Mark Interviews

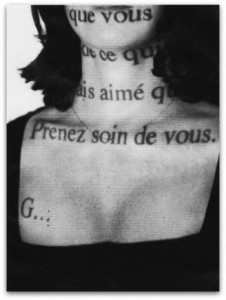

Intelligent Wounds: An interview with Abina Manning (November 2009)

The Fiction I Name as Myself by Jason Whyte (January 2010)

The World is Disappearing: an interview with Adam Nayman (March 2010)

Animal Voices: an interview with Jason Boughton (April, 2010)

The Pleasures of Waiting: Jean Perret and Mike Hoolboom in Jihlava (October 2009)

Intelligent Wounds: An interview with Abina Manning (November 2009)

Abina: In October, 2009, you were in Chicago for Conversations at the Edge and showed your latest feature Mark (70 minutes 2009). Can you tell us a little about it and your process of making it?

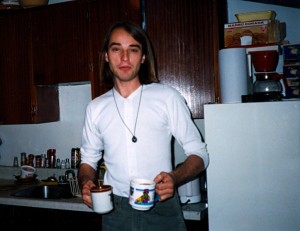

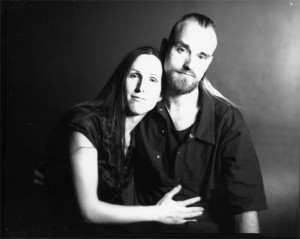

Mike: Mark is a portrait of my friend and former editor Mark Karbusicky. Political vegan, caretaker of feral cats (and his own brood of more than a dozen felines), still punk after all these years. He was a large man who had the presence of someone half his size, able to melt into the smallest shadow of his former self, his smile stretched across everything he couldn’t find words to say. His voice was pitched just above his voice box, a nearly French sounding sing-song which he must have picked up from his partner of ten years, the Quebecois MTF Mirha-Soleil Ross. He was a master of those skills usually not considered skills at all. Listening, waiting, understanding, being present. Everything he ate was politics, and while this occasionally showed itself in demos and office break-ins, it was more often carried in his day to day. His employment, for instance, was housing advocacy for ex-psychiatric patients, and before that caretaking physically disadvantaged folks. He might have unlearned the art of complaining at the punk collective Who’s Emma. Along with the word ‘no’ which he was reluctant to pronounce, no matter how often we sat facing computer silence at the video co-op. He navigated our treacherous communal shareware in between his real jobs which usually meant not sleeping. If you put a needle into his finger he would have bled coffee.

On the last day I saw him alive, he came to my apartment with a shining new edit program, and installed it on my computer, and booted it up not once but twice, and even guided me to digitize clips and lay them on a timeline. It was a typical Mark performance: thorough, meticulous, and free from any worried fussiness. He had been urging me for years to work at home, even though that would probably mean leaving Mark as an editor. I didn’t realize then that this was his way of saying good-bye. He was dead less than two months later. His feet hovering an inch or so off the steps that separated upstairs from down. There was no room for error in his death, and it was no cry for help. Like everything else in his life, it had been researched, deliberated, executed. He didn’t leave a note.

For me, for many of his friends and family, his death came as a sudden and terrifying shock. He was just thirty five years old, healthy and beautiful and filled with a geek know-how that faced down every new glitch with a fascinated and easygoing determination. Perhaps not so easygoing in the end. The movie is a way to say hello and good-bye, to introduce him to strangers, to run my fingers over his pictures. Along the way I visited with his old childhood friend Andrew Vollmar who lived, up until last year, in the very same apartment they both grew up in. And Lauren Corman, who has just become Canada’s first animal studies prof. Kristyn Dunnion aka Miss Kitty Galore is a queercore punk novelist and member of all-girl metal band Heavy Filth. Lorena Elke is a political vegan, trained in the Celtic Faery Tradition of witchcraft and an animal rights activist. Mark’s life partner, Mirha-Soleil Ross, is a media/performance artist and activist, a slightly larger-than-life speed talker and working class mega donna. Each makes their own approach to Mark, and they are knit together to create a mosaic of intimate distances.

