What Is Felt Cannot Be Forgotten: an interview with Deborah Stratman (2009)

When she raises her camera, seeing is already thinking. Yes sure there is the raw delight in watching the light well up inside the body of the visible, but always these views are pointed (in the Roland Barthes sense of the punctum, they are sharp, they poke, they wound their viewer, which is her first of all, and then us.)

She has tried on different kinds of making, there are documentaries about street racing in Chicago, a circus troupe in China, and found footage missives which take aim at a gendered divide, and more besides. She is not like a boy who casts the same variations of fingerprint again and again, and yet, at the same time, in all her work there is a quality of watchful attention, an outraged politic, an experience lived through the body and searched out again through her camera double. It is only space constraints that keep us from presenting Deborah’s loquacious, witty insights into each and every one of her movies, the real estate of the page permits discussion of only three. So I invite you to imagine the before and after tellings, as if arriving at the scene of an event which is already underway. We enter mid-stride, in the midst. A restless searching, an appetite for pictures without end.

MH: On the Various Nature of Things (25 minutes 1995) appears as a series of science riddles. Set in six parts (gravitation, magnetism, heat, cohesion, erosion and illumination) and narrated via the journals of Michael Faraday (1791-1867) (though self taught he was responsible for the magnetic field, the use of electricity and much more), your fragmented presentations present a series of audio visual puzzles, one quickly giving way to another. In “Gravitation” a fish is chopped while Faraday riffs about “power.” Can you explain the upside down/motion picture dinosaur which follows this? And draw a connection between the underwater life, the unmade bed, and a cup thrown against an outdoor fire place (?) which is met by the sound of a canon going off, as if a whole pantry had been tossed. Are these all opposing instances of gravitation?

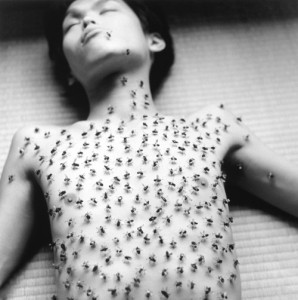

In “Heat” bees pollinate flowers while Faraday describes a melting block of ice. Why? There is a keen attention to light here, a jittery nervous camera plunges past a vast forest fire and city lights, what are these night fires, and why the hyperbolic camera stylings? In “Cohesion” you produce a flickering pan between a man holding a spinning globe and sheets of paper pinned to the ground. Are these the names attached to nature (which ‘cover it up’ so that it can’t be seen?) In the closing chapter, Illumination, Faraday’s stand-in remarks, “You see the screen remains dark,” while you show us a white screen. Is this because overexposure is also a method of concealing, that light can be used to illuminate situations but also to mask and disguise?

DB: Faraday is one of my heroes. Along with his advances in the field of electromagnetism, he also developed the phenakistoscope, that cinematic forebear. It’s one of those rotating cylinders with slots cut into it to which you peep through to see incremental images on the inside wall appear to move. He was interested in persistence of vision. If you’ve never had the occasion to read Faraday’s populist lectures, I’d highly recommend them. They’re funny, adroit and illuminating. I found a book transcribing his Christmas lectures at the library and was struck by the way he (or Science in general) sought to apply taxonomies to the chaotic conditions of everyday life in order to grasp them or make connections between phenomena. I thought, well here is a system I can appropriate for my film, because I was struggling at the time to reign in what was becoming a very unwieldy aggregation of footage.

I think the system I choose is equally matter of fact and totally absurd. There are many instances, some of which you point out, when the category of “Force” and concurrent footage are plainly at odds. And other times where a connection can be made, but only in an emotional or metaphorical sense. “Erosion” can allude to geography which succumbs to the elements, or a failing relationship. “Gravity” can speak to the attraction of objects to one another, or gravitas. All of the forces, in fact, are as poetic as they are scientifically specific. We are interned by these laws, they govern us, as Faraday says, and yet lyricism provides us a means of escape. I suppose that is the main theme of the film.

The film is filled with riddles, so it feels a bit like cheating to solve those that seem opaque. Like Raoul Ruiz, what interests me are the possibilities of misunderstandings between what is seen and what is said. But I’ll have a go at a few… Holding a lens up to the image of the heavy dinosaur beast is a way to let him defy gravity. The sequence in “Cohesion” with the globe-holder and paper-pinner is about the futility of giving names to things. Mapping and naming are not necessarily knowing, but there is a beauty in the way they work. When Faraday states that the screen remains dark, though we see a screen that is white, it points to the way overexposure can conceal, and prods us to question where truth lies. If we see one thing while being told another, what do we do? Why should we trust the voice of reason?

As for the hyperbolic camera work I was going through a phase where the camera accompanied me everywhere I went. Camera movements were Vertovian extensions of my body, or of my emotional state. I was cine-writing, enamored with the streaks and strobes and flares I was getting. When I think back about holding the camera then, it almost seems like I was divining. It makes me think of those Asian mediums who intuit messages by grasping small chairs that flail violently about as they cipher virtual characters on a surface. Like an overly aggressive ouija technique. I miss the naive trust I had in light and movement and intimacy then. It’s something I’d like to try and get back to.

I think the film is both dark and joyful. It’s a kitchen sink film, an encyclopedia of sorts, searching for a way to catalogue what I was seeing and hearing and wondering at. I was trying to be equally true to my intuitive grasp of the world, and that of Western science, and the cinematic apparatus itself. There are twenty four chapters as a nod to the constraints that film applies to time.

MH: Untied (3 minutes 2000) shows a tight rope walker (a theme you would take up four years later in Kings of the Sky) and then a man and a woman fighting, over and over. The found footage collage continues with a child lying (dead?), a man kissing a woman’s hand, another couple fighting, seen through a door’s peephole. And then a flickering lampshade. The home is a war zone, the gender divide irreconcilable. The final enigmatic shot offers a sled skimming across the ice. Is there no hope?

DB: Hope. Lately it seems so last century. Gone the way of walking, like those Romantic poets who composed best at three miles per hour. Gone the way of politicians and newsmen who were ugly and could write their own speeches. Gone the way of real sugar and butter. Or of film celluloid.

But yes, definitely, there’s hope. Though in the case of this film, it’s much closer to 60 mph than three. That’s what the final shot is all about for me. Being released. Shot out into the unknown. Set free from the debilitating rigor of unhealthy relationship patterns to an unwritten place where self-definition can start afresh.

When I shot that particular footage which you surprisingly and delightfully describe as a sled skimming across the ice, I think it may have been the first time I had ever visited the Great Salt Desert in Utah. I’d had that particular image for years before I made this film, never knowing quite what to do with it. I have visited the salt tundra many times since, but that first visit was unforgettable. The white flat expanse tabled before you in all directions. The loss of familiar context and scale is glorious. I suppose being way out at sea must be similar. There’s such a rush from being able to drive without adhering to a road. It made me think about how radically altered our surroundings and our thinking have become over the past couple centuries since the land became inexorably scarred with the linear geometries of motorized travel.

