.jpg)

- Songs flyer (pdf)

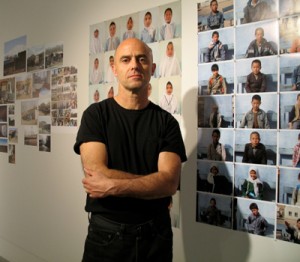

This is the commonplace, the tried and truism: that history is made by the victors. But in the cinema there remain a thousand plateaus of resistance, of those who can find their way through the camouflage of official versions and uncover new pictures or complicate old ones. Jayce Salloum has forged a distinctive practice that attempts to grant pictures to a political underclass, to peoples made invisible through military means and political marginalizations. Whether it is the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon or First Nations people in the Okanagan, he holds up not only his own frame, but the frames of those who have gone before. These frames can appear as maps, slogans, home movies, or even the lines of a face. His work invites us to shuttle between these different picture modes so that we might produce our own engaged readings.

This program of international documentaries was selected to bridge and parallel the exhibitions of Jayce Salloum at the Kenderdine and Mendel Art Galleries. Each of these movies have obvious and necessary relations to Jayce’s practice, though each takes a singular approach. The series begins with the work of master Chilean filmmaker Patricio Guzman, a Cannes-award winning giant who has made legendary films since the late 1960s. While his work initially appears to be a lyrical exposition of Chilean astronomers, it slowly turns its focus into the desert where regime protestors were buried. This is a movie about looking, about a search that will never end, and this restless inquisition is at the heart of Salloum’s approach as well. There is never a sense that a conclusion will arrive, that a definitive prognosis, a final certainty, will appear. Instead, we are met by a complicating network of signs, in this instance, a duet of outer and inner space, the resistance movement of memory, and a nearly unbearable beauty.

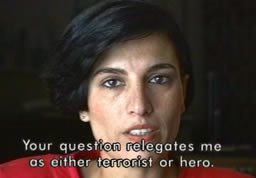

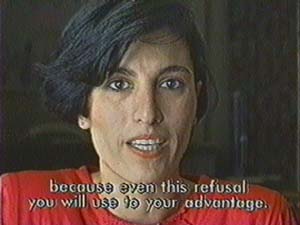

In The Oath, Oscar nominee Laura Poitras weighs in with an intimate portrait of an Al Qaeda insider Abu Jandal. In its first-person focus it is reminiscent of Salloum’s extended conversation with Soha Bechara in untitled part 1: everything and nothing. In both instances these iconic figures appear as types, larger than life heroes of the resistance, or on the other hand as deluded fanatics, tragically misdirected. How is it possible to part the veils of certainty that shadow these encounters? Derrida says that ethics begins by allowing the other to speak in their own language, and in both these movies the subjects hold forth at length, laying down cross currents of impressions that surprise and inform in equal measure.

Early in his practice, Salloum showed himself to be the maestro of the meta movie, a movie that rigorously unpacks its own looking and assumptions. Like the radical psychiatry of the 1960s that brought patient, doctor and hospital together into the same frame, or the Brecht-inspired tactics of Godard (“I need to show, and to show myself showing”), in his first long movie about Lebanon Up to the South, Salloum illuminates the frame again and again in a brilliant cross-cutting gesture that illuminates both sides of the camera. This meta-cinema found a new champion this year in Christian Von Borries who made the stunning essay The Dubai In Me. Filled with lavish, three dimensional modeling, and stunning high definition views, the director’s notes about the movie might have been written by Salloum about his own practice, “This film is searching for a new topography. This film is a metaphor, a displacement, a shift where territories are marked, where things are seen, where they are given names and meaning. In this sense, the metaphoric task of cinema can be seen as subverting a previous metaphorical order, namely the official mapping of space and time. An order that defines places, that defines what has to be seen and done in those places, the way they are inhabited, their capacities and incapacities… We have to reframe our community beyond the official scenarios about the third world, emerging countries, neo-colonialism, liberalization, modernization, etc.”

