1. Franci Duran: Poetry of Exile

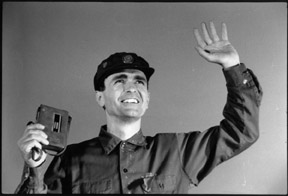

2. Steve Sanguedolce: Documentary Paintbrush

3. Lesley Loksi Chan: The Storyteller

4. Ali Kazimi: Crossing Mountains

5. What Sweetness Lingers (Richard Fung, Ali Kazimi, John Greyson)

6. Istvan Kantor: The Deadly Gift of Neoism

7. Istvan Kantor: Spectacle of Noise

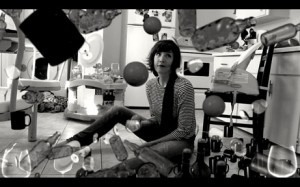

8. Jenn E. Norton and Kika Thorne: Girl Gang

1. Franci Duran: Poetry of Exile

She arrived in Canada on the first plane of refugees after the CIA-backed assassination of Chile’s democratically elected Salvador Allende. In Chile this day is remembered as 9-11. This primal wound and displacement lies at the heart of Duran’s making, whether it means lifting a camera to see a rainy street, a mountain or the face of her young boy as if she’d never seen before, or taking aim at the dictator who has ruled Chile in the years of her maturity. Roughly speaking, her work may be divided into three central areas of interest, the first is an extension of the home movie, looking at the birth of her first born, or her own childhood. The second looks at Chile under the rule of Pinochet’s dictatorship. While the third is more broadly interested in questions of the archive and historical records and technologies. Hegel wrote: History is what man does with death. But there is a last flicker before the end, call it magic hour, the epitaph, the closing song, and the fragile beauty of this passing draws this artist toward it again and again.

Boy 5 minutes 2005

What does it look like at the beginning? The first time he ever saw a table, the large foot of an adult stepping towards him, a window opening like a heart. Duran offers us rainy moments of Vancouver as an accompaniment to the birth of her first child. A slowly moving hail of abstract nights lights precedes a slow motion birth, recoloured and rephotographed from a TV screen. The artist’s voice offers up a series of dates along with the facts that accompany them, her son’s favourite book, animal and word (No). Each instance of looking arrives in fragments, there is no story to pull it all together, unless it is the story of memory itself, with its necessary omissions, its shorn away pieces and left-overs. The formal experimentalisms and material fetishes that inform this movie appear here as an analogue for memory itself, an inheritance of seeing in the dark. It makes me wonder: is every film the mother of its audience?

Cuentos de Mi Ninez (Tales from My Childhood) 9 minutes 1991

Salvador Allende was elected president of Chile in 1970 and began a series of reforms that included government control of education and health care, the nationalization of copper mining and banking, and a continuation of land redistribution to peasant farmers. His government was overthrown by a CIA-backed coup on the orders of American president Richard Nixon in 1973, and was replaced by the army general Augusto Pinochet. This harsh authoritarian rule resulted in thousands of death and systematic torture (including women and children). Duran recounts the historical record against pictures of the childhood she had and never had, the innocence lost and found, and her refugee flight to the safety of far away Canada.

Dominion 2:48 minutes 2004

Princess Diana flickers back into life again against a hazy video palette in images drawn from a CNN tribute entitled “The People’s Princess.”

Retrato Oficial (Official Portrait) 1 minute 2003

“My focus on the artifact is linked to my own early childhood and my family’s exile. I came to Canada as a refugee at the age of six, but have very few tangible memories of that time. Since 2003 I have been working on a film series entitled Retrato Oficial (Official Portrait) which deals with the historical reach of the now-deceased military dictator Augusto Pinochet.”

In the first (and shortest) movie in this ongoing series, Duran offers us images of the Chilean dictator shortly after arriving back in his home country. He was indicted for human rights violations in 1998 by Spanish magistrate Baltasar Garzón and arrested in London. It was the first time that several European judges applied the principle of universal jurisdiction, declaring themselves competent to judge crimes committed by former heads of state, despite local amnesty laws. After having been placed under house arrest in Britain and initiating a judicial and public relations battle, Pinochet was eventually released in March 2000 on medical grounds by Home Secretary Jack Straw without facing trial. When he arrived back home in Chile, shortly after leaving the airplane, he got up out of his wheelchair and walked, demonstrating to one and all that claims of his ill health were at least premature.