Abina: I hear that you will be making a new edit of the film. Did you take anything from the Chicago screening that you will utilize in the editing process?

Mike: Digital media resists traditional closure, which might mean: no more monuments or heroes. Though I have to admit a weakness for recutting. Behind the impulse to make every movie there is some infantile wish to go back and fix the past. Sharpen conversations, fine tune punch lines and interludes. Next week, for instance, I will begin recutting Tom (75 minutes 2002), which will likely shrink by fifteen or twenty minutes. There are no plans to air out this new version, it will simply make me sleep better.

What my work presents is a temporarily optimal arrangement. Much of it is available as free online downloads, and in place of a copyright warning there is a note urging viewers to steal as much of the movie as they please, and reversion according to their own necessities. Sofar as the Chicago screening went, the fact that Mark worked as my editor was unclear until the very end of the movie, an ambiguity that was quickly corrected by changing a single line. Further sound level and colour adjustments have occurred, and additional picture layerings in soft areas. The work continues.

Abina: One review of the screening says, “The film traces the life of a man you end up knowing less about in the end than you did to begin with. It is an odd portrait in that it seems to capture more the periphery of his life than actually attempting to memorialize the man himself.” (Lauren Vallone, http://badatsports.com/2009/mike-hoolbooms-mark-the-gene-siskel-film-center/). Would you agree with this analysis? And if you do, was this a conscious decision on your part to avoid a more typical filmic portrait?

Mike: How curious that this review grants such weight to the moments before and after the movie. A chance remark made by way of introduction, or in response to a stranger’s query, becomes part of the movie, as foreword and footnote, a frame as absorbing as its picture.

Because Mark was not more famous than his neighborhood, it seems unlikely that the reviewer, or anyone else in the audience, would know anything about him. So it’s a stretch to write that by the movie’s end these strangers know less than nothing. There are childhood friends and intimate testimonials, his mother, his stage appearances, dinner at home, an afternoon with his niece and nephew. But at the same time, Mark was rarely at the centre of his own life, he wasn’t the one taking the bows or chasing the limelight. Instead, his preferred place was always behind the scenes, pulling focus, putting up the scenery. Forever busy. His endless rounds of feral cat feedings, or animal rights organizings or daily housing advocacies were all done quietly, and nearly invisibly. He had the lightest of all possible touches, as if he were never quite in the room, already dematerializing. How do you make a picture of the background? How do you keep the movie turning about this emptied centre without filling it with false promises, or the worshipful hagiography that follows nearly anyone’s death?

For the past ten years I have been working on questions of the portrait. It began with Tom (75 minutes 2002) which married two incongruous genres: the biography and the found footage movie. It proceeded with a reworking of the home movie in Jack (15 minutes 2003), which became the central figure of the next feature Imitations of Life (75 minutes 2003). The following year Public Lighting (70 minutes 2004) examined the “seven types of personality,” offering portraits of Madonna and Philip Glass, amongst other luminaries. And then Fascination (70 minutes 2006) replayed iconic video artist Colin Campbell as a cold warrior. Mark was my editor in most of these travels, so it seemed only too likely that the first movie I would make with the software he left behind would be about him.

Abina: You are an artist who is incredibly interested in, and supportive of, other artist’s work. You have produced two books of interviews, written scores of reviews, published monographs, essays, along with your work as a curator. What drives this interest?

Mike: In the past two years I have released, co-authored or co-edited eleven books, many of them available for free download on my website. Most of this work is about individual media artists. It is a field which continues to be underrepresented in print, for reasons which escape me. It is possible to press a small CD release and count on half a dozen well considered reviews on the web. And there are magazines like The Wire which doesn’t think it strange to mix-master prog dinosaurs King Crimson, drone symphonist Ben Frost and New York’s Sensational-Freak Styler. But the words swirling around artist’s film and video are mostly in a state of live quarantine at the screening itself.