Six years in the making, Lessons of the Blood by James T. Hong and Yin-Ju Chen (they are husband and wife) offers a mix of styles, from direct reportage to media collage, in order to ravel out the largely suppressed story of Japanese biological warfare in China. In its multi-headed approach, it is distinctly reminiscent of Salloum’s work, which always seeks multiple points of entry and address, in order to establish a field of associations. It is this field that the viewer is invited to traverse, each in their own way, whether in Salloum’s wall photo collages or in audio-visual texts like Introduction to the End of An Argument. Lessons opens with a quote that might have headed up End of an Argument: “History is complicated. Nations are complicated. The political is complicated. Suffering is not.” If Lesson’s media collages are reminiscent of End of an Argument, or the found footage scrapbooks of This is Not Beirut, then the incisive details of the suffering, its locality, the bodies of suffering, bring an undeniable power and gravity to Hong/Chen’s movie. In the same way that the first person testimonies of torture ring through Salloum/Ra’ad’s Up to The South, Lessons visits Chinese villagers still suffering from bodily sores festering decades after the initial biological infestation. Hong notes: “I think for us in the west, to live like that would be like a living death. They just persevere. It’s something I suppose I couldn’t do. The other important thing I realized was that some of [the victims] didn’t even know what had happened [to them]. They didn’t know why they’ve had these horrible wounds for so many years.”

48 by Susana de Sousa Dias is a work of portraiture drawn from a single archive, and the notion of the archive is also central to Salloum’s work, which is often presented as a sprawling, necessarily fragmentary, overcrowded gathering of impressions, moving and still pictures, testimonies and reflections. It is both too much and not enough. Like a lover who has spent too long away, these presentations overflow with information, one story and point of contact leading to the next. The archive is partial, subjective, generous and beckoning. Won’t you have a look?

A pair of familial works by Richard Fung and Yu Gu are also reliant on archives, as each of these artists rub their personal stories into official histories. There is a shuttling, back and forthness in this work, as if one were seeing a detail of a face, and then an entire country that this face looks out at, and then again the detail. This shuttling relocates the global in the local, like the “wrong” bird sounds used by John Huston in Richard’s movie, or the defeated phone call by Yu Gu’s father who agrees to leave China immediately in which one can read the crushed hopes of generations.

“Beauty is a form of nourishment, if there was a Canadian Food Guide which listed the five essential ingredients to live, it would have to be included. I’m not talking about conventional attitudes of beauty but a richness and complexity of life, incomprehensible to a large degree, but very rewarding.” Jayce Salloum

1. Nostalgia For the Light by Patricio Guzman 90 minutes 35mm 2010

2. The Oath by Laura Poitras 96 minutes digibeta 2010

3. The Dubai In Me by Christian Von Borries 83 minutes HD Cam 2010

4. Lessons of the Blood by James T. Hong and Yin-Ju Chen 105 minutes 2010

5. Invisible Faces

Waterworx (A Clear Day and No Memories) by Rick Hancox 6 minutes 16mm 1982

48 by Susana de Sousa Dias 50 minutes 2010

6. Memory Islands

Islands by Richard Fung 8:45 minutes beta sp 2002

A Moth In Spring by Yu Gu 26 minutes 2009

La Jetée by Chris Marker 28 minutes 1962

7. Jayce Salloum: Once You’ve Got the Gun

This is Not Beirut (There Was and There Was Not) by Jayce Salloum 48 minutes beta sp 1994

Up the South (10 minute excerpt) by Jayce Salloum and Wallid Ra’ad 60 minutes beta sp 1993

1. Nostalgia For the Light by Patricio Guzman 90 minutes 35mm 2010

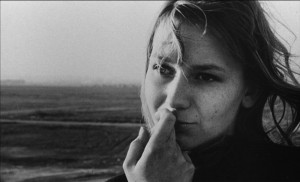

How much better the world appears when one can look over the shoulder of a fine cinematographer. Beauty lies waiting to be uncovered in every corner, it’s just a question of time, the time it takes to set up a shot, to establish a position, a frame from which to begin noticing where the light is falling. Four minutes float past without a word spoken, right off the top of the movie, and when at last language enters the room, the speaker is nowhere to be seen, instead, a series of glowing nostalgia shots offer us views of home as it might have been, pressed under glass like specimens.

