I Was Tired of the Super-8 Ghetto: an interview with Steff Ulbrich

Steff Ulbrich is a multi-disciplinary artist living and working in Berlin. His performances, still photography and artist’s books led him eventually to the cinema. While most of his work has been in super-8 he has recently begun to reconsider the economy of super-8 production/distribution/exhibition and has begun making work in 16mm. His films combine a resolutely personal expression with a frank and open imaging of sexuality. He is married with two children and badly in need of money to make his next film.

MH: What do you they call your work here: experimental, avant-garde, underground?

SU: There’s no real word for the work my friends and I are making because a name always comes after, not before something. So you can it “experimental” but it’s a special kind of experimental.

MH: What makes it different?

SU: Films were experimental in 1968 but no longer. W use the experience of structuralism and we know about the formal avant-garde but we use as well a dramatic structure in our films – there’s a balance.

MH: Are there other common themes?

SU: One theme everyone has in common is sexuality.

MH: Last night I watched Kali Film by Birgit and Wilhelm Hein – an “experimental” German film about sexuality. Are the films you’re describing like that?

SU: No, the Heins belong to the older generation (1968) and they’re really good at selling themselves, everyone knows them. But I can’t see that they’ve found anything new for themselves over the last ten years. It’s not bad work but they ignored all their structural filmmaking, and tried to make something else. So they couldn’t be really sincere in making their structural films or their drama films either. They’re just trying to keep in fashion.

MH: How did you come to filmmaking?

SU: Structuralism influenced me much but because I lived in a small village I could only read about it. Then I went to Cologne and met Birgit and Wilhelm Hein. I stayed there for three years and saw a lot of these films. Some are not worth seeing, some are just good ideas, lectures, bringing some philosophy to a point. Structuralism has no place for emotions, so it can’t survive, it’s just a very intellectual thing.

MH: Did you start making films in Cologne?

SU: No, I started after reading about structuralism. I also tried to make these films but it wasn’t really satisfying.

MH: Did that change after you were able to see a lot of that work in Cologne?

SU: Mostly, I studied art and made performances. One was called Altar. I documented my way of living, making photos and collecting objects from my room. I contacted Daniel Spoerri and Joseph Beuys and tried to make contact with Kristl and asked them to take part in this Altar performance. I didn’t tell them what to do – they just looked at the photos and Beuys wrote something on them – things like that. In the end I destroyed it by publishing it all, piece by piece. I put all of the objects and photo negatives in a self-published magazine, in each a different set of pictures, so in the end I had nothing left.

MH: In your film work was there a shift from structural interests to more personal work?

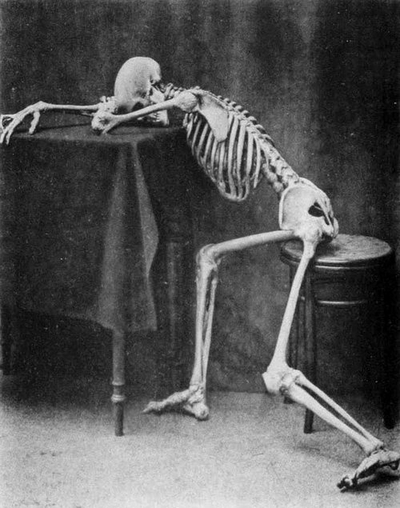

SU: Yes, I made two short films called Self Portrait which are both personal and structural. The first was made in 1980 showing a Polaroid coming out of the camera and developing and after a while you could see me filming the camera. (laughs) To show me as a filmmaker. (laughs) The second showed me posing – re-dressing, naked and posing, all cut quickly in-camera. Then for a while I gave up filmmaking because nobody is really a filmmaker or painter or writer, most people do everything, and for me there were times when I was writing a lot of making photographs or making performances. But when I came to Berlin, in 1982, I made a different kind of art, something between land art and performance. I made photos of victims. I lay on the ground in bars, on the street, on the pavement and had someone chalk a line around me, and cars had to stop when I laid on the street. I went to the Orange Bar. It’s a homo bar, quite famous, and I laid on the ground and people thought, “What’s with him, he’s drunk,” and someone was with me and made the chalk outline but then someone came and laid on me and kissed me. (laughs) It was my kind of experience with cities because I was in many cities at that time, I was in Cologne, Berlin and everywhere in Germany I made this performance.