“Untied” is about the sensation of being untied. It’s about the record needle that finally gets lift out of its stuck groove. It was made partly in response to a series of violent accidents that had left me immobile and house bound. It was also a kind of farewell to a failed relationship that had taken too long to let go of. Like so many things.

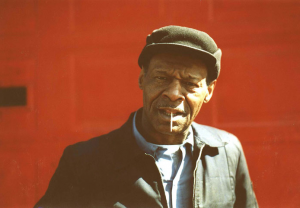

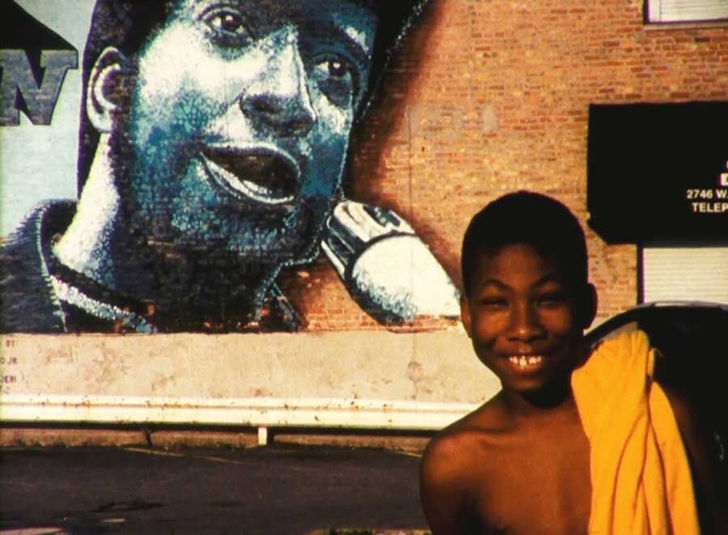

MH: The Blvd (63 minutes 1999) is a slice of impressionistic urban ethnography looking at street racing in Chicago. Over and over you are the only woman in the scene (though you are behind the camera, not in front of it, occasionally heard replying). Can you talk about how being a woman helped or hurt you in gaining access, or what it meant being a white woman in a mostly black world? The traditional doc approach is to establish “characters” whose “story” we can follow. Instead you offer us a collection of fragments: a mechanic and his garage, visits to a late night diner, gambling moments, curbside views of the races, spectators. What does your approach gain that the other leaves behind? Could you talk about the phenomena itself? There are so many gathered to watch, streets are blocked off, how is all this organized and does it persist?

DB: The phenomena of street drag racing is totally riveting, and yes, it persists! I was fascinated by the ritualized spectacle of the race, and by the devotional attention put into the cars. It seemed incredible to me that so much time and energy and passion are spent on something so immaterial and transient. I think speed might be a bit like faith, a new kind of belief.

Logistically, the guys have a number of spots where they might stage. They basically wait around until someone sets up a race. Then everyone places bets and drives en masse to some pre-determined location where the race happens. The racing tends to be very in-and-out because nobody wants to get caught. Their cars could get impounded and it’s a very steep fine. So the area where people stage or hang out is generally not the same place where the highest stake street races happen. They try to find well-paved quarter-mile spots without intersections. If there are cross-streets, bystanders will block them off with their cars so nobody will drive through unknowingly. There are other, more casual races that will go off one after another at popular, crowded spots where onlookers come every weekend. These are the spots where the cops open all the water hydrants—you can’t race on a wet street. If you got to a street where all the hydrants were on, you knew you’d missed the race.

I do think I establish two characters, though we don’t follow their stories in a linear sense. One is Tim Mullins, my mechanic/neighbor who is a master storyteller. I could listen to him for hours. The other character is Chicago’s west side, at night. Tim’s garage is closed now, but when I moved into the neighborhood ten years ago, it was still open. His garage was an amazing node where people were constantly stopping by to check in and catch up with local news and gossip. Of course, the place was always busy with ailing cars, but plenty of people stopped in just to visit. Tim is a very perceptive, generous person. He was always finding work in the shop for people who were broke or adrift. As a result, the place had a baffling and constantly rotating ensemble of employees.

In the video, I return to my “characters” in the same way that visitors stop in at Tim’s garage: sporadically, maybe a little impulsively, not following any narrative arc, looking for someone to share news with. I thought of the garage and the emptied city scenes as moorings to loop periodically back to. Tim’s garage grounded the neighborhood, and was especially salient to me since he had been a big racer himself.

Most of the neighbors have left since I made the film. The Henry Horner homes which were a big public housing tract one block south of me have all been torn down. And when Tim closed up the garage, it felt like the pumping heart of the neighborhood packed up and split. The empty building is still there. It’s kind of sad.

As for being the only woman, there were always a few others, so I never felt particularly isolated or vulnerable. Also, it’s important to note that on most of the shoots I had collaborators with me. Jay Cookson shot a good deal of the footage as a second camera person. And Melinda Fries and Wheat Buckley often came along as sound recordists or assistants. Some of the most interesting footage I got was when I was working with Melinda. I think this was because the presence of two women with a camera seems an innocuous, curious anomaly. When Jay was shooting, the men were pretty guarded and cagey. People would ask him what TV station he worked for. I was never asked. I didn’t come off as professional. But that led to more comfortable interactions with the people I was filming. Sometimes pervasive stereotypes can really work in your advantage.

I was keenly aware of my whiteness. I was (and still am) self-conscious about the hazards of my white self representing black others. But I wanted to make this piece despite my apprehension. Mostly because when I first moved back to the States after five years living in Iceland, Latvia, Russia and Denmark (cultures decidedly remote from my own), I needed to make a piece about my local Chicago neighborhood. I tried to be honest about including myself and my aesthetic, so that I’m a known quantity to the audience; so that the gulf between filmmaker and subject can be approached from a place of some knowledge instead of pure speculation. Still, scenes harbor different things for different people. For instance, I have always loved the introduction to Tim at the beginning of the film—where he walks towards the camera and asks what kind it is and then takes the camera and shoots his friend dancing and goofing off, and then films me, and then hands me back the camera, which we see via the shadow. But I recently watched that same scene with three of my black students and they were totally offended by it. In their opinion, I was perpetuating the stereotype of the technologically-stymied and jig-dancing black man. And in a sense, they’re right. I had never considered that sequence before in that way. I think the scene speaks perfectly to my relationship with Tim, and to his relationship with the employees, and to his sense of humor, so I don’t regret including it. But I felt guilty (and complicit) about not seeing the potential implications of that particular series of images in terms of the larger history of representing blackness.

Some really incredible things happened during the making of that film. The most exciting to me was that five or six of the guys who were part of the crowd I was following got their own cameras to document the races. I can’t think of any better outcome of a documentary gesture towards a community, than people from that community taking representation into their own hands.

