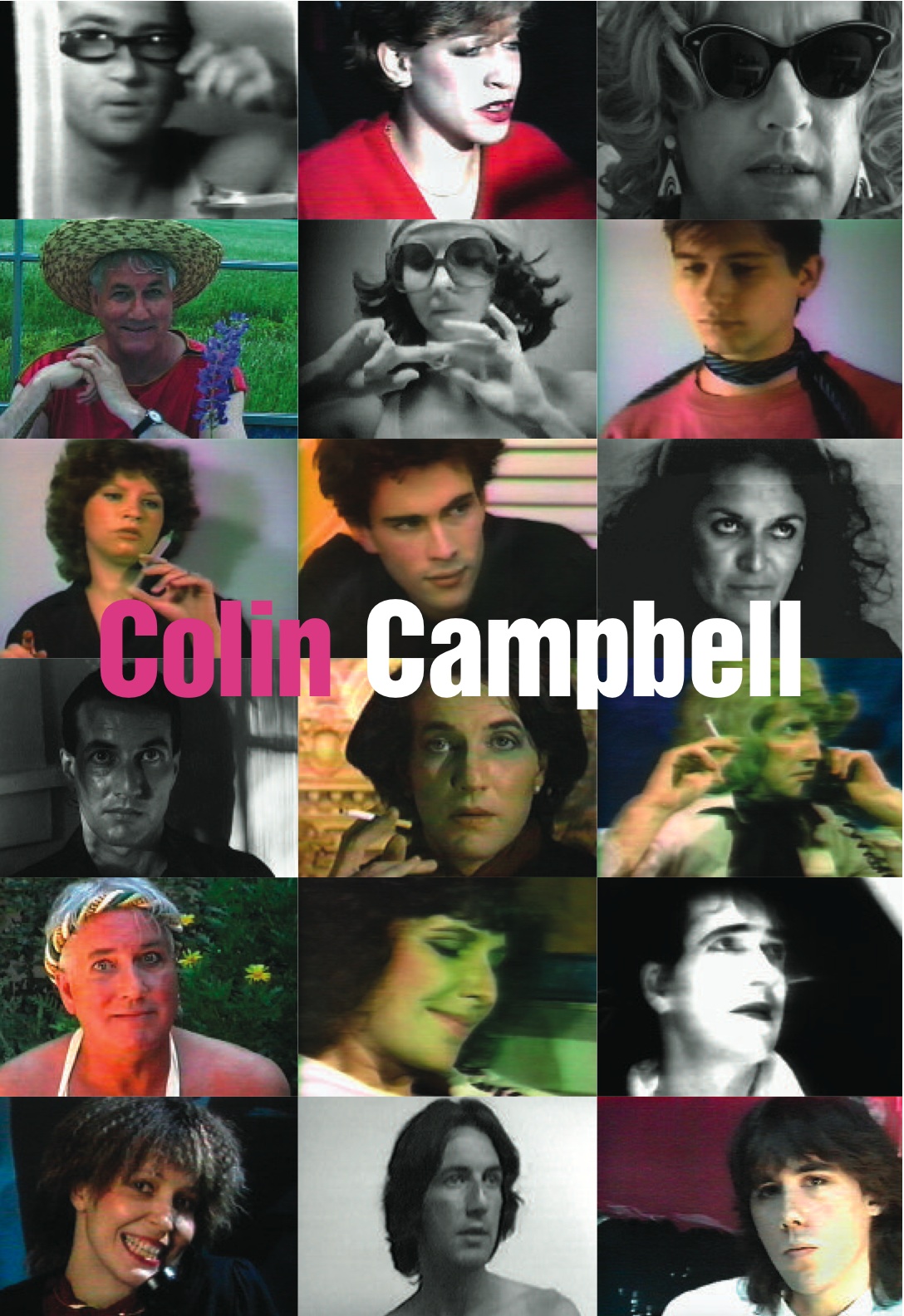

Colin Campbell (1942-2001)

Colin arrived one sunny afternoon on the phone. He was already dead, so the voice on the other end of the line wasn’t his. As usual, as he did so often in his work, he was throwing that smooth, measured voice, and allowing it to occupy someone else. Now it had turned into Lisa Steele, tireless co-founder (along with partner Kim) of Vtape, the artist’s video distribution joint here in Toronto. She was commissioning a series of new shorts responding to the work and life of video artist Colin Campbell. Was I interested?

I had met Colin exactly twice. Meeting was hello in a crowded restaurant (he was entertaining guests, I was passing through), our reprise a slightly longer exchange at an opening (was it?). He made the approach of course, throwing the charm spotlight on long enough to let some witty bonbon slip past. When I remarked on his killer tan he waved his hand between us and assured me it was bottled. I misunderstood immediately, imagining that his skin had arrived in a bottle, so I stood there gawping at him (my usual party demeanor) before he floated off on someone else’s breeze.

Can we speak of popular ideas or received notions, even here on the fringe? The usual uptake is that Colin lifted today’s headlines and turned them into tomorrow’s witful monologue. His tapes are heady with celebrity mentions and drive-by shootings after all, censorship lampoons and AIDS protests, all signs of the times, right? And if those weren’t evidence enough that the news ticker’s heartbeat ran straight up the mainline of his work, there were even a pair of movies made at Toronto insider hotspots which not only celebrated clubhouse passions, but became part of their legend. Dishing the evidence in weekly installments before the knowing in the very same venue seemed icing on the avant cake. But as I felt along the seams for a way inside, I couldn’t help feeling that his present-tenseness was another mask, and that he was more properly understood as a citizen of the 1950s, with its scientific infatuations, its cold warrior atomic secrets, and the birth of television, which Colin replayed in his own, smaller-than-life, home-movie fashion.

Months later Lisa’s program The Colin Campbell Sessions passed in a haze of good intentions, reminding all of us that the eulogy machines of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs ensured only an accessibility of first world production. Did the stone masons tasked with graveyard epitaphs ever carve in error? Produce indifferent scripts on grey days of inattention? Each onscreen offering was given an emotional free ride because Colin had died only a year before, suddenly and tragically from colon cancer. Within a few months of diagnosis it was over, there was not even time to spend his last half year (which doctors warned him was all the time he had) to fill his new, beautiful, writing paper with letters to friends. Do you remember when? This is how he planned to spend his last months, penning farewells. Now that work would be left to strangers.

From Nelson Henrick’s True Lies or The importance of Being Colin: “Immediately after I learned of Colin Campbell’s death, I went shopping. October 31, 2001 was my last day in Canada before leaving for Argentina for ten days. My partner’s birthday would occur while I was away: I needed to buy him a birthday present before he came home from work that night. So there I was, walking to a bookstore, sobbing to myself. And I thought, ‘This is a very Colin Campbell moment.’ I could hear his deep and pause-inflected voice slowly saying, ‘After I heard about Colin’s death, I went shopping.’ And this made me laugh, and then it made me cry, because what Colin gave us is the ability to detect ‘Colin Campbell moments’: these times when the serious events of life become burdened by the spectre of the ridiculous.”

Cold war moments provide deep background and improbable genealogies for the new art of video: the Korean War forces the Paik family to seek shelter in Japan. A dozen years on their number one son is humping his way back from the Sony warehouse in New York with the first “portable” camcorder in a box on the seat beside him. When traffic stalls to allow Pope watchers a better look, there’s plenty of time to unwrap the new machine. When he showed the results later that night at Café a Go Go, video art had found its primal scene. Colin was one of the first to claim this inheritance, plugging in when “portable video” required serious muscles to haul gear around.

In the old days of video art, editing meant taking out a razorblade and sawing through a ribbon of tape, leaving an ugly scar in the middle of each frame. As a result, editing didn’t happen all that much. Sound was funneled live into a microphone nipple perched on the camera, ensuring maximum line hum and glorious mono. The image was grey and white and soft, so very soft. But this was the portable video camera that was going to lead the revolution, that was going to put “television” into the hands of “us,” and with our brave new pictures we were going to take down the Man, the establishment, the five corners of the Pentagon, the racist Pigs, the empire State, you name it. Big dreams for a low-fi medium. Colin played it closer to the chest, as usual, in his one-take, basement productions. He had trained as a sculptor, made some large inflatable abstracts down in Berkeley while the world was busy ending all around him, and then took the first job he could get, teaching art in the modest backwater of Sackville, New Brunswick. Their underachieving football team had enough bake sales to buy a video camera so the coach could figure out what was going so terribly wrong, and Colin was able to borrow it in the off-season for his charming, no-frills production. Sackville, I’m Yours (1972) was Colin’s first tape, and a touchstone for much that was to follow, both for his own prolific musings, and everyone else’s. He played the first of his many personas, “Art Star,” a legend in his own mind, in the midst of (sigh) yet another media interview. When will those reporters ever stop bothering him?