Jean Perret, genius director of the Swiss doc fest in Nyon, said that there are two kinds of filmmakers: the ones who search and the ones who find. The ones who already know what they are looking for, and the ones who set off to find out. I share an anthropologist’s interest in my fellow searchers, as we move together in the dark, each in our own way. Because we are busy trying to open to the next necessary and impossible emotion, when I speak to them they are packed to bursting with deviant myths, border crossing insights, and intelligent wounds. Is it too awful to admit I find them irresistible?

Abina: What are your current influences? What are you reading and watching?

Mike: I’ve just finished reading Frida Kahlo’s diaries in preparation for a new movie, and J.M.Coetzee’s devastating The Lives of Animals. I’m looking forward to Jon Davies’ Trash (A Queer Film Classic), and Jayce Salloum: History of the Present, a mid-career monograph about this genius multi-media artist. In between episodes of Grey’s Anatomy anything by Steve Reinke is essential viewing, including his latest punk rock collaboration Disambiguation), and the sterling chops of Frédéric Moffet in Jean Genet in Chicago. Amy Goodman and Democracy Now, whatever Naomi Klein is writing about and Dani Leventhal’s post-diary video: absolutely. But what influences me most of all is hanging around friends and their kids. I have never seen people work so hard, and with such selfless patience. I have a score of new friends, maestros every one. All of my most important teachers are not yet ten years old.

This interview was conducted via email during November 2009.

Abina Manning is the director of the Video Data Bank. Prior to coming to the VDB in 1999, she worked with a number of arts organizations in the U.K., including the LUX Center, the London Film Maker’s Co-op, London Electronic Arts, and Cinema of Women. She was Director of the inaugural Pandæmonium Festival of Moving Images, a major European exhibition presented by the Institute for Contemporary Arts in London that showcased film, video, gallery commissions, and multi-media works.

Note: Many of Mike Hoolboom’s works are available through the Video Data Bank, and can be viewed at our on-site screening room in Chicago.

The Fiction I Name as Myself by Jason Whyte (January 2010)

Jason Whyte: Please describe your movie in a paragraph to entice people to come see the movie at this year’s Victoria Film Festival.

Mike: A sidelong biography of my friend and long time editor Mark Karbusicky. Animal rights activist, political vegan, punk maestro, the life-partner of Mirha-Soleil Ross, a transsexual force of nature.

Jason: Is this your first film at the Victoria Film Festival? Tell me about your festival experience, and if you plan to attend Victoria for the film’s screenings.

Mike: The festival has been very kind to me in the past, while I have never attended its luxurious outpourings, it has been a home for my work for many years.

Jason: Tell me a little bit about yourself and your background, and what led you to the industry.

Mike: I am industrious, but not part of any industry. There are no commissioning editors or producing agents requiring attention. Instead, my work comes from a personal place, it touches the people around me, and it takes shape as our encounters develop. Why is every hockey game lensed the same way, when each game is so different? Would you enjoy having the same conversation with each of your friends? The pictures I am interested in come from this necessary place of intimacy, which involves risk on both sides of the camera. While I try to remain, as Leonard Cohen put it more than once, on the front line of my own life, I am not an embedded reporter. There is no objectivity, and no objects. Instead: subjects, waiting for the right light, the right distance, in order to arrive in all their necessary loneliness.

Jason: How did this whole project come together?

Mike: The impossible happened, the thing that was never supposed to occur, the unimaginable event. My friend died. How could he die? That’s how the movie started. All of the important things in my life have happened by accident. I think as a filmmaker, learning to listen to your accidents is the most important quality. I didn’t begin making a movie right away, I came to his house so I could feed his cats and walk his dog. Every moment of that architecture was funerary, and I wanted to make a record of it. Every bit of carpet, every photograph, every unwashed dish. That’s how it started. I wanted to build a small archive to shore up the ruin, to ease the pain of losing him.