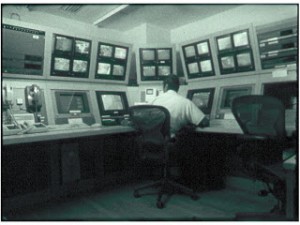

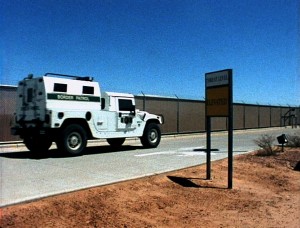

MH: In Order Not To Be Here (33 minutes 2002) begins with a terrifying surveillance video offering an aerial view of police (or border patrol? Soldiers?) gathering up folks in the dark. The camera has a voice (the sound of the eye) which is used to locate the people targets, and guide cops on the ground. And of course, for those trying to cross the border, it similarly sees what they can’t see, that their moments of escape are rapidly dwindling. Where did you find this footage?

DB: The footage you see at the beginning of the film came from the Collier County Sheriff’s Department in Florida. To get it, I placed a lot of cold phone calls to a lot of sheriff’s departments. It’s a bit hazy in my memory now what made me decide upon any given department. I vaguely recall researching and compiling a list of police departments who employed helicopters. I told them I was an instructor (true) teaching a class (true) about new ways that technology, and specifically photography and video, are employed by law enforcement to aid with forensics or in pursuit of their ‘targets’ (not exactly true – though a few years later I did teach a photo class about the history of the image as evidence called “Collecting Visible Evidence”).

I was very specific with the officers about the footage I was looking for. It needed to be an assailant on foot. The discrepancies in scale and power between the robotic police machine eye and the vulnerable metabolic body had to be explicit. It needed to be at night, employing infrared so the figures became spectres. The pursuit needed to be as long as possible. My line was that I was giving a lecture where I wanted to have some visual examples of just what FLIR* technology was capable of. (*A FLIR unit is a gyroscopically mounted camera on the undercarriage of the helicopter. It’s controlled by a tape operator on the inside with a kind of joystick. It’s basically an airborne steadicam.) What I was in essence trolling these law agencies for was the image I ended up staging at the end of the film. I kept asking them for pursuit footage that followed a runner who jumps in the water. Unsurprisingly, nobody had this. When I realized I couldn’t find what I wanted I decided to shoot it myself. Also, and this is critical, none of the departments had footage, at least that they were willing to admit they had, of the pursuant escaping. The film wouldn’t work if the fleeing runner didn’t ultimately shake his pursuers.

Anyway, at some point, a Florida agent told me he had exactly what I was looking for, and sent me a VHS compilation tape which including the scene I used in the film. The dogs were a revelation for me. They brought up such tactile mental imagery, escapees running through swamps, heaving breath, acrid smells, the terror of knowing the pack had your scent. And they were a nice portent of the menacing dog footage that occurs later in the film. I was also taken by the fumbling blindness of the K-9 officers trying to heed the directives of their airborne colleagues, whose frustration is hilariously evident.

When I was first collecting this footage, border crossing had not entered my mind at all. But it suggested itself anew with each viewing. I’m pleased that it slips towards that interpretation.

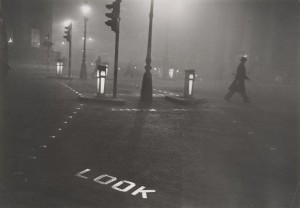

MH: You follow up with a night time vigil showing emptied streets, walls, police wagons passing at night, a searchlight illuminating moments of a middle class home front, and then moments of the perfect life inside, the overstuffed chair, the recipe book held open by a machine. The fragile compact of home, walled up, fortified, dogs baying at night. We don’t know who you are but stay away from our overstocked kitchens, our garages bursting with cars, the booty lining our closets. Where are we and why did you shoot only at night? What led you to render this exposition of every day fears, recasting the bright facades of American commerce as menace and threat?

DB: Yes, these images are a ‘vigil’ in their mute, unyielding gaze, holding out for some unstated spiritual shift, as if I were filming from a hunting blind. It’s the emptiness of the locations which goads the camera to continue the vigil. I chose to shoot at night because I needed the locations empty to suggest the metaphysical hollowness I experienced in the design of these communities. As a kid who grew up in the suburbs it was a feeling I struggled with for years. These are not spaces designed for interaction or bodies. They are not walking communities. In fact, they’re not communal in any way. People move from their houses to their garages to their cars and leave for work inside their steel and glass bubble. The absence of a public commons removes the soul from these places. They have as much heart as a parking lot.

This need to portray emptiness was very much a reflection upon my own psyche, the lack of conviction I had been feeling, the loneliness of being human. For a long time the film wasn’t going to be about the suburbs at all. It was the hollowness I was after. Corporate and suburban planning eventually became the vehicle through which I felt I could get at this void. It’s a problem, no? How to convey spiritual bankruptcy or moral hollowness via material things? How to film numbingly bland places without boring the audience to death?

There’s a secondary reason for filming at night. The sites take on renewed depth with all those different color temperature light sources, and facades falling off into darkness. Plus, I’m extremely partial to the eerie buzz of fluorescents. I tried shooting during the day and it was terrible, sickeningly flat and quotidian.

MH: The film ends with a seven minute sequence showing a man running at night, seen in negative, while newscasters describe a house fire and cop shooting in Los Angeles County. I’m guessing you staged this to rhyme the opening, then laid the radio audio underneath. Can you talk about these decisions and how you approached the shoot?

DB: The audio is actually a combination of three sources. One layer is the live audio recorded during the shoot through the helicopter’s two-way system. If you listen closely, you can hear me giving directives to the camera operator. I was sitting next to him in the helicopter. You can also hear static and snippets of air traffic communication. The second layer is electronic music composed by Kevin Drumm which riffs off the sound of the helicopter. The emphatic pulsing literally raises your heartbeat which is why that final sequence is so gripping. It’s totally physiological. Kevin is an incredible composer, I discovered his work by accident in a record store in New York, and it turned out that he was virtually my neighbor in Chicago. I contacted him out of the blue to see if he would be game to collaborate on a film project, and to my (and the film’s) good fortune he agreed. The third layer is sound taken from a CNN news report about an event that occurred in Valencia, California where I happened to be teaching just prior. Valencia is an upper middle class, extraordinarily ‘master planned’ community about fourty minutes north of Los Angeles. Just after I left a local, who had been passing himself off as law enforcement, and who had amassed a huge arsenal of weapons, had been found out. Officers and then eventually SWAT teams were sent in to try and extract him from the house. He died inside rather than surrender his fortress and identity.

I included this story because I wanted the running figure to potentially be this Valencia man. At one point one of the agents interviewed states, “Maybe he did escape, maybe he did survive the fire. We want to make sure it’s safe…” I wanted the running man to be many things. I wanted him to be us. I wanted him to be an illegal immigrant. I wanted him to be an escaped slave. I wanted him to be a Columbine killer (the full fourteen minute-shot actually opens with the runner bursting out of a school). I wanted him to be the guy we’re rooting for to shake the overbearing panoptica of contemporary society. I wanted him to be the human who is missing from the rest of the film. The one we’re placing all our bets on to make it out of our hyper-controlled environments. The scene was also an oblique way of paying homage to JG Ballard and his novella The Running Man. The book, especially its location descriptions, provided me with some much needed threads early on in the conceptualizing of the film.