Give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth said Wilde Oscar once, in a moment before the law fit him with a mask which changed the face beneath it. Colin was never short of masks, which he recycled to great effect in serial, star-driven turns which saw him deepen the divide between acting and performing. He liked to begin each day by re-arranging his furniture, a tic he shared with his older sister, though they didn’t discover this about one another until late in their lives. When he was a teenager growing tall in small town Reston, Manitoba he would invite a few chosen handsomes, his and hers, to sip Cokes with the drapes drawn and coloured bulbs creating ambience. His furniture kept turning into sets, friends became performers, last night’s whispered confidence arrived as today’s script.

His Cold War rearing was marked first of all by the nuclear arms race, never before did the possibility exist that everyone everywhere could be destroyed. Perhaps it comes as little surprise that despite the tone of gentle humour and low-key camp that pervades his work, death is everywhere. It occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, from anonymous drivers and jealous co-workers, accidental plotters and strangers. Colin unleashes his torrent of endings so amiably it’s sometimes hard to remember, by the end of the tape, that anyone has passed away at all. As Steve Reinke once remarked, Colin is at his most humorous when he’s talking about death.

On-camera, Colin preferred a mask of see-through drag, where he could open himself to the slings of outrageous misfortune as s/he lost her manager, band, husband or daughter, all the while stalked by lechers and killers. Part of Colin’s teaching and trace, the way he has marked me, is his great gift for lightness. How else to bear up, to weigh in, to hold forth — on these weighty matters, this impossible life, the one I held dying in my arms — except by making him so very light? Then, at last, it would be possible to say even the most difficult, the most impossible thing of all. Good-bye.

In her seminal essay “Notes on Camp” (1964), Sontag writes that the camp character refuses depth or development, from the first appearance to the last there is no further insight to be gained, no hidden trauma at last revealed. Is it too much to say that the camp persona is an atomic character, that s/he appears all at once, in an instant, a flash? Colin’s beguiling personas, whether Art Star, or the three sisters: Mildred (aka The Woman from Malibu), Robin (the suburban innocent who achieves a moment of underground musical success), and Colleena, (a breathless, performance artist) all deliver their personalities at first glance. While they are occasionally carried up in storied inventions, their fundamental character never bends or changes, they don’t show us more by appearing more often. The camp masks that Colin reaches for are atomic characters who appear in an instant, a flash, like the atomic bomb itself.

The picture of the atomic bomb most of us carry is the issue of careful grooming and manufacture. It is not Little Boy or Fat Man but Able, the bomb which exploded off the Bikini Atoll in July 1946. It was the largest media event ever convened, and provided spectacle fodder for the fledgling medium of television. Because of the required distance from the blast, the pictures produced were abstract, even picturesque, and so very clean and tidy. Like most of the pictures which surround us, they were not made in order to show, but to conceal. What is missing from these pictures? This camouflage? The bodies of those burned and disappeared in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And it is exactly the body which returns when artists take up their own video cameras, refusing the televised spectacle of state camouflage, and returning to the collective repressed trauma of destroying the citizens of two Japanese cities.

Colin is not alone in performing this act of grieving for those never met. And neither is he unusual in using the means at his disposal, a local happening, a beautiful face from last night’s gig, a visiting performance artist, a friend who needs a little pick-me-up. Hey, what are you doing this weekend? Do you want to come over? I’m going to rearrange the furniture and make a video. Again and again these lighter-than-air scenes move towards a terminal point. And if he permits his masks to speak more than occasionally from beyond the grave, it is because it is the voices of those burned up in an instant, vanished at what they used to call Ground Zero, who are speaking through them. The mask of lightness arrives to carry whatever is impossible to bear. Just as the mask of the local appears to disguise the faraway truths, the deep wounds of empire.

Harold Edgerton was the inventor of the flash of flash photography, and then those too beautiful pictures so many of us have in our minds, of slow-motion liquid drops falling onto surfaces and exploding with a once-invisible grace. His work with flash photography was instrumental in the development of the atomic bomb, it became part of the triggering mechanism, part of the puzzle which had kept scientists locked out of the atomic world. How strange that his ultra-slow-motion movies of milk drops so closely resemble the atomic blasts that his invention made possible. And that Colin himself appears as a flash photographer in Disheveled Destiny (2000).

As I rolled through the hours of tape he left behind, I became haunted by an image which appears at the end of his Women from Malibu sixpack which featured Colin as a blond-wigged, sunglassed incarnation who spoke one. Word. At. A. Time. Colin’s drag persona appears as a stunned witness of catastrophe in the afterburn of the bomb. She wanders the empty ruins of the image empire, appearing always in small, closed rooms, talking like she has all the time in the world, with a toaster on every table and a steady drip of slow-motion stories which always seem to wind up in death. At the end of this six-part series, she wanders into the desert, ostensibly in search of the pony skeletons her dead husband collected, which lay scattered still about her basement. It is a nearly unique moment in Colin’s early work, because here the camera is out of doors, and instead of the steady run of talking close-ups, there is no talking here at all. In the face of her inevitable death, which she has decided to walk not run towards, there is nothing left to say. The wind blows, she pauses, and then she strolls away from the camera, and from us, a figure growing ever smaller. This is the first time we see all of Colin, the blonde wig tussled ever so slightly in the wind, the high heels stepping gingerly across the desert. When I saw it for the first time I thought: oh, he’s coming home. Or simply: home.

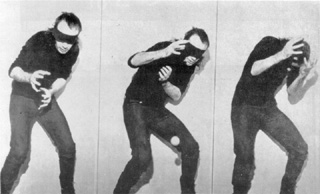

The atomic characters of camp, the flash photographer, the atomic desert. These are the three figures which underlie so much of Colin’s work. And of course there is the splitting of the atom itself which produces the bomb, and this is a split which Colin replays in his incessant gender bending, or in a movie like True/False (1972) in which he offers a list of personal declarations (I snort coke. I collect pornography. I recently attempted suicide.) followed by the words: True. False. Which is it? Well, after the atomic blast, he offers us an image of fissure and rupture, of the two in one, again and again. The atomic body is also the queer body, folded over, bent, turned in multiple directions, at the same time.

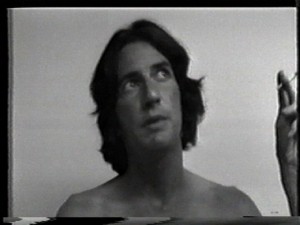

The division of the atom, the two selves, the image and moi. In Real Split (1972) a photographic close-up of his face occupies one half the screen, while his face occupies the other. In Janus (1973) Colin makes another early stab at non-narrative reflexivity (mercifully abandoned after this effort) with an 18 minute fondle of a life-size photograph of his naked self. He is also naked, I think it was a rule then, no standing in front of the video camera without your clothes on. And a way of saying: this body is a picture. Like the people vaporized by the bomb, turned into shadows.

In 1974 he moved south into a New York loft, and inspired by its architecture, he recast it into narrative, playing all the parts himself. The atomic divide continues here as well. In I’m a Voyeur (1974) he spies on himself, in Hindsight (1975) he produces a figure against the ground of other’s stories, while in Secrets (1974) he unveils a small proscenium space with curtains opening and closing the action, offering a confessional portal and the staging of subjectivity.

In the more fully realized dramatic scenarios which followed, he cast his internal division out amongst friends and familiars, allowing others to take their turn as ventriloquist foils or costumed reversions of themselves. He invited them to don a mask and embrace their atomized, divided personalities, projected outwards and available for even casual viewers, at a glance, in an atomic instant, a flash.

