes and a heart. It premiered at the Pacific Cinematheque in Vancouver and was reviewed in Parachute and Cinema Canada and it got a larger than usual audience whenever it screened at the Funnel. It was my hope that the film would be able to be understood by people who did not have an experimental or art film background. I remember leaving the film with the film librarian at a small city close to Buck Lake and getting a note back from her saying that if it was edited it could make a nice ten minute film. However, in the art film and academic worlds it did get a pretty good response and Everything Everywhere Again Alive was screened at TIFF as part of the retrospective of Canadian film in 1984.

Mike: Keith, your beautiful description of Buck Lake makes little mention of the people there, apart from George the lumberjack. Could you talk about the folks up there and how the revolutionary dream of living mythically actually worked?

Keith: To understand the mythic structure of Buck Lake you should have an inkling of the early seventies counterculture. The late sixties and early seventies really were revolutionary times. People were disillusioned by the old ways of thinking, not just in relation to a few things, but in the totality of their lives. The Vietnam War was consuming the lives of young Americans and there was a huge divide between generations. Concepts of what was masculine and feminine were undergoing shifts and some people were trying to shore up the divide between the sexes while others were tearing it down. For the first time, men wore their hair long and unisex became a word and a fashion. The sexual revolution was ongoing and in full flight.

Slogans expressing revolutionary or countercultural thinking were woven into the fabric current thought. There was, for example, “Girls say yes to boys who say no,” and I remember when I was about sixteen I caught a glimpse into my friend’s sister’s bedroom where she had taped up a poster that said, “If it feels good, do it.” While I was at York there was a widely displayed slogan “Continentalism is Treason,” a manifestation of the rise of Canadian identity consciousness. Others examples include: “Wage peace,” “Suppose they gave a war and nobody came?” “Don’t trust anyone over thirty,” “Make love not war,” etc. I remember once in the late sixties, my dad brought home a man from the electronics shop near the drug store to fix our stereo. After he left my mother said in a mildly shocked tone, “Tom, I think that man is a homosexual!” My older sister gently chided her. “Mom, it’s not who you love, it’s that you love.” These kinds of spare aphorisms shaped and reflected a new way of thinking.

During this time period, the Vietnam War was constantly going on in the background. American television cameras had unrestricted access to film American troops in action. Every night on the TV news we saw the American military doing things that would never be permitted to be seen today. I was genuinely disgusted with the war, and the capitalized sectors which profited hugely from these horrors.

The question was: how do you get outside the system? Overthrowing the established order was talked about by a few, but the real and lasting revolution was going on in people’s thinking. Among ourselves, we would sometimes ironically refer to Buck Lake as a “hippy commune,” usually to mock the mainstream media and their stereotypical images. The idea at Buck Lake was to get people together and build our own society the way we thought things should be and which made sense to us. There was never any manifesto and we never tried to discuss or define it, but we just knew who we were and what we were about — no possessions, love, sharing, honest physical labour and staying close to nature. Since a number of us were visual artists and filmmakers, experimental art practice could be added to this list.

I’d like to paint a picture of the physical and, perhaps more importantly, the psychological setting of the place. On a one hundred acre tract of forest on a remote lake in the middle of a new growth forest, one shore of Buck Lake—where the house and building stand—is limestone and on the other side is the beginning of the rocky Canadian Shield. A journey from the house on Roxborough Street would take between six and eight hours to hitchhike. It would start out on a huge eight-lane highway and descend through a series of smaller and less-travelled roads.

Roadways are part of the visible physical structure of society, and these gradually disappear on the journey. The last two kilometers are taken on a footpath so faint it can barely be seen as it winds into the deep forest. Arriving at Buck Lake, one has the feeling of having passed through the perimeter to the outside of the complex web of society and civilization. It was an immersion in a different time and a new reality in which, once again, horses provided motor power and wood was fuel.

