- The Loved Ones (pdf)

Originally presented at The Funnel, Toronto, October 1984

The Loved Ones

Program One: The films of Tom Chomont

Ophelia and The Cat Lady 2 3/4 minutes 1969

Phases of the Moon (The Parapsychology of Everyday Life) 6 minutes 1968

Oblivion 6 minutes 1969

Razor Head 8 minutes 1981

Joe’s Maison 5 minutes 1984

Endymion by Joseph Glin 9 minutes 1978

Love Objects 14 minutes 1971

Minor Revisions 11 minutes 1979

Untitled 9 minutes 1985

Multiple Exposure 9 minutes 1985

Program Two

Fuses by Carolee Schnemann 23 minutes 1964-67

Sigmund Freud’s Dora by Anthony McCall, Claire Pajaczkowska, Andrew Tyndall and Jane Weinstock 40 minutes 1979

Program Three

Standard Gauge by Morgan Fisher 35 minutes 1984

Bedsitters by Frans Zwartjes 18 minutes 1968

Eating by Frans Zwartjes 10 minutes 1969

Spare Bedroom by Frans Zwartjes 15 minutes 1970

Program Four

Asparagus by Susan Pitt 10 minutes 1979

Baby Green by Ross McLaren 10 minutes 1974

Thriller by Sally Potter 35 minutes 1979

Program One: The films of Tom Chomont

There is a stronger feeling of the personal in Tom Chomont’s films than in even Gregory Markopoulos or Jack Smith. These are films drawing on the filmmaker’s personal circle; a lover in Oblivion (1969, a group of polymorphous perverse men, women and children in Love Objects (1971), a soldier friend in Minor Revisions (1979), a man head-shaving and tying up his lover in Razor Head (1984) and so on. The images have an intimacy conveyed by the use of close-up and repetition, suggesting the cherished importance to the filmmaker of, say, this moment of peeling an onion (Minor Revisions), or the way that a loved one takes off his underwear (Oblivion). The sense of the specialness of these otherwise banal activities is often heightened by a certain strangeness in the filming, much of negative reversal, superimposition or remarkable set-ups such as that in Minor Revisions, where a man’s genitals are glimpsed from beneath in a hand mirror laid on a grey towel. The images, seldom held for more than a few seconds, are repeated and recombined with a strong rhythmic sense, so that the overall effect is both of evanescence and intensity, the intimate moment slipping from grasp yet registered with great tenderness. There is neither anguish nor camp in this work, no felt need to interrogate or assert a gay identity, just getting on with beign homo-erotic, amongst other things. Chomont’s films seem one of the few cases where gayness is incidental without being in the process marginalized. Perhaps now this can only be achieved in such a highly personal and intimate mode, where the questions of effect and representativeness, necessarily entailed in more public modes, do not insistently obtain.” (Now You See It by Richard Dyer, Julianne Pidduck)

Ophelia and The Cat Lady 2 3/4 minutes 1969

With Liz Reiner (Ophelia) and Carla Liss (The Cat Lady). On one level the films are portraits; on another level the first is inspired by reading about the painting of John Millais’ Ophelia and The Cat Lady is an homage to the horror films of my childhood movie-going.

Phases of the Moon (The Parapsychology of Everyday Life) 6 minutes 1968

With Lloyd Newell. “…It is a film poem and nothing else. A small miniature film poem, a jewel, if the word masterpiece is too stuffy.” Jonas Mekas, The Village Voice, October 1973.

Oblivion 6 minutes 1969

Tom Chomont’s short film is a shimmering fantasy of love and desire. The sleeping body of the lover drenched in shades of color and grain, creating an exquisitely senual memory of an unwound day at home. ‘Oblivion successfully blends elements from both the poetic and diary modes. In the process, Tom Chomont has produced one of the truly erotic works in cinema.’ (J.J. Murphy)

Razor Head 8 minutes 1981

The film was made on the request of the participants as a record of a two-day erotic ritual. 400 feet of film was shot and later permission was obtained to treat the material as an aesthetic composition, approximately 250 feet long. Originally the film was intended as part of a series of films dealing with non-genital sex and symbolic eroticism.

Joe’s Maison 5 minutes 1984

The film began as a record of the painter Joseph Glin and his series of paintings inspired by La Maison Des Mortes by Guillaume Apollinaire. After filming, Joe destroyed the paintings and closed his gallery, Shekhina, where the paintings were filmed.