After retiring from the hectic video world and the endless catering which his increasingly sophisticated long forms required, he wrote a pair of novels, both unpublished, and then began his “second period” of video making. Here he reprised his earlier characters, and set them into dialogue with previous incarnations, excerpting moments from earlier tapes and having prior versions of himself chat with a much older, but no less dapper-in-drag Colin. In these tapes he is multiplied (playing different parts, confronting himselves in the present, and again in the past). Alongside his familiar embrace/division of man and woman, he adds the divide between then and now. I am and I was, both together now, in conversation.

If there is a stunned witness quality to so many of Colin’s portrayals, a devastated attention to the details of a moment in the car, or lunch for a daughter who never comes home, it is because these details arrive to fill in the gap, to take the place of what is not there, to perform the work of mourning. His campy melodramas, his non-passing drag, his sometimes excruciating decisions to cast friends in roles where we watch them attempt to dish his smooth lines through a haze of awkward self-awareness, all this is testament to the difficulty and necessity of mourning. And if he kept it all so very, very light, it is because his atomic secrets were so very dark. Like what, for instance?

After the second world war there was a dramatic growth in American foreign business activities, accompanied, as usual, by expansions of the empire. There are too many examples to include, but this one was pivotal. In 1953 Iranian Prime Minister Mossadegh was overthrown and killed in a joint U.S. (CIA) and British operation after announcing plans to nationalize the British-owned oil monopoly. The coup restored the Shah to absolute power and began a period of 25 years of repression and torture, with the oil industry being restored to foreign ownership: Britain and the U.S. received 40%, other nations 20%.

The Nevada Proving Grounds, just 100 kilometres from Las Vegas, hosted more than 900 nuclear tests, including 100 above ground. Tourists came to Las Vegas so they could watch the mushroom clouds from their hotels. It was sold as spectacle and a marvel of modern science; the fact that the government was systematically poisoning and killing its own citizens didn’t come out until much later. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990 has paid out to more than 10,000 Americans who were injured or killed because of these nuclear tests.

The role of television was to provide the rationale for an increasingly open and interventionist foreign policy. The result was an explosion of documentary programming, particularly in the 1960s, and an increasing emphasis on underlining the Communist “threat.” Little surprise that many of the producers and correspondents began their work during the second world war. Television became war under another name.

The cold war and the cool medium. In contrast to globalized broadcast and the reach of empire, artist’s work offered local, resistant strains of non-commercialized image production. And in place of the globalized broadcast village, Colin set to work creating a community, going out night after night, drinking and dancing and attaching himself to art bands and nights that never quite ended. And some of these scenes were laid out in front of the video camera, masked and masqueraded and plumped in front of the glassy stare and asked to talk. It all seems so local, particularly now when these once glam denizens are getting on themselves, or have already joined Colin in that other placeless place. But even in the many years when his perfect skin must have assured him each morning that he would live forever, Colin was haunted by the dark truths of empire, by the corpses which lay beneath all that clean science, by the militarized technologies that ensured a steady upgrade of portable equipment. In his very private reaction shot to the harsh dichotomies of the cold war, Colin’s life was lived in stereo. He demonstrated this important truth: that it was possible, even necessary, to live two thoughts at the same time. Not either/or but yes and yes.

The movie I am trying to make about all this is called Fascination, and it’s framed by pictures of the (nuclear) desert, an iconic location in the western imagination, whose primal scene might rest somewhere in the pages of Exodus where the tribes of Israel are cast out of Egypt and forced to wander the desert. The desert is not a place of stories and destinations and arrivals. Instead, it is a site of wandering and trial, and if this story still speaks to us today, perhaps it is because each of us has also experienced a desert in our own life, a moment when the old truths no longer hold, when we no longer know how to talk or touch. The desert is a picture of a person, the subject of this biography, this Colin Campbell, but it is also a picture of a movie which proceeds by wandering, which delights in being lost, taking up tangents, following leads and losing them.

For now my work on this post-biography continues. It takes a long time to say yes. Longer even when the yes belongs to someone else.

Colin Campbell interview by Peggy Gale (1982)

(Originally published in: Parachute September/October/November 1982)

Peggy Gale: I’ve noticed a trend in the last year in video. I’ve seen six or seven tapes in the last month that have not been talking heads, people delivering lines. Like the tapes from New York at Gallery Quan, nobody said a word. It was all music and overlay. And at Art Metropole — Les Levine, Paul Wong, General Idea — it’s all images with voice-over. It seems like a split is already going on, where content is on one half of what’s being produced and visual assault is really on the other side. It plays to the thirty-second attention span that everybody has about everything. It feeds that. It’s a sort of a renaissance of the technology of video all over again. Only this time, what is accessible to artists closely approximates what’s possible to do in a commercial television studio. Do you think that consumerism per se is one of the contents? It’s certainly become part of the form. It’s attractive, seductive… but I wonder whether the artists are actually commenting on that or just welcoming it?

Colin: I think it’s a bit of both. The progress of video outside the art ghetto has been amazingly slow. The majority of work produced is shown in an art context. Pay TV is here, broadcast TV, cable TV, whatever. Video has moved into nightclubs and rock clubs, but the kind of work that has moved the most successfully in that direction has been image-conscious video as opposed to narrative. Video also has a history of being a tool that multi-media artists use, go in and out of, so there are people who do performance and write books and do the occasional tape… It seems that kind of work is being picked up on. It’s like the renaissance of video imagery again, now in its new highly technical stage. It’s glamorous again. The images are fabulously glamorous again, seductive and rich and varied. What I see about a lot of that work is that it still does convey a sense of awe. You don’t see anyone pulling the strings, all you see is the results.

Peggy: Do you think it’s a return of the literate?

Colin: Certainly the last two scripts I’ve written have demanded much sharper attention than my previous work has, and refer more to things outside the art context than my previous work. But that’s the demand I made on it to keep it interesting for me.

Peggy: Earlier you were talking about seductive images, and that so many tapes are non-verbal but very heavily loaded with content. Yet we’re also saying that their very strength lies in a narrative structure at the bottom. To me, the new work that is really successful is using both. Given that colour is pervasive now, you have to have both those elements. When people first began to use colour, I think almost everybody was dismayed to find that although the work was prettier, it looked stupid, whereas black and white could be extremely extended in time, but it never looked stupid. What I’m searching for, is to somehow isolate this seductive presence physically, the use of color, the new approach to time and structure, and the narrative underpinning that gives it substance. When you have all of those together, as I think Dangling By Their Mouths does, for example, you have another order of videotapes that is far more than television, and more than film too. It really is a different form that doesn’t exist elsewhere.

Colin: I’ve always found colour in video or television unnatural. It’s electronic, and none of those colours are real anyway, and then there’s the inherent flatness of the video image. You don’t get that richness of depth any more in colour than you do in black and white. In fact, it seems even flatter in colour somehow. So when I approached Dangling I wanted to say, “This is a colour tape,” as opposed to, “This is not a black and white tape.” So I used slide backdrops for almost the whole tape, as a narrative structure, but also to try to get a diffuse kind of light that was somehow richer than on-scene location shooting could ever be. I also used large black and white photo backdrops in the tape in a couple of places, again as a narrative device, and also to say, “This is an approximation of reality.” In Conundrum Clinique I used either strictly flat, bright, grid colours for the background, or slides again.

Peggy: It seemed that you came to colour at a time when everybody was working with colour. So there was a sense of inevitability about it. It wasn’t as if you had struck out on your own. There had been people working with colour for three or four years already, but those people were working with colour as an ideological decision at base, whereas by the time you decided to move into colour it was because of something quite different. The same shift seemed to happen for a lot of people….

Colin: I started to appreciate colour in film when I saw Antonioni’s Red Desert, which was his first colour film. It was mostly shot in industrial settings, grey, white and red dust. At points there were real moments of colour and when there was colour introduced then it seemed to parallel a heightened sensitivity or awareness of the characters involved in the film. In the first colour tapes I saw, on the other hand, I was very unmoved by the fact that they were in colour. I thought it certainly was something for a black and white tape to come up against, but I’d seen hundreds of colour films before Antonioni’s and that was the first time I saw colour could be a vehicle as much as a fact. I was in the process of making Bad Girls when I switched into colour, mostly because of accessibility to the equipment. But when Bad Girls switches into colour, nothing much is enhanced.

Peggy: Yes, it not like Dorothy arriving in Oz.

