download the book or buy it here.

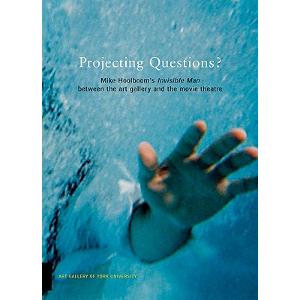

With the proliferation of digital projection, the presentation of moving images in art galleries has exploded exponentially in the process, the relationship of experimental film to the gallery circuit has shifted dramatically. This volume, coming out of Mike Hoolboom’s 2004 exhibition at the Art Gallery of York University, is a series of essays and conversations between artists, curators and programmers that delineate the complicated path from the white cube to the black box.

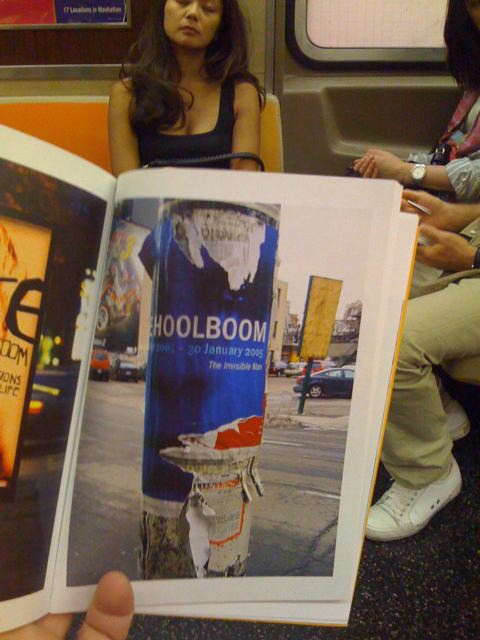

Published in connection to an exhibition of Mike Hoolboom held at the Art Gallery of York University on November 24, 2004-January 30, 2005. This 144 page book looks at the exhibition of movies in galleries (“the ideological framework that conditioned art projection” in Philip Monk’s words, with stops along the way to wonder about time, Godard, Douglas Gordon, the death of the author, swapping bibles for dictionaries, tsunamis of forgetting, cinema and its relation to other war machines, dreaming without pictures.

Mike Hoolboom has been called the finest fringe filmmaker of his generation. He has authored two books, Plague Years (1998) an anthology of his writings, and The Steve Machine (2008), a novel, and edited two books on fringe film practices, Fringe Film in Canada (2000) and Practical Dreamers (2008). He has won over thirty international prizes and two lifetime achievement awards. He has also been the subject of a dozen international retrospectives. The Invisible Man was his first public gallery solo exhibition.

Preface by Philip Monk – 11

Epigraph by Mike Hoolboom – 13

Paint it Black: Curating the Temporal Image – 18

Invisible Man Interview by Mike Hoolboom – 42

Searching for the Invisible Man by Chris Kennedy – 50

The Invisible Man Blog (February 2005) – 62

Showing Pictures (a conversation between Yann Beauvais and Mike Hoolboom) – 96

Complaints by Mike Hoolboom – 134

Preface by Philip Monk

I’ve long been a fan of Mike Hoolboom, both as a writer and a filmmaker. So sitting in the audience to one of his usually brilliant performance presentations, I had to exclaim “ouch” to Mike’s comments on “why are video installations so awful?” For I am a curator who has in part specialized in showing video installations in art galleries, mostly by artists but sometimes by real filmmakers.

To turn the discomfort around, we invited Mike to create a video installation at the AGYU based on his films. The texts here bear witness to the issue of video installation. The publication includes writing from opposing points of view that preceded this challenge and sets its context (my “Paint it Black,” Hoolboom’s “Complaints” and excerpt from “Love Rigorous”) and those produced for the project during or after it (“The Invisible Man Blog” edited and re-arranged by Hoolboom, Chris Kennedy’s “Searching for the Invisible Man,” and Hoolboom’s “Invisible Man interview”), as well as subsequent conversation with fellow filmmaker Yann Beauvais (“Showing Pictures”). Additionally, Steve Reinke’s “Hoolbus,” an audio interpretation of Hoolboom’s films that played on the AGYU Performance Bus in transit to The Invisible Man opening, is available on the AGYU website.

Thanks to Mike Hoolboom for taking up this challenge, Michael Maranda for editing, and Lisa Kiss Design for designing the book, and especially to Emelie Chhangur who coordinated the exhibition, toured it to the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery, and selected Steve Reinke for the Performance Bus.

Projecting Questions? by Dagmara Genda (BlackFlash, Winter 2010)

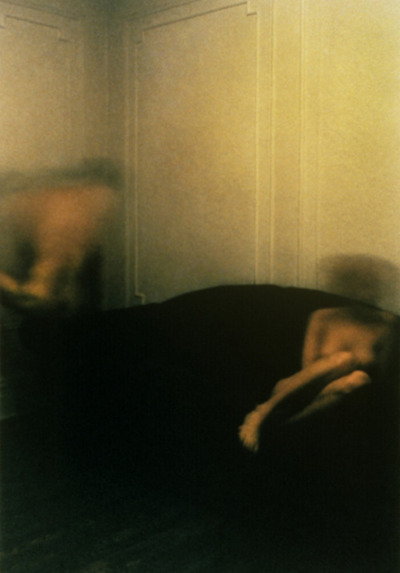

Projecting Questions? begins as a challenge, from both Philip Monk, the director of the Art Gallery of York University, and Mike Hoolboom, a Canadian artist working in film and video. Why are video installations so awful?” Hoolboom asks. Monk responds by inviting him to make one for AGYU. The result was The Invisible Man and its accompanying publication that covers the ideas framing the project but does not function as a straightforward catalogue. Its readability is not only due to its variety – the book is comprised of interviews, essays, blog excerpts and conversations – but is also carried in large part by Hoolboom’s very immediate and engaging writing.

The content is framed by Hoolboom’s chagrined “complaints” (which is also the title of the last essay) ”I know, I know, it’s a hateful way to start,” he writes as he launches into a list of video installation’s many flaws, from its dull fidelity to one idea and monotonous repetition to its firm rejection of any filmic strategy. Monk’s response is “Paint It Black,” an essay examining the uniqueness and merit of video projection, and most specifically the work of Canadian video artists Rodney Graham, Stan Douglas and Douglas Gordon. Monk makes the claim that if film was about movement, then video projection is about time. It reorders temporality in a way that removes it from film’s persistent present. After, Hoolboom presents a self-interview which is a revealing peek into the thought process of the artist. Later he laments that so many video works are slaves to the “idea,” forsaking “emotions, stories, flow.” Monk sums up their conversations quite well when he notes that Hoolboom lobs “poetics” to his “rhetorics.”

Projecting Questions? also consists of a more traditional essay on Hoolboom by Chris Kennedy and a conversation between Hoolboom and Yann Beauvais, a French filmmaker. Included as part of the project is also a website link to Steve Reinke’s audio interpretation of Hoolboom’s films entitled Hoolbus.

If I cannot characterize Projecting Questions? as a catalogue, I might be content in saying it functions more like a website. This is not only due to the fact that part of the book is a reprinted blog, but because it slips between images, styles, poetry and speculation with relative ease. It models itself after the way we might browse a web site, hyperlinking from one idea to the next, chasing each available tangent. As a traditional publication, it comes to read quite differently than a linear book. Rather than build an argument or a narrative, it guides us through an idiosyncratic passage of thought and speculation to reveal the dynamics behind The Invisible Man’s conception.