Retrato Oficial (Official Portrait) 4:10 minutes 2009

Duran begins with a political fable: imagine a country which permits only a single picture: a full length portrait of its ruler. Copies can be made, details enlarged, but no deviations are permitted. As Benjamin famously remarked, facism aestheticizes politics, while communism politicizes aesthetics. Duran’s surveillance myth of a picture that looks back from each artist’s hand resolves in the first broadcast of Pinochet immediately following the coup, in which he suspends the parliament and the courts. Duran’s material concerns seem to wrestle with the dictator that lives inside her fingers, as if the body and the body politic were the same somehow, as if it were necessary to oppose the decades-long military occupation in Chile on every level, including the level of the material signifier, the film itself, newly grown and luxurious in her careful treatments.

Mr. Edison’s Ear 32 minutes 2008

The artist’s longest and most complex movie to date, Mr. Edison’s Ear is part Edison biography, part technology essay, turning around the deaf inventor of the phonograph. It is punctuated by multi-screen animations, moving text displays, and Edison’s own short subject movies that offer a rich tableau of circus performers, staged battle scenes and a child born away by a great black bird. These carefully excised moments are punctuated with interview briefs by a trio of media historians and archivists. Lisa Gitelman offers up this observation: “I think of the spoken voice in that period as the standard of ephemerality. It was the thing you couldn’t keep. Sure, you could have a newspaper reporter or stenographer try and write down what somebody said but there was really no keeping the voice. And with the phonograph there is. I don’t think people made a direct connection, that may have, on some deep symbolic level, offered a level of compensatory stability in a period of profound change. Amidst all the loss involved in social changes, cultural changes, and economic changes, here is one moment that offers a preserve-ability, something to cling to.”

2. Steve Sanguedolce: Documentary Paintbrush

Three decades later he’s still at work in the man cave, lowering himself into every frame, getting lost in what he dare not even name as hope, and then finding the thread that will lead him to the movie that is already busy making itself. Every four or five years he releases another personal documentary, all shot with the same 16mm on-the-shoulder camera that were standard issue for news cameras news crews in the 60s, (modified from cine verité dad Pennebaker’s home-made adjustments). His work offers up survival testaments that speak of addiction, family and mental illness, often digging deep into the roots of impossible feelings and threshold experiences in order to ground them again in the experience of a singular body of light.

Blinding 72 min. 16mm/HDCAM SR, hand coloured, 5.1 surround, 2011

Blinding is the latest Sanguedolce opus, an epic turn into the act of seeing itself. He began by interviewing three unusuals: a blind man, a dyke cop, and a military pilot. Each account strips away layers of assumption and cliché – the shadow we cast on experiences before they occur – as layers of complication and contradiction swirl around these figments of a self. The peacekeeper who finds himself in the middle of a war. The lesbian who has to reach across sometimes homophobic superiors in order to find her way. The blind man who will never see his wife. In place of the usual illustrative accompaniments, the artist has dug into his own back catalog, and dished up an anthology of moments from his seeing, along with that of friends and familiars. All these have been hand-processed and coloured, granting the surface a seething, flickering material life, all set in a shimmering psychedelic haze. As usual, it is up to the viewer to piece together the trio’s insights and calamities, as the associative collage dreams by, filled with lovers past and future.

3. Lesley Loksi Chan: The Storyteller

One of the most important new voices in Canadian narrative cinema, Lesley Loksi Chan was born to make movies. Her genius is that she fully embraces, or so it seems, the place she actually is. No far away Telefilm dreams, no waiting for mountains of equipment, instead she crafts out of the circumstances of her own life an intimate, witty, thoughtful, touching cinema, often featuring her young boy and her sister as actors. Her whimsical dramas feature air tight voice-overs, exquisite framings and hand-made animations. Whether dishing a love story or leaning in close to hear the whispers that only a mother and son could exchange, Chan lights it all up with a breezy, sweatless gaze so fine you don’t notice the bullet holes in your eyes until you stagger out of the darkness and find everything changed.