Jason: Please tell me about the technical side of the film; your relation to the film’s cinematographer, what the film was shot on and why it was decided to be photographed this way.

Mike: The movie was made up in the dark, conjured a moment at a time. At first it was moments of Mark’s apartment which fascinated, but then there were encounters which could no longer be put off. The maximum impact moment of our lives. How could the camera arrive at this place, with its mute digital stare, its ability to see almost nothing, no matter how long it was busy recording? How very busy many of us are producing what we imagine to be pictures, but which turn out, in the edit room, to be no pictures at all, but only placeholders. If only we had time to look, or look again. What I tried to learn, by steeping myself in the remnants of what Mark had left behind, was how to find the necessary distance between those who were willing to step forward and testify and their digital witness. What would they say? How would they appear? I had no way of knowing, and a lifetime of watching scratches accumulate on emulsion seemed inadequate preparation. I was blessed with the fortitude and rare articulation of some of his familiars, who were ready to hold forth, at length, even while language proved inadequate, our gestures already too small and faraway to measure up against the gravity of what had happened. And yet. They were determined to leave a trace, and I tried to be there when they did, and gather up the puddles, and let them drip into the lens. Slowly, as the months crawled past, these began to accumulate. The way she sat on the couch, looking glamorous even through her tears. The way another presented before the radio station microphone, decomposing. The way her candles lit up the most distant corners of her face. It was from these faraway places (the furthest flung geography of her own face) that she began to reel him back in, one word at a time, one memory following another. For instance, she tells me about the rescue. (But who will rescue the rescuer?) Mark had come to help Lorena bring in a posse of wild cats on night. What were they using to wrap up their charge, to bring them into safety? It was raining and one had chased itself away. Mark was over the brush in a flash, and returned several minutes later with the small scratching kitten held in one hand. He was interested only in the strays, the ones left behind, the discarded and unwanted. Perhaps because he himself felt… no, I don’t even need to say it.

Jason: Out of the entire production, what was the most difficult aspect of making this film? Also, what was the most pleasurable moment?

Mike: The most difficult part of making the movie was its beginning. It was never supposed to happen. How to stay inside that place? How to live inside the impossible?

Jason: Who would you say are your biggest inspirations in the film world (directors, actors, cinematographers, etc)? Did you have any direct inspirations from filmmakers for this film in particular?

Mike: I marvel at the way Chantal Akerman shoots her movies. I imagine her arriving at the scene, at the border between Mexico and the United States, the line-up for bread in Moscow, the blinking lights of a hotel corridor. And there she waits. She might wait for a long time, at least long enough to imagine living in a place just like this. She waits for the light to come to her, for the scene to be birthed inside her again. Setting up the camera on its three-legged foundation is a way of staking out a position, it is finally a question of a moral authority. So when the film at last begins to roll through her machine of seeing she is prepared to let it run for a long time, and in the movie’s projection we are granted the luxury of her waiting, of the time she creates around her frames, her subjects, her shots. She shows us how to make this time in our own lives, and with our own subjects. It is exactly this time in which the small gestures that make love possible recur again and again. Noticed at long last.

Jason: How has the film been received at other festivals or screenings? Do you have any interesting stories about how this film has screened before? What do you think you will expect at the film’s screenings at Victoria?

Mike: What could I expect? Fan mail? Flowers? Offers of undreamt pleasures? My arms are as open as my expectations.

I took the movie on a test drive in the fall: Montreal, Milwaukee, Chicago, Syracuse. Because of its personal nature, many approached me afterwards and shared their stories. I made further adjustments, and now it is having its second public life: along with the screening in Victoria, it will have its international premiere in Rotterdam next week, then tour Mexico in February/March, Switzerland in April, and Toronto in May.

Jason: If you weren’t making movies, what other line or work do you feel you’d be in?

