Notes from a talk by Michael Stone at Centre of Gravity on July 19, 2012 on day 11 of a 12-day intensive.

Integration

If you pare down the Heart Sutra to meditation instruction, it says: sit like a Buddha. And then when you get a feeling for the Heart Sutra there’s no “like,” it’s just: Sit Buddha! Buddha means to be awake, from the word bodhi – the bodhi mind is an awakened mind. The Buddha is not a person but a way of being here and now. You are the place, the empty place where the entire world converges. To feel that in sitting practice means there’s listening and sound – you can feel the restlessness (dukkha) when listening to a sound sometimes, as if the sound is somehow outside of you, as if it’s over there. But when you’re paying attention to what you’re saying about listening, to the story you’re telling about the sound that occurs – all that’s left is the images you create. And when you can drop those pictures there’s no separation between listening and sound, then you’re in samadhi or integration. There is spaciousness, intimacy and love (not an idea of love, but the feeling of being held by the universe). Then the mind comes in and tries to figure out what just happened and the experience dissolves.

Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara

“I remember a friend who was dying of liver cancer; he was very uncomfortable – an older man, in his 70s. He was at a retreat that I was leading in Philadelphia and he told me he was only going to stay for the morning, but he stayed all day. I asked, “Ed, why did you stay?” And he said, “Well, I was sitting next to this young man and he was so fidgety. I thought if I just sat next to him, and if I was very still, it would help his practice.” So Ed sat there all day long like a Buddha. Like a Buddha? Ed sat there all day long. And that’s what we do in our practice: we have no idea how we are affecting the person next to us. We sit there and we allow our chest to be open, we allow our energy to circulate, and we have no idea what that’s doing around us. It’s a wonderful thing!” (from A Winter Sesshin, Ten Talks on the Heart Sutra)

We have no idea about the effects of our practice. To feel the stability and the instability of the practices around us in the room. I’ve learned so much from Norman Feldman, I’ve been fortunate enough to lead some retreats with him, and am often able to sit beside him in meditation. Twice he’s come back from month-long retreats in India, and he’s dozed off! That was so powerful. He’s exhausted, but still he makes his way to the front of the room and sits on his cushion. You don’t fight it, you let it move through you. The key part of practice is to admit a shift in how you see yourself, how to view yourself from another perspective. This is what we’re doing at the end of a yoga practice in savasana. We’re rolling over on our sides and we’re letting go of the corpse pose. We’re shifting. We’re not holding on to something.

Bell

When you have the job of ringing the bell you need to tune into the room. Sometimes the room is really sloppy – ring that bell loud! Sometimes it is very unified and quiet. Whether you ring the bell loudly or quietly, there’s nothing personal about it. It’s not a punishment or admonishment, it’s a way of returning to this moment.

Emptiness

In “Infinite Circle” Bernie Glassman writes that emptiness is just everything, just as it is right now. Han-Shan: “All this depends on the meditator who in the time of a thought can achieve the correct conception of the heart.” Emptiness means becoming the space that can hold a thought without grasping or pushing it away.

In the Heart Sutra Avalokiteshvara lists the major Buddhist doctrines: the skandhas, 12 link chain of dependent origination, 4 noble truths, enlightenment – and pronounces them all empty. Empty of what? Empty of “own being”. We are in the water world. We are much more like rivers than concrete. Emptiness means to course in that flux.

Restless

The Heart Sutra acknowledges that we have suffering – dukkha – a word that I’ve been translating lately as restlessness. Even in moments of happiness we experience a little bit of restlessness. Why does happiness give rise to it? Because we want to hold on to it. If something is good, we want a little more, or we want it to keep happening. And if something is bad, we want to rush away from it. We’re either rushing towards or rushing away. Restlessness is built into everything, good or bad, because there’s grasping. But a lot of our lives is ungraspable. We have unresolved conflicts in our life, in our familial life. We’ve been through inexplicable experiences, good people we know have died young.

In early Buddhism the cause of suffering, the second noble truth, was thought to be desire. The secular movement has undone that teaching, but I still like it. The origin of the cause of suffering has to do with our habitual, unconscious desire to grasp our experience, to make things stay the same, to hold on. And this grasping is already a kind of dying, because it separates you from what is happening now, in other words, it separates you from love. The third noble truth is to see the way we want to keep things the same, and how desire can’t make anything last.

All past, present, and future Buddhas live Prajna Paramita

And therefore attain Anutara-Samyak-Sambodhi

Anutara: unsurpassed. Samyak: correct. Sambodhi: Awakening

Mystery

How mysterious to have these Sanskrit words appear in this largely English text. We chant it, and maybe we don’t know what we’re chanting. Because we can’t finally know. Because there’s always something outside, beyond our ability to grasp. Or? Whenever you’re reading or talking or listening you’re translating. And when you read a book, for instance, it’s important to go down into the places in the text that are cold, shadowy and rocky, where it’s difficult to understand, where there are viewpoints that are different from your viewpoints. If we stay in the sunny, easy places, we only wind up hardening around our views. The warm places are the ones we already know. In the Heart Sutra the rock places are: form is emptiness. And then: anutara-samyak-sambodhi.

In a yoga pose, you need to plunge all the way into it, until you don’t know what it is anymore. If there’s too much flow or too much prana, there’s no integrity. If there’s too much strength, then it becomes rigid.

Anutara-samyak-sambodhi means there’s nothing to fear. Don’t be scared. Even if there’s some fear, you can hold that fear, and move forward.

So set forth the Prajna Paramita mantra,

Set forth this mantra and say:

Gate Gate Paragate! Parasamgate! Bodhi Svaha! Prajna Heart Sutra!

