Precarious Landscapes: a studio visit with Julieta Maria by Alexandra Gelis, Rea McNamara and Mike Hoolboom (March 2017)

Julieta: I began painting in the nineties. It started as a weekend activity but became nearly a full time activity before coming to Canada where I had my first solo show. I mostly painted imaginary women, strong women. I think it was self-referential, I was identifying with the subject, although I didn’t see it that way at that point. Then I took up photography, working with a collective of friends, working mostly outdoors and concerned with the relationship between the human subject and the landscape. We would pose for each other and I would say in my case I was after some surreal undertones, a kind of defamiliarization of the image, but never using Photoshop or collage or other kinds of compositing. I never took candid pictures of strangers since I felt it was too aggressive an action for my personality or way of interacting in the world.

Then I came here (Toronto) to York University and took a video class and began experimenting with myself. As with photography, I like video’s immediacy, it is less abstract, less distanced from the subject than painting. I also liked the time-based quality of the video image.

Mike: When you were a kid did you think you would be an artist?

Julieta: Early in my childhood I liked writing, and also I painted a lot. Somewhere along the way that shifted. By the time I was twelve I thought I would be a mathematician or study languages. I felt more comfortable dealing with logic or grammar, syntax, linguistics. I felt it was a safer space, less vulnerable, less revealing of myself and less subject to criticism.

Alexandra: How did you jump from those interests to the interactive work you made later about your family?

Julieta: I studied computer science and started programming, so I had that background. Once I started working with video, I also experimented with interactive video just because I was curious about it. I started experimenting with multimedia and made some interactive projects, although something about the medium always bothered me. I tried to make pieces where the interactive aspect did not turn the experience into a game or became the main aspect of the piece.

The piece you are talking about is an interactive video piece called Findings. It contains brief testimonies that provide limited access to the history of the family on my father’s side, who migrated from Palestine to Colombia in the 1920s. The piece is constructed as fragments of stories, drawn from everyday conversations around the history of my grandfather’s generation. The projected videos included a visual exploration of archival photographs. The emphasis was placed on the phantasmagoric quality of photographs and the absences that they stand for. The work was more about ambiguity and memory gaps than the search for facts and truth. The installation consists of the projected videos and objects (lamps and tiles) that are placed on the floor. The tiles have a printed text and decorations that resemble the mudéjar (Islamic) design. This Arabic influence can be found in Colombia due to Spanish colonization, and there is a strong presence of immigrants from Arab countries, more specifically Lebanon, Syria and Palestine.

On the wall, the projected videos change according to the movement of the person standing in the space. The spectator triggers one of six different videos when they stand in front of each of the tiles, positioning themselves between the light source (lamp) and a camera. The difference of light and shadow is calculated through the camera input to determine which video to trigger. The videos were controlled using Cyclops and Max/MSP software.

I was never sure the installation was successful, although it might have worked at a conceptual level. It was interesting to look at the audience deal with the interruptions in the video as they moved from one place to the next. It was somehow a frustrating experience and it forced people to be still and have patience.

I also made a single-channel version with all the sections pieced together (Findings (8:43 minutes 2007). Both include a photograph from my grandfather’s house in Palestine. He was able to go back to his birthplace only once, as it was hard for him to travel.

I made another short video called The errant Palestinian (3 minutes, 2007) that uses family portraits and photographs of my grandfather. It’s based on the poem “el palestino andante” by Alvaro Medina, which paid homage to my grandfather’s story. My grandfather died without being a citizen of any place. He never had a passport. He was never a citizen of Colombia, even though his children and grandchildren were citizens.

Mike: This is a very different kind of making than your single-shot camera performances. You didn’t want to continue in this vein?

Julieta: I guess I didn’t. I was also doing performances for the camera but I was experimenting with other things. In the end, I thought the work was too poetic, it needed to be stronger. I had incorporated text, words, speech in these videos, but later I decided not to do any of that, and focus more on a visceral connection with the audience. Less rational, more emotional, body-to-body dialogue.

One of the first movies I made was called On Water (4:48 minutes 2003). It touches on feelings of fear rooted in childhood. Fear of nature, change, the fragility of life, and being alone. It is a video where I play a lot with text, with the image of the text. I visually move through a poem so that the plasticity of the text becomes important, and the signifiers are destabilized. It just shows me setting up to do a trip that involves crossing a body of water.

