Communication is Masochism: an interview with Parastoo Anoushahpour, Faraz Anoushahpour and Ryan Ferko by Alexandra Gelis and Mike Hoolboom Feb. 4, 2018

Ryan: We don’t have a collective name, though at the beginning we thought we should because it can be faster to articulate group aims and there are strategic advantages.

Faraz: In our work authorship and identity is always mixed.

Parastoo: The voice is always shifting.

Ryan: In some collectives, production offers anonymity. Solo practice is the core effort that the group supplements. In our case this is reversed, group work feels primary. We don’t get included in the discourse around collectives in Toronto partly because we’re frustrating to pin down. We oscillate between making works for cinemas and galleries. Sometimes a project needs space, or have focused linear attention. We devalue ourselves by oscillating between different environments.

Parastoo: Faraz and I grew up in Iran. I left when I was 18, Faraz at 16. We went to London where he studied architecture and I entered theatre design. Ryan lived in Victoria studying history. Faraz and I moved to Montreal and tried to make a film but it didn’t quite work, then we moved to Toronto to go to university and find a network. We all wound up in the two-year graduate program in Interdisciplinary Art, Media and Design at the Ontario College of Art and Design University. It was heavy on theory, but hands off about making. In reaction to the lack of production structure, we started working together there.

Ryan: We made two or three films.

Parastoo: It all started with a class assignment related to chance. We decided to play a game in the PATH underground, entering at different ends and staying until we found each other. Every ten minutes we would record something, either in writing, sound or video. It took us five hours to find each other.

Ryan: There were rules. We entered at the same time, Parastoo at the furthest north entry, I was west, Faraz east. We weren’t allowed to leave until we’d encountered each other. It happened six years ago but laid down some of the ways that we continue to work together.

Parastoo: The whole of idea of “the three” was to challenge or trouble authorship. It was a masochistic experiment in communication. Right after we graduated we had a residency in Berlin where we made another experiment. We started by recording ourselves talking for half an hour about what we wanted to shoot.

Ryan: We transcribed every conversation, and that turned into a script for the week.

Parastoo: We shot each other’s expectations. It’s an absurd practice because brains will never sync. The misunderstandings bring joy and pain. We tried to make an archive of the city based on our half-hour conversations. We shot for a month and wound up with so much footage. That’s how we made the first film.

Ryan: There’s no separation between our working selves and personal selves. Our relationships with each other are very intimate and intense. When you subject that to the scrutiny of recording, transcribing and working…

Faraz: Our way of working needed a structure. This project was like going to film school. We learned how to make movies.

Ryan: In Berlin we were focused on how we were going to work together. And that never stopped.

We used to say that our project was about the articulation of communication, but after five years of intense working it’s more honest to say that our work is about the difficulty or inability to communicate effectively amongst ourselves. You can never quite articulate your thoughts. As a result, you wind up making things that you wouldn’t have wanted or imagined.

Parastoo: We all shoot and edit. For a long time nothing happens and then a short sequence starts working without ownership. It’s like a puzzle where you take someone’s edit, and then someone else takes your edit. We work parallel to each other, using the same footage at the same time.

Faraz: We have a lot of footage, but we don’t know how to put it together. Once a path emerges, we start to build around it but the work is still circulatory, it moves around.

Ryan: Berlin set a pattern for how we work. Our location produces a context. We shoot and fill hard drives with content, cataloguing it every day by name and camera, creating an archive of our interactions with these locations. We then work in the studio to find new relationships to this material.

Mike: Let me drop a Guy Debord quote in here: “In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. Chance is a less important factor in this activity than one might think: from a dérive point of view cities have psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.” (Theory of the Dérive, 1956)

Ryan: We share a studio because the process is spatial, we’re not just on a computer with a linear work flow. There’s usually some distancing from the material. We might project it onto a wall and refilm it, or print it out as stills. We try to create distance from the archive, and that encourages the three of us to work together in a space. There’s no division of labour, we’re all there for every step.

Mike: Can you describe your new movie Chooka (20 minutes 2018)?

Faraz: We were commissioned by LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) to work with the film archive of Jacques Madvo. He was a documentary filmmaker who made a lot of work before moving to Canada where he made twenty films for a TV series called People and Places, generic anthopological docs about countries and culture.