The running man is the core of the film. He was played by my friend Joaquin de la Puente, who was the only person I knew at the time in good enough physical shape, and crazy enough, to run so far without keeling over. I didn’t have enough money to rent a helicopter, so I trolled around for months until I found a local guy who contracted his helicopter to Fox news for their daily traffic reports. He offered a free ride if I could map out the shoot to happen on the way back from the morning news. Joaquin and I scouted around near the heliport and mapped out a run that would include a school, suburban lawns, parking lots, a high voltage power corridor, traffic crossings and ultimately a river. The pilot called a few days before we were supposed to go up and said he can’t do it… Fox doesn’t want the liability. Then he called me back a day later and said, what the hell, he’d take me up on his own time. This still seems incredible to me. We did the whole shoot, river and all, and on the flight home I asked the tape operator to rewind the tape so we could check it. He did, but there was nothing there! He had forgotten to press record!! The pilot was so pissed he had veins popping out of his neck. The camera operator had never screwed up a shot in thirteen years of working with this pilot. It was just one of those bizarre flukes. So we get back to the airport, and the van drives up with Joaquin all wet and the other crew and I have to tell them that we didn’t get the shot. Joaquin started laughing because he thought I was joking. None of us could process it actually. The pilot had gone storming off and was throwing trashcans in the hanger. We were all very dejected, especially me because, as I said, without this shot I knew I didn’t have a film. After about ten minutes the pilot came out and very calmly and professionally states it was their mistake, and we would reshoot. I almost started crying I was so relieved. Joaquin couldn’t shoot again just then because he was too exhausted, though in hindsight, a more beleaguered runner might have looked better. We returned a week later for the take you now see. This time, they had to remove a seat in the helicopter so I could fit because in the interim I had been run over by a truck and was in a full plaster leg cast. But that’s a whole other story…

MH: Energy County (14:30 minutes 2003) is a polemic shot in Texas that decries America’s reliance on oil. Highways connect experience, traders bid prices higher, and telephone wires carry ghost voices yodeling for times which never happened. Brown water bays, oil rigs from past and present and a restless consuming fire are collaged with America’s first invasion of Iraq. The biblical undertones of “security” and “defence” (newspeak for invasion, government overthrow and systemic torture) is laid over multiply exposed refineries at night. Christian radio takes aim at an endless enemy, yes, it’s well observed, but aren’t you preaching to the choir here? Don’t the rhetorics of this work ensure that it will find a home on the avant safe circuit, far from the religious right and so help preserve another comforting split between “us” (the good people, who require energy to deliver our good messages), and “them,” the ones busy waging war and pumping oil?

DB: This is a hard video for me to write about because I’ve always felt a little embarrassed by its didacticism and its easy targets. “Preaching,” be it to the choir or otherwise, is something I generally recoil from. I guess the simplest way to qualify its existence is that it served as a release valve for the exasperation I was feeling at our state of national affairs. I made it extremely quickly, a reactionary response to a reactionary situation. My lurching for tractable targets is exactly what the men are doing at the end of the film, burning the flag. Or what the cop (you only hear his voice) is doing when he stops me because I have a camera on a bridge, profiling me as a terrorist. I think the video fails in that this is not evident, but I did want to include and implicate myself in this tendency towards angry dumbness. It’s my car after all that’s being pumped with gas. And the buzz of those electric trees sounds an awful lot like the buzz of my editing drive.

I think the best thing that came out of this piece was the work I’ve been currently up to. It’s hard to qualify yet, but in general, it’s about the culture of elevated threat. And just what exactly it is that this word Freedom represents to people. I’ve broadened my field of Americans I’m speaking and listening to. Whether this will ultimately free the film from being stuck in the “avant safe” circuit seems doubtful. Because I have no interest in making a conventional documentary, and my aesthetic bag of tricks remains more or less the same as its been for the last twenty years. Which means that the venues available to me will inevitably be art houses and festivals and alternative euro channels and experimental film classrooms. BUT, and this is very important, I think when I show the film to the people actually IN it: machine gun owners, Federal Border agents, retirees in their fully loaded RVs, high school football fans… these people will all say, “Yeah, that’s what freedom means to me.” So while I personally might be suspect of how much we have lost or surrendered in the name of “freedom,” I hope that opinion will lurk more patiently in the background.

In terms of what experimental film can achieve in a political world, there’s a passage I really love from Alain Badiou’s essay What is a Poem? “Dianoia* (*discursive thought, or argument and reason as opposed to intuition) is the thought that traverses, the thought that links and deduces. The poem itself is affirmation and delectation—it does not traverse, it dwells on the threshold. The poem is not a rule-bound crossing, but rather an offering, a lawless proposition. […] Philosophy cannot begin, and cannot seize the Real of politics, unless it substitutes the authority of the matheme for that of the poem.” Or as Charles Bowden puts it, “What is explained can be denied, but what is felt cannot be forgotten.”

Ultimately, my frustration with the monologue inherent to the cinematic contract resulted in pursuing other kinds of artmaking alongside my filmmaking. Film demands a mute viewer; someone signing on to leave her own temporal space in order to enter mine. I both love and struggle with the totalitarianism behind this fact. So my non-film work tends to be encountered by accident, requiring participation or collaboration to be activated, approaching something closer to a dialogue. It is publicly situated work that doesn’t rely on the expectation of the sublime, as one would have upon entering a museum, or a movie theater. The nature of the encounter is more democratic. I’m not sure that film viewing can ever be political in the same way.

MH: Kings of the Sky (68 minutes 2004) is an ethnographic document where you find faraway moments with your small digital camera and bring them home. You are in Chinese Turkestan, watching a circus troupe prep and put on a show. Nearly wordless, the camera draws up a series of painterly compositions (shadows on a wall, luxuriant fabrics, candle light) but doesn’t the absence of a speaking subject render these performers as figments of a mute spectacle? Except for Adil Hoxur of course, the tight rope walker, “king of the sky,” whose repeated presentation ensures that the perilous journey of identification is underway. He is the only one whose talk merits titles. Horribly, one of the high wire girls falls off the rope and the crowd is sent home early. The girl (how could she be so young?) survives and a chicken is slaughtered to make amends.

There are travels to two further cities, and two further performances, which lend structure to this “three act” movie. In a lonely night trek, when the movie is nearly done, a lengthy speech details the troupe’s Turkic Muslim background, and its repression (and in turn the repression of all Turkic values throughout China). Thousands of books have been banned, its religions outlawed. First we watch, and then we listen. This is an unusual structure for a documentary, can you talk about your decision to include this information so late in the time line? How did you connect with these folks and what was it like spending four months on tour? How did they view your project, and was it difficult to obtain permission to shoot?