Colin: Right. So I started to think about how to use colour. Sets in video don’t look like they’re supposed to look, which is why in He’s a Growing Boy, She’s Turning Fourty, which is my first full colour tape, I use mostly black and white sets and blow-ups, because I want to reduce the colour to where it really mattered. I did try to keep the tape mostly in black and white and accentuate some developments in colour, particularly the last shot, which is very loaded with colour. The camera is set askew. So it’s more magenta. That was the first tape where I tried to manipulate colour consciously. And with Dangling I wanted to make it as lush as possible, feeling that colour can do that, that it’s a real element to work with.

Peggy: Do you think my dissatisfaction with other people’s transitional tapes is that they haven’t realized that they’re transitional? They haven’t taken responsibility for the colour, but are simply using…

Colin: I think that’s really possible. Why just accept colour as a fact, because it is an emotive force and why not try to use it as one? It can be specifically directed, consciously, as opposed to unconsciously.

Peggy: But what about the other issue which is implied by colour, its commercial reference? It seemed to me that the reason you didn’t move into colour earlier, when you could have, was that you were interested in the elegance and intimacy of the black and white, and the kind of classic look of it. Classic photographs are in black and white and classic television is in black and white. You specifically were not interested in the commercial relationship to be brought to anyone’s attention. Now with your move to colour, you’re using colour for its emotive appeal. And are you still just ignoring the reference to television?

Colin: No, of course not. A good example is when I showed tapes recently at the Art Gallery of Hamilton. The first tape I showed was black and white, The Woman from Malibu, and when I was ready to show the next one, people asked, “Oh, is it in black and white too? Oh good.” There’s an expectation for colour now, and I think it’s hard to get away with shooting a black and white tape. You feel the same in movies these days…

Peggy: That’s not really the question I asked, because what you’re talking about is audience appeal, about audiences that are not looking very well. They’re simply sitting and waiting to be pleased. On that level colour has made the work more accessible, so colour can be a ploy to reach people who wouldn’t otherwise be bothered. Which is certainly good politics, because everybody’s talking about enjoyment. Everybody’s a consumer, and we’re a long way from conceptual art. But what I was really asking was another sort of issue, which is, is commercial television being addressed directly or indirectly by the kind of work you’re doing now? It seems to me you’re moving towards the possibility of the work not being seen as capital A art, but being seen as very unusual television.

Colin: I think that’s true. I guess what some video is doing right now is borrowing the best of the sensibilities of film and television, but there’s still a grittiness about video that talks about television. It’s not as seductive as film, not as palatable.

Peggy: Do you think that either consciously or unconsciously you’ve been working towards the possibility of broadcast with these recent works?

Colin: I can’t say. For about three years, at least, I’ve had an interest in reaching an audience outside the specific art gallery audience, which never seems to grow very much. That’s why I chose to make and show Bad Girls in a bar (the Cabana Room, Toronto). So what if they’re there for the band, they’re still there for the tape, too, whether they want it or not. I really felt that I expanded my audience and got very different kinds of reactions to what video was, from that audience. The response was both good and really bad, everything from beer bottles at the screen to people shouting “turn it off,” to standing-room-only and everyone saying, “Sshhh, there’s a tape on.” There were a lot of musicians there who generally never went to galleries to see tapes, who liked the motion of the tape. I tried to keep it short, and, you know, Perils of Pauline. In general, nobody said they were bored… For a long time artists said, “No, video isn’t television, it’s video,” and I think people are reconsidering that. I certainly am. I’ve always viewed broadcast television as not undesirable but impenetrable, and I’ve also seen we wouldn’t be given the chance to work creatively in a studio situation. I think that a lot of videotape being produced now cannot be just popped onto broadcast television and sit there very comfortably. But I think, yes, given the chance to do a production for broadcast television, my work would change, my ideas would necessarily alter in that process, and I’d love to have the chance to do it. So obviously I think something good could come of it.

Peggy: I wonder how the issues to be addressed will change as it becomes possible to access that audience? In Toronto, the narrative work is different now. I think there’s something different happening.

Colin: I think so too. For one thing, it’s a much broader cultural collage that’s being contained within the work. A lot of earlier video talked about the system of art and was quite formalistic. Even within narrative I think it kept addressing art issues, whereas now the work is much more out in the realm of common experience. Characters are identifiable now as real people.

Peggy: We are assuming that video will not become television but will continue to be something evidently different and acknowledged to be different. If you’re no longer going to be simply closed-circuit, what are the properties that you will try to bring out in your work?

Colin: The idea of intimacy hasn’t been explored in television. It would have to be altered in the way it would be done, but it could be very startling once it started to work, to be used in work that’s being broadcasted, not as video art, but as broadcast television. I think much more complex ways of getting a narrative across could be used, rather than the particularly linear way that most television works right now. I would assume that there’s a large number of people out there who can withstand a more complex layering of ideas… Watching television like the Olivia Newton-John special, I think that if an audience can be whisked around visually that fast in four minutes, then think if it had some content in it! Artists’ initial response to broadcast television has been, “Oh, great, we can put our work on and convert the unconverted.” Not true. Or they’ve thought, “Okay, well to be on broadcast television you have to sell out and become like television.” I think that’s not true either. Television doesn’t need that, it has enough people doing that already.

Peggy: After Dangling and Conundrum Clinique, how would you see the next step if you were moving towards broadcast as your next possibility?

Colin: What I’m specifically interested in doing right now is almost completely non-linear kinds of pieces, quite short, from ten to fifteen minutes. Maybe even five minutes. I’d like to produce work that’s about the thought process of producing it. Wouldn’t that possibly have an equal although different kind of impact than one which is all tidied up and strung out to be completely comprehensible? Our perception of the world is not a tidy linear process, and I want to investigate that. My idea of the next tape is hat it may be ten minutes long with six different characters who don’t relate to each other in any way. Seeing what happens.

Peggy: Do you see other people looking at similar notions?

Colin: In Rodney Werden’s Yes (36 minutes 1981) there’s that dissociative and discontinuous… there’s a huge cast in that tape that seems to have nothing to do with each other at all. It’s bound by the thread of an underlying narrative. I think that’s a real transition point for Rodney’s work, it’s s much more complex narrative style than we’ve been used o. He’s the first example that springs to mind.

Peggy: But you’re not conscious of being part of a trend?

Colin: No. But I don’t think you ever are, then suddenly four people come out with tapes simultaneously with new ideas that are closely related.

Peggy: Nevertheless, to know that there’s a not a conscious sharing of these issues is significant because it means that everyone’s going ahead by guess and by golly.

Colin: I agree with you that there’s some kind of turning point happening in video right now. Just at the point that video may be approaching an extremely broad sort of audience, it’s also becoming much more sophisticated and complex and demanding in another kind of way… But in just the last three months, people have been coming from Pay-TV down to Charles Street Video, and looking at tapes. “Never seen anything like this before, I really like it, don’t know what we can do with it.” Even that is such an unexpected response. They’re responding. So of course it’s going to influence people’s thinking.

Colin Campbell Interviewed by Kathleen Maitland-Carter and Bruce LaBruce (1987)

(Originally published in CineAction! Summer 1987 No. 9)

Kathleen Maitland-Carter: I thought we’d begin by finding out about your background. I know that you paint, but I’m not sure if you painted first and then got into video.

Colin: I was a sculptor for ten years and then started making video tape in 1972. What kind of information do you want?

Kathleen: Your early tapes such as Janus are more sculptural.

Colin: At the time I started doing video, it had just started to be used, primarily by sculptors, and it was used in its original format as an extension of body art and installation, so a lot of sculptors did start to use video, and then most of them didn’t stay with the medium, most went on to conceptual art and that kind of thing. But I stayed. So my early piece are quite sculptural, very formal.

Kathleen: How did the transformation come about, from doing more sculptural work to incorporating narrative?

Colin: The first five or six pieces are very formal, and then I did a tape, while I was teaching art at Mount Allison in New Brunswick, which was where I started doing video, called Art Star. And it was basically a rant about how awful Mount Allison was and what it was like to live in Sackville. So that was the first sort of narrative piece I did. That was the first time I spoke. And that was also the first tape I ever exhibited. So from there up until 1977 I did work that was mostly autobiographical, or focused on how I was interacting with the world. Then in 1977 I went to California and did the Woman from Malibu series, and that was the first really scripted material I did where I impersonated another person altogether and turned the camera away from me completely and I started dealing with external fiction as opposed to internal fiction.