Alexandra: Julieta is an excellent painter.

Julieta: You’ve seen my paintings?

Alexandra: Yes, at your mom’s house!

Julieta: Oh yes.

Alexandra: I have the feeling while watching your videos that you are still painting, that the colour and composition are painterly.

Julieta: I agree that for me the composition of the image is very important. Although in my video performances I undergo a process that is also central to the work, they always start with an image in my head, and everything else happens within that frame. Every time I talk about the video Exercises in Faith: Soil, I make reference to a painting by Alejandro Obregón and also to a painting by Holbein The body of the dead Christ in the Tomb, as influences in the creation of the piece.

Image no: XIR70421

Credit: The Dead Christ, 1521 (oil on canvas) by Holbein, Hans the Younger (1497/8-1543)

I made a series of videos on the theme of violence called Exercises in Faith (2010-2011). I am at the centre of them as the performer. (I can’t do live performance, only performances for the camera). The series is very loose, sometimes I take videos out and sometimes I add some because I see new relationships between them.

Exercises in Faith: Soil (4:06 minutes 2010) was made in a single shot, and it’s the first in the series. It shows my face in profile as earth is poured onto me, filling my mouth. I tried not to move and allow involuntary gestures to take over. I tried to be as quiet as possible while the earth was being poured into my mouth. The open mouth suggests a willingness to receive the dirt. It’s an unresolved situation, as the soil keeps falling and accumulating. The soil comes from above, as a kind of fate. (To Alexandra) Were you there?

Alexandra: Yes, I was behind the camera actually. (laughs)

Julieta: I was reading about paramilitary massacres in Colombia and the relationship between perpetrators and victims. The image that came to my head was not being able to speak or breathe. It was an image that also came from the mass graves where earth was poured directly onto bodies. I was thinking about the relationship between the female and nature/earth, but from the angle of something menacing instead of nurturing. There’s a certain cruelty in nature and in human nature. It’s departing from the idea of nature as nurturing because nature is also death. The profile of my face with the soil forms a kind of landscape. The landscape is the source of ideas about identity and dreams of belonging, but it can also swallow the subject and become a nightmare.

Exercises in Faith: Bird (1:52 minutes 2010) is also made in a single shot, like all of the videos in the series. Although in this one I edit the action so that it fades to white several times before being reactivated again. In the video I’m holding a canary tightly in my hand which is shown in close-up. It is usually shown on a loop in an installation.

Rea: Were you playing with the canary in the coalmine idea, the canary as harbinger of disasters to come?

Julieta: At the time I wasn’t aware that canaries were used in coalmines. When I made the video I was thinking about experiencing absolute power over someone and the radical potential of harm. The efforts of the canary to break free (beating wings, resistance) are hopeless, it’s a cycle that is never broken. I had also read that the paramilitary torturers would name their victims after animals, sometimes domestic animals, in order to strip them of their humanity and objectify them. I was thinking about the de-humanization of people and animal subjectivity. I wanted to present a mundane action, it’s not unusual that people should grab their canaries to cut their nails for instance, but I wanted to decontextualize the action, and I think the video gives the animal a subjectivity.

The reading I am refering to is Anthropologie de l‘inhumanité, a book by Maria Victoria Uribe. She’s a Colombian anthropologist who presents research on a series of massacres committed by paramilitaries attached to the drug cartels and the government throughout the 1980s. She details some of the imagery used by the assassins — the name-calling, the names of the groups and the characters they assume inside the group.