DB: If we gain nothing from experimental film, I hope at the very least it convinces us that there are more ways to ‘speak’ than with words. In my films, I’ve tried again and again to attempt a cinema where strongly held beliefs, political sentiment, existential longing, even historical reverie might be presented and argued non-linguistically. We communicate in so many ways. Why always this deference to spoken language as the more true, or expedient?

You propose that the absence of a speaking subject renders the film’s protagonists members of a mute spectacle. To me they are no more mute than any of us are when we visit a culture whose language we don’t share. Communication still happens. Humor still happens. Concern and gossip and judgment still happen. The First Watch Then Listen format you rightly bring up is something I came to very deliberately after agonizing over structure for a long time. I arrived there for a few reasons.

First, it was important that the film reflect the linguistic muteness of my experience with the troupe. I had no translator, and was just barely able to speak in a rudimentary mix of Chinese and Uyhgur. And yet I had little trouble understanding most things. My experience was made easier of course in that I was traveling with a group of artist-performers who are very comfortable using their bodies to ‘speak’ with. They make their living this way! To me, it seemed absolutely in line with our mutual identity as artists to allow embodied, visual communication to prevail.

Second, language is incredibly politically charged in this region. How you identify yourself (Uyghur or Chinese), what you call where you live (East Turkestan or Xinjiang), what language you choose to speak, and in whose company you speak—all of these decisions are dangerously loaded and potentially criminalized. The atmosphere of cultural repression is extraordinarily sharp and ubiquitous. No one, ever, speaks their mind directly. Everything is couched in double meanings. Setting your clock to local time as opposed to official Beijing time (which is five time zones away) is an act of cultural defiance. Fables are analogues for current socio-political strife. All this is to say that neither I, nor the troupe, was comfortable addressing political concerns directly on camera. Even off camera, they were extremely cautious. Because I did not want to endanger any of the troupe members, and because I was never able to get a Uyghur to actually speak his political mind on camera until I was safely out of the country, I felt that the language of protest needed to come at the end of the film.

Lastly, and maybe this is the deepest held reason for watching first, then listening, I did not want this film to start off dogmatically stating its position. Most viewers have no idea who or what Uyghurs are. I felt that by first revealing their environment, the cadence of their home life, their markets, their off-hours, their music, their architecture, their national sport (tightrope walking) a viewer might begin to have a sense of who these people ARE, before attempting to understand their political situation. We are much more than just our politics. If I started the film from a position of critique, I thought it would shut down the viewer’s experience of Uyghurs as a people with an extraordinarily rich culture and history, not reducible to an ‘oppressed minority.’

I’m glad the film registered for you as two or three performances, as that’s what I was going for with the edit. But those performances are actually cobbled together from over fifty shows, in as many cities, over a period of three and a half months.

I left for Xinjiang with no contacts beyond an English professor at the University in Urumqi. I knew I wanted to make a film about tightrope walkers because the sport seemed to be such a perfect metaphor for the balancing act that is the Uyghur political/economic situation. I was also interested in the region because it’s the most inland place in the world and yet has such a dense history of traversal, being situated along the silk road, and at the monstrous continental joint of the Middle East, Europe and Asia.

I figured if nothing else I would make a film about looking for tightrope walkers. Unbelievably, within two weeks of arriving, I followed a circuitous route via a professor, and then a very enthusiastic and well connected newspaper reporter, the troupe’s manager, a Uyghur psychic spoon-bending Mafioso figure named Kurbanjan and ultimately, Adil Hoxur, the tightrope superstar. I found myself accompanying his troupe on a tour that circumnavigated the Taklamakan desert over a period of nearly four months. It was, in short, a crazy coincidence of generosity and luck.

There’s so much more to say about this film, but I’m going to leave it there. It’s better to watch than read about anyway.

MH: It Will Die Out In The Mind (4 minutes 2006) opens with a rocket flare and then a series of shimmering titles appear as movie talk transcription and interrogation, and an unlikely nostalgia for the Middle Ages. “There’s no Bermuda Triangle. We have triangle A B C which is equal to triangle A1 B1 C1. Do you sense the terrible boredom of this? It was interesting to live in the Middle Ages. Every house had a goblin, each church had a God. People were young. Now every 4th person’s elderly. It’s boring, my dear.” Then a white suited man with a propulsion pack lifts off in the desert (in super-8, slowed down), sending him beyond the crowd, and then back to earth. Yes, I remember when the future was going to look like this, with those strong jawed men leading the way. Where did you find this footage and why use it here, as the closing refrain of an argument? You are making an argument, aren’t you? Where do the titles come from, and why the five hundred year itch for goblins, churches, Gods and triangles with more than three sides?

DB: I like the notion of transcription as interrogation. That the simple act of inscription implies judgment. I guess that’s what happens when histories get written down, epochs get named and ordered, moralized and quantified. I’m absolutely interested in the power of the word, though I don’t trust it.

For me, the film is an inquisition of science by the paranormal. It wonders whether the semantic, while it tramples everything in its wake these days, might not be missing a lot of the picture. The nostalgia is perhaps more for phantasmas than the Middle Ages per se. But yes, I am making an argument: For the possibility of spiritual existence in our information age. For something more expansive and less explicable than logic or technology as the conceptual pillar of the human spirit. For never getting to the bottom of things. The video is actually one third of what I’ve begun to think of as “The Paranormal Trilogy” (How Among the Frozen Words, It Will Die Out in the Mind and The Magician’s House).

Everything in this video is borrowed. There is no original footage or words. All the on-screen texts are lifted directly from subtitles in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker. The high contrast imagery is residual surrounding information from whatever was behind the subtitles. There is one other high contrast image of a miniature model city being hit by a meteor. You see a quick flash of buildings followed by the bloom of an explosion. This shot and the rocket flare at the beginning of the video came from a documentary about meteors that I checked out from the library. I’m embarrassed to say that I can’t remember where I got the jet pack footage. But to me, those scenes with the levitating man and their nostalgia for the future are important because they leaven the nostalgia for the past of Tarkovsky’s text.

The title of the film comes from a passage in Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed:

Stavrogin: …in the Apocalypse the angel swears that there’ll be no more time.

Kirillov: I know. It’s quite true, it’s said very clearly and exactly. When the whole of man has achieved happiness, there won’t be any time, because it won’t be needed. It’s perfectly true.

Stavrogin: Where will they put it then?

Kirillov: They won’t put it anywhere. Time isn’t a thing, it’s an idea. It’ll die out in the mind.

As for the five-hundred year itch, I guess it’s because Western Capital hasn’t allowed much room for autonomous goblins. The mega-church gods serve commerce, and all the triangles with more than three sides are stuck serving the military industrial complex. Maybe they always did. I just like proposing, or no, hoping, that something powerful or romantic or sublime still lurks beneath it all. Not necessarily as a thing, but as an idea, as fugitive as our minds.