Buck Lake, and the life it entailed on the fringes of society, always held a strong element of adventure for me. I remember the first time I went there with Tom Brouillette and Anna Gronau, we drove up with a lot of stuff which we had to hump in on the trail. Tom decided to take a short cut down a dirt road through an adjacent field. This was a road he had been warned not to use by a very hostile rural neighbor. To avoid being spotted we drove in and out in darkness. When we were leaving, the old pickup truck skidded in the dark off the dirt track. Getting out of the truck to take a look, I saw the truck’s back wheel was hanging useless, spinning in mid-air over a ditch. The sky was already starting to streak with light in the east. The situation was really tense for all of us. Short of physically lifting up the truck and setting it back on the road, there was no way out. As soon as the sun was up, the owner would find us. Tom, a boilermaker by trade, called me over to a wooded area and asked me to find something we could use for a lever. I picked up part of an old fallen tree but it was too rotten. Tom dragged a perfectly-sized piece of dead spruce tree back to the truck. He then found some large flat rocks to use as a fulcrum and we actually lifted the back of the truck up and onto the road. As we drove away, we were all indescribably relieved. The sun was coming up and Tom couldn’t resist rolling down the window of the truck and shouting out with joy. I was amazed by Tom’s demonstration of practical knowledge and I found myself eager to acquire knowledge of these same principles of mechanical empowerment.

We all learned from each other. Under Anna Gronau’s influence, Tom discovered reading and devoured the works of Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and the Beats. In the mid-seventies, after living so long among artists, he decided to become a dancer. Tom danced with Robert Desrosiers, Danny Grossman and other top Canadian choreographers of the times. Today, Tom is one of a very few professional dancers still working in their mid-sixties. He is also the only dancer in the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers.

Tom started Buck Lake with Rob McHenry the year before I arrived. They met on a construction job and hit it off, often talking about their dream of living off the grid. Not long afterwards, they began floating the lumber down the lake and building the cabin where they stayed the first winter. Rob was closer to a hard-core survivalist in his philosophy than the rest of us. Once, after cutting his hand badly with an axe during the first winter, Rob sewed up his own hand using a needle and thread. Unfortunately this got infected and he ended up going to the hospital anyway. After Anna appeared on the scene, Rob and Tom had a falling out. Perhaps it was a case of “Wedding bells are breaking up that old gang of mine.” One day Rob solemnly saddled up his mare and rode away. He had made a kind of travois with wheels onto which he packed all of his belongings. Riding his horse along the shoulders of the Trans-Canada Highway, he found his way to Calgary. He is still there today, working as a professional rodeo rider, horse trainer and racing car driver.

Jim Gronau was Anna’s brother and was seventeen when he came out to Buck Lake to stay. Jim was very interested in organic farming and had previously worked at the famous Filsinger’s farm. He was a radical and completely opposed to the food industry. I remember being in a grocery store with Jim when he picked up a loaf of Wonder® bread off the shelf and squeezed it down to the size of a deck of cards, to demonstrate how little fiber there was in it. Lecture over, he then put the now compacted Wonder® bread back on the shelf before leaving. The first time I met him it was in the middle of a very cold winter and he came out with a friend who also worked at Filsinger’s organic farm. His friend eschewed the use of all metal because of the environmental impact of metal production. I remember he had made a kind of hammock device which he strung between two trees and wrapped with a quilt and this is where he slept at night.

There are incidents I wish I could tell you about. Let’s just say some of us were a little more revolutionary in defending Buck Lake from, for example, strange voyeurs from outside, than some of us care to admit today. My apologies for this tease. Suffice it to say that we were living the dream and fully committed to it. We slept when we were tired, woke when we wanted to, drank when we were thirsty, and worked very very hard.

It was not uncommon in those days to hear someone’s mother say about her son, “Oh, he’s hitchhiking to Vancouver to find himself.” At the time this notion of finding out who you are and what you believe in was part of being young. This became a cliché spouted by “weekend hippies,” but it was also undeniably part of the Buck Lake subculture. I think we were all open to ideas, and trying to define for ourselves our own personal and essential truth.

I remember one time while we were building the barn, I happened to be at the house with David Anderson. From our vantage point the others could be seen in the far distance, carrying heavy wooden beams over to the building site. Dave and I watched them for a while, both of us lost in our own thoughts. Finally David broke the silence to announce, “Everybody carries a burden. You either help them with their burden, or you fuck off. That’s all that matters. Anything else you do or say is static, and they just don’t need it.” I remember Dave’s spontaneous flash of wisdom to this day.