Mike: I think I would make a very good rich person. I would know which hands to fill, while encouraging unions of every kind. At a certain moment I would leave them the keys: here, take it, it’s all yours. On the other hand, the job I am haunted by is the one that Joey (or is it Pete?) works in Goin’ Down the Road. He sets up bowling pins – by hand. I saw this movie when I was very young and thought: well, I guess that’s how adults spend their time.

Jason: How important do you think the critical/media response is to film these days, be it a large production, independent film or festival title?

Mike: In the too-muchness of this moment, with information deluge arriving on personal tickers day and night (how long before advertisers find a way to re-brand our dreams?), how else can a movie – most particularly those with modest means – find an audience? If I were a novelist, my books would not be better because I spent a million dollars writing them. Ditto a painter, sculptor, dancer… But in the movies, bigger is presumed better. Lack of money signals a lack of imagination. Besides, the gravity of making urges every maker to repeat. Please repeat after me. Making movies is like figuring out how to dress in high school, it is generally not done to communicate, or even to express a style, a point of view, an inclination. Instead, pictures are made to get along. The theme song of today’s movies is: please let me belong.

There has been a great levelling of film writing, which increasingly approaches the ideal of shopping. I want it, I don’t want it. Thumbs up or down. How could writing create light in order to see? From Christopher Sorrentino’s Trance: “There was a time when Alice thought it was possible that a poem or a song could save every faltering affair in the universe; there was a time when Alice thought she would use it, as she might an incantation, on a night when the TV finally ran out of things to say.”

Jason: If your film could play in any movie theatre in the world, which one would you choose?

Mike: The one it is playing in now.

Jason: If you could offer a nickel’s worth of free advice to someone who wanted to make movies, what nuggets of wisdom would you offer?

Mike: I am with Werner Herzog: don’t go to film school, steal whatever you need, and take a long trip by foot. Go for a ten day silent vipassana retreat and change the world. Then get a camera and a laptop and change the world again.

Jason: What do you love the most about film and the filmmaking business?

Mike: I love that film is not a business at all. I love the way that one impossible moment, with that beautiful light, can reach across the infinitude of a cut and find another moment, so very distant, even unimaginable, and find new life inside that juxtaposition. In the new movie I am working on (working title: Lacan’s Palestine), philosopher genius Mike Cartmell dishes Harold Bloom’s theories on the anxiety of influence, and how it is necessary for the younger artist to re-write the strong work of their elder. What follows are moments from the Gaza checkpoints in Palestine. Could this budding nation rewrite the oppression that threatens to drown it at every turn?

Jason: A question that is easy for some but not for others and always gets a different response: what is your favourite film of all time?

Mike: My biologist friends assures me that constant cell replacement ensures that every seven years we are completely different people. This means that tastes change, and that the fiction I name as myself is in constant flux. My favourite movie used to be Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinema, Steve Reinke’s The Hundred Videos, Yvonne Rainer’s Journeys from Berlin/1971, Trinh T. Minh-ha’s Reassemblage. Today my favourite film is the view from my window.

The World is Disappearing: an interview with Adam Nayman (March 2010)

Adam: I’m sure you’ve spoken about your relationship to your subject as the film has made the festival rounds, but if you could take me through your initial impulse to make it, that would be great. Given Mark’s apparent tendency towards self-effacement (his ecstatic Blondie performances notwithstanding!) was there any fear that “bringing the background into the foreground” (as I believe you put it in your voiceover) would run counter to his wishes?

Mike: When I was young I thought we would all walk on the moon, that Martin Luther King would be the first black President, that pollution would be cured by science, not caused by it. And that an atomic bomb would wipe out most of the planet. These were not dreams, but the writing on the wall. I don’t know what Mark read on that wall, but this film was certainly not part of the outlook. How many times have I caught myself in conversation with one of his familiars when we have to stop and say wait. We’ve been talking about Mark for how long now? If he could have imagined even a smidgen of this attention, it would have made his death impossible. How small do you have to feel before it’s not worth going on any longer? Until you can be toppled over by a stop sign turning colours? Or a casual remark shared between strangers? What special quality is it that manages to absorb every bad feeling – trapping them and making them grow large and luxurious – while all the good feelings pass away unnoticed and ignored?