MH: Exterior views of a country house with barely heard child whispers and a lonely piano opens The Magician’s House (6 minutes 2007). We see a mailbox announcing that we are in Ithaca, a view looking out from the house, as if the house could look, a shed siding a forest of a backyard. It takes time to make an approach, to enter, and you allow us this time. An emptied chair rocks as an airplane goes by (on the soundtrack) and an organ tries a few notes. The chair grows more animated as the shot goes on (are you playing this in reverse?) A sunset photograph by a window (as if to remind the window of the view) brings us to the mysterious closing shot: a spot of trampled grass, a mark, a sign left behind. You never show us a person (oh wait, there was a photographic portrait in a book, glimpsed upside down), but no one alive and moving, though everything here feels animated. Can you talk about the impetus for this visitation, the very carefully structured soundtrack, the emptied portrait vessel of the house? (by the way I love this movie, it is really fantastic)

DB: Last night I was watching a print of Agnes Varda’s film Cleo From 5 to 7. In it, there’s a scene where Cleo sings about being lonely and feeling like a house full of empty rooms. It happens at her moment of transition from being a fetishized feminine spectacle to more of a participant-observer. I found myself moved by the song, and that line in particular. I’ve always been sweet on filmmakers who let physical spaces be avatars for psychic spaces. Tsai Ming Liang is a genius in this regard and Tarkovskii of course. Too many filmmakers to start listing really. The Magician’s House is my little homage to those films. It lets the house, both its interior and exterior, be a topographic map of a mood. And in this case, my mood was sad, a bit spooked, reverent, adrift.

Why this particular house is a bit more complicated. A filmmaker friend of mine used to live there. He is someone who always struck me as alchemical in his practice. In fact, he’s never seemed quite of our century. I was invited there as part of a small film tour I was on, but by the time I arrived, there had been a stunning series of emotional, physical and professional cataclysms in his life. And so he was no longer in the house. He had quite literally fled.

So there I was, feeling a bit forlorn anyway thanks to my own (unrelated) relationship woes, walking around this evacuated farmhouse, acutely aware of the tangible presence it seemed to harbor. Not necessarily of this missing friend per se, but rather a more ambiguous energy—something that had been until moments before furiously, absolutely filling the place. It was a strange experience. I decided that next morning to shoot two rolls of film, limiting myself to the house and its yard, and I used virtually every image I shot. By far the best shooting ratio I’ve ever managed. It wasn’t until months later that I recorded another friend walking through an entirely different house at night. His are the footsteps you hear in the film. In terms of sound design, in never takes much to suggest a universe. Like Bresson says, the whistle of a train imprints upon us the whole station.

The piano music was an odd coincidence. I fell in love with Georges Gurdjieff and Thomas de Hartman’s deceptively simple piano pieces a few months ago. Gurdjieff himself was a mystic who thought that people wandered around like sleepwalkers, never seeing reality. He composed music to be used as a kind of backdrop for a series of dances he devised to help people be alert to the present moment. I generally hate using entire pieces of music, but decided to use this particular song because I felt the mood suited the house and the film. I only later learned that the title of the song translated as The Struggle of the Magicians. This blew my mind, as I’d already arrived at the film’s title.

The upside-down portrait is actually the face of Athanasius Kircher, an amazing 17th century figure who is credited, among myriad other things, with inventing the Sorcerer’s Lamp, or Magic Lantern—one of the very first cinematic devices. His portrait was printed onto a sheet of plastic taped to the window. There was a little magnifying glass in the room through which I shot the image. For me, Kircher and the fleeting image you see of a projector’s illuminated sprocket wheel become quiet sentinels to the passing epoch of plastic film.

Oh, and yes, I optically printed the rocking chair in reverse. A la Cocteau.

Originally published in: Amerikan Dreamers (2008), and Millennium Film Journal (Fall/Winter 2008).

Deborah Stratman introduction

Deborah Stratman introduction (Sackville, September 17, 2010)

Deborah Stratman is an American filmmaker currently teaching and making work at a great rate in Chicago. Four movies this past year and counting. Not that we need to count. She went to film school in the early 90s and did what many students did, she shook hands with her new medium, she got to know what it looked like, what it was capable of. And then she went on the road for five years, to Iceland, Denmark and Russia, and when she got back in 1999 she made The Boulevard, an hour long video documentary about street racers in Chicago, a mostly late night, nearly all black scene.

Her roots are in the avant-garde film community in the United States, which can mean spending a long time looking at light falling out of windows, but in her hands it means formal rigour and social engagement. A rare mix as it’s turned out, and one that she’s struggled to pull off herself. It’s so much easier to come down on one side or the other, to cozy into the formalist light shows, or to enact the familiar television diction of the social justice documentary.

Energy County (14:30 minutes 2003) is a lyrical documentary short made in Texas that decries America’s reliance on oil. Ghost voices yodel for an excellent past which never happened. Water bays filled with sludge, oil rigs from past and present and a restless consuming fire are collaged with America’s first invasion of Iraq. Biblical undertones of “security” and “defence” (newspeak for invasion, government overthrow and systemic torture) are laid over multiply exposed refineries at night, as Christian radio takes aim at an endless enemy.

In 2004 she spent four months with a legendary tight rope walker in Chinese Turkestan, and made the feature length Kings of the Sky. An open form video doc that showed an intimate spectacle, and a Turkish Muslim community looking for a place where they could practice their religion without persecution.

Along the way there were found footage studies, homages to scientists, lyrical expressions.

She has also been busy as an artist, working in art galleries, or in the expanded field, far outside the confines of the movie theatre.

In her Evacuation Routes project she took out classified ads in Houston newspapers that invited viewers to send her maps of escape routes in case of hurricanes or other natural disasters.

This is what she wrote about her 2004 project FEAR. “I distributed printed cards in 30 public phone booths around Chicago. The cards had a toll free number printed on one side and the message “The more you desire safety, the more there is to fear. Call now,” printed on the other. When a person called the number, they heard the following message: “At the tone, please describe what you are most afraid of. If you need time to think about what you are most afraid of, hang up, think about it and call back.”

In 2002 she made her defining work. My friend Phil says that most of the movies that he makes, and that most artists make, are like place holders. They’re not the genius thing, the perfect moment, they’re signposts along the way. This is as far as I got this time. This exploration, this sideline, this digression. When you go to a movie festival, any movie festival at all, you realize right away that we’re not all born like Mozart or Marguerite Duras.

Before tonight’s movie, which I think is her culminating masterpiece, her shining moment was a half hour film called In Order Not To Be Here (33 minutes 2002). Mostly shot at night, it opens with a police arrest, and closes with a long shot of a man appearing to run from a crime scene. We see the fragile compact of home, walled up, fortified, dogs baying at night. We don’t know who you are, but stay away from our overstocked kitchens, our garages bursting with cars, the booty lining our closets. Every empty street hums with menace. Here is the crime scene without the crime, a stalker movie without the stalker. A defining moment for her as an artist.