There’s always a fascination with material coming from pre-revolutionary Iran. In one section Madvo was invited to an event in the north where there’s a lot of North Americans, and kids going to school. What was this event? That’s when we said yes, we’re interested in making a project. There was also footage of a paper factory being built in the same region. What kinds of factories were built by Canada in Northern Iran?

We located the factory and the housing complex built around it designed for the engineers and workers. It was a mini-city with housing, shops and cinemas.

We happened to be going to Iran, though hadn’t planned on shooting. This gave us a purpose. We called my parents and told them we were going to this region, do you know anyone there? Yes, there’s a family living in a village 25 km away. Great, let’s go. Later my dad said this place hosted the production of three films (in 1972, 1978 and 1991) by Bahram Bayzai. The film crew stayed with this family, in the same house we stayed in.

Parastoo: It’s still a local legend. They take you on a tour saying: Mr. Bayzai and his crew filmed the chicken here.

Faraz: There are interesting parallels. The figure of the stranger was the central figure of Bayzai’s film. In one instance the figure of history comes back from the sea. Or there’s a kid who fled the war. We were also strangers coming from abroad, just as Bayzai’s film crew were strangers coming from Tehran.

Parastoo: The factory was a sensitive site. Entering wasn’t as much of a goal as accessing other spaces like the worker’s residences that we visited. When the revolution happened in 1979 all construction stopped and the engineers left overnight, abandoning the villas. After the revolution there was eight years of war with Iraq. The factory remains the only source of employment in the region, but it never took off, so it was turned into a recyling plant for paper.

The whole village works for the factory, there’s been a lot of strikes and labour issues. We had to be super careful about what we said and did, especially with a Canadian on the crew. Why are you interested? What do you want to say? It became tense quickly. Meanwhile back home there was a kid practicing English with Ryan everyday.

Ryan: There was the tension of the situation, and then at the house we hung out with an eight-year old boy, inviting him to come swim in the sea with us, or have food. This was the opposite of asking questions, it was a relationship for its own sake, and it evolved until it became the core of the film.

Faraz: We arrived with a curiosity to look for things, and he was the same, equally interested in us, and that’s what made the relationship interesting.

Parastoo: We discovered his cameras just before leaving. Sometimes kids steal oranges from the trees so 13 cameras were installed. The cams feed into his little laptop.

He was watching/videotaping our actions, our entrances and exits, but in such a matter-of-fact sweet way. The way he talked about this material was so touching.

Mike: Tell me about the strange odyssey of Heart of a Mountain (15 minutes 2017).

Parastoo: While on a three-month residency in Taipei we had a Google app (Google translator) that translated Mandarin into English, but also translated live visuals or graphics.

Faraz: We used two kinds of images to locate Taiwan. One was traditional sliced volcanic stones, which offer a link to China and Chinese landscapes. These are origin stories.

Parastoo: They’re on display in a museum. The stones are cut and framed and have names like “Mountains in Snow.” They’re kind of found objects.

Faraz: The other image was the Capitoline Wolf sculpture gifted by the Italian ambassador to Chiang Kai-Shek, after he set up his government-in-exile in Taiwan in 1949.

Parastoo: The wolf is a symbol of a civilization, a symbol of a place given to another place, or someone who has escaped another country.

Faraz: We force the app to translate these images, because it’s always trying to find the image of a character and generating words.

Ryan: The software tries to create traditional sentence structures, it would flash words and then replace them. We recorded these attempts and generated a poem that became our script. This directed how we interacted with our time in Taipei. We shot certain things in relation to these generated poems.

Mike: There’s an object that blows up at the beginning of the movie.

Ryan: It’s a large pumpkin.

Mike: Is that what people do in Taipei?

Faraz: It’s from Virginia. After we had this text, we used it as a guide.

Parastoo: We asked Hector, the security guard where we lived, if he could read it.

Ryan: He asked us about the text because it wasn’t quite making sense.

The word for island in Mandarin is an ideogram showing a bird inside a mountain. Hector speculates that if you’re at sea and spot a bird, there might be an island nearby. In this movie words, objects and things make sense and don’t make sense. The film ends with a scene shot at the seashore as he reads a poem without subtitles. Because of the broken translations, it sounds like he’s not a native speaker of Mandarin.