Mark and I made movies for many years together, sitting in the dark of our lives, watching pictures scroll past. There were many difficult decisions to be made during this one, decisions which another filmmaker, a little further removed from events, would have judged simply in terms of the movie and its requirements. Instead, I needed to follow the ghost of my friend, and ask again: what would Mark want? What would Mark do now?

I attached dangerous fantasies to this movie, though these are only beginning to be admitted now, in the wake of their too obvious failure. Mark’s death, like many catastrophes, seems an endlessly renewable gift, and occasioned many ugly scenes and confrontations. Death threats, hospitalizations, police… It was my hope that this movie might join “us” in a celebratory communion, and at the very least allow our friend to walk on water again. These hopes also seem like part of another time, someone else’s script. The someone else who might have begun this project, for instance, which I couldn’t imagine doing now, no matter how often the unseen visitor keeps knocking on the door. Why make this movie? To let him say what he couldn’t. To let us all say what we weren’t able to say when it mattered, when he was still here. To allow us to speak when it is too late, after the doors have closed, and everyone has gone home, and it’s all been forgotten. To hold up this small movie, this small life, and ask that it too might be counted.

Beginnings will forever be a male preoccupation, perhaps because our relation to paternity is so abstract. While the Hollywood version of my life (which I have been busy casting since the age of six or seven) is filled with decisive moments, I can’t honestly say when I decided to become friends with my friends, when I started a movie, where these words come from. I would like to imagine that my executive function is fully operative, but have to admit that the accidental is finally more persuasive. For the documentary filmmaker, chance encounters are a way of gauging whether you’re on the right track. Did this movie really begin when we met, and will it finally end when I’m dead, or only after that, when Mark and I can resume our montage of the afterworld?

Adam: I loved the motif of invisibility (was that a clip from Verhoeven’s Hollow Man early on?), and the running through line of mainstream genre films (Cat People, Twister, Frankenstein, others I’m sure I missed). Does the appropriation of those film texts speak to Mark’s interest in media/collage or your own, or are the two linked given that he worked as your editor?

Mike: The movies that Mark and I worked on were all biographies, which I would like to name as coincidence, despite mounting evidence to the contrary. This biographical urge was married, very early on, with an interest in “found footage,” pictures that could be stolen, hijacked, lifted, boosted, shot off screens, downloaded, transferred. Digital media puts image theft at the very heart of its making. Movies are no longer finished, only offered as up in versions, parts of which will be cannibalized for other purposes, like Youtube clips, or website jawdrops, but also other productions with their own needs and hopes. Mark and I married found footage with the question of digital biography until the perimeter of our subjects exploded with quotations, clips, sound bites and borrowed licks. The way we dress, the hopes we have for our bodies, the way we experience work, home, desire, time – doesn’t all this begin as pictures made by others? Call it the death of the author. There was a moment when it seemed it would no longer be necessary to make another picture, cinema could instead be dedicated to recycling the too much of what had already been produced.

This movie blends familiar and unfamiliar pictures in hopefully useful ways. Frankenstein is an obvious enough metaphor for any biographical undertaking – stitching together parts of bodies, experiences and sensations in the computer/lab/editing station, in order to create “new life.” My movie, my monster. Cat People (1942) takes a turn as Lorena Elke speaks of her political veganism and fathoms deep commitment to animals. It shows a woman who moves in sympathy with the animals who prowl around her, as the great leopard paces the cage, she paces outside it, and when her sexual advances are frustrated, she rakes her nails down a couch cushion like a cat. The Invisible Man (both in its serialized form and remakes) became a recurring pulse in the movie, metaphor perhaps for the absent centre around which the movie turns, the Mark that shirked the duty of presentation, preferring instead to work behind the scenes.