“The astronomers created an enormous telescope to bring two seemingly incompatible things closer: the origins of everything and the past of everything we are today.”

Celestial seasons mingle with petroglyph journeys carved out into desert rocks. Why Chile I wonder? Is it true, as the old world voice-over poetically intones, that these skies were kissed by the Gods? The dry climate appears ideal for finding traces of the earth’s past, while the skies are clear enough to grant views of light so distant that these stars have already died before they reach the eye of the telescope.

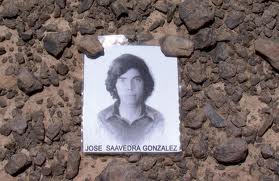

Beneath the cinematographer’s glassy stare, the spoons dance, the train flows through the Atacama desert, the Indigeneous worker graves lie windswept and abandoned on the high desert plain, and the concentration camp victims of Pinochet are gilded in star dust. Women sift through the desert sand, looking for the remains of those they have lost. Like all beauty, this one is heartbreaking, sometimes unbearable, even at the stately distances this camera is most comfortable with.

“What did you find of your brother?”

“A foot. It was still in his shoe. Some of his teeth. I found part of his forehead, his nose, nearly all of the left side of his skull. The bit behind the ear with a bullet mark. The bullet came out here.”

This is the terrible poetry of memory. Filled always with necessary returns, these survivors speak out against the repressions of Chile’s feared dictator and the police that are always ready, in country after country, to say yes to power. Thousand were punished, kidnapped and tortured and buried in mass graves here in the desert. Many of these graves were dug up by the regime and bulldozed into the ocean, but these excavations occasionally left spillage, evidence and grief memorials for the ones who escaped the death squads. These sunburnt survivors insist on speaking their unbearable truths, dedicating their lives to searching, and bringing their evidence forward so that the magicians of cinema will offer one last conjuring trick, and let these memories live.

2. The Oath by Laura Poitras 96 minutes 2010

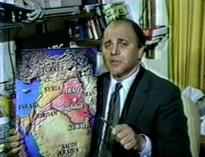

The handsome taxi driver is Abu Jandal, former bodyguard of Osama Bin Laden. I keep waiting for his eyes to flash, whenever they fix on someone they light up like a sports stadium, and then he smiles. Again and again. He levers open a coke while decrying American imperialism, gets his young son up to pray in the morning, but when his young boy insists, the news gives way to cartoons which only makes his young jihadi-in-waiting long for the toys he sees in such abundant display. What does a revolutionary do when he is no longer part of the movement? Raise a child, drive a cab, worry about food and money. He was once on the front line, he tells the filmmaker, but now he worries that someone will kidnap or kill him. He has to work hard for little money, everything is insecure, and he is plagued by insomnia. It’s not easy being the ex-emir of hospitality.

His brother-in-law is Salim Hamdan, bin Laden’s driver, and the first Guantanamo Bay prisoner to be tried by American’s one-sided military tribunals. The shadow of torture and years of windowless detention hang over this movie, even as we are led through the show trial stagings of the imperium. A country can feel so heavy when it’s resting on your head.

“America can’t fight without planes, girlfriends, pizza and macaroni. But our jihadis can live on stale bread.”

How unusual that the faraway regimes that America is used to crushing underfoot and handing over to the nearest available dictator, is actually fighting back. This sensitive, intimately made portrait movie shows some of the cost of that resistance, via news clips, and Guantanamo asides, and time with Jamal above all, time to lay down a series of positions and let them float alongside each other, in all their glowing, glittering, impoverished light.