Endymion by Joseph Glin 9 minutes 1978

With Tom Chomont, Rob Baker, Joseph Glin and Eric Ruff. Glin brought to the work a strong vision and familiar themes and imagery from both his paintings and an unpublished novel. I acted as a camera person, a technical advisor, cutter and assistant editor.

Love Objects 14 minutes 1971

With Pol Arias, Luc Mollet, Rggi Grovers, Henno Eggenkamp, Marianne Pituk, Paul Graaf. The project was filmed in Brugghe during a period preoccupied by readings on yoga, alchemy and Tantra. I thought in terms of the Medieval parable of Les Noces du Roi et Reine and the marriage of opposites… dichotomy resolved in unity.

Minor Revisions 11 minutes 1979

The original idea was to approach the physical/metaphysical as the theme of nourishment, both spiritual and gastronomical. This was somewhat altered by three visits from a frind entering the US army.

Untitled 9 minutes 1985

A second study of shaving as an erotic activity… a work in progress not yet titled.

Multiple Exposure 9 minutes 1985

The original intention was to make a portrait of a friend about to embark on a trip to Europe. The sexual undertones became unexpectedly overt and the form of the film became an attempt to relate the resultant images.

Program Two

Fuses by Carolee Schnemann 23 minutes 1964-67

Sigmund Freud’s Dora: A Case of Mistaken Identity by Anthony McCall, Claire Pajaczkowska, Andrew Tyndall and Jane Weinstock 40 minutes 1979

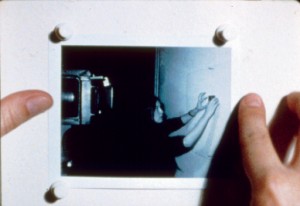

Fuses by Carolee Schnemann 23 minutes 1964-67

“Integral and whole-imagery compounded in emotin. We are equally, interchangeably, subject and object. As woman (image) and as image maker, I reclaim, establish and free my image and my will. Using borrowed Bolexes (wind-by-hand), natural light, the seasons over three years. Movement of myself and my partner filmed by myself. There was an additional cameraperson: the cat. Fugal structure; gesture, colour sequences, montage, superimposition, painting frame-by-frame, breaking the frame.” (C.S.) “A fluid, oceanic quality that merges with the physical act with its metaphysical connotation, very Joycean and very erotic.” Gene Youngblood “…hand-coloured, heated film of artist’s sex joy cycle. Tantric deployment on the emulsion, genital rites. Peaking, slippery in out cunt cock tongue tit. Watch Kitch, 17 year-old feline familiar to Carolee, a constant presence power transformer.” (Michael Berkely, Berkely Barb, April 19, 1974)

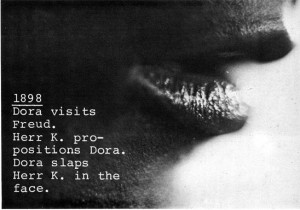

Sigmund Freud’s Dora: A Case of Mistaken Identity by Anthony McCall, Claire Pajaczkowska, Andrew Tyndall and Jane Weinstock 40 minutes 1979

A feminist critique of Sigmund Freud’s account of his first published case-history. ‘The film developed from a reading group on language and psychoanalysis in which nine people – including the four filmmakers – had been involved in the spring of 1979. Jane Weinstock and Claire Pajaczkowska had previously been in a women’s group reading ‘Dora’. Anthony McCall and Andrew Tyndall had made a feature length film about male fashion advertising and avant-garde filmmaking called ‘Argument’. Together we decided to develop a film using Freud’s famous ‘Fragment of an Analysis.’ We chose Dora as a text because it provides a site from which to discuss the intersection of several issues; a theory of female sexuality; the historical development of psycho-analysis as an Ideological State Apparatus often used by dominant ideology to try to reconcile women to their position within the family. Understanding hysteria not only as an illness but as the inevitable predicament of women who speak in a phallocentric language. To analyse that language, and how it represents. Freud’s representation of Dora, the representation of female sexuality in psychoanalytic theory, and representation in films. The film starts from the position that these processes of representation are not only a factor in psychoanalytic texts. They exist no less in a film’s shot-counter-shot that they do in advertising; no less in the iconography of the mother than they do in pornography.’ (Extracts from group statement, New York 1979)

