Jane: How did you get involved in programming at the Images Festival in 1999?

Mike: Don’t you find that all of the important things in your life happen by accident? I had recently trekked through a series of festivals, and had begun to look at the form of these gatherings, wondering how some motion picture stagings worked so well, while others failed. I was in touch with Karyn Sandlos at the time who was on the Images Board, and together we must have been in conversation with Deirdre Logue. These chitchats led to a proposal manifesto that talked about how movies might be introduced, ideal program lengths, potential demographics. As it turned out everyone was leaving the fest, the house was suddenly empty, so I was invited by the board to apply for a position that might not have existed. I took the hiring to mean simply: let’s begin again. I threw out everything I could get my hands on. The office was heaped high with VHS tapes and DVD screeners and papers filled with hopes and promises. I recycled all of that, then made my way to the storage room in the basement and tossed whatever I could. Desks were emptied, personas unpacked. I could feel the weight of all those years of effort, the enormous tug required to lift this heavy machine year after year. Every couple of weeks Deirdre would come in looking like she hadn’t slept in a thousand years, and she would make a slow motion scan through the remaining papers. I think I was inspired in these efforts by the description genius poet Anne Carson’s offered about her own method.

“I have struggled since the beginning to drive my thought out into the landscape of science and fact where other people converse logically and exchange judgments — but I go blind out there. So writing involves some dashing back and forth between that darkening landscape where facticity is strewn and a windowless room cleared of everything I do not know. It is the clearing that takes time. It is the clearing that is a mystery.” Economy of the Unlost, Anne Carson

What Carson describes as clearing was the first step. And the first step is always the most important. You can make a thousand good decisions, but if they follow a single misstep at the beginning, the project is headed in the wrong direction.

Jane: What were your goals as Artistic Director? You are quoted in Andrew Paterson’s article for the 2012 Images guide saying that the Artistic Director position would move from work being “done by a committee process to being done by someone with a coherent overall vision of the programming.” Also in your conversation with Yann Beauvais, there is a discussion about the festival becoming more like a database or library offering multiple choices rather than presenting a “privileged curatorial point of view.” Can you discuss the significance of this idea when you became AD? Were there any concerns raised about this and, if so, what were the issues?

Mike: Committees are excellent for turning the boat in the right direction, but not so good for bringing it into harbor through rocky waters. My friend David is just back from a pair of German fests in Oberhausen and Osnabruck and lamented their groupthink committee programming. Stardust appeared next to students still struggling with the rudiments of cinema grammar. It raises the uneasy question of taste and responsibility. Who is the festival for, who is the audience, and how could that audience be more diverse? One of the things that’s interesting in your question is the apparent contradiction between the single curatorial point of view and the festival as a library database that admits multiple points of entry. What’s it going to be: the one or the many? And this question begs another: who is it for? Computer programming offers instructions for how a machine can operate. Is a festival program offering instructions for how a community might interact? How a community might become a community?

When the Images Festival began, it enacted the unholy marriage of film and video. That simple act was enough to create a fireworks display that embraced the two solitudes in a new way. The success of the festival over the years might be measured, in part, by the proliferation of other fests, small and large, catering to a bewildering array of micro-communities. Today we no longer need a priest to oversee the film and video marriage, we crossed that threshold, we got over it. So what place did the Images Festival have in this vastly overpopulated Festival landscape? The question that the Festival faced, and continues to face, is the question of too muchness. How to make work in a moment when too much already exists? How to put on a festival in a city where there are already too many festivals? As an artist, I am someone particularly interested in forms, and as the artistic director, I was interested in testing, challenging and reshaping some of the forms that reside within a festival. I imagined the accumulation of those forms as a single picture, and hoped to offer up the festival as a demonstration of what might be possible.

As usual, it was necessary to move in two directions at the same time. I believe that it is vitally important to celebrate local manufacture. There must be portals, and preferably the most esteemed and perfect and most treasured spaces, available for local artists. In previous years the fest had staged a number of “homebrew” programs, which played to packed and enthusiastic audiences. It also meant that other screenings were less well attended. My hope was to extend the homebrew ideal across the rest of the festival. I worked to expand the local content, and broaden the accepted presentation modes to include slide shows, more traditional documentaries and performance. I also worked with Greg Woodbury at Charles Street Video to put together a program of commissioned works, new videos made by local artists who would be able to access Charles Street’s high end video gear, and then premiere the work at the festival. It was an integration of production and exhibition, and provided the spark for a new commissioning program at the Canada Council.