There was a very strong element of what I can only describe as “personal philosophy” at Buck Lake. We were all transplanted city kids who craved authenticity. To us “authentic” meant someone like our mentor, old George the lumberjack. George, who was in his late seventies, would sometimes admonish us by saying, “Come down out of your summer cottage.” We would try to talk like him and repeat things he said. “He’s so cheap he wouldn’t spend five cents to see Jesus riding a bicycle.” “It tasted so bad I had to lick a dead dog’s arsehole to get the taste out of my mouth.” George once described his neighbor as a rich man because he had two years of split firewood stacked in rows outside his house. Another time he had an argument with his wife, Phyllis, and threw an old box of dynamite in her general direction. Phyllis was not to be intimidated. She threw the dynamite right back at him saying, “You can’t scare me. You need caps and a fuse.”

I should mention that at Buck Lake privacy did not really exist. The cabin was one big open room with sleeping lofts. Wearing bathing suits when going for a swim was a foreign concept. On a hot day both boys and girls would take off their shirts to stay cooler while working; it didn’t matter because no one else was around. Back in those days it was unusual for unmarried people of opposite sexes to live together and the local people used to wonder about us. Once when we were at George’s, he gave Tom something, I don’t remember what it was. It might have been some food he had grown and George told Tom to share it with me. Tom said he would, adding, “We share everything.” In a sly voice George asked, “Does that include your lovin’ too?” Tom, who could be really good at expressing much using few words, simply replied, “That’s not mine to share.” At Buck Lake we tried not to be possessive in our relationships with others, but as is shown in the film, this didn’t always work out happily.

In this spirit of searching, the core group at Buck Lake discovered Primal Therapy. This was something extolled by John Lennon and was apparently intrinsic to his album Imagine (1971). The basic idea is that at some point everyone unavoidably suffers a deep emotional hurt. This might be caused by a parent or someone else, but it is part of the inevitable process of becoming an individual. In Primal Therapy people work to remember these events and when they do they emit a “primal scream” which is spontaneous and comes from deep inside their being. I didn’t have anything against this, since people said they really benefited from it. But it wasn’t for me.

Practicing Primal Therapy meant sinking into your feelings which could mean letting out screams and words and sometimes crying. It was ironic that a place of peacefulness was becoming the scene of so much noise. I started feeling that I had to escape. Jim Anderson, who was not at Buck Lake all the time, had built a little hut along one of the trails which he humourously named the “screw shack” after something in a Jack Kerouac novel. I had been reading The Indian Tipi by Reginald and Gladys Laubin and decided to build a tipi for myself to live in. I bought painter’s canvas at Gwartzman’s and cut cedar poles for it down by the lake. Before cutting each tree I said a little prayer. A few years ago, the poles were donated to the Canadian National Institute for the Blind and are still in use in the children’s garden. Living in the tipi was like living in a soaring cathedral, it was a sublime structure. Anybody who visited the tipi would comment on how special it felt. I wanted to see four seasons from one piece of land so I lived there for more than a year.

I guess the question that arises is: did our revolution based on love towards all, scarcity of possessions and living close to the land, fail? Was it all just an illusion? In the beginning we took delight in working together and learning from each other. Gradually the idealism (or perhaps it could be called ideology) began to slip and we got into other things and drifted apart, sliding back into the ways of bourgeois society which we formerly scorned. Even Tom and I had a terrible falling out in the late seventies, but an unbreakable bond still existed. Years later he called during a personal emergency, simply needing my ear. Needless to say I was very moved, and we’ve been close friends again ever since.

The five years I spent at Buck Lake were extremely formative in my thinking about the true nature of people and the nature of, well, nature. To this day I am still working out the meaning of my thoughts and experiences there. Sometimes I would not see another human being for days. With the nearest road a long hike away, I learned to be very mindful of what I was doing since one slip of the axe could mean the end.

Tom’s daughter Mai was a teenager in the mid-nineties, and was part of the punk scene around Kensington market. One day she told me she thought her dad’s revolution had failed. But I don’t think our revolution failed, it simply evolved, as did the people in it.