Faraz: There’s another layer. When translating we used simplified Chinese, but in Taiwan they use traditional Chinese characters, so he couldn’t read certain passages. In the end he told us, “We don’t use these characters here, they’re from mainland China.”

Ryan: There’s also a disconnect between the Chinese characters and English translation, which is never direct. We wanted to create a different experience for viewing the film depending on whether you spoke Mandarin, English or both. There’s a space of miscommunication or misunderstanding between languages that is productive for us.

Faraz: The logic of the Google app is to consume another language, it grants foreigners the fantasy of accessing another culture completely. How could we work with translation that includes a gap?

Parastoo: To point out the way translation distorts and isolates, even as it gives an illusion of understanding.

Faraz: We open a poetic space, that’s where the film operates.

Ryan: We had to get permission from the National Museum of Taiwan who brought their stone slices so we could make high-resolution photos. These images were later translated. We were in the museum with the curator, working with these stones. They came to see the film about the stones in the museum and wondered where the stones were. (everyone laughs)

Parastoo: They were so not impressed.

Ryan: They allowed us to work with their stone collection in exchange for our footage. We gave them all of our high-resolution images, but I think they were hoping for something they could use for promotion.

Parastoo: The beach at the film’s end is where the stones are from. It’s a touristic destination.

Faraz: That’s how it works for us, how it makes sense. But when it goes out…

Parastoo: Then it makes no sense.

Faraz: There’s an underlying logic.

Parastoo: There is no secret. The idea for us is a game that keeps getting more serious because we’re living this life, this is how we survive. But it’s still a game. I think we need three people, and we need some kind of structure. The structure can become bizarre like in this instance, or it can be more straightforward, like in the Iran film where we’re going to a factory to visit a family. Those structures keep us together, I mean, keep our films together.

Faraz: This film examines events from a very close distance, in close-up. You’re looking at a guard overseeing something, but the camera only shows us the sweat on his neck.

Ryan: You’re too near to understand the context.

Faraz: How could you create a picture, a landscape, a portrait, through these details?

Alexandra: There are alphabetic gestures made over Faraz’s arm that lies across the frame. I thought someone was learning language. They aren’t local because the arm is hairy. The texts are poetic, perhaps from the I Ching (Book of Changes)? I thought you were reading the history of the land through rock stratas, the layers of history, which is similar to the I Ching’s hexagram of six stacked lines. It’s interesting that you always return to the image of the arm, where language is applied. You remind us that language is an embodied process. While there are many different cameras and scenes, they always come back to you. Your experience of Taipei has consequences in your own skin.

Ryan: The tension running through the film reflects our experience in Taiwan. There is a recent history of violence and displacement that isn’t present in the ordered social environment. Instead, you see the presence of state power. There was always the question: where is the conflict? It’s been pushed underground. This sensation is physically evoked using close-ups.

Parastoo: It’s repressed within individuals and social settings. That’s what we’re making an image of.

Mike: Could we speak about Bunte Kuh (5:25 minutes, 2015)?

Faraz: At the end of the self-archiving project in Berlin we came across a family album. We asked a German-speaker to read the back of a found postcard, translating on the fly while we recorded, so there are hesitations. It’s a generic account of a trip to Hamburg where he meets his cousin at the train station before going to a restaurant and eating schnitzel. Then we flipped the postcard and asked him to describe the picture of an old-style restaurant in Hamburg called Bunte Kuh. There are two texts: the travel narrative and the image description. Both narrations feature pauses and hesitations that we found interesting, a space opens. We used these narrations as a guide for the film.

Ryan: We made two projects in Berlin. We came back to Canada with a lot of content and wanted to enter it in a different way so that it could hold three subjectivities. How could you include three voices in the space of a film? Still feeling frustrated at our process of conversation scripts and shooting in Berlin, we wanted to defamiliarize the material, rupture it and find another structure. The translated postcard became a way for us to look at everything we’d done from a new perspective.

We went into the studio with 40 hours of footage from Berlin that we projected and selectively refilmed, using a zoom lens to reframe. We overlaid sounds and spoken text in a kind of performance.

Parastoo: For a week, that’s all we did.

Ryan: When you’re previewing video files on a computer you can open files using the space bar. That’s how we moved quickly through our huge archive. As we were flipping files we would see these interlacings…

Faraz: We think of it as hand-processed video.

