Going to Pieces Without Falling Apart by Mark Epstein (1998)

Can a parent leave their child alone without abandoning them?

This unstructured and unintegrated state of mind is the foundation of all healing.

The defensive nature of most of our mental activity.

We build up our selves out of our defenses but then come to be imprisoned by them.

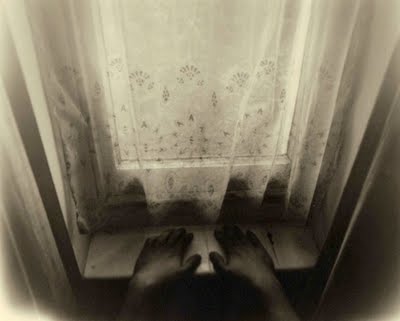

The capacity to be alone can only be developed with someone else in the room. Once it is developed the child trusts that she will not be intruded upon and permits herself a secret communication with private and personal phenomena. The best adult model that Winniccott could find for this is what he called “after intercourse,” when each person is content to be alone but is not withdrawn. This is a very unusual state because of how little anxiety exists. There are no questions about the other person’s availability, but there is also no need for active contact.

It is the mother’s function to create an environment for her baby in which it is safe to be nobody, because it is only out of that place that the infant can begin to find herself

Fearing the dangers of the past, she was preventing herself from having any kind of new and unanticipated experience.

Lucy was afraid to stop holding herself together. Lucy’s task was to reestablish contact with her capacity for unintegration, to heal the split between her coping self and the silent centre of her personality… Her task was to ask the lion’s collaboration.. to turn the internalized remnant of her abusive father into a protector of the dharma. She had to befriend him.

One of the most important tasks of adulthood is to discover, or to rediscover, the ability to lose oneself.

We discover what we need to say when we get out of the way of ourselves.

We yearn for the kind of connection that our own thinking guards against.

We fear that which we most desire – the falling away of self that accompanies a powerful connection.

Like an ever vigilant, overly intrusive chaperone, the thinking mind interrupts any possibility of connection.

As Freud described it, the thinking mind prohibits contact by “interpolating an interval” whenever possible.

Our own endless and repetitive thought squeezes the life out of life.

So much of our thinking appears to be boring, repetitive and pointless while keeping us isolated and cut off from feelings of connection that we most value.

When we take loved objects into our egos with the hope or expectation of having them forever, we are postponing an inevitable grief. The solution is not to deny attachment but to become less controlling in how we love. From a Buddhist perspective, it is the very tendency to protect ourselves against mourning that is the cause of the greatest dissatisfaction. As the great thirteenth century Japanese Zen master Dogen wrote in his discussion of what he called “being-time,” it is possible to have a relationship to transience that is not adversarial, in which the ability to embrace the moment takes precedence over its passing.

Freud (On Transience, 1915): “It was incomprehensible, I declared, that the thought of the transience of beauty should interfere with our joy in it… A flower that blossoms only for a single night does not seem to us on that account less lovely.” (But Freud’s walking companions are unconvinced. Freud realizes they are trying to fend off an inevitable mourning, in their obsessional way, they were isolating themselves and refusing to be touched. This is like our refusal to embrace the transience of everything that is important to us, including our own selves. They could admire the sights but couldn’t feel – locked in their own minds, unconsciously guarding against disappointment.

In Buddhism, breaking through the thinking mind’s isolation requires something other than just analysis. It requires a new way of being with the mind, one in which observing functions take precedence over its reactivity.

There is an apocryphal tale of James Joyce asking Carl Jung what the difference was between his own mind and that of his schizophrenic daughter. “She falls,” Jung is said to have replied. “You jump!”

Thoughts are like weeds, they can be pulled up by their roots and used to fertilize the garden of the mind.

In tracing thoughts back to their roots, back to the original feeling states, we get out of our heads and return to our senses.

In building a path through the self to the far shore of awareness, we have to carefully pick our way through our own wilderness. If we can put our minds into a place of surrender, we will have an easier time feeling the contours of the land. We do not have to break out way through as much as we have to find our way around the major obstacles. We do not have to cure every neurosis, ewe just have to learn how not to be caught by them.

Delusion is the quality of mind that imposes a definition on things and then mistakes the definition for the actual experience. Delusion creates limitation by imposing boundaries. In an attempt to find safety, a mind of delusion only succeeds in walling itself off.

As the practitioners of many martial arts often put it, we must learn to respond rather than react.

Stillness does not mean the elimination of disturbances as much as a different way of viewing them.

Can we let our unneeded defenses go to pieces?

Progress in meditation and happiness in relationship depends on my ability to bear disappointment.

He did not believe that her love could survive his aggression.

Sex: how to recast aggression in the service of love?

Love is the revelation of the other person’s freedom.

It was not what he thought it should be, but it was real.

Old age, sickness and death: three messengers that awaken people to spiritual life.