Using inserts of television ads and pornographic films to interrogate woman’s status as the object of desire, it sets up a complex relationship between image, sound and text. Female lips in close-up recount a conversation concerning psychoanalysis, as we see a series of dates and events for 1882 to 1905, from the birth of Dora to the publication of Freud’s case history of her. Four dialogues between Freud and Dora follow. “[The film] begins with a monologue of a female voice, recapitulating a dispute about the ideological questionableness of psychoanalysis… In the main part, the treatment of Dora, a young woman with symptoms of hysteria, by Sigmund Freud, is reconstructed following his case study published in 1905. In the feminist discussion of Freudian theory, the case is already of central interest, because Dora eluded the grasp of reigning models of interpretation and the prescribed terminology of Freudian psychoanalysis and cancelled the treatment. The scenic reconstruction consequently aims at the inconsistencies and gaps of Freudian analysis.” (Kraft Wetzel)

Program Three

Standard Gauge by Morgan Fisher 35 minutes 1984

Bedsitters by Frans Zwartjes 18 minutes 1968

Eating by Frans Zwartjes 10 minutes 1969

Spare Bedroom by Frans Zwartjes 15 minutes 1970

Standard Gauge by Morgan Fisher 35 minutes 1984

“A kind of autobiography of its maker; a kind of history of the institution of whose shards it is composed; the commercial motion picture industry. A mutual interrogation between 35mm and 16mm, the gauge of Hollywood and the gauge of the amateur and independent.” (MF) “a repository of abandoned footage in which the blunt description of an industry standard flows into profound musings on the film industry and the ruthlessness of change. Defunct television episodes, ‘China girls’, glorious frames that resemble El Lissitzky and Mark Rothko paintings, Jean-Luc Godard, Roger Corman, Edgar G Ulmer and Leonard Kastle combine to illustrate a metaphorical biography of the history of film and a partial autobiography of Fisher himself.” (Tate Museum) “In Standard Gauge, the physical body of film scraps is the object to be massaged for its stories. Morgan Fisher handles each one for the camera and unfolds their scarred surfaces the story of the film industry, the practices embedded physically in aspects that movies usually ignore: the volatile history of nitrate, the ideology of color embodied by the China Girl, the tradeoff of sensuousness for economy in the abandonment of the imbibition dye process, and his own uneven career as a Hollywood editor. Before the movies represent stories, they embody another story, the back story of the industry and the people who work in it. This was Fisher’s last film; after that he started doing the same thing with painting…” (Laura Marks)

Frans Zwartjes

“Frans Zwartjes (Alkmaar, 1927) is a filmmaker, musician, violin maker, draughtsman, painter and sculptor. In the late sixties he causes a furor with artistic black-and-white films in which heavily made up and over-dressed actors (such as the performance artist Moniek Toebosch) are caught in a web of sexually loaded power games; hysteria, psychosis and cruelty are among his regular themes. The oeuvre of Zwartjes, once called “the most important experimental filmmaker of his time” by the American essayist Susan Sontag, includes over fifty films.

Artist and Teacher

In 1968 Zwartjes was one of the first Dutch visual artists to make use of film: initially as a record of his performances, but quite soon after as an independent medium, perfectly suited to his way of creating visual art. Zwartjes did everything himself: camera, sound, editing and even the developing in the laboratory. He would work with non-professional actors among his friends, and filmed in and around his own house. What he really preferred was editing his film “in the camera,” by switching the camera on and off while shooting. “My own motor system determined the film style,” Zwartjes stated in an interview. “It never occurred to me to wonder: can this shot follow on after this one? If you start wondering about that you should be looking for another job straight away.” At the Vrije Academie in The Hague, where he started teaching in 1971, and at the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, Zwartjes wsa regarded as an extremely liberal teacher who seldom prescribed his students exactly what to do. Almost without exception his ex-students call him a major influence on their development.” (Simona Monizza)

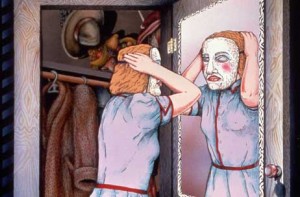

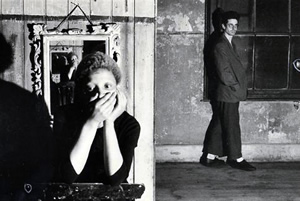

Bedsitters by Frans Zwartjes 18 minutes 1974

Bedsitters is set on the landing and the stairs of Zwartjes’ new house, then still empty, in The Hague. The filmmaker suggests a mysterious and complex space by using a ‘floating’ camera to film a number of crawling, creeping personages. Even when Zwartjes is in the picture himself, the camera keeps floating. The flowing movement and the impressive wise-angle lens turn the house into a buildling that resists logic. It seems, as in a modern computer game, to have several levels. Strange characters in sunglasses or masks run around on a landing and stairs of a house like explorers in a strange landscape, opening doors, doing strange things in the bathroom, attempting to enter closets and peek into doors. The camera twists and turns, converting the house into an impossibility. With Armand Perrenet, Moniek Toebosch and Trix Zwartjes.