While it is imperative to highlight the very new and very local, it is also important to have roots. Festival culture turns around an endless hankering after what is new. But as someone who has been attending fringe movie screenings since the early eighties, it’s obvious that many dazzling moments played before small audiences and then never showed again. My proposal to the board was that I would roll out some of the finest movies ever made, in part because I was convinced that very few had ever seen them. I wanted to produce a deep background frame in which one could see local manufacture. For instance, I showed a number of shorts by the Armenian genius Pelechian (who had never shown in the city before) not simply because we wanted to cheer a bygone inspiration, but because it was important to rub his collage work from the sixties up against digital mixmasters like Istvan Kantor, Gunilla Josephson and Jubal Brown. The festival tried to create a dialogue between generations, in order to find a way to speak about what is important to make now, and how to make an approach to those makings.

Jane: You have written about attending festivals, presenting your work at festivals and, of course, the state of (festival) exhibition — perhaps all these are inseparable to festival programming — but can you talk about the relationship between your own creative work and your work at organizations like Images, CFMDC and The Funnel? Do they inform each other and, if so, how?

Mike: What is the relationship between my movie making and curating? The commonplace is that if a movie is selected for a festival or a gallery, it will be visible. Likewise, if one includes a shot in a film, it is clearly on view, as opposed to the heaps of material in the trim bins or littering the floor. But every artist will tell you it isn’t so. Many shots in movies are invisible, or nearly invisible, because of the shots that are follow or precede. They might function as transitions, or as a way to set up a particularly memorable moment. They can rush past too quickly to be seen. They might produce a feeling tone, or contribute to an atmosphere, instead of offering a specific articulation. A movie festival is a staging device for motion pictures, and it has particular ways of rendering work invisible. If your two minute short falls just before a feature length killer, you have just been buried. If it plays just before the most boring and repetitive movie ever made, you can be sure that when the curtain falls, the only experience with stick is the one that created so much aversion. And this question of what sticks and what doesn’t stick is rarely considered. Most exhibitors imagine that the act of selection guarantees visibility. A fundamental error.

The second systemic problem with motion picture exhibition is the sequencing of short movies. I have experienced this hundreds, perhaps thousands of times, and rarely well. Why is it so badly done? One of the reasons is that the programmer imagines that all of the work is equally visible, or at the very least, visible. But when you strike out from the premise that the machine you are operating in is working hard to ensure that a portion of its displays are invisible, different choices follow. Most fundamentally in the area of sequencing. The dominant habit pattern in motion picture sequencing is to group works with similar themes or formal approaches or subject matter together. This approach ensures maximum invisibility. It heightens the possibility that the works will blend and blur into one another, creating memory smudges and hazy, indistinct impressions. It offers up the programmer as a kind of meta-filmmaker, demonstrating their own meta-intelligence at the cost of the work itself, which function as ideas and abstractions. Most often, my experience is that the movies struggle to be seen beneath the din of the programmer, who is trying hard to drown them out. If one works from the premise that the task of the individual program, not to mention the festival itself, is to allow these works to be seen, very different choices follow. One tries to celebrate the uniqueness, the singularity, of each particular work and approach and making. Instead of trying to blend the singularity of each movie into a number of other likeminds, it is carefully separated from anything that might be mining similar veins, and is programmed in juxtaposition to different kinds of makings, so that individual differences can become clear. The way we create a group, or a community, is not through conformity to top-down ideas, but through a celebration of diversity. And this diversity is expressed through the sequencing of movies in a program. In this way, the form is not separated from the content.

Jane: There seems to be a number of key debates from 1980s and 90’s (e.g., film vs video, identity politics, national vs international). What kind of impact did these discussions have on your work at Images? Were there key debates and issues you had to navigate while at Images? Deirdre, for example, describes her time at Images as turbulent and unpopular because of a perceived/real shift away from issues of representation and identity to questions of art with a capital A, but it was the direction she felt necessary for the festival at that time.

Mike: For many years I was deeply involved with the Funnel, a fringe movie theatre that lived in the eighties. One of the reasons the Funnel died was because the people running the show became too certain about what fringe movies were. This is an experimentalist movie! And this is not an experimentalist movie! I wonder if it’s unfair to ask whether your question could be put this way: where is my avant-garde? Images had broken down the Berlin Wall between film and video from the outset, and had continued to show works from all sides for years already, I don’t think that was a concern. But I wanted to bring together expanded cinemas, 3D cinema, super 8, slide shows, etc. and bring them all into the space of the theatre.

I was less interested in national cinema expressions that some of the past iterations of the festival. In the eighties, firebrand Francoyse Picard headed up the media arts section at the Canada Council. She had a vision of a “cinema of resistance” that would be produced through the film and video co-ops, and exhibited through a national chain of theatres/galleries. If only it could have rolled out that way. I was sympathetic to fringe manufacture from the other Canadas of the heart, and certainly showed some, but was more concerned with the relationship between local and international creations, and as already discussed, between what was being made now and benchmarks of the field. My concern as a programmer was about community. The Images Festival is very different than say Oberhausen, which imports fest professionals, mostly from Europe. Or even Osnabruck, which plays to a more local crowd, but also internationalist fringe seekers. Toronto, by contrast, has a large and well informed independent movie sector, and it is this sector that makes up the core of the Images Festival audience. I wanted to show work by and for that community.