The mind is like a nugget of gold. Before it is worked on, it does not look like much, but if you know what to do with it, you can make it shine.

We do not get lots of realizations in our lives as much as we get the same ones over and over.

Open to Desire by Mark Epstein (2006)

Nisargadatta: The problem is not desire, it’s that your desire is too small.

The left-handed path means opening to desire so that it becomes more than just a craving for whatever the culture has conditioned us to want.

“All neurotics, and many others besides, take exception to the fact that we are born between urine and feces.” Freud

Noble Truths

Buddha: 2nd truth: cause of suffering is tanha – thirst or craving. The cause of suffering is not desire but craving.

Obstacles or “fixations” reduce desire to clinging.

Our tendency, under the spell of longing, is to try to take possession of that which we crave, to try to fix it, in both senses of the word. We want to preserve that which we desire, freeze it or trap it? We want to fix the run away quality that has us always in a chase.

3rd truth: desire can find freedom it is looking for by not clinging.

Desire recognizes the sense of incompleteness endemic to human condition. It seeks a freedom from this incompleteness in any form it can imagine: physical, sensual, emotional, spiritual.

Desire leads to the end of clinging.

When we discover that the object is beyond our control, unposessable and receding from out grasp… we learn to give the object its freedom.

Dharma: root word ‘dher’ – to hold firm or support. english word for throne: holds king). Latin words: firm, firmament, infirmary.

Zen: Kasyapa

The opposite of anxiety is not calmness, it is desire.

Anxiety turns one back onto oneself, but only onto the self that is already known.

There is nothing mysterious about the anxious state – an all too familiar isolation.

Ram Dass to guru: How can I know God? Feed everyone.

Ganesh: the lord (and remover) of obstacles. he appears at the beginning of things. The Guardian of thresholds between old and new.

Gap

Desire teaches us, not just by gratification, but by constantly undercutting itself, by never being entirely satisfied. It rubs our faces in reality by always falling a bit short of its goal. This is desire’s secret agenda: to alert us to the gap between our expectation and the way things actually are. In so doing, it shows us that there is something more interesting than success or failure, more compelling than having complete control.

The gap between desire and satisfaction keeps us longing for more.

How can we handle this gap? When desire is made into an object of contemplation.

Desire always disappoints, but we can make this disappointment the object of awareness, then the gap can be sweet (strawberries).

Three reactions to gap: 1. squeeze more out of what you have 2. addiction to distractions 3. turn against what you need

First three steps of left-handed path: entering gap between satisfaction and fulfillment, honestly confronting the manifestations of clinging and renouncing the compulsive thoughts and behaviors that clinging provokes.

In this tradition the active male desire, chastened by the gap that desire creates, becomes empathy or compassion. The desire to possess or control becomes the ability to relate.

Hungry Ghosts

Hungry Ghosts: their attempts at gratification make them hungrier.

Motivated by deprivation that has not been accepted, digested or metabolized, they tend to feel flawed, broken, unworthy of love. They take too much responsibility for what they feel, blaming themselves instead of understanding roots of trauma. In place of experiencing the pain of their childhood loneliness, they obsessively seek nourishment from people and things who can only disappoint, repeating the trauma instead of working through it. That is why renunciation is so important in the hungry ghost realm. Renunciation of clinging is the first step in grieving the pain of the past, the prerequisite for forgiveness and a more unfettered desire.

Renunciation by voluntarily forsaking compulsive patterns of thought and behavior where there are ongoing attempts to get unmet needs satisfied, it is possible to open up other pathways that prove more fulfilling.

Early trauma, whether in the form of parental intrusiveness, or abandonment, sets up a yearning for a relationship that can never be, while simultaneously driving people to reproduce their traumatizing relationships – replaying them over and over again in new interactions.

Sweet Bitter

Where possession is not possible, love can grow.

There are always three characters in a love story: lover, beloved, and that which comes between them – the obstacle (it is always clinging). Sweet bitter.

Desire can be maintained only if it is unfulfilled.

The desire to know oneself is often rooted in the feeling of never having been known.

Freud: therapy helps people move from neurotic misery to common unhappiness.

Love is the revelation of another person’s freedom.

Using food to manage her feelings.

Perform tapas: heat of asceticism, by guarding the sense doors.

Shiva and Parvati

In an infinite series of multiple lifetimes, the traditional Tibetan argument runs, all beings have been our mothers, and we can cultivate kindness toward them by imagining their prior sacrifices for us.

Treated as objects by well-meaning parents, they were still struggling for subjecthood. But their tendencies to view their parents as objects held them back.

When a child develops a false self in relation to parental pressures after a while they know only the armor, the anger, fear or emptiness. They have a yearning to be known, found or discovered, but no means to make it happen.

Gibran: Your joy is your sorrow unmasked.

Need

Male version of desire: possession, acquisition, objectification.