Bruce La Bruce: Your work obviously has a lot of affinities with film – not only the narrative stuff you do, but the appeal to melodrama and the signifiers of “women’s pictures.” There’s also a move away, in your work, from an art-based focus to something maybe broader, less esoteric…

Colin: Are you talking about the recent work?

Bruce: The progression from your other kind of formalist work to more accessible work with dramatic monologues and melodramatic elements. You could almost identify some of your video work as one long melodrama – the Women from Malibu series or the Modern Love series, looked at as a whole, are like one long movie.

Colin: Yeah.

Bruce: I just wanted to ask about that and also why you don’t work specifically in film, why you’ve chosen video?

Colin: OK, that’s two questions.

Bruce: Yeah. (giggle)

Colin: The Women from Malibu series is a total of 90 minutes, but I think it’s still more easily identified with an art practice as opposed to filmmaking, simply because its structure is too quirky to be viewed in terms of film practice. But the later work, the work I’ve done in the 1980s, is more filmic. I’m getting back to much longer pieces again, and as far as I’m concerned, the piece I’m just editing now could have been shot in film. It could be a film. It’s quite long, about 60 minutes. But why don’t I work in film? I can’t afford it. It’s really simple. I’m sure you know better than me the problems for independent filmmakers. So for practical reasons I continue to work in video.

Kathleen: Film is very expensive, but with independent filmmakers – feminist, lesbian and gay filmmakers, black and Asian filmmakers – they find their community, and there are international circuits set up through events like festivals. So there is a lot of interesting film work being done. I think the difference with video is that the advent of video technology – porta-packs and so on – make it much more available to artists and cultural workers when it came about in the late sixties-early seventies, so it seems to have developed a stronger, more cohesive community. And because video is so recent, there’s a lot of women working in it as well, that’s why it has a strong feminist tradition. Whereas film has a kind of troubled history, especially ‘avant-garde’ cinema because it’s come out of a more formalist, masculinist tradition.

Bruce: Well, the whole ‘industry’ stigma around film, in which the more careerist, aggressive ones make it, seems to be more geared to a masculine discourse.

Colin: Yeah, I would agree.

Kathleen: Which is something that your video work undercuts. I wanted to relate all this to your work with drag. It seems a lot of portrayals of women by male transvestites are really misogynist. I think your work escapes that.

Colin: Uh-huh.

Kathleen: Have you ever been accused of…

Colin: Misogyny? No. Well, let me see, the first time I did drag was in The Women from Malibu. I was actually going to try and find someone to play the part and then I decided I could probably do the material best if I did it myself, so I went to the Salvation Army and I bought the wig and the clothes and jewellery and everything…

Bruce: Was that traumatic? (laughter)

Colin: No, not really. They probably thought I was going to rob a bank. Anyway, I dressed up and did her, and I thought it was just going to be the first ten minute piece, but it turned out, for me, she was a really good vehicle to discuss the culture of Southern California.

Bruce This is when you were living…

Colin: Yeah, in L.A. So she sort of took over for the nine months I was there (mostly doing research and then shooting the tapes). I never tried to actually disguise the fact that it was me or that it was a man, like, I kept my same voice. I tried to keep her fairly neutral and not campy, actually, because it never occurred to me. I knew that might be an aspect of it, but it never seemed to enter the material itself. I premiered the work in Victoria and I was extraordinarily nervous because suddenly, it’s that kind of naivete, you make a couple of tapes, you think they’re fine, then you forget you’re going to have to show them and be there. Show and tell. So I was quite anxious about it, but the students were extremely positive and there just didn’t seem to be any question about it being misogynist. So I don’t think it is. I don’t think the Women from Malibu is misogynist, nor do I think Robin, nor Anna in Dangling By Their Mouths. But I mean the question has come. Do you think it’s misogynist?

Kathleen: No, I don’t think it is. I think why it escapes being camp and why it’s not misogynist are interlinked, you know, what Susan Sontag wrote about camp, that the characters are never developed in it, instead they’re more iconic or fetishized, whereas you characters are really developed.

Bruce: I think the fact that you do use a neutral, masculine voice really is part of that. It puts you in the position, when you’re watching it, where you almost have no gender affiliation.

Colin: Yeah, it’s also not really sexual. I mean, again, it’s neutral, but there is no sexual interplay generally. My concern with all that material is about gender anyway, and stereotypical roles, and trying to address that as being a serious problem. I’ve never felt comfortable in any specific role in terms of sexuality or gender that I’ve been exposed to, which is why my work addresses that all the time.

Bruce: In her “Video in Drag” article in Parallelogram, Dot Tuer says that “Colin Campbell chooses to construct the feminine by banishing the masculine.” She was referring to your tape No Voice Over. What do you think about that? Do you think that masculinity is irredeemable in your tapes?

Colin: No, although I think what Dot wrote about No Voice Over is very accurate in the sense that I was trying to set up a situation where the communication between women is quite extraordinary, a kind of communication that it is mistrusted by men because they experience it themselves. Especially straight men. I guess I was trying to illustrate that my observation of women being able to express themselves to each other is always critiqued and under attack by men, and in the tape Dix-10, who’s mostly the voice off camera, his only way of dealing with, say, Mocha’s premonition about Miranda’s possible death, is to think she’s gone crazy, or that she’s hysterical, and he, in fact, undermines their ability to communicate what is really going on. So at the end of the tape it is not quite clear whether they’ve got it back together or whether he actually has split their form of communication so that they stop paying attention and Miranda does get on the plane and gets killed. I guess it’s a somewhat veiled attack on white hetero-male dominance in society. I was trying to show an alternative that I find very strong and important and meaningful, which is the relationship between women.

Bruce: Like in Charlie’s Angels. Someone brought up that connection, where Dix-10 is like…

Kathleen: Charlie.

Colin: I didn’t think of that until after I saw the tape for the first time.

Bruce: I think Charlie’s Angels is pretty amazing, situated as it is in the seventies and the way that pop culture identified feminism…

Kathleen: Women with guns.

Bruce: Yeah! Did you like the show?

Colin: I’ve probably never watched it. I don’t watch TV so much. But I think the major difference between my tape and Charlie’s Angels is that my characters never really seem to be in the male’s employ. They only work for him if they need the money and I always have the sense that they can and do say no.

Kathleen: It seems there’s a transformation in the kinds of characters that you’ve developed, from the Women in Malibu character, a lower middle class, California kind of ladies’ auxiliary housewife, and Robin in Modern Love, who is a kind of suburban, also lower middle class xeroxer, to the women in your most recent tape, I mean the class different is really evident. Why did you choose to start using these kinds of characters?

Colin: Because I think they’re richer, there’s more to do with them. I mean, the thing about Robin is that she can’t improve, I can’t sent her to university, you know?

Kathleen: You sent her on CUSO.

Colin: That was a good scam while it lasted. But generally I can’t see her changing very much. That’s part of her charm, but in No Voice Over there’s much more to deal with, the characters are capable of consciously exploring issues as opposed to Robin, who stumbles into them.

Bruce: Mmm. Although there is the appeal of accessibility of the middle tapes, I mean, I can see them being played in a lot of venues besides art venues. I think it’s a shame they can’t be viewed more broadly, because they have that kind of appeal.

Colin: Bad Girls was made specifically for the Cabana Room (the bar in the Spadina Hotel) that was my idea of trying to break out of the art ghetto. It was shown every week. I shot a sequence and edited it and dubbed it and then showed it on the weekend, I think that went on for about seven weeks. It was great because it really was a different audience, it was sort of an art bar, but there was a lot of musicians and others as well. So my audience really changed at that point. It was an attempt to get out of the gallery situation for one night only — a precious one-night-stand thing — into a much looser environment that was more fun. It was also to try to get rid of the notion that video tape by artists was boring and dry and had no humour and couldn’t deal with anything except “high art.”

Kathleen: How self-consciously do you employ humour? Does it just seep in or is there a strategy?

Colin: It’s a strategy. It’s one way to make your characters sympathetic, especially if they can laugh at themselves. It’s also a good way to get some kind of information across that might be just too heavy it you did it straight.

Kathleen: It’s a tactic used by mainstream, dominant film and television, to employ humour to conceal its ideology, like Police Academy, for example, or Porky’s. It’s usually really misogynist…

Colin: Right.