(meaning: Gone. Gone. Utterly Gone. Really gone. (The best gone. The vivid gone.) Yippie! Awakening.)

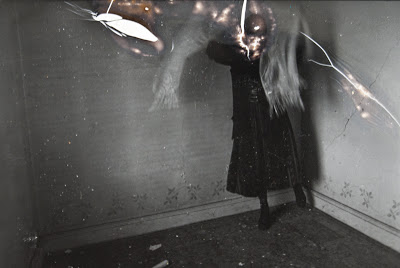

This is how the Heart Sutra ends, with a burst of fireworks and flowers. It becomes magic, voodoo, incantation. Maybe the Heart Sutra is not a summary philosophical text after all, but a magic text that leads to celebration. When you need a mantra in your life to calm you down, when your friend dies unexpectedly or expectedly, when the impossible becomes your new home, you can chant this mantra: Gate Gate Paragate! Parasamgate! Bodhi Svaha! Prajna Heart Sutra!

This line offers a celebration – what a beautiful life this is. Maybe you need to do this because there’s ghosts that you need to leave behind. Perhaps you could do this chant for them. Gone. Gone beyond. Gone beyond beyond. The only expression of emptiness is in form. You can only surrender in form. This mantra says yes to form. And yes to emptiness. There is emptiness, and at the same time I have this body, and this heart, and this family, these parents, these kids. My son is incredibly creative and at the same time he’s the most stubborn person I’ve ever met. Where does he get it from? That’s the form – but he’s not always stubborn. And he’s not always creative. There’s no need to idealize, to inflate and deflate.

Freeman

Freeman Dyson, 88, is a pioneer quantum physicist, pure mathematician, metaphysicist, beady examiner of such givens as global warming and tireless explorer of our future as bio-engineering space colonisers. A Fellow of the Royal Society for 60 years, he left Britain at the age of 23 because he believed “Americans held the future in their hands and that the smart thing for me to do would be to join them.” When he took up his post at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, Einstein was still working there. Startling propositions and inconvenient arguments are the signature of this human neutrino, widely regarded as one of the Nobel Committee’s glaring omissions.

I e-mailed to ask him: (1) why he remained hard at work; (2) what were his strengths and weaknesses now compared with earlier in his career; and (3) what advice would he give to those who have been working for (a) one year, and (b) 30 years? This was his reply, received the next day:

Thank you very much for your friendly invitation. I am delighted to share with Her Majesty the distinction of hanging on longer than expected. Here are brief answers to your questions.

1. I continue working because I agree with Sigmund Freud’s definition of mental health. To be healthy means to love and to work. Both activities are good for the soul, and one of them also helps to pay for the groceries.

2. In my younger days my work as a scientist was deep and narrow. Now, as I grow old, my work grows broader and shallower. As a young man, I solved technical problems of interest only to a few specialists. As an old man, I write books about human affairs of interest to a broad public. In both halves of my life, I tried to make the best use of my limited abilities.

3. (a). Advice to people at the beginning of their careers: do not imagine that you have to know everything before you can do anything. My own best work was done when I was most ignorant. Grab every opportunity to take responsibility and do things for which you are unqualified.

(b). Advice to people at the middle of their careers: do not be afraid to switch careers and try something new. As my friend the physicist Leo Szilard said (number nine in his list of ten commandments): “Do your work for six years; but in the seventh, go into solitude or among strangers, so that the memory of your friends does not hinder you from being what you have become.”

From INTELLIGENT LIFE magazine, January/February 2012 by Charles Nevin

Mantra

Mel Weitsman: “The goal is to be where you are and allow enlightenment to express itself… So, what is a mantra? We think of a mantra as a few words that you repeat over and over, but mantra is like our activity. A true mantra is not just repeating some words over and over, but the way we actually move in our lives is our mantra. Our practice is our practice. The Prajna Paramita mantra is the mantra of practice. In a narrow sense, it’s how we enter the zendo every morning and sit on the cushion, chant the sutra, and bow, and move. This way is actually “mantra,” the mantra which induces prajna. When we offer incense we invite prajna to permeate our activity, and we invite Buddha to join our practice. If you look at the rhythm of our life, no matter how rough or smooth our life is, there is always a rhythm, some kind of rhythm, and the rhythm of our life is the mantra that we are always reciting. So, what kind of mantra do we want to recite? How can we recite this mantra which induces prajna through our activity day after day?

I used to watch Suzuki Roshi’s activity, you know. When I first started to practice, I remember that I was amazed because my life was so loose and I came to the zendo and I saw this little guy who would come out of his office every morning, offer incense and bow, and sit on the cushion, and do zazen, and all the things that you do, and then go back to his office. At the end of zazen, we would file out and bow to him on the way out, and he would always look at us and bow. Every time I went to the zendo he was there, and he did that. I thought, ‘Well, he does this two times every day and he doesn’t seem to get tired of it.’ His activity was so different from mine. In my activity, I never wanted it to repeat more than once or twice, but his life was this life of continuously doing the same thing over and over again, and bringing something extra to doing it, too, you know. I realized that the way he lived his life was like a mantra. The activity of his life was very narrow, but, within that narrow parameter of his life, his life was very rich and satisfying. He didn’t need to occupy himself with other things to entertain himself. He had complete satisfaction from doing what he did completely. It was very impressive. That is our mantra, our practice. ‘So proclaim the Prajna Paramita mantra…’ through our activity. We don’t chant this mantra very much, except during service when we recite the sutra, but the mantra goes on in our life day after day.” (Heart Sutra Part 7, Sesshin lecture given October 26, 1994, Camp New Hope, NC by Sojun Mel Weitsman, Abbot of the Berkeley Zen Center)