MH: Would you leave the photos where you took them?

SU: I just took them, I wasn’t very interested in being famous. In this period I made no films at all. Then I wrote a treatment for a film and received money in 1986. It’s called VerFilmt in Germany and Shot in America. This is my first long film, 45 minutes. All the other films are between 1-4 minutes and they’re all super-8. This one is 16mm. I’ve also made a video that’s quite long, 3 hours. It’s a good example of this structuralism coming together with drama because it’s called Video For Living, and all you can see on the screen is an aquarium, but in the background you can hear a drama going on, a very slow spare drama, in normal time. I showed it to Birgit Hein and she said, “Oh, it’s really shit,” and after that I didn’t dare show it to anybody. It’s never shown anywhere.

MH: Can you talk about Shot? Was that the first film you scripted?

SU: I’ve finished ten scripts but made just one because I don’t have the money. Dramatic films in 16mm cost but I was tired of the super-8 ghetto. Super-8 films are made for other filmmakers, you can’t get a real audience.

MH: Others have reported a big boom in super-8 around 1980. How was it different then?

SU: Well, it was a little big boom. At the moment only one theatre in Berlin shows super-8 films, and then perhaps once or twice a month, Kino Eiszeit. Arsenal shows super-8 maybe once a year. In 1980 a lot of people came to make super-8 and they didn’t know anything about film so they made films like the 1968 16mm films. Only a few tried to find their own way of making film. But the others were all doing what was done before, and after awhile this became obvious to them, to everybody, and they gave up filmmaking. They sell their camera to someone who does just the same, reinvents films without knowing what’s gone on before. Only a few try to make something new in light of the history. I think that’s important. If you go to a super-8 festival you see a lot of bullshit. It’s a malady, an illness of super-8. Many people think it’s really cheap so we can have cheap ideas. Most of the few who have ideas are also making 16mm films. Like Michael Brynntrup for instance, or Derek Jarman. In this 16mm films I made I used bits of super-8, it just depended on what I needed.

MH: What is Shot about?

SU: It’s about me. It has a lot to do with masturbation and thinking about film and thinking about me, not in a solipsistic way but in a philosophical way. It’s a very autistic and narcissistic film. I’m actor, cameraman, editor, and this kind of filmmaking is typical for the film because it’s going in circles around me. It’s a comedy really but nobody in Germany understands this. Mostly foreigners see it this way.

MH: How does it progress?

SU: It’s made on two lines. One is made in black and white. It’s a story set in a blood bank which turns into a café. There’s a woman, a nurse, who takes this man’s blood and he falls in love with her and you hear tango music. A waiter comes and brings wine but he can’t open it. It’s hard to talk about, I don’t want to make a mathematical film but I think about mathematics when I made a film – about how things add up. There’s one part in Shot just 3.5 minutes long and there’s 300 cuts. First I had an idea of what I could make because this sequence was more like music, you could see foreground events while in the back there was a screen which showed the foreground moving in an endless loop. This loop was cut in a special rhythm, so I cut the scene to that rhythm. I had all these work prints and I cut them into pieces and laid them on the floor for days like a puzzle. What I didn’t know is that I couldn’t afford to make the negative cut so I had to make a copy of the rush prints, with dirt, but it was okay, you should always let reality into the film on many levels. On a material level, for instance.

MH: You have a family. Is there pressure to make another kind of work to make money?

SU: For Shot, I got money to make it, but not to live on. You get money only if you sell to TV. For Shot it’s difficult because it’s about sexuality and not naked tits, it really touches you. It’s really offensive, not with pretty girls but with me. The film is about me and the way my children have changed my relation to sexuality and there is no money in this. If you live alone you live in a very artificial climate and you don’t have to care about some things but in fact in the end you have to care about children. If you don’t have any children in 10-20 years you won’t have anyone left to see your films. (laughs) It’s true. But many artists don’t like children. They think they can’t work. I think it gives you work something – especially when you talk about sexuality, which most filmmakers I know do; they talk about it in an abstract with, with symbols and analogies, but some are trying to talk about it more directly like I am. Structural film is something you do when you’re alone and you’re bored, you play solitaire, it’s just a game to keep you occupied. Before I was just busy being busy. Now with the family I’m really trying to say something, I have no message like propaganda, but I’m more conscious. Shot was very different from what I made before.

