Originally published in de Filmkrant, November 2014

At the Curtocircuíto festival in Santiago de Compostela in October, a small but intense retrospective was devoted to the Canadian filmmaker Mike Hoolboom. Mike is not the kind of director who hordes and archives every last trace of his creative process undertaken over the past three decades — quite the contrary, he regularly withdraws some pieces from circulation, even to the point of junking them altogether. Some films only really work in a specific time, place and occasion, he explains; and besides, we already have too many films and videos in the world, too many images and sounds to deal with.

In a splendid Masterclass offered at the festival, Hoolboom offered his thoughts on the creative process, as influenced by Zen Buddhism. Something we need in modern life, he suggests, is attention — the ability to pay attention, to be attentive to people, things, faces, feelings that flow back and forth in any encounter. And immediately, I began musing on the tensions at the heart of the work of this prodigious artist — someone who is too little-known and celebrated on the international stage of experimental, avant-garde or (as he prefers to call it, more democratically fringe film.) Many of Hoolboom’s works, such as Frank’s Cock (1993) and Tom (2002), are strikingly intimate portraits of close friendships in the era of AIDS. Like in the late films of Stephen Dwoskin, the shadow of looming mortality is offset by rapturously lyrical celebrations of momentary epiphany: dazzling light from bodies, interpersonal happiness, everyday grace. But, on the other hand, these films are also a spectacle, projected onto a screen for an audience with prying eyes. This doesn’t bother Mike: every good film, he says, starts as a ‘threesome’ — with the third party being at, the start, a piece of technology like a camera, and then, eventually, the spectator.

But where, exactly, is the ‘attention’ factor in the blistering montages (mostly appropriated images) that make up most of the running-time of Hoolboom’s films? His films are not minimalistic, patient or contemplative — which is our modern cliché of cinematic attentiveness. All his films arise from what he calls a detour, a type of running free-association through a vast field of images and sounds — in order, usually, to finally return to something simple, such as the face of a friend.

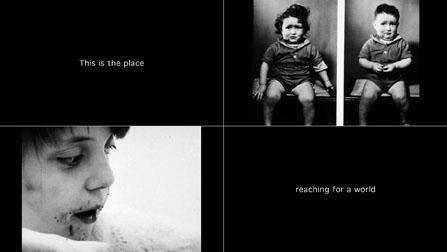

For Hoolboom, these images and sounds are what lies ‘between’ us — not in the sense of a barrier or disguise, but rather a living membrane that connects us. Many of his films, including Public Lighting (2004, newly re-edited) and the in-progress Scrapbook, address how our identities — for good and for ill — are constituted through imaginative projections and identifications. In Damaged (2002), he chose a set of random postcard images just as he found them in a box in a shop, and asked himself the question: what life could correspond to these pictures?

It is rare to find a Hoolboom film without narration, without a story of some kind — without an ‘address’ to the spectator, whether printed on screen, or delivered in voice-over. It’s what he does to keep his work intelligible and accessible — even to his mother, whom he imagines as his ‘typical’ viewer. But Hoolboom’s narrated stories work like the prose of Roland Barthes or the films of Terrence Malick: anybody, anywhere, of any age and in any kind of body, can inhabit these richly emotional ‘I’ and ‘you’ and ‘he or she’ propositions, these shifting signifiers that are not empty, but full of yet-unmade possibilities.

Similarly, we are never sure, while watching his work, how these stories started, or where exactly they come from: a real life (Mike’s, or somebody else’s)? Were they filched from a novel, a movie, a joke, a quotation? Are they pure fiction, reverie? And was the story written to fit the associative-flow of the image-sound membrane, or vice versa? The concrete answers do not matter: what matters is the flow, the wave that he offers, which we can catch and ride — if we dare.