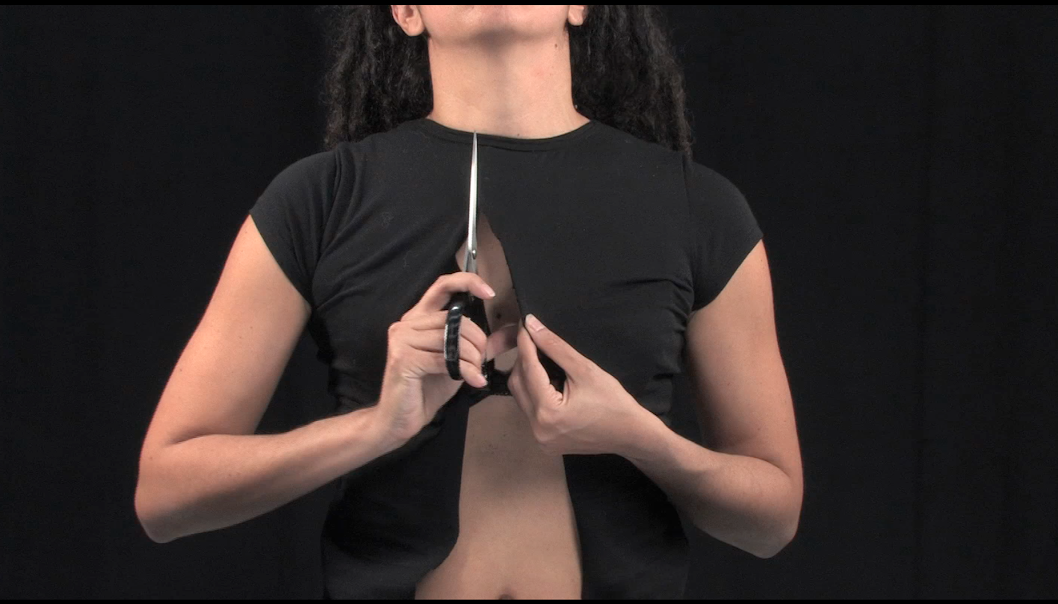

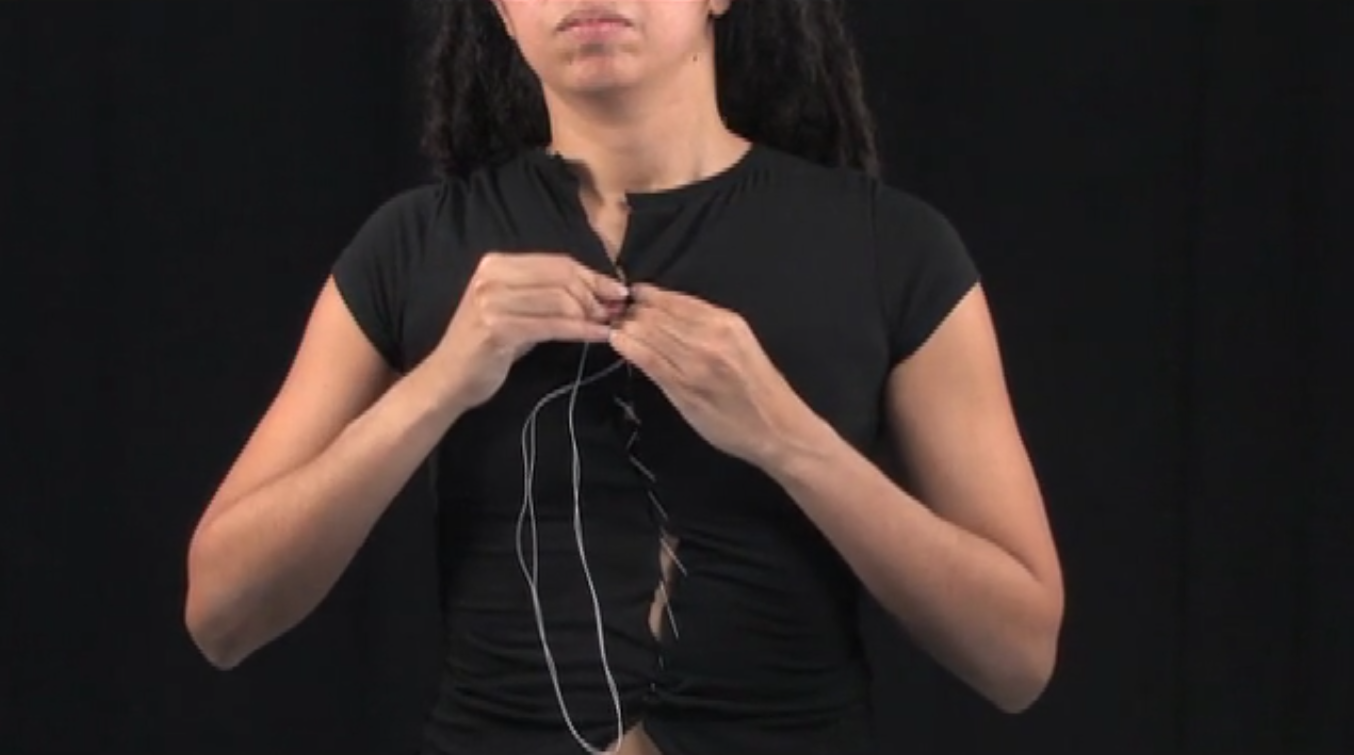

In Exercises in Faith: Cut (6:15 minutes, year) I sit in front of the camera, wearing a black t–shirt with a black background. It is a medium shot of my torso, from my navel up. I am facing the camera, but my mouth is the only part of my face that enters the frame. I do a vertical cut of my t-shirt with a pair of scissors, upwards in the direction of my neck. I put the scissors down and then I pull out a needle and thread and start sewing the shirt in the same direction. The action is performed blindly, without moving my head.

The motionless neck speaks to a disconnection between body and head, suggesting an emotional detachment of the subject from herself and from the operations performed; the subject’s lack of eye contact with the hands makes the cutting and sewing awkward and clumsy.

Alexandra did the camera in this video too. I get nervous performing in front of people so I had to ask Alexandra to leave the room after we had set up the camera frame. I was thinking about the effect a traumatic event has on the world, it becomes part of the everyday objects you have around you, it enters the relationship you have with those objects, and questions to what extent they can be repaired. I was thinking about places where catastrophes had occurred, and how memories of those events are folded into the every day, to use an expression by Veena Das. They are not something outside our day-to-day interactions with places or people. I needed to explore that.

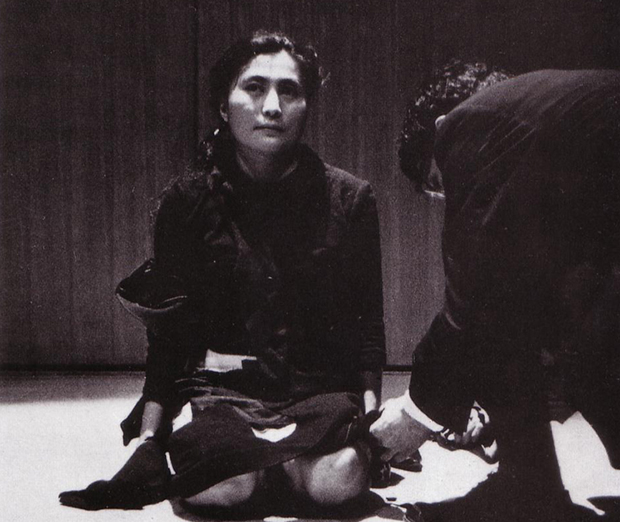