MH: Could you talk about the short films?

SU: They sow one idea. They are very compressed things. I made no films for some time, then I made this 16mm film and when I was working on Shot I made about five hours of super-8 material, and I made some short films out of that. They reflect singular ideas in Shot that go in another direction. I had one scene with the children standing in front of the mirror, looking at themselves, and knocking on the mirror, and running around, and leaving the picture and laughing at the camera, and the body running to the camera and holding his hand up to it. I mad this in super-8 and I took another film – Roger Rabbit – so I had this contrast between a home movie and a movie you watch in the home. The super-8 film was a dream sequence because my refilming from the screen changed all the colours. It was the same material but two films came out of that, like the difference between writing something by hand and using a typewriter. The super-8 was handwritten. I’d like to make more films out of this material but it’s so tiny, this super-8, this little world.

MH: But it’s nice that you use super-8 in an almost traditional home movie way, reworking that tradition. Is there a difference in the way you film yourself which you’ve done for some time and the way you film your children? I’m wondering how your kids relate to the camera?

SU: I don’t know… there’s a difference. When I film them it’s mostly with super-8 and I’m very aware of how someone else would shoot them as a home movie and I try t play off this in my work, my shooting.

MH: Can you say something about the images of your life, this parallel life almost, this image world you’re building showing yourself and your children. What is the relationship between this familial world and the life of the family?

SU: Everybody’s work documents his/her life, this is what I’m making explicit. This development I spoke of before is parallel to film development. Shot is a very narcissistic, autistic film. The film I’m making now is really away from me. I’m working with Harry Baer, an early actor with Fassbinder. I think it’s a state of mind I’m coming to, so I had to change my way of making films. It’s always changing. In Shot I took ideas from the films of film history and re-made them. In the new film I took a part of a George Bataille novel, The Blue of the Sky. I wanted to make a long adaptation of this book but you have to buy film rights so I decided to make a film out of this fragment. And a friend of mine gave some money to hire an actor. This film has a lot to do with theatre, with how people stage themselves. The protagonist is lying in bed, it’s filmed in a hospital. In the book he’s visited by a woman and he wants her to sing something. She does and after he says, “It would be nice if you’d sing it naked.” Then she sings it naked and it’s over. What I’m changing is that the woman’s visit isn’t real, it’s just his imagination. It’s an inside drama. All dramas are inside and outside but the problem is they think it’s all outside with action so they don’t use the language of film, they only illustrate the theatre.

MH: About a week ago my traveller’s cheques were stolen and I had to go to the police and tell them the story. It seemed to me then that the law, the word, has to do with those moments where your life becomes a story. There’s an enormous flux of events always, but at a certain point something happens, and everything around that event becomes attached to it, ordered, and given significance.

SU: I think the law is a very high expression of our culture which is basically dramatic, it represents us, and we live in the reality of our representations. Now things are changing. It’s no longer possible to tell stories because of technology. In a book, the information falls in sequence, but on a computer or a newspaper everything happens at once.

MH: What happens after the story? How can you communicate if you can’t tell a story?

SU: A film should build an emotional room in the place of a story, but now there’s still a mix. In a horror film the feeling is the main message, not the story, though it shows both. The computer changes what it means to be personal, I don’t know which is first, the change in culture or technology.

MH: Does this have something to do with changing the form or structure of a film? New technologies also change the shape of our present, so formal change anticipates the way accelerating technologies become less our extensions and more the way we work. This seems to me a good reason to be concerned with formal issues, which seem always to live in a self-contained world oblivious to their surround, and yet which continue to provide an image of changing systems and how it might be possible to live in those systems.

SU: Yes, in a film, for instance, you can show time voyages. In the image world they’re technically possible, because we’re increasingly adept at manipulating time, or the image of time. Then reality may follow. For art the material is very important and if your material is time this is something new. When I was young my father took many photos of me, and I have many pictures in situations I can’t remember. Sometimes I think I remember myself as three or five but then it turns out to b just a photo. I’ve no original remembrance of it. The photographs takes the place of memory.

MH: This is the argument Plato uses in the Phaedrus. He warns against the new technology of writing, claiming it would take the place of our memory.