Dear Sister 6 minutes 2005

A lighter than air, faux doc about the artist’s sister who turns out to be – no surprise here – a filmmaker. Her “almost award winning” titles include The Clock Haters and The Blind Microscope Makers of Macau. Adopting a slide show and tell format, her off the balance beam storytelling effortlessly draws together moments of a room, a blowing dress, the shadows of a fan, conjuring a universe of love, loss and family out of these simple materials.

My Matsura 11:22 minutes 2006

Despite the traditional emulsion scarring of the novice hand-processor the opening two minutes of this movie, were so perfect I forgot to breathe and had to be resuscitated. It’s a good thing there was a doctor in the house. The film’s second movement offers the photographs of Frank Matsura, taken in the early 20th century, as a way to read the photographer himself, looking back through the lens. The subtitled sentiments are so crisp and tender and necessary that for an instant Matsura flickers alive in front of me, and then he’s gone.

i no i no 11 minutes 2005

Five early shorts from this essential filmmaker’s treasure chest. The first offers what Gertrude Stein might have named “tender buttons.” Are these the sweet everythings that lovers say to each other? The ones stuck in their own mirrors, but who can’t help reciting their lines in company. This opening moment, drawn up in a single economical shot, and appearing nearly like animation, or at least choreography, sets the tone for the vignettes that follow. She re-voices the opening scene of The World of Suzie Wong, then delivers a harrowing series of assaults she titles My Best Rape So Far. She wraps each of her pointed shards in children’s materials and sprinkles them with magic dust so that these unbearable moments can be spoken and shared.

Wanda & Miles 13 minutes 2007

A mother and son duet that is as perfect as a dollhouse. Chan grants her lustrous home movie settings a faux mythic framework, he is the boy who scratches his head whenever he sees maps, she is the eye-patched single mom who carries her child in a suitcase until he outgrows it.

There are many in the fringe who are busy lensing material, but few can match the one-light precision of these pictures, made with a lyrical and gently moving camera that illuminates one detail blooming after another. Perhaps it’s because Chan is working with her son and sister, and so she can wait for the good light, or perhaps it is because she is busy shooting only in rooms she lives in, so she always knows when the good light will arrive. But her intimate framings and generous perspectives – occasionally punctuated by wonderfully crude animations or no-tech special effect flurries – grant a buoyancy to this story of loss and individuation.

Curse Cures 10:43 minutes 2009

A hand-made animation about the garment industry sweatshops that so many new Canadian immigrants worked in. Particularly women. It’s told from the inside out, with a few, iconographic pictures and a collection of acetate texts. The filmmaker’s hands hardly leave the screen, forever busy re-arranging new text lines or sweeping pictures out of the frame. “Should we be happy?” The luminous Astor Piazzolla lends his ear to the soundtrack. Love live analog filmmaking!

Compost Mon Amour (11:40 minutes 2006)

Possible lives accumulate in this elegantly framed meta-narrative. Once again Chan’s uncannily cinematic sense creates full blown scenes out of the most modest of materials. Playful and witty, every word in this voice-over driven romantic vigil is another perfect note, which the artist off-sets by having her mother read the whole thing. Another daring gambit that ensures a fine balance of charm and irony. It’s all so beautiful, so casually perfect, that it must have been a thousand kinds of work. So why does it feel like everything here has been made at recess?

4. Ali Kazimi: Crossing Mountains

Is there anyone in the fringe who is able to shoot into the light with the clarity and precision of Ali Kazimi? His father was a Kodak manager, so he has spent his entire life close to the image, in darkrooms and developing situations. Moving to Canada brought him an outsider’s vantage, and Shooting Indians was one of the first projects he undertook. After a year, the project crumbled in his fingers through no fault of his own, but like many of the very best artists, he was able to find in this catastrophe an opportunity, when he picked up the thread ten years later. Movies are a medium of time, but it is increasingly rare to find time located in the movie itself, in this moment of instant knock offs and digital fast food. Kazimi works slowly, waiting for the light, waiting for his subjects to come around, for the relational politics to gain a necessary depth. What a gift he is.