Mike: Yoko Ono did a famous performance called Cut Piece (1964). The score states: “Performer sits on stage with a pair of scissors in front of him. It is announced that members of the audience may come on stage — one at a time — to cut a small piece of the performer’s clothing to take with them. Performer remains motionless throughout the piece. Piece ends at the performer’s option.”

Julieta: The audience is central in Yoko’s piece but not in mine. It was about what they could do to her and the ethical limit of actions towards a passive and vulnerable stranger. I think Exercises in Faith: Bird relates more to her Cut piece. My work is obviously more controlled, I don’t give myself to people in that way. It’s another kind of reflection.

I began work on another series in 2010 called Reconstructions. Reconstruction #1 (9:50 minutes 2011) shows a white porcelain toy, a harlequin/mime that I found in a thrift store. I break it with a hammer and then reconstruct the head. It turns a three-dimensional object into a two-dimensional object. I’m trying to restore something, but it’s being done very poorly. I had the idea for a long time, and then I found this doll.

Rea: I see what you’re saying Alexandra about her painting background showing through.

Julieta: When I think about making a video I think about the image first. The process, on the other hand, can be difficult. I’m often doing something I’m not comfortable with. Even making the video with the bird was very stressful. I value the process, but during shooting I’m just trying to get through it.

Alexandra: I feel that you have a long mental process. You have deep thoughts, you go into the ideas and feelings, you process them a lot, and then the action happens quickly.