SU: But you never have an original remembrance of anything. You can’t have your past back, memory is always partial.

MH: But I wonder if it isn’t possible to have a perfect memory of something, to remember everything about one moment, every look and smell and taste. That memory would be no different from being there, it would be like traveling in time. I think film is a little like that, an image of a perfect memory. Schemzdahin’s films are like this, they’re very emotional, hinting at stories without ever telling them. They want to convey the feeling they have while working through the material. The films seem to be the trace of their passage, of their coming together as a group.

SU: Yes, they work on physical materials, like the vanishing shots in Shot. I had a project with a film with a story and I wanted Schmeldahin to develop it but I couldn’t get any money so I couldn’t make it.

MH: Is it hard getting money?

SU: If you need 15 or 20 marks you can afford it. But from the State it’s difficult, especially in Berlin. There’s money for film but not for our experimental work, only dramatic films or these very boring advertising films. I got the money for Shot from North Rhein Westphalia; I couldn’t get it in Berlin.

MH: So do the independent filmmaker spay for their films themselves?

SU: Yes. At the moment we’re trying to create an arts council. Many people are making our kind of film in Berlin but they’re always hindered in their work because they have no money. Now it’s getting to the point where the city council controlled by the Green Party says, “Okay, we’ll give you money.” In Hamburg and North Rhein Westphalia the bureau is self-organized, they elect their own changing juries of filmmakers. But in Berlin they have a jury for ten years now with four bankers and one, Erica Gregor, who is very conservative, and these people make the decision every time. The government doesn’t want to change, but we have to change this because without changing the jury you don’t change anything. The government in Berlin changed half a year ago and I wanted to make this film with Schmelzdahin and I thought why can’t I get any money from Berlin? I called Michael Brynntrup and Michael Krause and said we should do something. So we invited every party and the man in the government who is in charge of film to a round table at the Berlin Film Festival and the government changed to a more liberal party. But now it looks worse than it was before, they call themselves progressive parties, but in cultural matters they’re really conservative. They want only social documentary work, and they have problems with sexual films. It’s because the women’s movement is a part of the party, and parts of the women’s movement thinks that the best kind of sexuality we can have is no sexuality.

Most of the avant-garde filmmakers now are talking about sexuality. It’s very important, and I think it will be for the next ten years, or longer. It has been important since the beginning of film. A regular porno film is framed by the porno theatre and the meaning is only money, the way the images appear. But in a film like Shot it starts from inside so you can’t dismiss it so easily. People don’t want to know about sexuality. Once you start rethinking sexuality, you change everything, not just the sexuality but the economic system. People wouldn’t be so easily manipulated, for example. You have to find new viewpoints and new ways of showing it. It all works together, the filmmaker develops, the audience develops, even film develops as a medium.

MH: I think it’s hard because we never come to the theatre for the first time, we already know what film is and that stops it from changing. I think it’s the reason more people won’t see the work you do, it’s not enough like Hollywood, the future isn’t enough like the past.

SU: Spengler says we can’t understand classical art at all, we think we understand but we just project our own ideas. For instance they had bronze statues in nature and they were very shiny, golden in the sunlight. But when we see them they’re covered in a green patina and we put them in a museum room so they’re really different. It’s not what it was before so we’re condemned to our own time.

Filmography/History*

1960 First time photographed

1975 E=Mc(2) First super-8 with friends

1978-1985 Much super-8 work including: Selbstportrait I, Selbstportrait II, Altar, Winter, Naabbeton, Mullerstrasse. This isn’t the order they were made in, I don’t know myself, these are films I’ve never sent to festivals or show them except to friends. All 1-5 minutes.

1985 Video for Living Room, a video more than 2 hours long. It’s had one showing for one person.

1986 Trailer for Anna- The Chinese Method 4 minutes super-8

1987 verfilmt/Shot 45 minutes 16mm

1987 besonders trocken 5 minutes super-8

1988 Alles Fisch super-8 endless

1988 Shot-Trailer 4 minutes video

1989 Blau/Bleu/Blue 20 minutes 16mm

*Ulbrich notes: “I’m really exhausted and sure that I’ve forgotten some things like my version of expanded cinema in 198? when I declared the whole world being a film.”

Originally published in: Independent Eye Magazine/Germany: Over the Wall (Spring 1990)