Ryan: We started opening files very quickly, one after another, in a rhythm, and if the rhythm was off we would do it again. It was like playing rhythmic sounds in the space, using the arrow keys on the computer, while someone was always using a telephoto lens to zoom in on parts of the image. That produced a lot of new content, and we edited that to the translated postcard.

The movie has a narrative quality of remembering, a flickering memory. In the end there’s a key change, it feels like there’s been a death that reconfigures what this memory was, or the perspective the person is speaking from. We had somehow arrived at that mood, we were brought to this darkness in the end.

Faraz: Bunte Kuh is the name of the restaurant, it means “colourful cow” or “spotted cow.”

Parastoo: It’s a fictional creature. But it’s also the restaurant where the writer eats with his cousin. The reader’s words fall apart because of our manipulations, as if he’s losing consciousness, and the images become more fragmented which brings on a feeling of absolute doom by the end. For me it feels like there’s been an accident. Someone’s dying and the ambulance has come. There are sounds around you while you’re having flashbacks, memories of a meal you had before the catastrophe.

Faraz: We tend to have key changes at the end of our films. We enter a different mode.

Ryan: And that changes what you think you’ve experienced.

Faraz: It’s a pattern.

Mike: What’s next?

Parastoo: The Peacocks Came With the Clouds started as a solo project. I went to a couple of Kurdish villages in northern Iran collecting embroideries particular to the region. They’re not precious, only made with basic white cotton. I collected them for years and then decided to go find who made them. It turns out they’re no longer made today, but for a hundred years women sewed these decorative cloths that hung in front of their clothes in a closet. They would embroider them as kids before they were married (because they married so young), and would take them to their new home as a kind of dowry.

The Kurds are a minority in Iran. 500 years ago a million Kurds were deported from the west to the north-east, near the border between Iran, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan. They were moved to break up the Kurdish population and control the uprisings. After the forced displacement, they developed their own dialect that is a big part of the film, including songs while they do chores, embroideries, wash dishes, perform repeated actions.

After meeting the women I returned with the three of us plus a theatre director friend, Davood Kheradmand. We had access to a nursery school in the region so we proposed a workshop with kids for two weeks. We interpreted the textiles and had workshops on recording sounds and images. The idea was that their stories would become a play at the end, which was performed.

It’s going to be a feature film that brings together images of the past with images in the landscape. Language is central because for years their language was banned, there’s been a long history of repression.

Ryan: After Iran we went to former Yugoslavia – Serbia, Slovenia and Croatia. It began as my project, but now we’re all working on it, and it’s being edited now. I made a film in Serbia two years earlier called Strange Vision of Seeing Things (14 minutes 2016) that is about the traces of the NATO intervention at the end of the Kosovo war from March-June 1999. I wanted to compare the presence of conflict that can be read in the landscapes of Belgrade versus other parts of former-Yugoslavia like Kosovo where the conflict has been erased and built over. The project is interested in traces of a historical event, turning to subjective recountings of people who break down the grand narrative of war by telling their own stories. You’re never really sure of where you are.

Parastoo: There’s a young person who was high on acid for the first time during the bombing of Belgrade. He enjoyed his experience, but the next day he found out how many had died.

Ryan: There’s an underlying personal searching and quest. My grandparents are from Slovenia, my grandfather worked in the machine tool industry and relied on imports from Yugoslavia. Growing up in the 90s all I heard about was the conflict. Today, the textures of my family’s office and domestic spaces are structures for me to see through.

Mike: A question about collaboration. Even though you have family roots and a driving personal necessity, if the other two decide the focus needs shifting, you’ll swing with that?

Ryan: Parastoo, you went on your own to Iran first, just like I went to former Yugoslavia, but we both needed to return with the group knowing that something else would happen, and in both cases, it did.

Parastoo: You destabliize your own intentions. (everyone laughs)

Ryan: There’s another project initiated by Faraz in Cathedraltown.

Faraz: The Cathedral of the Transfiguration is a giant church built in Markham during the 90s. When we went to see it, we realized an entire town of 3,000 residents was being built around it. Cathedraltown is being marketed as a serene European village with a cathedral at its centre, a fake urbanism. It’s being sold to Chinese newcomers. The cathedral is used as a way to locate and sell the location, granting the land an identity, even the pope came to bless it.

Parastoo: The idea is to go and live there.