Julieta: Well I’m not too productive. Everything takes a long time. I think it’s because I don’t act on ideas immediately. Once I have the image I generally wait to see if the image sticks, if it’s strong enough. Sometimes the actions make me uncomfortable so I don’t go for it right away. I often dread having to do it.

Reconstruction #2 (7 minutes 2009) shows an image of grass as seen through a mirror, being broken by a hammer, and then the attempt at reconstructing the mirror/image by putting the pieces together. Containment is a kind of violence that holds together forcefully that which would otherwise burst open, keeping a distance in our connection to the real.

I made many Reconstructions, some more successful than others. Some are only exercises. In this one, Reconstruction #3 Cup (17 minutes 2009) I break and put together a porcelain cup, to form a two-dimensional mosaic. I don’t think I’ve ever shown it.

Exercises in Faith: Embrace (6 minutes 2012) was made a couple of years later. In this video I hold a fish close to my chest while it dies. The video explores my relationship with a living animal normally destined for consumption and finds common ground in the cycle of life and death. I embrace guilt and embrace what is other while suffocating it in a sacrificial rite that intends to take the fish out of its place as an object of consumption and imagines a continuum or connection based on our mortality.

The image runs forwards and then backwards, it’s a palindrome. I wanted to take a moment and expand it. It shows the inevitability of death and then tries to reverse this progression. The image stays in the agony of dying. I wasn’t exactly thinking of resurrection, instead the space before death is inevitable loops, we linger before death. I took the fish from a beach where fishermen set out every morning with nets. I took that fish as soon as they caught it and walked with it to a nearby beach to record that scene. It was shot in Santa Marta, Colombia.

This was one of the videos I dreaded doing because I am squeamish, and was especially distraught about handling something that is in agony. Fish and reptiles are the absolute other to me, so the whole process made me anxious. Our relationship to fish, going out to sea and catching and killing fish is usual, although it is not something I have ever done. But this limit between life and death is something I’m afraid of. I’m holding a live creature that is dying, knowing it will happen to me too.

Rea: Did you always know that you would source the fish from the fishermen?

Julieta: Yes, that was the idea from the start.

Alexandra: There’s an interesting relation between Embrace and Bird because you loved that bird, you took care of it for a long time.

Julieta: Yes, but I made the video as soon as I bought her. She came straight from the box. I bought the bird for the project, but we were together for five or six years.

In Embrace I’m killing the animal by holding it. It relates to the bird piece, since a fish is seen as an object that can be consumed. I’m killing it but I am also acknowledging what we both have in common, our mortality. It was important that I’m holding the fish, I have it close to my heart, feeling the death of this fish that’s becoming an object. I’m also acknowledging that I’m a predator.

Limpia (2:25 minutes, 2013) means clean. It also means spanking, when parents reprimand their children. It’s a single shot that shows my mother licking my face. She attended an artist’s talk I gave a week earlier, that’s when I took a chance and proposed this action. She said yes, but hesitated when she found out she had to appear topless. I needed this animal quality and didn’t want any distractions from the image.

It turned out she was much more into this action than I was. When I described to her what I wanted her to do she just took charge.

We performed the action three times. The first time she had a top on so we had to do it again. She was enthusiastic while I was the one dreading it. My instruction was simple: I told her to clean my face with her tongue like a kitten. I didn’t tell her for how long or what to do first. She stopped when she felt she had done the job. I had a hard time looking at the footage afterwards. It’s too intimate for me, to have her tongue all over my face, but I think it was good for our relationship. It was the first time she was in a work of mine.

Precarious Landscapes is the title of another ongoing series. This is the first one (Precarious Landscapes: Fire, 3:41 minutes 2011) in the series. I made a version in super 8 and another in video. I’m lighting small pieces of paper, dropping them on the ground, then putting the fire out with my feet.

It was shot in Cordóba, in the middle of Argentina, in the foothills of the Sierras. I worked at the site of a former detention camp La Perla (active during the late 70s) where people were brought and disappeared for political reasons during the dictatorship. The beauty of the landscape surrounding the area struck me. There’s a history to this place that’s not completely evident, despite the museum on that spot. I wanted to show that it’s not possible to walk effortlessly in that place, there are fires that need to be attended to. There was a construction crew working by the roadside that you hear on the soundtrack. The landscape is on view, but the path I walked on was closer to the road. I left the sound like that, to suggest other spaces.