What is remarkable about this movie is that these Arab men are actually allowed a voice. They can speak for themselves, as if they were as real as white people. An act of equivalence which the mainstream media has yet to permit. Instead of cowering beneath slogans or received ideas, this movie offers a duet of the working poor who arrive in all their contradictions and tragic hopes. Shorn of types and soundbytes and screaming headlines. As if we were neighbours.

3. The Dubai In Me by Christian Von Borries 83 minutes HD Cam 2010

A rigorous and relentless self-examination underscores this cine essay on the marketplace projection of Dubai. Offering Second Life avatars and Michael Jackson moonwalks as political choreography precursors, the filmmaker shows a hyper-capitalized feudalism. In his hands, Dubai is both a state and a state of mind, it appears behind the camera in terms of gear choices and tripod height, and in front of it as a migratory global underclass of workers who are forever busy offstage. Between the weightless simulations of a city scrubbed clean of its inhabitants – where there is nothing left but the commodification of space – are panoramic postcard views of trucks filled with shit, or hijabbed tourists clutching their shopping dreams. Every picture is framed, and every frame is announced, remarked upon, unpacked. All the money that dreams can buy might be found here, in the twelve hour days of the serving staffs, their passports confiscated, their plane fares recharged at rates that would bring smiles to any loan shark. Like every utopia, the poor will be made to pay for this promised land of new Islamic capitalisms. As the filmmaker remarks, occasionally, between the sustained views of a world that is already a picture, “Global identities laundered here… for those who can afford it.”

4. Lessons of the Blood by James T. Hong and Yin-Ju Chen 105 minutes 2010

This hysterical history lesson offers up a smorgasbord of industrial film clips, televisual excess, Olympic triumphs, and poison gas victim testimonies. Heated up with martial music and a sometimes delirious collage, its restless intelligence offers peekaboo glimpses of Japanese history . Meanwhile in China, survivors of Japanese biological attacks during the second world war offer their broken faces, their burned and miscoloured ankles, to show the effects of the poison gas, even all these years later. They have grown into these damaged bodies. This biological warfare is going on today, carried forward in their daily struggles. And still the Japanese government insists it never happened.

The Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Corps, established by the Japanese in China, was the centre of their biological warfare. The remains of buildings dedicated to frostbite experimentation (because of the anticipated Russian invasion) are waiting to be named. Test subjects were frozen and thawed, people were hung upside down to see how long it would take them to die, some choked to death in order to study asphyxiation. Bacterias were injected, and food laced with anthrax was served, all observed by scientists as their test subjects slowly died. Dissections occurred before inmates expired, so that internal organs could be examined. Deadly bio strains were harvested from barely living subjects cross-bred for maximum strength so that enemy food supplies could be poisoned. And how could these plagues be delivered to enemy populations? Rats were bred and infected with poisons. But when war ended, the biological units in China were ordered destroyed, and all of the prisoners were executed and burned. Though traces still remain. For decades this human experimentation data was sealed and protected by the United States government.

As the movie progresses, it finds its way, it has so much to tell, about the secret war criminals for instance, the repression of the Nanjing massacre and the cult of the war dead in Japan. “Here there are no war criminals, only war heroes. Some of whom massacred and raped civilians, tortured POWs, and murdered slaves. Even animals that served the emperor get their due.”

The filmmakers show us how history has been scrubbed clean of its atrocities, its victims rendered silent, its dissidents corralled and excluded. State museums demonstrate that every Japanese war was conducted in self defense, and how they aided liberation struggles abroad, inspiring, amongst others, Ghandi in India. The only victims of war since time began have been the Japanese.