Self tries to get its needs met by manipulating its environment, extracting what it requires from a world that is constantly objectified.

Her fiancé’s need for her made it difficult to stay in touch with herself.

Japanese garden design principle: miegakure “hide and reveal.” Only a part of any object is made visible (creates a space, a distance, and that distance creates closeness)

Facilitating Environment

Winnicott: “It’s is joy to be hidden, but disaster not to be found.”

The most common psychological stance that we bring to our lives: the belief in ourselves as isolated, alone and in need, the attachment to the separate self. When we approach the world in this way, what we get from it is never enough. The object always disappoints, leaving us clinging to it or feeling rejected, thrown back into our isolated and insecure position.

In Winnicott’s view, much of our suffering stems from a lost capacity for this sort of waiting, an exclusive reliance on the male, object-seeking, mode of relating.

Desire cannot always be satisfied by attacking the problem, or by trying to possess or control the object.

Play is child’s work.

Play is the child’s natural mans of coping with disconnection that threaten but do not become trauma – a template for what is possible when desire comes up against the gap between satisfaction and fulfillment.

Two kinds of people: those who enjoy desiring and those who require satisfaction. One clings and the other doesn’t.

Like Freud’s friends, most of us are conditioned to look for fulfillment for our desire. When it is not forthcoming, or not lasting, we tend to withdraw. Rather than rejoice in our lover’s evasion of our attempts to control them, we feel dejected. In the face of unreliability, we retreat into our selves. Our mourning paralyzes us and our desire gets derailed.

It is possible that desire is valued, not as a prelude to possession, control or merger, but as a mode of appreciation in itself.

A facilitating environment is one that a parent creates for a child in which the child’s defenses can be let down, when a child can “simply be” without worrying about keeping things together. In a facilitating environment, a child is free to explore his or her own inner world, to try to come to terms with the paradoxical nature of separation from and connection to the parents. The facilitating environment promotes growth because it gives the child room to move away from the parents while staying present enough not to provoke anxiety. It allows a child what Winniccott called “transitional experiencing.” The key to understanding transitional experiencing is child’s play. When a relatively secure child plays with his or her toys, the entire room comes alive. It is not a question of “self” playing with “objects” but of an animation of the entire space.

Eightfold path

Ethical foundations: right speech, right action, right livelihood. Meditation foundations: right concentration, right effort, right mindfulness.

Wisdom foundations: right understanding, right thought.

Gods

Emotions are like the gods of the old world, linking us to our souls. When we repress them, we are totally cut off, and stuck in our impoverished selves. But when we identify completely with the emotions, when we think they are us, we are letting the gods trick us. In either case, in repression or in possession, we lose the capacity for wonder that our emotional lives make possible. Desire is one means of keeping us in contact with this wonder.

Anger

Developmentally, the central task of the infant is to make sense out of the fact that he or she both loves and hates the same person.

When the mother makes room for the child’s aggressive pursuit of her, he can learn that she survives his assault. Out of pursuit comes recognition of the other, and out of recognition comes empathy. In Tibetan Buddhism, aggressive male desire is represented as an agent of compassion.

In erotic life, a second opportunity is give to experience the entire range of love and hate, converging in the body of another. While many couples are either frightened by this prospect or are unable to contain each other’s rage, the possibility is there to experience the empathy that comes from the survival of mutual destruction. Anger is what makes the beloved knowable in his or her subjectivity.

Erotic love unites two streams: one that wants to take over the other, to devour or destroy it and another that wants to give it its freedom.

In couples who try too hard to keep their anger at bay, the first casualty is usually their erotic connection.

Sexual relations let us act out the passion of the infant and the survival of the mother.

Women

In her now classic book on woman’s desire, the psychoanalyst Jessica Benjamin described this missing element very well. She recounted a poignant vignette. Two psychologists, one of them the mother of an infant boy, were strolling by the hospital nursery one day when they stopped to peer through a glass partition at the other newborns. On each bassinet were pink or blue labels announcing the sex of the child for all to see. The blue labels for the boys jauntily announced, “I’m a boy!” but, to their astonishment, the pink labels for the girls did not correspond. Instead of “I’m a girl!” the pink ones read “It’s a girl!” All the boys were “I” and all the girls were “It.” The boys were given a subjective voice, the voice of desire, but the girls were offered to the world as objects. The sight of the baby girls, already bound by society’s preconceptions, was an epiphany for Benjamin. Freud’s perennial question, “What does woman want?” was not phrased correctly, she concluded. The question is not what do they want, but do they want, at all. Do they have their own desire? Or perhaps the question might be more correctly stated: Can women be their desire? The challenge for women, she decided, is to move from being just an object of desire to becoming a subject: she who desires.

We can be different – less defended, more relaxed, more porous and open, simple, easier and still ourselves. And the route to this change is not by cutting off desire, but by expanding our usual understanding of it.