Kathleen: And I find when you start criticizing that, people say, “Oh, don’t be such a stick in the mud, it’s just funny.” They dismiss it. In a sense, you’re kind of employing that strategy. (laughs)

Colin: The Porky’s strategy. (laughs)

Kathleen: It seems very revealing, talking about gender, anyway. It allows the character to be sympathetic where some people might have problems dealing with that concept otherwise, about men dressed as women, or identifying with women.

Bruce: But it doesn’t always work, like Kathleen was saying about camp earlier, which I think your tape Bennies From Heaven is guilty of. For me, it’s your least successful tape, and that’s partly because there isn’t the character development of the other tapes.

Colin: Yeah, that tape is a real throwaway. The only thing I would say about it is that it was a reaction against the preponderance and insistence upon high tech and high finish tapes that look like they should be on television. I guess I did it to remind myself, as much as anyone else, that you can be very loose with video and do whatever you want as sloppily as you want, that there’s still a place for that.

Kathleen: It seems there’s less room now for a kind of low tech or sloppiness – with all the younger video artists there’s this real insistence on “broadcast quality.” Your last tape also had higher production values than your previous ones.

Colin: Yeah, although nothing much really changed in terms of equipment or technology between No Voice Over and the ensuing work I produced. It’s all shot on VHS (1/2” tape) except for White Money and The Women Who Went Too Far, which had a better camera. But I really think it depends on the piece. No Voice Over had to be done that way or it wouldn’t work. But I know that some people nearly feint when they see a glitch or some drop-out on the tape. It’s like, I never see it, I don’t care.

Kathleen: It seems really unfortunate. It seems like almost a rejection of the history of video art, I mean, something about video that I find so appealing is its opposition to other kinds of media and television, which used to more evident in video production. It seems people are now going back to embracing narrative conventions.

Bruce: Well Colin, this interview is for the comedy issue of Cine-Action! So maybe you should tell some jokes or be funny.

Colin: Why did you choose me for the comedy issue?

Bruce: Well, the thing I like most about your tapes is that lot of the work is pure comedy coming from a comic tradition, like, from Jerry Lewis to Lothar Lambert, or whatever. I don’t know, just very broad farce or deadpan techniques which are classic and it seems to work very well in your tapes, whereas it seems very forced in other tapes I’ve seen, or comedy as a device that is very much signified as a device rather than being natural or spontaneous.

Colin: I think Robin was a perfect vehicle for comedy because in fact she never knew anything was funny, she never gets any of the jokes. She sees herself as dead serious and upwardly mobile and having a possible career in show business. What would happen, I thought, if you devised a character who took it all seriously? It would point out, in a funny way, what people were taking far too seriously. The same thing applies to Women from Malibu, although I don’t think that she’s a laugh riot or anything. She’s actually quite tragic, but there’s always that edge that she’s going to veer into something potentially very funny. Like when she almost runs over Liza Minelli, but she doesn’t know that that’s funny.

Bruce: Well, even when it’s not purely comedic, like the dramatic monologue that opens one of the Women from Malibu tapes about her husband being killed, I mean, that’s played straight, but it’s still funny.

Colin: Yeah, it’s very eccentric. That’s a verbatim quote from the L.A. Times – I remember reading it and thinking, “This is so weird.” I think she gave the interview when she was extremely traumatized from the event, but it seemed so strange that she knew that her husband fell 19,000 feet to a 31,000 foot level (laughter), a weird kind of detailing about a horrific story, and it was possible to use that kind of detailing to point out all the peculiarities of Southern Californian culture, where she takes it seriously but to the audience it seems really funny.

Kathleen: In Shango Botanico, when the same character is in the motor home with Lisa Steele’s character watching the Rose Bowl parade out the window and on television simultaneously, I thought that obviously functioned in the same way. I think there are problems with that one, though. In a certain sense it could be read as classist, just that we comfortably watch and laugh at them from a video viewing room or gallery.

Colin: Well, that’s the sort of oddball tape in the series. It doesn’t develop the way the other pieces do. It’s like a prolonged moment. But we did go to the Rose Bowl parade, that’s how we got the audio sound, and people actually do park their RVs facing the parade route. (laughter) They arrive three months before the parade because you have to if you want to get that good parking spot, and they look out their windows, sipping their coffee, and obviously watching it on TV to see what’s going to be coming next.

Bruce: I think that tape and the Robin tapes escape what maybe Lisa Steele’s The Gloria Tapes doesn’t. I like it on a certain level, but it seems to take a more condescending position toward that character.

Kathleen: Really? I didn’t find that at all.

Bruce: Well, that’s my feeling anyways, that she was critiquing something about the position of that character and how she was down-trodden by different male figures and so on, but at the time she was made into an intensely irritating character.

Kathleen: Really? I like her character.

Colin: I like Gloria, but those tapes of course are coming from a much different kind of situation, where Lisa, at that time and for a number of years, worked at Interval House, which is a home for battered women and children, so it was kind of natural, I think, that the continuous experience of her work – that was how she made her living – did spill out finally into her tapes. I think probably what you’re saying is one feels that Gloria always remains tragic and is never quite able to lift out of her situation, and the consequences are deeply wounding.

Bruce: Yeah, maybe that has something to do with it.

Colin: The consequences are ultimately much more serious,.

Bruce: Yes, whereas when you see Robin standing on the street corner with her umbrella waiting for a bus while the disco song “Fly, Robin Fly” plays on the soundtrack, it’s more tragic-comic.

Colin: Because Robin will probably never really be harmed, she’s always going to spring back. She’s curious, you know, but she’s finally not engaged in what’s going on around her. The consequences are never that deep – she just goes on to the next thing.

Bruce: Yeah, parties through life. (laughter) Now, I wanted to ask you some questions about personal experiences that might provide a background for your work, like, if you’ve ever had any experiences being attacked by people because of your sexuality? You know, queer-bashing. I don’t even know if you’re gay, specifically, but it’s almost not an issue, in terms of gender, for being attacked for those kinds of things.

Colin: I’m bisexual. It’s a peculiar position to occupy in one’s life because you get it from both sides. It’s certainly been the basis of a lot of my work – the gender blurring and the cross-dressing, the mix up and rejection of commitment to gender roles. Actually, there was one incident. I do remember once walking on the street with my son, who was about 13 at the time, and there were two gay men coming towards us, and as they passed, I heard one say, “Oh, he’s into chicken,” and I was really offended because it seemed that, regardless of which community one acts in, whether I pass as heterosexual or gay (as you know, there is no bisexual society, it’s just not acknowledged), regardless of which camp I’m in, I’m criticized by the other one automatically. Or in that case they assumed I was gay, and that I couldn’t possibly be a father, therefore my son must be some kid that I picked up. So that’s why I made He’s a Growing Boy/She’s Turning 40. I don’t know if you’ve seen that tape.

Kathleen and Bruce: Yeah.

Colin: … where I’m trying once again to deal with homophobia, and in some cases, homophobia within the homosexual community. I find much of the gay community extremely conservative, and it has interfered with my work, like my tape, White Money. I was trying to give representation to taboo images, things that we’re not allowed to see-like men fucking or women doing SM. I mean, you go to the movies all the time and you’re constantly watching heterosexuals making out, but until recently, you never see gay men, or you would see women having sex with each other but always from the male point of view. So I made that tape to challenge that fact, to give voice to a different kind of imagery. The tape was curated into a show in Ottawa, and a gallery worker insisted that the tape come out, and he was gay. He said that it was a shoddy way to represent sex between men and the tape was withdrawn because of that.

Bruce: Did you take him up on it?

Colin: Yes and no. I mean, I got my fee. I’m not sure what his position really was — he was really anxious about the fact of gay sex being on a tape in his gallery even though he was gay. The other thing was the censorship issue, I think he was afraid the police were going to come down on him.

Kathleen: Prior censorship.

Colin: Exactly. And my position on censorship is well known.

Bruce: Yes, from your tape Snip Snip. How did you feel about playing head censor Mary Brown? I think your drag is usually so sympathetic that you almost make Mary Brown sympathetic – which is a Herculean task. What kind of response did you get from that?

Colin: Well, that was fun to do. Again, it was almost like the Bennies tape, in a way.

Bruce: Oh, I think it’s much more successful.

Colin: Yeah? I haven’t seen it for a long time.