Mike: You haven’t breathed a word about love yet. Did it never happen? And did that falling (curious term we have for it) not affect your movies, your seeing, your hopes for cinema and for the revolution that you and your comrades were busy living?

Keith: Yes I did fall in love, with Leslie Padorr. Stuart Rosenberg told me about this girl at the film co-op and said she was beautiful. Usually my friends would describe a girl as cute or good looking, but never beautiful. I was curious enough to turn and look back at her once during a co-op meeting at Rochdale, but I was far away and couldn’t really see anything special.

Back then there was a collective called Third World Newsreel which produced and distributed counterculture and politically alternative films. Newsreel was based in New York and had recently opened an office in Toronto. They asked me to cover the occupation of a building by students at the University of Toronto. At the time Newsreel didn’t even have enough money to buy film. They just wanted someone to be there with a movie camera, to keep the police honest. The occupying students had turned an empty campus building into a daycare centre, needless to say without permission. I think they had tried to negotiate through regular channels but this had gone nowhere, and now the University was trying to evict them. In the midst of chaos and chants of, “I care, you care, we all care for daycare!” I met Leslie for the first time. At the time she was still married to Jerry McNabb, the coordinator of the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op. Leslie and Jerry were going through the process of breaking up, and sometimes Jerry would crash with us at Roxborough Street when things got too difficult at his place. Leslie and Jerry had a two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Mona.

After the demo, the next time I saw Leslie was at the screening of Work, Bike and Eat at the Poor Alex theatre in ’72 or ’73 and I remember talking to her there. She told me later that this was when she decided she wanted to hang out with me. I think Leslie knew Anna and one day they came up to Buck Lake together. Jerry later gave me a photo he had taken of Leslie and me at the demo the day we met. He and I worked together on a couple of commissioned documentaries in the seventies, so it was fairly amicable.

I’m not really clear about how falling in love might have affected the films I made, or the “revolution” at Buck Lake, but I think it was possibly profound. Perhaps this was another reason for the withdrawal from the group on my part. I remember arriving at Buck Lake after hitching from the city and finding the loft tidied and even my boots were hung up. It gave me a strange feeling, like I was coming home for the first time. I’m a person who really needs a stable relationship. With all the people around and all the moving back and forth, I needed to know for sure where I was going to be sleeping at night.

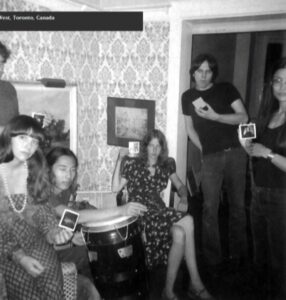

R-L Lily Eng, Peter Dudar, Keith Lock, Leslie Padorr, Diane Boadway

I moved back to Roxborough Street in ’74 or ’75 to finish Everything Everywhere Again Alive and Leslie and Mona moved in with me. After the film was finished I got mono and was feeling a bit lost, possibly suffering “completed film let-down syndrome.” My parents wanted me to return home. I don’t know how they felt about Leslie. From their perspective she was divorced, American, lofan, and had a kid already; but they were always polite to her. Leslie got a job working in Robarts Library and began studying Chinese. She took off to Taiwan for half a year while her parents in Chicago took care of Mona. I moved out of Roxborough and into a studio on the corner of Queen and John, shooting and editing the short film Parade (5 minutes 1977). It was very difficult living there by myself. The year was 1976. The rent was cheap, but it was one of those studio buildings where you weren’t supposed to actually live. I slept in a hammock which I would take down during the day, so nobody could tell I was living there. Leslie was still in Taiwan when I moved into another studio at Adelaide and John Street, above Freud Signs. This is where David Anderson and I started the New Films screenings, which was a precursor to the Funnel.

By the time Leslie came back and we were all reunited with Mona, she spoke pretty good Mandarin and could read a newspaper in Chinese. This seemed to help win over my parents. Now when we would go to Chinese restaurants, they could rely on her to translate the daily specials for them. Being born in Canada and Australia, my parents could both speak Chinese, but they could not read or write it.

One day my mother casually suggested that Leslie and I should “formalize our relationship.” After living together for six years, we were thinking along the same lines and we were married by a justice of the peace at old city hall in 1979. After the ceremony was over we reminded each other that, “It’s only a piece of paper.” By which we meant, what really matters is the feeling in your heart. We try to give each other as much space as we need, and we’re still together.