Meanwhile, after the 1942 bombing of Tokyo by 16 American planes, the carriers were too low on fuel to make it back to the carriers, and crash landed in China. They were taken care of by Chinese peasants, and in retaliation, the Japanese army killed 1/4 million people, and instituted widespread biological warfare in Zhejiang Province. The survivors can’t heal, but lived while everyone in their families died. “These people are unique in the sense that their own bodies have responded to the germs causing the ulcers, the rotten leg syndrome, and have worked out a relationship where the germs can’t kill them but their bodies can’t heal.” They’re poor, and many can’t afford medications. Because the Japanese refuse to acknowledge they engaged in biological warfare, there is neither recognition or compensation. They have been left behind to await amputations or death. What a long war it has turned out to be. Like every war.

5. Invisible Faces

Waterworx (A Clear Day and No Memories) by Rick Hancox 6 minutes 1982

48 by Susana de Sousa Dias 50 minutes 2010

Waterworx (A Clear Day and No Memories) by Rick Hancox 6 minutes 1982

Canada’s most influential home movie maker revisits a golden palace when he is at last old enough to be young again, and shoots only what he can’t see. The entire film occurs twice, like a round dance of memory, the second time with the addition of computer titles that re-animate these storehouses of recall. There is a ghost in every frame, along with a loss that hosts no regret.

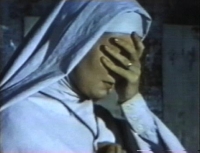

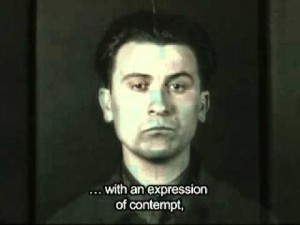

48 by Susana de Sousa Dias 50 minutes 2010

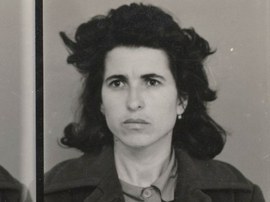

Every image in this film was made by a criminal wearing a cop uniform, culled from the secret detention archives of Portugal’s police. Every one of them shows a turning point, a confrontation of power, a decisive moment. The filmmaker seeks out these survivors today, and they tell their simple complicated stories, of their torture and disfigurement and survival, in other words, they show me the cost of having a face, the cost of seeing a face like this one. So in place of a face lined with its terrifying memory marks, there are photographs, floating up out of the darkness, staring back relentlessly, pouring words out of their asymmetries, reflecting on their time inside. And in this divide between an old photograph and a present day testimony, there is room enough for an audience to bear witness, to accompany the time it takes to speak against the law.

The pictures show their subjects in profile and from the front. They are state pictures, taken by the dreaded PIDE (political police) during the 48 years of Salazar’s dictatorship, from 1926-1974.

“I ended up living for everybody else,” the first photographed woman tells the filmmaker, her breath and pauses and swallows as much a part of her diction as any testimonial aside. Her photographs hardly able to bear the light of looking. Not after all those years in detention. Another says, “From me, they did not get the pleasure of seeing a tortured face.” There is no hint of triumph in his voice, no sense that there is even the possibility of victory left. But there remains something in him untouched and unmoved by his years of abuse, and I can’t imagine it, he speaks from the other side of the world. How much of his feeling he must have had to shut away in order to maintain this small hope for himself, what kind of effort to maintain the vigil of his dignity. The possibility that this dictatorship would not take root everywhere in his body, that some part of him would resist, some small spark, and from that spark, one day, the entire government would crumble. And it did. Though they were arrested by the thousands, night after night. “After eighteen days of not sleeping, how can a heart keep beating?” one asks, but it does. It survives, even when he has been carried too far. One of them finds a moment of their own empowerment even in the act of having his picture taken, “The face is what you decide.” And of course not providing information to the police. Outside prison, it was difficult to keep state repressions out of everyday conversations, there were things that could and couldn’t be said, and worn and looked at. And sexually, as one former inmate describes, “It’s as if we had no hands.” The body and the body politic. The liberation, the way out, to defeat a regime where there were no longer children (“We were all old, we were all the same age, wearing the same clothes”) it was necessary to begin with each sentence, with each encounter, with the testimonies on offer here, for instance.