Shooting Indians: a Journey with Jeffrey Thomas by Ali Kazimi 56 minutes 1997

Ali Kazimi offers a duet of artist and subject in this beautifully made and award winning doc. Filled with gorgeous frames and a receptive accompaniment, the artist follows Jeffrey Thomas, the soft spoken, hard-hitting Iroquois photographer. Thomas’s project takes up the task of creating pictures of first nations people as they appear now, both in urban settings, and in ceremonial recall. But after a late night car crash, hospital staff whispered of his malingering, and neglected to treat what turned out to be a broken neck. The missed diagnosis left him in a state of lifelong pain, every limping step a reminder. This movie was begun when Ali was still a gold star film student, fresh faced from Delhi, and then picked up again ten years later. This luxury of time shows us the breadth of Thomas’s practice, as well as his deepening physical disability. The unseen father in this story is Edward Curtis, the turn of the century photographer who dedicated his life to making pictures of the “vanishing race” of American Indians. Initially dismissed by both Kazimi and Thomas alike as another anglo imperialist, they each make a turn, particularly as Thomas dredges the archives, and arrives at a more dimensional view, as they each work to place themselves as part of a complicating post-contact narrative. At last, purity has been left behind.

“The vanishing race has emerged from the shadows reborn, renewed and asserting its cultural survival. Aboriginal cultures, like all cultures including my own, have borrowed, incorporated and absorbed influences from all encounters, absorbing reviving and at times reinventing themselves. In the end what has vanished is my image of the authentic, imaginary, Red Indian.” (Ali Kazimi)

5. What Sweetness Lingers

What a rare and fine beauty occurs when social justice questions are rubbed against an artist’s singularity. No one does it better than Richard Fung, Ali Kazimi, or the irrepressible John Greyson. Friends and comrades, they have changed the face of media art in this country, bringing forward exquisite outsider articulations. Wayne Yung is part of this media harvest, a savvy queer now making his home in Germany.

Islands by Richard Fung 8:45 2002

Covered by John Greyson 14 minutes 2009

Rex vs Singh by Richard Fung, John Greyson and Ali Kazimi 29:38 minutes 2009

1000 Cumshots by Wayne Yung 1 minute 2003

Islands by Richard Fung 8:45 2002

Fung offers a winning deconstruction of John Huston’s Heaven Knows Mr. Allison, filmed in Tobago in 1956. The artist’s Uncle Clive is an extra, playing a Japanese soldier, though he doesn’t look Japanese, nor has he ever seen anyone from Japan. No matter. In a clever series of intertitles and reframings, Fung turns the background of Huston’s film into the foreground, offering details of his uncle’s life and recounts the swap of 12,000 acres of Trinidad for 50 US warships. Here the movies appear as an extension of war, as the usual romantic veils are brought down over the bloodied imperial reach. As background turns into foreground, nocturnal animals appear in daylight, and the unheard stories of history’s supporting cast can at last assert itself.

Covered by John Greyson 14 minutes 2009

Invited to attend the first queer festival in Saravejo, the artist finds himself in the midst of religious backlash and anti-queer hysterias. As usual Greyson answers the bell with a video camera that searches out the bored, hate-mongering teens in the afterlight, and the dedicated fest organizers on the other side, working in the face of death threats and organized intimidations. Using songbirds as a metaphor to lift these pictures of struggle, Greyson once again crafts a poetic and indelible response.

Rex vs Singh by Richard Fung, John Greyson and Ali Kazimi 29:38 minutes 2009

Three of Canada’s finest movie makers join hands in this four-part courtroom drama. Beginning with a transcript of a 1915 trial, a pair of Sikh mill workers are aggressively entrapped by undercover RCMP detectives who charge them with sodomy. As each artist offers a shifting perspective on these nation building cases, the history lesson makes clear how Canada’s most multicultural city (Vancouver) was strictly divided along racial lines, underlined by folks by the Asiatic Expulsion League. Is it really true that a boatload of Indian migrants could be turned away solely based on their birthplace? Each segment offers another prismatic view, summoning historians, musical riffs and textual revisits. Essential viewing.