Mike: Did you go there to make this movie?

Julieta: No, I went there to visit and thought about it, left, and then came back to shoot.

I started another series called Getting There. Getting There: Digging (20 minutes 2014) was shot during a residency I did in Taiwan, and the site of the video is Green Island. Political prisoners were sent there during the Taiwanese martial law period under the Kuomintang (1949-1987), especially in the period known as the White Terror.

The video is a single shot, very wide, showing the landscape and the ocean. I walk into the frame and dig a hole for twenty minutes and then sit inside it. It is more of a piece for a gallery space, it’s not really made for single-channel screening.

For me it goes back to the theme of beautiful landscapes that have histories attached to them. The former prison of Green Island Lodge is mainly a tourist destination today.

Rea: I was thinking about the futility of this gesture because you’re using such a small shovel.

Julieta: Another artist was holding the camera for me, and told me later, “You dig like a girl.” (laughs) I wanted to be a minimal figure in comparison to the large landscape. I’ve changed focus from filling the screen myself in the earlier works, to landscapes where the figure is lost. I wanted to dig a hole deep enough that I could hide in it.

For Getting There: Newfoundland (8 minutes 2015) I took a summer trip to Newfoundland with Ben Donoghue where he was shooting a film documenting hunting cabins. We stopped at this place on the way to Conche (population 225), on the northern peninsula of Newfoundland. It’s the French word for shell. In this video I perform a very simple action, walking naked from the far end of the frame across the screen towards the camera. It’s a single, very wide shot of a dried up riverbed, filled with stones. The water sound is from water running nearby. I’m following the river path but it’s very hard to see me. The shot starts when I enter the frame, and ends when I leave the frame. You are not able to see me right away, and if I don’t move too much the viewer loses track of where I am.

Alexandra: Why did you want to make an action here? Why did you say stop, I need to be naked in this place?

Julieta: I’m not sure but I thought about an action like this when I was in Taiwan. I had a visual impression, a picture of a place with a lot of rocks where I was walking. I was thinking about the difficulty of walking that path without shoes, about being vulnerable in the landscape, in nature.

Untitled (El Salado) (5 minutes, 2017) is another movie I’m still working on. It was shot in super 8, but there was a problem with the film processing, so the image isn’t too clear. I like it like that, though. It was made in the plaza of a Colombian town called El Salado, where there was a massacre in 2000, in a soccer field in front of the church. 66 villagers were lined up and shot by paramilitary forces who had the support of government troops.

In this film you see a frame that includes the former soccer field and the church where the paramilitaries confined people and the killings took place. In this video I walk from the edges of the frame towards the center, towards the field before the church. I wanted the action to be very simple, and repetitive in nature, like a permanent revisiting of the site, of the different paths converging on that field.

As technology progresses you project a magical quality onto older technologies, they seem full of wonder. Film is analog and chemical so the light bouncing on the subject leaves a direct imprint on the material, the presence of the subject is more indexical. I’ve been shooting video all the time, but I wanted to experiment with film. Maybe it’s Ben’s influence as well. I’ve always found the materiality of film very appealing. But especially in my earlier camera performances I felt the need for the immediate feedback that video makes possible. I can turn the screen towards myself, using video as a mirror. I used to work by myself very often, and it was an easy way to be certain about the results and evaluate and change things right away. But now that I’m part of a larger frame I can imagine working in film more often. It’s part of experimenting. There’s more of a phantasmagoric quality in film, which I thought was appropriate for that site. And this piece also has a ghostly quality that was not of my doing, but happened during the developing process, perhaps due to the aging of the film.

The town was abandoned for three years after the massacre. People are still slowly returning though many never came back. Some couldn’t find their houses because they were overgrown with vegetation and trees. And the land has changed hands, corporations have moved in. This is a place where land has been taken away, wealth has been gained by occupying land. There were guerillas in that area and the paramilitary weren’t necessarily fighting the guerrillas, but displacing peasants. There were inevitable displacements because of the war, but war was also used as a way to displace people. It’s another form that war took in Colombia. It’s related to mining, oil, monocultures in agriculture…

Alexandra: I’m also from Colombia. When you say that you have something from El Salado… this is a painful name for us. It is a site full of pain, the history of Colombia is a history of violence. And it happened so recently, only 17 years ago. I feel the history of violence in Colombia in your work, beginning with Exercises in Faith: Soil, where you start from the ground, the soil. In Exercises in Faith: Cut you aim your scissors towards your neck as you cut through your shirt, and it can’t help reminding me of the way the paramilitary cut throats.