6. Memory Islands

Islands by Richard Fung 8:45 minutes 2002

A Moth In Spring by Yu Gu 26 minutes 2009

La Jetée by Chris Marker 28 minutes 1962

Islands by Richard Fung 8:45 minutes 2002

Fung offers a winning deconstruction of John Huston’s Heaven Knows Mr. Allison, filmed in Tobago in 1956. The artist’s Uncle Clive is an extra, playing a Japanese soldier, though he doesn’t look Japanese, nor has he ever seen anyone from Japan. No matter. In a clever series of intertitles and reframings, Fung turns the background of Huston’s film into the foreground, offering details of his uncle’s life and recounts the swap of 12,000 acres of Trinidad for 50 US warships. Here the movies appear as an extension of war, as the usual romantic veils are brought down over the bloodied imperial reach. As background turns into foreground, nocturnal animals appear in daylight, and the unheard stories of history’s supporting cast can at last assert itself.

A Moth In Spring by Yu Gu 26 minutes 2009

It might have been named: embrace your failure. The artist returns to her hometown of Chongquing in China where she grew up in order to shoot a dramatic movie. But word leaks, the neighbours are talking, and soon the authorities arrive to shut the whole dream down. In a stunning parallel narrative, the filmmaker is forced to return to her parent’s own dissident roots, and weaves a powerful generational duet that talks about art and the student movement in 1989. Instead of a dramatic turn, this lyrical hybrid, leaking accidents and unforeseen moments, opens its crushed heart to every unguarded face in the room, the looks of stunned disappointment, tearful departures, family admonitions. The continuity of political repression and the failure of the planned document, which appears in script writing intertitles, provides the means for an embrace of what is actually happening, a generosity rare in the cinema.

“In the four months of living in Chongqing, there were times I felt like an alien from outer space. Leaving the cradle of Hollywood, a sense of reality set in. Unlike Beijing or Shanghai, Chongqing has no pre-existing infrastructure for filmmaking. There was no casting service, no film labs and no real equipment houses. My cinematographer Adam and I had to think of other alternatives fast. Then I realized that I wanted to make something closer to a documentary. Not in the sense of using a cinema verité camera style or purposeful jump cuts. Instead, I wanted to document the free spirit that still glimmered in this art school despite the perpetual tearing down of the old city, despite the onset of unbridled materialism, despite the government’s insidious indoctrination. I wanted to make a story that paid respect to my family history, one of survival of dreams despite repression. I imagined, too, that this story was not uncommon among people around the world. I discarded casting options from entertainment agencies and instead asked friends and acquaintances to act in my film.”

La Jetée by Chris Marker 28 minutes 1962

A science fiction tour-de-force by cinema’s most mysterious filmmaker. If he had made only this movie he would still be considered as one of cinema’s most prized talents. A sharply drawn story narrated almost exclusively in photographs, only one shot appears in motion. Conjuring entire worlds with a few well placed shadows and an incisive montage, Marker takes the viewer on a deeply engaging trek into a future dystopia, riding inside the mind of a time traveler whose intergenerational love story leads him fatefully towards a dizzying climax in the Orly airport.

7. Jayce Salloum: Once You’ve Got the Gun

This is Not Beirut (There Was and There Was Not) by Jayce Salloum 48 minutes 1994

Up to the South (Taleen a Junuub) by Jayce Salloum and Walid Ra’ad (20 minute excerpt of 60 minute videotape) 1993

This is Not Beirut (There Was and There Was Not) by Jayce Salloum 48 minutes 1994

The artist’s establishing shot offers us books and television pictures and a tourist’s home movies made in Lebanon. He says that many things preclude his arrival in Lebanon, primarily the difficulty of finding it. And by “it” he means the postcards, the rumours, the breaking news, the music, oh yes, the whole sum of cultural camouflages that a visitor, and for that matter even the residents themselves, will drag into the country with them, and insist on looking through, no matter what evidence might present itself to the contrary. The artist offers up a collection of borrowed views and clips offering Beirut as heaven and hell, vacation getaway and war zone. In other words, Lebanon appears as a media phantasm, a ghostly projection of empires past and present, and Salloum is canny enough to implicate not only his own looking, but the looking of the viewer. How else can we see what we see, except through this scrim of projections that are already in place before arriving?