Bruce: It’s really funny.

Colin: Oh good. I forgot about that tape. Well, that’s a collaborative tape between myself and Rodney Werden.

Bruce: The very concept of putting Mary Brown in a position of drag just works automatically because it would be so horrifying to her.

Colin: The funny thing was when we made that tape and it was shown at the Festival of Festivals, most of the audience didn’t know who I was playing. They didn’t know what Mary Brown looked like. So I always thought the tape never worked.

Kathleen: I thought it was a great characterization.

Colin: I guess she became well known after that.

Bruce: Yeah, she was very high profile.

Colin: At that time she insisted that her photograph couldn’t be used in the newspapers because the press took such unflattering photographs of her. So she censored her image from the papers. They weren’t allowed to photograph her.

Bruce: She became a real star. (laughs) She knew what she was doing.

Kathleen: Then there’s a character based on John Bentley Mays played by a women (Marian Lewis) that works well too. It undercuts the sense that a matriarch wields power viciously because of her gender.

Bruce: Have you met with any other kinds of resistance from the gay community?

Colin: Not specifically, but I don’t find that the gay community actually comes out and actively supports any of the gay artists working in video.

Kathleen: Not even for John Greyson?

Colin: No, I mean, it’s more the politically conscious groups. A real frustration of John’s is that his work isn’t seen by the gay community at large. It’s really a drag because I can’t think of anybody who works harder for the gay community. His last couple of tapes have had very explicit sexual material in them, and it seems like that really makes the gay community nervous, that they don’t want that kind of trouble.

Bruce: Mmm-hmm.

Colin: I have to say that it’s not a blanket condemnation. Some members do support gay artists, but I don’t see it.

Notes.

1. Dot Tuer, “Video in Drag: Trans-sexing the Feminine,” Parallelogramme, Vol 12, No,3 Feb-March 1987, p. 24.

A Work in Progress: an Interview with Colin Campbell by Sue Ditta (1990)

“For the Greeks, the hidden life demanded invisible ink. They wrote an ordinary letter and in between the lines set out another letter, written in milk. The document looked innocent enough until one who knew better sprinkled coal—dust over it. What the letter had been no longer mattered; what mattered was the life flaring up undetected… till now.

I discovered that my own life was written invisibly, was squashed between the facts, was flying without me like the Twelve Dancing Princesses who shot from their window every night and returned home every morning with torn slippers and worn—out dresses and remembered nothing.”

Jeanette Winterson, Sexing the Cherry

(Lester & Orpen Dennys Ltd., Toronto, Canada), 1990.

Curators often carry iconographic images of artists in their heads. My image of Colin Campbell has nothing to do with video. I always see him sitting in profile, hands hovering over the keys of a typewriter. Colin Campbell was in Ottawa in the fall of 1988 to give a lecture at SAW Gallery as part of the artists and their work series, “WHAT’S MY LINE.” Colin didn’t give a lecture. He did a performance, a performance that was built around “letters” he had received recently, including one from an art critic who wrote with witty, revealing and sometimes wicked insight about Campbell’s work and particularly, his writing. The letters were, of course, written by Campbell; the critic—a figment of his imagination.

That night I realized that Campbell was the only video artist I knew whose “lines” stayed in my head as long and as clearly as their images did. When I conjure up The Woman from Malibu in my mind, I see her/his face, her voice and remember almost exactly what she says. Postscripts from the letters in No Voice Over linger and the opening “voice—over” in Skin repeats itself to me, like a poem, over and over again.

There is a commonly held wisdom that the script, that writing in general, is not as central to the practice of video art as it is to film. This has changed in recent years as more and more video artists explore narrative. Campbell, however, has consistently distinguished himself as a writer and a number of his scripts have been “published” as part of the installation of this exhibition. Some of the scripts read like prose, whole short stories, tucked like hidden treasures within larger narratives. Others were very poetic, lyrical, constantly playing with rhythm and timing. I spoke to Colin Campbell in Ottawa, in October 1990. I wanted to find out when and why he started to write, how the scriptwriting process influenced his tapes and how the writing itself had changed as Campbell’s work developed from the very personal videotapes of the 1970s to the socially engaged, more complex narratives of the 1980s. I was curious too, about why and how he moved from monologue to dialogue, from the introduction of simple narratives to the ruptured, deconstructed narratives of the later period. This is a transcript of that discussion.

Sue: Colin, I read in an article that you hate interviews; that you don’t like doing them because they make you feel like a ping pong ball.

Colin: In most cases the interviewer doesn’t know me and consequently has me saying things I didn’t say or I’m misquoted. The other thing is my obliging way of answering any question, even if I don’t know what it means. Like… “Would I like to have acupuncture?” “Well, I guess I would.” So, quite often I’m too responsive and sometimes I get nervous and start making things up.

Sue: You feel you have to answer seriously even if the question is ridiculous?

Colin: Yes, even if it’s not relevant.

Sue: So, other people’s fantasies and fiction can come into play and then you yourself do some fictionalizing. There’s also a pretence in the interview format that suggests that somehow it’s more documentary, it’s more real than any other kind of critical piece.

Colin: Yes, because an interview, unless it’s on radio or television, has to be transcribed and someone else’s hand then comes into it. They have a way of making their questions sound better which may make your answer sound even more irrelevant. An interview masquerades as a conversation and really it’s not.

Sue: You explored the importance of writing in your work in a presentation you gave for SAW Gallery’s “What’s My Line?” series. You used your own mail and read something you had received from a notorious, fictitious art critic. Why did you use that format?

Colin: For one thing I used it because I don’t think I’m interesting enough to just talk about myself and why I do things. It’s very hard to make that interesting because the process of making a work is, in fact, very lonely and boring. I felt that if people were there as an audience, they wanted to be entertained in some way. Creating a fictional situation for them to play off or for you to play off them, slightly subverts their expectations of ‘Another dull evening with an artist talking about himself.’ If I told people the sources, the reasons, and the genesis of all my work, it would seem extraordinarily ordinary. So, by using a performance, I thought it might make my work more interesting.

Sue: You told us your story through the voice of an art critic.

Colin: Yes. A fictional art critic who in fact didn’t like me—who wrote about me critically, wrote about my techniques, my devices of fiction in a very critical way. But as I remember the piece—the critic eventually revealed that he wished he could be more like the characters I had created rather than being so critical of them. So, I used him to get across my points of view. It seemed a faster and more entertaining way to do it.

Sue: Could that piece be published or was it strictly a performance?

Colin: Actually it was going to be a three—monitor installation piece but it didn’t have enough merit. It was never intended to be a performance piece although the lecture at SAW Gallery turned out to be a performance piece in the sense that I started off the lecture by bringing all my mail to Ottawa and reading it out on the chance that there might be something racy or raucous in it. Of course that was all constructed. I had stuffed all the envelopes at home and the whole thing was a fiction.

Sue: I wanted to ask you about the development of writing in your life. We’ve talked about our earliest remembrances of artistic practice and yours in fact wasn’t playing with the camera or drawing or taking photographs. It was writing.

Colin: I think I went through puberty with a pencil in hand, in my bedroom writing stories and putting together fake magazines. I returned to writing almost twenty five years later and it’s become the most important thing to me again. In the meantime I had gone to art school and become a visual artist and sculptor. I abandoned that fairly quickly in favour of video. If I took the time it would probably be quite satisfying for me to make images on paper and I teach it all the time so, it is still a part of me.

Sue: Have you ever taught writing?

Colin: Yes. At The Ontario College of Art for four years. I taught script writing for film and performance and video and of all the teaching I’ve ever done, that’s what I loved most.

Sue: When you were young did anyone else read what you wrote?

Colin: No. That’s probably due to the fact that I lived in an extremely rural situation. I guess I could have sent things off to magazines but I always knew those were suspect, even in my utter naiveté, living in Reston, Manitoba.

Sue: It was a private practice.

Colin: Yes, it was. I don’t know if my friends knew I wrote; I can’t remember if I ever showed them anything. I don’t think so. But it was a very satisfying process for me.

Sue: You said you wrote fiction. What kind of fiction was it?

Colin: It was never short stories. I’ve never enjoyed the short story form because it’s too short. I think it was a sort of science fiction; space, other people on other planets, not so much about monsters as somehow messed up with a kind of religious thing. I really wanted to be religious and believe in God but never actually did. I didn’t write plays because I had never seen a play and to this day I don’t like poetry and I don’t think I’ve ever written any.