Eating by Frans Zwartjes 10 minutes 1969

Three women chew themselves into a solipsistic fury while the camera looks on in his place. Processed into a silvery sheen by the filmmaker.

Spare Bedroom by Frans Zwartjes 15 minutes 1970

International prize-winning film from Zwartjes’ series Home Sweet Home , with Moniek Toebosch and Christian Manders as two somber personages who are engaged in a claustrophobic game of attraction and repulsion. “I film about me,” Zwartjes said once in an interview, “Me and the world, me and its relationships… For all sorts of reasons it remains a mystery.” Toebosch on the filming of Spare Bedroom: “Everything was brewing, it was very wonderful, but also very hard work.”

Program Four

Asparagus by Susan Pitt 10 minutes 1979

Baby Green by Ross McLaren 10 minutes 1974

Thriller by Sally Potter 35 minutes 1979

Asparagus by Susan Pitt 10 minutes 1979

Asparagus by Susan Pitt 10 minutes 1979

Asparagus is the now classic film that secured Pitt’s reputation as a major American animator. After taking four years to make, Asparagus, completed in 1979, won awards around the world, including First Prize at the Oberhausen Film Festival in Germany and awards at Ann Arbor, Baltimore and Atlanta Film Festivals in the US. Designed like a Pandora’s box, the film opens up the depth of Pitt’s own inner psyche, merging sensual and surrealistic imagery in the form of a Freudian dream. Focusing on erotic metaphors and intellectual references, she makes this matted-cel work a visionary masterpiece. “Pitt’s accomplished and imaginative effort, employing both full-cel animation and three-dimensional sets (including a ten-foot-lng theatre interior containing two hundred puppet figures in the audience), takes as its subject mattr a female magician’s relation to her art, daringly visualized as asparagus turds or wand-like phalluses. (Midnight Movies by Jonathan Rosenbaum and Jim Hoberman)

Baby Green by Ross McLaren 10 minutes 1974

A penetration of the veil which separates ordinary life from the hidden world of sensuality. (John Bentley Mays) Baby Green reveals the underlying polymorphous desires which men suppress in their social construction of heterosexual identities. (Dot Tuer)

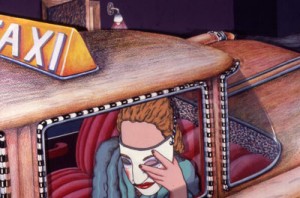

Thriller by Sally Potter 35 minutes 1979

Sally Potter’s rewriting of Puccini’s opera, La Bohéme , has become a classic in feminist film theory. A model for the deconstruction of the Hollywood film, Thriller turns the conventional role of women as romantic victims in fiction on its head. Mimi, the seamstress heroine of the opera who must die before the curtain goes down, decides to investigate the reasons for her death. In doing so, she begins to explore the dichotomy which separates her from the opera’s other female character, the “bad girl” Musetta.

As rich in sounds and imagery as it is theoretically compelling, Thriller provides the female spectator with a long-awaited recognition of her version of the story. What happens after the curtain falls on the death of Mimi, tragic heroine of Puccini’s La Bohème? In Thriller, Mimi teams up with the opera’s comic heroine Musetta to investigate her own death. Using Psycho strings, Marxist theory and men in tutus, the film asks whether the Bohemian artists upstairs are complicit in Mimi’s poverty, isolation and death. The film tells the story of the opera through three times: first following Puccini’s ‘script,’ second looking at the relationships between the characters and lastly by placing Mimi in context as a working-class woman. In the film’s only moment of synchronised sound, Colette Laffont (as Musetta) reads French theory, looking for the cause of her oppression, as Rose English (as Mimi) tries to attract her attention – and gets carried out of the room by the male artists. A witty and inventive voice-over delivered by Laffont threads together two sets of black-and-white archival images – of women workers and of classic stagings at the Royal Opera House – intercut into the high-contrast black-and-white still and moving images of four actors performing fragments and parodies of scenes from the opera in a bare room. Potter’s background in performance art and contemporary dance shines through in the eloquent gestural language in the film’s mainly still shots, while the tense investigation – shot through with humour – suggests the narrative pleasures of her later feature films.