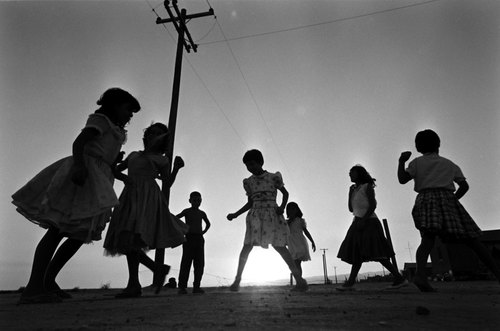

Questions of race and representation were never far away. I had wanted to produce the festival as a picture. What would that picture look like? Perhaps a web or a network. Making an approach to questions of identity and race meant engaging this picture, this network. I asked my friend Helen Lee, a film artist living in Korea, if she would put together a program of local Seoul work. Helen is someone who has a particular interest in dramatic forms, so it wasn’t unusual that the most narrative work of the festival arrived in her selections. What was surprising to me was that the audience for her screening was so different than others during the week, the auditorium was packed with Koreans. Unlike so many of the other programs, which were made up of motion picture cocktails, this screening could be identified and marketed to a specific community. And not incidentally, it was a reminder of how important it was that different communities had a chance to see themselves. The challenge of the festival was how to get different communities interested in each other’s pictures. How to let different parts of the web sing together?

Jane: In your conversation with Helen Lee (for Reel Asian Anthology), you talk about experiencing a white, male aesthetic at the Media City Festival. Others have expressed concern about the future direction of festivals like Images as moving towards a white, romantic notion of the purpose of art. What role do/have festivals play/ed in normalizing or disrupting this view?

Mike: Just to clarify: the Media City I was speaking about was more than a dozen years ago, and their programming has continued to shift over the years. It can be difficult to exist under the same name, and become identified with the qualities of that name, when practices turn so dramatically. Perhaps Media City exists as a series of entirely discreet, once-only presentation events, each of which runs for a single year under the name: Media City.

Is Toronto going through another white supremacist moment of avant-gardism? Are the movies, the panels, the programmers, the infrastructure staff of distributors, educators, and exhibitors largely white? If so, we can be sure that they will largely reflect their constituency. Just as Koreans came out to see a program of Korean shorts, qualities of whiteness are spread by whites. Without changes on an institutional level, it’s difficult to imagine this changing. You raise a strange and interesting question about the purpose of art. Does it have a purpose, an aim, an intention at least? And who decides what these are – the artist, the audience, or the programmer? I think the field of fringe media in this city has been lopsidedly white, and it resides within a likewise white-sided art scene. One of the questions that Helen’s program helpfully raised for me was: what is experimentalist? Surely the rules don’t exist engraved somewhere in the heaven realms. For an audience that has never seen a gay Asian top, or a transgendered point of view, these encounters are distinctly experimentalist, even if they might be situated within easily digestible dramatic movie forms. What I’m pointing out is only too obvious for the communities involved, but becomes harder to reach when the universalist canons of a white avant-garde are fired. They typically crouch underneath the banners of excellence and high standards. And of course, as Obama reminds us every day, you don’t need a white person to uphold good old fashioned white imperial values.

Jane: If we think about the role of the festival as an archive and history, there is a danger, as with any histories, of it being too narrow and written by a select few. Can or should festivals have a responsibility to be more inclusive and, if so, how? Or will this affect a festival like Images to lose its purpose in responding to and reflecting the changing direction of image arts?

Mike: I think there’s a problem when curators stay too long at their posts. Or for that matter, any administrator in any artist-run centre. I don’t believe that fringe media joints or artist-run anythings should be fiefdoms or empires. When a single curator lives at an institution, the values and inclinations of that person are inevitably reflected, and over the short term that’s a good thing, but over the long term I think it’s almost always unfortunate. Each programmer has their own blind spots, and the only way to cure them is to bring in different people, with fresh points of view. Otherwise the select few that you mention stand on guard and choke off the possibilities of a living, diverse culture.