Julieta: The paramilitaries had different cuts they performed on people. One of them was called the tie. They would cut the neck and then put the tongue through the hole. I was reading about all that when I was making those pieces. The information is hidden there.

Alexandra: I can feel it as a Colombian because those memories are so strong for us.

Julieta: I didn’t want to make the references too explicit, but it’s important that the feelings are there. At El Salado I wanted to do something very minimal. I wanted to honour the site, and mark a constant return to that place.

Mike: Do you feel your work looks different when you show in Colombia, is it differently received?

Julieta: I haven’t shown here that much. People in Colombia recognize the complexity and politics. And as I said, there are also some references to Colombian artworks, like in the video Exercises in Faith: Soil, where earth is being poured onto my face, this feels similar to the painting La Violencia (1962) by Colombian painter Alejandro Obregon (1920-1992). Alexandra, he was your grandad’s friend?

Alexandra: Yes, my grandfather was also an artist. Our family had a strong relationship with him.

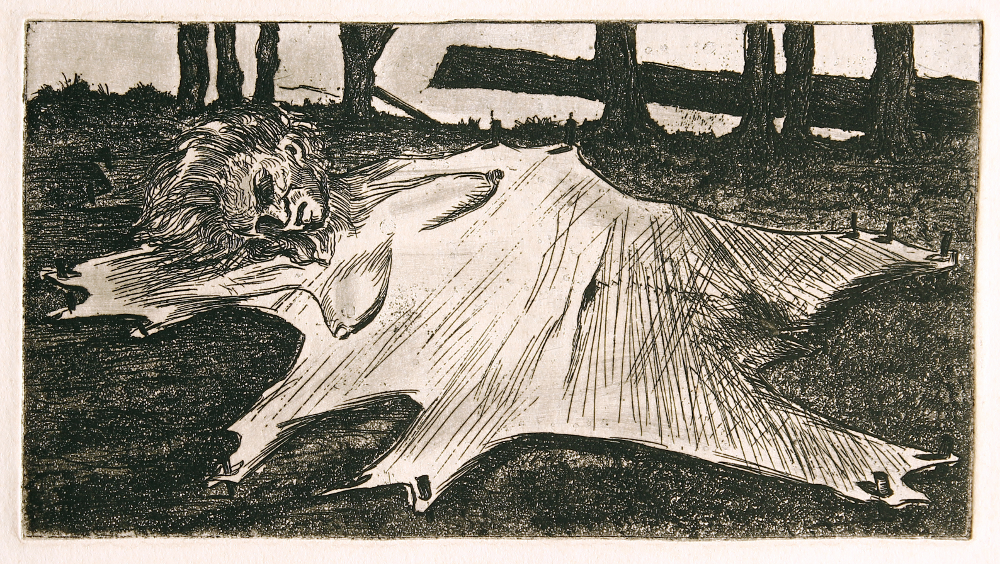

Julieta: This is Obregon’s painting of a pregnant woman who has been killed. At the same time she looks like a landscape.

Alexandra: Exercises in Faith: Cut reminds me of a series of work around the Corte de Franela. The shirt cut also known as tie cut or Colombian necktie was popularized during the period of violence (1940s and 1950s) between the liberal and conservative parties in Colombia. The victim was cut simulating the shape of a shirt around a neck.

Julieta, your camera performances remind me of the work of Juan Antonio Roda, Augusto Rendón and many more generations of artists portraying our life in constant war. Ricardo Rendón is one of the artists who commented from the graphics arts at the beginning of the century and Luis Angel Rengifo in his series “Violence” (from 1963) shows the long history of the violence in Colombia.

The discussion of violence and art in Colombia is an ongoing one, and it has renewed importance now during a time of “reconciliation” in Colombia. While the government negotiates with the FARC, Colombia is talking about the need to re-educate the nation to learn what peace means.

I feel that Julieta is part of a new generation of artists representing or working with the idea of violence in Colombia. There used to be painting and prints, now it arrives in video and performance.