Which brings us to tonight’s screening of O’er The Land. It was made last year, it’s 52 minutes long and features the same kind of experimental documentary mosaic style, and careful shooting on 16mm film, as In Order Not To Be Here.

In all of her work I can feel this tug, this pull and necessary tension between the thing that’s happening over there, in front of the camera, and the thing that’s happening over here, behind it. Because every time an artist sets up a camera they are taking a position. It is a viewpoint that is also an ethical statement. This is where I stand, this is what I stand for, and this is the record of my stance. This is particularly instructive today when cell phones and cheap digital cameras have produced an avalanche of video made by people who don’t know how to look with their digital extensions. They are pointing their cameras vaguely towards… something, but they don’t know how to find a picture there. In Deborah’s hands, with the tripod’s three legs placed securely on the ground, the filmmaker produces a collection of vantages, frame after frame, from which we can see the scenes presented to us, but we can also see the way she has decided to show them to us. We look over her shoulder, in order to see how an artist looks through time.

I’d like to invite you to see the way she often pulls herself away from the centre. In fact, this movie is very concerned with questions of what belongs in the centre, what is usually at the centre, the centre of power, the centre of attention. Over and over again, Deborah finds that centre and then pulls her camera, her view, away from that place. She empties out the centre, and in that newly created space she gives us time to think. This is a motion picture essay, inviting its audience to piece together this constellation of lookings that turn around an emptied centre. And in this space that doesn’t try to fill me up, that is not propaganda or audio visual slogans, I am granted, as a viewer, a freedom to choose, to decide for myself. The filmmaker wants to produce a model, or a picture of a rarely felt freedom and she wants to do it right here, tonight, in this place. Because the radical democracy she longs for is all about you. And your response, and what you feel, and how you’re going to put together the pieces she’s presenting according to the inclinations and gravities of your own life. Everyone with their own version, each according to their need.

O’er the Land by Deborah Stratman

51:40 minutes, 2009

Fear of Flying

My Czech avatar Andrea, a friend to clouds wherever they might appear, urges me always to take a window seat whenever I’m off the ground, so that I might be able to examine once again the necessary atmospheric cover, so close I can nearly touch it, lying like wayward tufts of child’s candy. But while I thrill to look at clouds from both sides now, I never take the recommended seat, because when I look down I can see stretched before me a shrunken city of lights, a miniaturized movie set with dollhouses and toy cars and invisible strings tugging at it all. The airplane grants me an “overview.” I am riding, along with my fellow passengers, “above it all,” and perhaps it’s all those Vietnam newsreels I watched as a child, but I can’t help feeling that this view is some necessary preamble to destruction. It is not only the ability to kill at a distance, which the airplane offers as an extension of the gun, but those humans are so far away from the smilers that offer me snacks and entertainment devices, that it’s difficult to regard them as comrades. Those tiny coloured dots in the landscape are only design elements now, and no longer parents and children, ailing mothers and teenagers hoping to fall in love. After lift off ‘they’ have become faraway abstracts that can be stepped on, gassed, strafed, and bombed. Call it the royal view. The friendly skies.

Central Character

The main character in Deborah Stratman’s O’er the Land (52 minutes 2009) is never seen, though he speaks almost obsessively about his body. Yesterday, at Hartley’s fourth birthday party, I met a Frenchman who scratched himself continually as he spoke. It was as if his restless fingers needed to remind him: you live here, this is your body.

Stratman offers us Colonel William Rankin, a US airforce pilot, forced to eject from his fighter jet while running errands over America in 1959. He leaves his plane 48,000 feet in the air, and promptly gets caught in a massive thunderstorm for nearly an hour. He is frozen, burned, flattened and broken. No longer above it all, he is propelled into his very own contact narrative, just another part of the natural world. But unlike the singsong nature happiness strung up in rhyming verse by the Romantics, the natural world Rankin encounters is harsh, overwhelming and entirely indifferent. To risk stating the obvious: he doesn’t belong here. And what is most surprising, apart from his sheer survival, is the fact that this extreme threshold experience never budges the speaker, it doesn’t make any real impact on him at all. Perhaps it is because his rigorous military training allowed him to disengage from traditional panic buttons, but it’s strange to hear him speak of his encounter, and in such exquisite, storytelling detail, as if he was reading someone else’s newspaper account. Not for him the credo: biology is biography. Instead, he has turned his body into a fighter jet, and converted the natural world into a set of conditions which can be calculated and overcome. Even when he’s in the midst of his own death, he’s still working out the math, the subtle geometries of descent, the probabilities of system failure. He appears to himself as a tiny coloured dot on the landscape, far away from his own frozen, shattered husk of self. How else could nature be encountered by this faraway body, except as an ordeal to be endured, a set of distracting circumstances that might impede the functioning of this meat instrument?

Re-creation

Each year, thousands of men (and a few women) take part in costumed war re-enactments sponsored by groups with names like Panzer Grenadier Regiment (UK), Medieval Rose (Greece) or The Brigade of the American Revolution (US). Full regalia includes painstakingly replicated guns, swords, muskets, spears, tanks, maces, tomahawks, canons and more. Drills and rehearsals are run “in full kit,” members solicited, ranks assigned. It’s déjà mort all over again. Is it the lost pleasure of predictable outcomes they are looking for, a child’s delight in becoming someone else, or war by other means?

In O’er the Land, Stratman lenses a reenactment of The French and Indian Wars, an 18th century bloodfest that saw English troops vying for North American control. Although “successful” (ie. more French soldiers than English were killed, followed in short order by Native massacres (their punishment for choosing the wrong side), the bankrupt English treasury laid extra taxes on their colonies to make up the deficit, which led in part to the breakaway American revolution a decade later.

Stratman plants her camera in bucolic natural surroundings, and favours wide shots that lend equal weight to background and foreground. She shoots these weekend soldiers “in the back,” from behind almost-enemy lines. This not-quite-embedded reporter finds a reaction shot in the seated child scrums that gaze distractedly at their tarted up dads strolling across the green with muskets raised and ready. Here, colonial expansion returns as family entertainment, where the unsteady columns resemble nothing so much as halftime shows – part spectacle, part home movie boast – the clumsy mathematics of bodies ironically working to erase any trace of death or dying. But wait. Perhaps they are not performing an act of memory, or even grieving, but enacting a pantomime of past traumas. How did Marx put it? Everything in history appears twice, the first time as tragedy the second as farce. Enter the reenactment. The sanitized battlefield quotation. Or is it darker than that, dad? Perhaps the persistence of long ago traumas includes spectaculars of disassociation like these, featuring the compulsive need to act out, to recall physical sensations of generations past, as if nations, too, might be haunted by their unconscious, forced to repeat their trauma-struck fixations.