Alexandra: How do you know when a film becomes an installation?

Parastoo: It’s about the scale of the project. We’ve been going back and forth to Cornwall, Ontario for years. The material we’ve gathered there needs space. There was never an impulse to make a film. I’m trained in putting narratives into space, it’s always joyful to do that.

Faraz: None of us went to film school. Our backgrounds are in making objects or experiences.

Ryan: We’ve worked on the Cornwall project and the building of the St. Lawrence Seaway the whole time we’ve been together. We wanted to make a series of exhibitions, like chapters in a book. We were dealing with how a place is narrated, how the Indigenous people have been displaced, and their narrative relation to this landscape, and settler communities who have also been displaced and how they narrate the relationship to this land very differently. Sometimes you need the focused duration of cinema, sometimes narrative elements can be more open and require affective space.

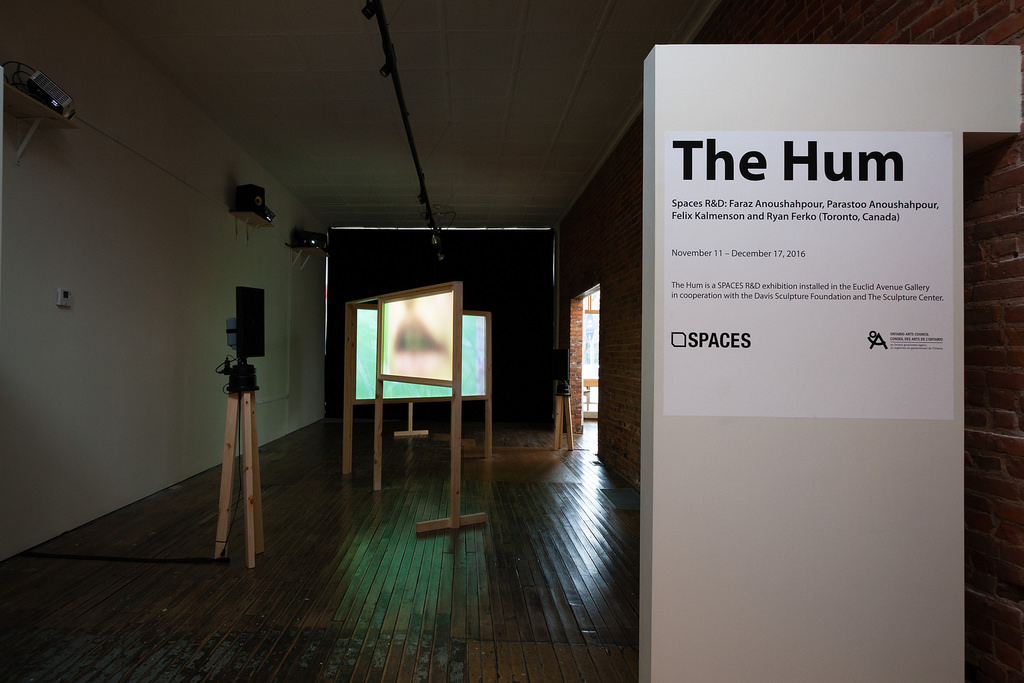

Parastoo: For Signal to Babble (The Hum) we made an elaborate installation about the sounds that plague residents in Windsor, Ontario. We collaborated with Felix Kalmenson on this project. It’s a humming bass sound that comes from a factory on the Detroit side of the river. There’s a community obsessed with the sound who keep a Facebook archive. They might write “I think I can hear it right now on the hill” and then we would drive to the hill.

Ryan: Like storm chasers.

Parastoo: I think I heard it. No, I can’t hear it. (everyone laughs) We worked with the idea of hearing tests and cameras that turn sound into image. We felt the material had to be presented spatially, in a gallery, but it didn’t work, and now we feel it should be a film.

Ryan: No project is defined from the outset as film or installation. We always work with cameras and create an archive. We travel, have experiences together, and then there’s a turning point.

Faraz: In Windsor we shot so much less than we did in Berlin because we knew what kinds of things we were looking for. Even though we are led by events, we’re not obsessively recording everything.

Parastoo: We’re growing up together. When Faraz looks a certain way you know that something is going to happen. (everyone laughs) When Ryan starts walking around in circles we know that something is happening. These are codes we know.