1000 Cumshots by Wayne Yung 1 minute 2003

Trailer paced boy-on-boy action storms across the screen in this almost sexy frenzy. Welcome to the white party, chants the artist. So what’s changed exactly, after all these years? Porn as deconstruction, de-celebration, racial border line. Forever Yung.

6. Istvan Kantor: Bad Boy Revolutionary

The hardest working man in un-show business is a one man factory of impromptu performances, machine sex actions, paintings, pop tunes and hyperbolic video knots. Born in Budapest in 1949, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 marked him deeply, and is a moment that is recalled again and again in his work. In the 1970s he studied medicine, and at the same time hung out in Budapest’s fledgling underground art scene. He met mail artist David Zack at Art Club Budapest who encouraged him to move to North America, which he did in the early 1978. Since 1979 he has performed scores of “Blood Actions,” which has seen the artist extracting vials of his own blood and painting gallery walls (GIFT TO RAUSCHENBERG, blood-x, Ludwig Museum, Köln, Germany), canvases, street corners, newspapers. Many of these body art expositions have been unauthorized, and led to fines and arrests as the artist continues to listen to art with the whole body at once.

Kantor is the founder of Neoism, an art movement unquote whose primary embassy was Kantor’s Montreal apartment, an aperture that issued Situationist-like manifestos with a dizzying ironic fervour, an anti-consumerism zeal and Rentagon oppositional tactics. He organized a series of apartment festivals between 1980-88, 1997-2004. Following pronouncements of the death of the author he has renamed himself Monty Cantsin and Amen!, and encouraged others to do the same, proliferating viral identities in order to shatter the monad of self enclosure. Similarly his video work regularly features plundered and recirculated material mixed with his own shootings and complexly layered graphics. In 2004 he won the Governor General’s Award for Media Art.

Istvan Kantor 1: The Deadly Gift of Neoism

Revolutionary Song 9:15 minutes 2005

What is it about haircuts and cinema? A dread teen moment inspires this post-nostalgic revolutionary to reflect on fathers past and future, and leads him to sing it out loud. Candy coloured lyric swatches are laid over performative moments of the artist and video glitched piracies including generous glimpses of Godard’s fin-de-siecle Weekend. Everything burning and alive. Yes, it’s the same east European bludgeon at work, but now with tongue firmly planted in cheek. The end is the beginning.

Deadly Gift 14:35 minutes 2007

“The artist is just a toy… in the hands of the dominating forces. Silenced and re-animated. Imprisoned and awarded.” Part manifesto, part performance document, Kantor and company arrive naked at an Andy Warhol exhibit in the Art Gallery of Ontario, re-animate these too familiar paintings. Camped up against the backdrop of Warhol’s Red Disaster, the artists convulse and strike a pose, returning the body to its roots in dissent.

Accumulation 10 minutes 2000

The spectacle of noise and decay never felt so good. Still hooked on the shiny flypaper of your computer screen? No worries. This dance mix techno critique takes apart the society of spectacle in a series of staggered and staggering loops. The collapse of time, the co-optation of revolution and accumulation as the primary drive are drawn out in a delirious clip collage with sources ranging from Citizen Kane tantrums to John Carpenter’s glowing eye kids to post-war liberation moments in the artist’s native Hungary. What did Marx say about the state of the art? Everything in history appears twice, the first time as tragedy, the second as video art.

(The Never Ending) Operetta 42:35 minutes 2008

A neighbourhood symphony and fantasia. Cast in six parts, Kantor’s home movie features his typically hyperbolic collage, his class war sloganeerings, all done up in a hyper kinetic style that winning marries a pop romanticism, video loop reworkings and ironic self parodies. Whether appearing to conduct passing traffic, sharing a blood bath with a friend, or saying hello to his kids in the bathtub, each moment appears as an invitation to awaken and revolt. Gentrification-eviction-extermination-genocide.