Films and Videos

Flights of Frenzy (with Jim Anderson) 6 minutes 1969

Touched (with Jim Anderson) 8 minutes 1970

Base Tranquility (with Jim Anderson) 7 minutes, 1970

Arnold (with Jim Anderson) 13 minutes, 1971

Work, Bike and Eat (with Jim Anderson) 40 minutes, 1972

Everything Everywhere Again Alive 72 minutes, 1974

Going 5 minutes 1976

Parade 5 minutes 1977

Jeannie Goes Shopping 23 minutes 1981

The Highway 35 minutes, 1983

Chinatown 25 minutes 1984

A Brighter Moon 25 minutes, 1986

Small Pleasures 86 minutes, 1993

Tough Bananas 23 minutes, 1997

The Road Chosen: The Lem Wong Story 25 minutes, 1997

The Dreaming House 6 minutes, 2005

Re:Gifted 1 minute, 2006

The Ache 83 minutes, 2009

Conversalon with Keith Lock

Saturday January 13 6pm

680 Queen’s Quay West, TO, ON, CA

Relics of Love and War (40 minutes 2023)

Keith Lock, the first Chinese-Canadian filmmaker, returns with a new movie, Relics of Love and War (40 minutes), a family thriller that was kept under wraps for decades, until the Official Secrets Act allowed these true stories to be told. Using a suite of stunning 35mm photographs, Lock brings to life intimate details of his father’s Second World War forays in Operation Oblivion, along with the anti-Chinese racism that was behind the passage of more than a hundred laws that expelled Chinese workers, stopped families from reuniting, assigned seating on public transport and theatres. Here, the smallest gestures carry a nation-wide significance.

Introduction

I think without Keith Lock it’s hard to imagine that many of us would be making movies at all. It’s not just because he’s the first Chinese-Canadian filmmaker in the country, but he showed me that you could be a filmmaker and still be a very sweet and shy, soft spoken guy melting into the background. Keith was an invitation, a door opening in a city that was built without doors.

In 1954 his father opened Tom Luck Drugs in the old Chinatown on Dundas between Bay and Elizabeth. He gave Keith a camera to make photos when he was a kid – the drugstore had a dark room he could use – and this led him to make movies in high school with his best pal Jim Anderson. On Wednesday evenings they would go to Three Schools, a small art school at Bloor and Bathurst, to study film, and they borrowed a super 8 camera to make Flights of Frenzy, a snappily cut anti-war short that won the award for best super 8 film at a festival in Amsterdam. Their win was a sensation, written up in all the papers. The two teenagers were commissioned to make a film for the Red Cross, and Keith made his debut on national TV as a guest on the show “Drop In.”

In 1969 they made a short drama that looked like a documentary, set in Dad’s drug store of course, featuring a drug store worker named Arnold. A couple of years later, with the same actor, they made Work, Bike and Eat, a 40-minute movie that feels like it’s being filmed while life is happening. Verité scenes from the drug store mix with staged encounters. It managed to be both casual and precise, a revelation.

In the 70s, which in Canada was really the 60s, Keith joined an artists’ commune at Buck Lake. He went to Gwartzman’s Art Supply which is still there on Spadina and bought a roll of canvas to build a tipi that he lived in. For the next 3 years he shot little bits of everyday this and thats with his wind-up Bolex, and made a feature-length, impressionistic, nearly wordless diary masterpiece called Everything Everywhere Again Alive that has appeared in various poobah’s greatest Canadian movies of all times lists.

He went on to make dramatic shorts and features like The Ache (based on the Shakespearean family life of Toronto poet Louise Bak) and Small Pleasures about a couple of young students who come to Canada from China). Small Pleasures was the first Chinese-Canadian feature made by a Chinese-Canadian, and it was made in 1993. That’s not a glass ceiling, it’s concrete.

Tonight, we’re going to watch Keith’s latest film, Relics of Love and War. It’s 40 minutes long and premiered at the Reel Asian Festival a few months ago. When it’s over I hope he will grace us with more of his masterful storytelling.