A long and intermittent debate with Walid Ra’ad runs along the spine of the movie, talking about “the project” of giving Lebanese artists camera so that they can make their own pictures. And the project of making their own pictures in a simulacrum that is only too real. What does it mean to be a citizen of this country, and does a lifetime of looking out on these streets, these hills, loosen the grip of the media mirages that have settled on everything here like ghost powder?

“To Lebanize a land came to mean to destroy it from within.” Robert Fisk

Salloum’s casually brilliant shooting insistently grazes away from traditional framings, seeking out startling juxtapositions that set off new trajectories of thought, often fleeing any ability of the speaker to command and contain their subjects. The accumulation of scenes are not designed to advance a single argument, to come to a point, but to produce knowledges. To provide a “representation of representations.” In a suddenly erupting philosophical dialogue carried out while trekking the remains of another rubble strewn building, he learns that there is no word in Arabic for “representation.” It’s as if the absence of this idea were responsible for the destruction they are stepping through, the endless bloodshed and ruined lives.

Up to the South (Taleen a Junuub) by Jayce Salloum and Walid Ra’ad (20 minute excerpt of 60 minute videotape) 1993

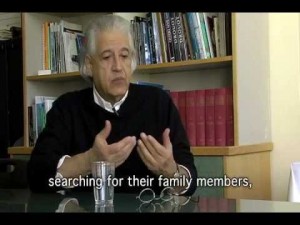

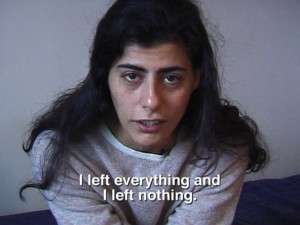

While the Israeli state was established in 1948, Palestinians were being hunted down and killed or expelled. Many fled to Lebanon (and Jordan and…), and after a series of cross-border attacks from both sides, the Israelis invaded Lebanon in 1978 and again in 1982, when they occupied southern Lebanon. They withdrew in 2000. Ra’ad and Salloum weigh in on the occupation and its resistance, stopping along the way to offer thoughts about the impossibility of presenting these pictures, these testimonials, to the West.

This twenty minute excerpt begins with a suite of articulate speakers who recount moments of their detention, and the relentless and systematic torture they endured in Khiyam, the dreaded political detention centre in southern Lebanon run by the Israelis. Incredibly, after years of whippings and beatings, they can still come up with statements like this one: “Well this detention taught me more about the enemy, I mean the enemy you knew from afar. You get to meet them face to face, you know them up close. Because some folks went in there with no idea about Israeli practices. But after you come out you are fully aware, and more then ever convinced of the need to resist.” After the testimonies, another voice enters to reframe the dialogues, French-speaking historian/philosopher Roger Assaf, who adds another layer to this palimpsest of reflections. “But to defend myself I have to become someone else, and thus I risk losing myself… What does it mean to resist? The one who resists is the one who does not let go of something he holds dear. This is why the most formidable form of resistance in south Lebanon today is the fact that most people are staying there, staying put. Their homes are destroyed but they try to work and to cultivate their lands… And without this form of resistance, there is no resistance.”

Salloum and Ra’ad’s meta-witnessing is as powerful and relevant today as it was when it was made more than fifteen years ago. With an uncanny tact and delicacy they create a dense mosaic of voices, broken architectures, out of the car window landscapes, all framed and reframed by their ongoing dialogues on representation. There are some people so shining and fine they have been named as model citizens. Here is a model movie, an example of a deeply engaged ethical movie practice unafraid to show both sides of the camera.