7. Istvan Kantor: Spectacle of Noise

Lebensraum-Lifespace: Spectacle of Noise 72 minutes 2004

So what does a Governor General award-winning video artist do in his spare time? If you’re Istvan Kantor, there is no spare time. Instead, the seconds are carved up into small, pointed ice picks that hurl themselves into the eyes in waves of serial repetitions. Everything happens again, every overloaded pictures longs to overcome the senses, and re-locate its revolutionary imperative back into the body. The instrument of control the movie weighs in against is, ironically, the computer and the surveillance camera, the very military/home technologies that make this vid possible. As the medium turns back to look at itself, the mirror mirrored, it produces a dizzying and hysterical mise-en-abyme, filled with sloganeering intertexts, low rent diaries, and romantic warehouse demons.

Can the rhythm of state control also be the rhythm of escape? Watch him try amidst the noise and fury of his isolation. Caught in the infinite mirror of himself, frame after frame. Who isn’t caught in their own patterns of hope and desire? How difficult to embrace these wrong turns, perhaps in the hope of “getting it right” this time, as my shrink advised, in the next iteration of the old story, the familiar disgrace, the reliable failures. And in the meantime, how sweet the jailer sounds.

8. Jenn E. Norton and Kika Thorne: Girl Gang

Nothing touches me, nothing hurts anymore, and everything I ever wanted has been absorbed via broadcast TV. Don’t even call it watching, I don’t watch TV, after all those timeless hours, I have become television. Welcome to the soft spun world of Jenn E. Norton, postmodern avatar of spectacled charm. In her restless screens within screens, high production values mix with digital animations to produce a smooth runway for desire. Pop stars and army pin-up recruiters and glam messiahs all jostle for attention, rising and falling away in a single digital breath. And on the other side, call it pre-digital cable, pre-home computer even, is the work of Kika Thorne, made after hours in a local TV station for a program sisters called She-TV. Her work is experimentalist, grounded in a filmic avant garde, and open to every herstory passing between friends. Smart and sexy.

Chimera 3:30 minutes 2008

Girl glamour as foliage, underwater fauna. A wordless pop morph, this must be where they go when they need to get away from it all. Hey digital, trans-personal, multi-tasker, teen bots, guess what? Heaven is still a lonely place.

Transfer Station 24:24 minutes 2007

This is like watching a year of TV in 20 minutes. Its syrupy surfaces spiraling and blending in order to shape shift one product into another, each personality as replaceable as detergent. It’s a clean, ageless, teenaged forever land out there, every edge rubbed smooth so that nothing will ever hurt you again. Special effects are a way of life. “Welcome to Panoptiscope building a customized reality.” I can hardly wait to see what this will look like on the Visa bill. Teen pop star Cherry Pop (one part Madonna, two parts whoever this week’s flavor-flav might be) summons the dancers for a pre-concert prayer scrum, the artist known as Kunst strikes a bloody pose in interview cutaways, while religious dial ups wait for your call. What are you waiting for?

Whatever by Kika Thorne 21 minutes 1994

Starring Jamaica born poet, Courtnay McFarlane, Whatever takes up the thorny issues of race and identity in an elegant weave of experimental portrait, racial exposition, diary work and ‘coming out’ film. Animated, funny and reflective, McFarlane’s insistence on the political motivations behind private conceits inform the swarm of white woman images which surround him.

Excess 1:20 minutes 2002

A single face encounters itself, the moments of its past and present shrinking and growing and falling away. How can I see my face without all that gravity of attention twisting every corner of it? How can I step across the history of portraits for instance in order to find that long distance runner on the other side of the mirror? And then that thought fades too.

Wee Requiem 6:52 minutes 2010

Beginning with a dead mouse in the middle of her living room floor, the artist spins a tale of concrete language and embodied loss that careens into a vertigo of giants grieving. In this fairytale of solace, this funeral for an unmet friend, she sends her camera and then her post-production gravities into an overlooked world of small wonders.