How can a festival be “more inclusive” as you put it, while maintaining a distinctive identity? By nature, a festival is a machine that says no, it is a machine built for exclusion. What is wonderful about the Images Festival is the way they have built horizontal relationships with so many organizations across the city. It is a functioning web, while each centre has its own autonomy, they operate within a larger rubric. On the other hand the relationship the festival has with the city’s artists is not horizontal, but vertical. There is a call to submit. And what does it mean to submit? To be underneath, to be in a state of submission. To put it in psychological terms: the relationship between organizations is equal and fraternal while the relationship between festival and artists is paternal. I know and you don’t know. I am the authority and you will submit to it. How can this be addressed? Quite simply, by eliminating the “open call” (another misnomer), by stanching the flow of received works (and along with them, their treasured entry fees), most of which are turned down. What is the point of the open call? To receive a great number of works that will not be shown, and to provide revenue for the festival so that it can employ people to watch this work. What is the consequence of an open call? Maximal bad feeling. The more effective it is, the more people it reaches, the more artists will be turned down. The more bad feeling the festival creates. If your primary relationship to the festival is receiving rejection notices for your work, what are your feelings about the festival going to be? These paternal relationships are not the web, they are the anti-web. I am not connected to you, you are not equal to me, you are not worthy of my event. It’s OK for fests like Oberhausen that don’t rely on local populations to stock the theatre, but how can you ask the very community you are busy saying no to for support? Of course the festival is busy repeating itself, like so many of us. But so many other festivals have open calls! Or: we’ve always done it this way! Or: eliminating the open call is anti-democratic! The old habit patterns can be hard to let go of.

Jane: Looking back at the 80s and 90s, the tensions and debates created a fertile ground for new activities and organizations but does the space for discussion/debate still exist between festival organizations in the city? Do you see changes in the ways that artist-run festivals/organizations work with each other?

Mike: I think you’d be better asking someone that works for a fest or an artist-run centre. I’m not working for an organization, and haven’t for many years. But let me risk a grossly overgeneralized comment: I think there’s less and more communication today compared to twenty years ago. Today I can email you. We’re in touch. We have this light touch of the email or texting. Twenty years ago we actually sat in the same space, or else we talked on the phone. When I worked distributing fringe movies, my most important information came from film artists who told me about venues, opportunities and possibilities that I couldn’t have imagined asking them about. When you shop online, you get the book you want with maximum efficiency. But that efficiency stops you from receiving the information you didn’t know you needed. The other books that derail you, and send you away in unexpected directions.

Jane: Festivals are incredibly important social sites but are we prone to idealize the festival space as a public sphere? You talk about the importance of encounters at festivals but you also liken them to malls. Can a mall-like experience allow for critical dialogue? Or what do festivals have to do to encourage potential reciprocity? [I’m thinking about your discussion with Yann Beauvais as pointing out a tension between festivals as a social site and as a way to experience work. I guess I’m still trying to formulate a good question about this…]

Mike: I think you’re asking about what kind of conversations do we need to be having, and where could these be taking place? I’m working on a project with Clint Enns, a young fringe maker from Winnipeg, who feels he has dropped into a city that is divided and sectarian. The programmers have already made up their minds and deport themselves quite apart from “the community.” What did he say? “It’s 1989 all over again.” Oh, I hope it’s not true. Does the Images Festival, or any festival, provide a place for real dialogue to happen, or even unreal dialogue? The most helpful exchanges I have are with friends when we’re showing each other works-in-progress. It is blunt and intimate and exciting, there’s nothing like it. I wonder where are the twentysomethings interested in the field? Why do I recognize so many faces when I go to screenings? Some of the current scene feels very old fashioned to me, the kinds of movies that are shown would have been very much at home at the Funnel in the early 1980s, and while I am not big on progress narratives, that was a moment when so little work had been shown, whereas now so much has been put on view, surely priorities have shifted. Or has the avant-garde been reproduced as a new form of nostalgia?

Jane: Festivals are also in a state of flux — the move between theatrical or gallery settings and online explorations may be inevitable. Some people question the future of festivals particularly if they move away from a shared public theatrical experience. Do you see the future of festivals in jeopardy in any way?

Mike: What does the crystal ball say? Will they live or die? At the current moment we are seeing a new frontier of monopoly capitalism take hold of the internet. One can imagine that their aims will be different than the interests of fringe media festivals. And what of the entire artist-run centre experience? In its earliest incarnations, it existed as a kind of proto-internet, a web of interrelated spaces and interactions. But these interconnectivities have been swapped out for social media posts and whatever tech interfaces lie beyond them. Not to mention a looming, devastating climate crisis. Now that the old dream of the revolution has been realized: that everyone will have the means of reproduction, what will we do with them? What kinds of worlds will we imagine from the frontiers of the new lives these tools will make possible? My greatest failure at the Images Festival was that I didn’t understand that what resided in the middle of the frame are not pictures but people. What was important was building places where people could interact, and this didn’t require more programming. Our lives are already too filled with programming. We need spaces that are not programmed, so that we can perform useless activities and have undirected conversations. Where can we go to practice what we don’t know, instead of our certainties? And now that we have swallowed the anti-time machines of the personal computer, where will we find the time? Where has all our time gone?