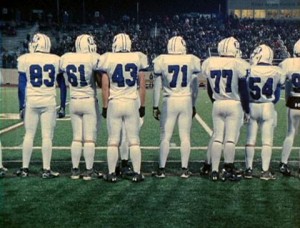

Sidelines

From the battleground Stratman delivers us to the football field, a sport that measures territory in gains and losses. The aim is ball control, possession, contained violence, maximum impact, and above all, as Stratman shows us – marooned once again on the sidelines, where the real action is – the rubbing together of male bodies. This is how we come together, as men, this is what groups of men create. Geography as a sign of power. The “land” is marked and gridded for easy reading, the billiard-table-smooth artificial turf laid over unnatural ground. The players appear as parodies of masculinity with their outsized shoulders and spiked shoes, ready to “pay the price” for every precious bit of real estate. But the drama of pulled tackles and perfect spirals is not the lure here, instead, the filmmaker serves up end zone cheerleaders and sidelined brass bands. The game itself is a distant afterthought, strictly backdrop material for the identity/behaviour vectors that are busy forming in its wake.

RV Park

There is no voice to guide us in the filmmaker’s darkness, no easy line of words to follow as we are asked to make the jump from one scene into the next. From the football field we are hotwired into an RV park at night, the gathered parking lot of home filled to bursting with one mobile promise after another. These car homes appear as specimens from a forgotten zoology manual, and I am filled with questions like: how does she manage to film these vehicles as if she’s never spent a day on earth? How does she impart a necessary distance so that we are able to see them not as the temporary stage for our own restless hopes, but as if we are looking forward in time from a moment when these fabulations were not yet conceived? We, the audience, the mute spectators, are asked to see through the eyes of the ground itself, the kilometers of worn road, call it landscape if you must. But it is animate here, a moving presence amongst these toy houses on wheels, with their miniaturized suburbias, their calculated innoculations against experiencing anything at all. The armour that still passes for the good life. Painless and numbly faraway.

Women

There are not a lot of women who wander out in front of the filmmaker’s maternal stare. Instead, this essay demonstrates a world bricked up by men, only they can’t seem to get the proportions right. Everything appears too large or too small. Everything is a tool or a machine or a game, in other words, extensions of the sandbox. And all the men appear in costumes barely graduated from Halloween. It’s kid town, it’s hide and go seek with nuclear weapons, it’s cops and robbers with border trackers and firemen. Stratman leans on wide shots filled with scape which make these boy-men appear as frontier clowns, lapsing for moments into accidental rapture as a group of amateur flame throwers, before returning to an aimless rage in the father-sun submachine gunning of a designated car target.

Perhaps saying frontier clowns is too much. There is still something friendly, almost accepting, in the way that the filmmaker looks at her charge, almost forgiven. As if they can’t help themselves from doing that, again and again. Somehow her looking has a mother’s touch, which lends a necessary ambiguity to this project. She dodges the polemical screed, the one-sided vanishing point of an argument, by insisting on not-knowing, on some suspension of judgment, which she offers her viewers as a gift.

And yet. Everywhere she looks I can see the drive towards abstraction. The scientific faith, the blindness that impels progress, and the deeply infantilizing succour of rationality. This is an America that has never grown up. That refuses to grow up. Experience, as Colonel Rankin makes clear in his post-self memoir, is no teacher, it only gets in the way of the Idea, the mission, the code; or whatever is being laid over the present to keep it from happening. Above all don’t make me feel. I’m OK, You’re OK. The kids are alright. Let’s keep the ball moving forward, a rolling stone gathers no nuclear dust, and that smoking gun doesn’t belong to me, it just walked over and put itself in my hand. It’s not my war and he’s not my president. It wasn’t me, officer.

Take, eat, this is my empire

Everywhere in O’er the Land, America’s cherished certainties have frozen into childhood idylls which might be charmed sideshows if they were not the symptoms of an imperial culture – grounded in genocide, raised on a messianic myopia, and determined to kill anyone who gets in the way of a global Lebensraum. It began with the Native population, who were nearly slaughtered down to the last woman and child, and then the home of the braves ran south, plundering the waning Spanish empire, land grabbing from their Mexican neighbour, setting up concentration camps in the Philippines and military dictators in Cuba, Guatemala, Iran, El Salvador, Chile, Nicaragua, Vietnam… All in a day’s work. How does all that killing look at home? Like a whole bunch of Mcdad’s at the Machine Gun Festival, perhaps, sharing with their first borns the joys of a simulated kill. Or the Viet Cong re-enactors who wait for the filmmaker to give them direction. What part do I play? What do I do next? There are enough corporate media outlets offering ice cream castles in the air to keep these imperial eyes wide shut, ignorant of America’s secret torture prisons, the White House hit squads, the extraordinary renditions, the Christian mercenaries in the Holy Land, the endless sabotage of the Palestinians, the drone massacres in Yemen and Pakistan. Neo-liberal capitalism turns out to be war by another name, and there are few enough in the self-named “avant-garde” of American movies who have been willing to say anything about it at all. No doubt, they have more important things to do.

The Illinois Parable by Deborah Stratman 60 minutes 2016

This hour-long essay doc by premiere experimentalist Deb Stratman offers her episodic take on the American imperium as it stretches out to occupy its own newly expanded borders. Her keen landscape eyewitness are framed in a suite of eleven marked chapters, each of which carries a parable, a word with Latin roots meaning “comparison,” a simple story that aims to distil complex truths in an accessible form. The movie’s opening aerial view seems to offer us a divide between a teeming city and the cropped geometry of farmlands that lay beyond its borders, though in both instances the land is subject to overdevelopment.

The question of the land — land as territory and identity — is never far from the filmer’s lens. The earliest scenes offer us pictures of indigenous peoples, from the singing of shaman Raven Wolf, to the dioramas of a people immersed in a landscape that has not yet been named Illinois. President Jackson orders federal troops to march thousands of natives off their land following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and many die terrible deaths of exposure and starvation along a route named The Trail of Tears. Stratman shoots the Trail across the seasons, as a reminder that the walk was not a sunny frolic but a slow and deadly trudge. In a later scene, revellers slide down snow hills, squealing in delight, families gathering in the white mist. The camera is perched behind branches heavy with snow, as if a lingering indigenous presence looked on, waiting for the white people to leave the place they used to call home.

A rich and sensitive score by Chicago-based composer Olivia Block provides a stirring counterpoint and accompaniment, sometimes with spare piano notes, sometimes resonant percussive tones or thick drones.

From the expulsion of the Mormons, to the infiltration and state assassinations of Black Panthers like Fred Hampton, self-governing communities expressing their own beliefs were systematically plotted against and destroyed. A vicious tornado topples buildings and kills hundreds, mysterious fires ravage neighbourhoods, and it is difficult not to see both of these as an allegory for the government itself, which leaves a ruin in its wake. The abstractions of science provide a cover story for this ongoing colonialism, math equations lead to the state’s nuclear experiments. The history of Illinois, the filmer suggests, is a history of intense state pressure brought against its dissident populations. Don’t miss this state of the disunion address by one of the most urgent voices working in fringe media today.