Sue: Did the writing have an autobiographical element?

Colin: I don’t think so. Where I grew up there were no artists of any kind—no dancers, no writers, no singers, (well, I guess people sang in the choir) but I read a lot. Although I couldn’t actually articulate it, I knew I wanted to be an artist and a writer. I never would have used those words, though. Writing seemed to me the most liberating, exciting kind of thing to do so I started writing. It was something I knew I could do. In my environment everything that everyone else was doing, I couldn’t do very well, like be a farmer or play hockey or be a pharmacist.

Sue: Weren’t you a bank clerk for awhile?

Colin: I decided to become a medical doctor and I went in and destroyed my parents’ and my own expectations of myself and failed practically everything so I became a recluse by working as a bank teller. I tried to figure out what to do and then I went and took a personality test in Winnipeg that said “What to do with your life?” They said do two things—be a doctor. I said I’ve already tried that. Then they said—be an artist. I said, how do I do that? And they said—you go to art school, and there’s one here in Winnipeg and you should go talk to them. So I did. And that’s how I came to be an artist. If they had said be a lace maker I’d probably be in Belgium right now.

Sue: You mentioned when you were young, that you really enjoyed writing. Does writing still make you happy?

Colin: Of all the things I do now, I would say that writing is the thing that makes me happiest—when it’s achieved. Not the process of writing itself—that doesn’t become any easier. But it’s the most rewarding thing when something is finally achieved and the writing that’s directed towards some other medium, like videotape or film I find the most satisfying. You can’t get a film or a videotape without good

writing so if I know the writing’s solid, then I know that I can probably get a good film or videotape from it.

Sue: The writing is an integral part of the whole process for you. On the other hand, it exists somehow autonomously. You’ve described ‘writing’ to me a couple of times, always as an open process. I think there’s a distinction between that and a videotape, which your audience receives very much as a fixed product, something with a specific beginning and end.

Colin: The great thing about writing is that it’s completely fluid all the time and can go anywhere. I hate production; editing is a little more interesting because it’s like writing again—you can start shaping and shifting because nothing goes directly from the written page to the final product. I’m always more excited to show people the writing than the finished work.

Sue: Is the fact that you’ve publicly connected your writing with your video practice—either, by creating this fictional critic or with this exhibition at the WAG where the scripts are an integral part of the installation—an attempt to resist the notion of closure that you feel people sometimes bring to viewing videotapes?

Colin: Yes, I think that I’ve always resisted closure. I was doing that even before I came across that word. I thought—oh, closure—what a good way to describe something I try not to do. So the scripts’ being there functions as two things: one, to show the genesis of the product, to show how it can be very different by the time it gets transformed into a tape or film—and secondly, to remind the viewer that it doesn’t just spring out of the air electronically and then transfer itself onto tape all by itself.

Sue: So you don’t wake up in the morning with a full visual picture in your head?

Colin: Never. Most scripts have come literally from one sentence that some person says or one image that I conjure up and describe. That one line comes from nowhere. For instance with Skin, I wanted to make something around AIDS, but after months of trying all kinds of different scripts I knew I wasn’t getting what I wanted. That was probably seven months of despair—even though I forced myself to write every day and I wrote volumes and volumes. I knew it wasn’t working and that there was nothing to do but keep on writing until it became whatever it was going to be. In fact it turned out to be entirely different from everything I’ve written so far.

Sue: Are you becoming a more confident writer? Do you enjoy it more?

Colin: I enjoy it more and I think I become better the more I do it. That’s probably true for every writer because there is a certain element of craft to it. But I think also I’m learning how to write more honestly and more directly. Within writing there’s a way you can romanticize a character. It’s irresistible sometimes to write witty lines or throw words together in a particularly enchanting way that just sounds great but in fact masks what it is you’re really trying to say. Often you have to throw out what you know are dazzling phrases because they don’t get at the core of what it is you’re trying to say.

Sue: You’re paring things down as much as you’re building a structure?

Colin: Yes. It’s amazing how you can avoid what it is you want to say. I mean I’m superstitious about saying what I really want to say right off because the whole thing might just collapse and go away. So I work towards it in that peripheral way. Sometimes finding the device is the hardest thing, even though you know what you want to write.

Sue: Are you able to say things in writing that would be more difficult for you to say in visual language—either performance or painting?

Colin: Absolutely, because I think everybody likes stories. If you can tell a good story instead of something that appears to be merely confessional or diaristic you probably will have an audience that is interested in what you are saying. If you can somehow bind the viewer up with a persona that makes them empathetic that’s a more interesting way to do it.

Sue: Are the viewer and the reader the same person?

Colin: Sure. Although what I think is unusual about this show is that for the first time people are actually going to be able to see the writing as opposed to the product.

Sue: So they become both.

Colin: That’s right.

Sue: In many of the tapes, and this goes back to your earliest work as well as to a work as recent as No Voice Over, one of the central elements is a written document. It might be a script, it might be postcards, letters, a newspaper article. For example, The Woman from Malibu is drawn from a newspaper article. Even your presentation about your own work was based on an article by a critic. The act of writing, the practice of writing, the reality of the written word in a text itself is very central for you and your way of looking at the world. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Colin: People’s lives are not a singular kind of narrative that runs a course and all makes sense. In our daily lives, we engage in several levels of narrative, some of which never complete themselves. Some may exist only for one day. Some we go into and out of over a long number of years—relationships with friends, lovers, parents. So the device that I’ve used when a postcard appears, a letter arrives, a telephone conversation occurs, sets in motion a reaction to that particular document or text. It just doesn’t sit there in mid—air. Someone receives it and adds to its content, responds to it. And that kicks off something unique because people will tend to write differently than they speak. By introducing a character through their writing you can cut enormous amounts of time and situate that character in a dramatic moment in their lives. You get to know a lot about them very quickly. The written document allows you to propel a narrative very suddenly out of that kind of situation.

Sue: The catalyst itself is something that is already constructed, something that’s already been subjected to interpretation and reinterpretation. Even, for example, the newspaper article, where the woman from Malibu is talking about her husband’s death—we don’t know how much is left out of that interview with her, to what extent those were really her words, if she really laid them out in that way—with that amazing detail about how far he fell off the mountain.

Colin: In fact she actually did. That was verbatim and what was so intriguing to me was her ability to give an emotional kind of shock with very rational, precise kinds of details around what was obviously an extraordinarily traumatic event. That’s what interested me about her. I had just moved to California and I thought gee, what will happen to her when she comes back to California? That kind of detailed observation seemed like a perfect way for her to talk about the culture that I was now both immersed in and observing. She became the vehicle for expressing all the eccentricities of southern California. She was white, middle class probably leisure class, her husband had retired, she could talk in an unquestioning, all-embracing way about the culture, the environment she was in. To me it seemed like an interesting way to comment as opposed to the artist, saying here is what this looks like. It was more fun to use her eye because she went places where artists would never go and did things artists would never do, like the Rose Bowl Parade and going to the recreational vehicle show. I imagined things that she would do and then I went out and did them.

Sue: You were able to get into her character when it was on paper. The Woman from Malibu is often seen as a demarcation point in your work because it was the first extended narrative. Was it the first script you wrote?

Colin: Yes, and I ended up playing the woman from Malibu sort of by accident. I didn’t know anyone in California, I had no money—it just seemed like a natural to play her.

Sue: Did you feel like the woman from Malibu when you were writing it?

Colin: The six tapes were produced over about seven months so it was a fairly continuous process. I was with Lisa Steele in California at that time and we would be driving down the freeway and sometimes I would speak but it would actually be the woman from Malibu’s voice or persona coming out. I became quite involved in her. That’s why I didn’t try to separate her from me in terms of appearance and certainly not in terms of voice.

Sue: How did the process work? Would you sit down and hammer out a script before each shoot, or did you do several scripts?

Colin: It was always a surprise to me that another tape was coming. The woman from Malibu would not shut up. She always had more to say. Often a script would be triggered by an event in the newspapers. For instance, in 1977 people on the freeways shooting people for no reason—or stories of transsexuals. Those events would become little markers around which I could weave another story from the Malibu woman’s daily life.

Sue: Were the scripts more immediate in the early days?