Adam: It might be a sensitive question, but do you think that editing this film in Mark’s absence has changed or developed you as a filmmaker? Was it hard to take this material into the editing room in light of your subject?

Mike: The Rotterdam Festival wrote that this was the first movie I had edited myself. What a wonderful fiction. I had worked for many years as a filmmaker, and only accidentally took up video (the other side, the dreaded enemy), where I tried to reinvent my practice. This meant, amongst other things, leaving all of its difficult technical matters to smart people like Mark. I needed to create a new and necessary distance between the seductive abyss of these pictures and myself, so it was always Mark’s capable hands on the machine. Together, we tried to create new stories out of these borrowed fragments, harvesting pictures to make new lives possible.

Was it hard to take this material into the editing room? It was all I ever wanted to do, and it was all I ever hoped to stay away from, blessing and curse all at once. There were days I could hardly get out of bed knowing that I would have to see all of his sad friends again, caught in the stricken aftermath moments of his death. How to find a way to deliver all that pain and difficulty without making a painful and difficult movie?

Mark had urged me for many years to work by myself, at home, perhaps in part because there is an understanding, a knowledge, that comes up out of the body, in relation to the pictures which are always busy gathering around us. As someone used to making films, the feeling of materials had been a central and motivating part of the process. Editing film means cutting physical pieces of matter and taping them together. Hanging strips on walls or bins, marking up collections of strips, winding them on cores, all that. In video this is done digitally, virtually, inside the machine, so the arguments for tactile engagements seemed remote. And yet, as I ran these intimate pictures through my digital fingers, I could feel them changing, and my relationship deepened, exactly as Mark said it would.

Adam: How much of that footage did you film yourself over the years? You must have received filmed material from a variety of sources (friends, colleagues, etc). Was any of it especially difficult to find?

Mike: I admitted each new encounter into the movie reluctantly, and with great hesitation. My preference would have been to mail a camera to each of his friends, ask them to say whatever they could, and then return to sender. Instead, we watched him die between us at each meeting, and this is what I recorded. Mirha-Soleil Ross, Kristyn Dunnion, Lauren Corman, Lorena Elke and Andrew Vollmar all stepped up and I can’t thank them enough for their courage and grace.

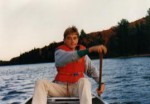

I was very fortunate in having access to an unusual archive kept by Mark and his life partner Mirha-Soleil Ross. They had organized two trans art/performance fests which were extensively documented, along with talks, demonstrations, and public acclamations (Mirha-Soleil was Grand Marshall of the Toronto Queer Pride Parade in 2001). Secreted between these very public declarations were home movie moments, a cross-country trek to visit Mark’s parents, a video letter home, Mark eating noodles. I was very fortunate in having access to this. To watch him jump up on a rock, or paddle a canoe; all that was thrilling beyond measure.

Mark and I grew up in the west end of Burlington, in an area known as Aldershot. Home of the newly disaffected. I returned often while making the movie to hang out and shoot with my nephew, who became Mark’s younger incarnation, and to visit the parks and streets and neighborhoods where we both learned to look without seeing. Mark’s uncle, who also took his own life, is buried there in a small graveyard, not far from Mark’s old grade school, and the high school we both attended. Returning to that bell ringing institution with my skateboarding nephew skimming through the hallways was a ghostly enterprise. There is a way to raise the camera so that it will only have an eye for phantoms and disappearance. And there is a way to look at footage already gathered, whether it appears in well known blockbusters or obscure delicacies, that can also yield traces of these forgotten phantoms. The world is continually disappearing, and often offers up a spasm of presentation, a final glimmer, before departing. That’s what I’ve been training my attention towards, and Mark along with me, for as long as he was able. To catch the wave good-bye.

Animal Voices: an interview with Jason Boughton (April, 2010)

Jason: I can’t wait to see the movie. I have no picture of it in my mind at all, however much you have hinted at its hybrid production, and the harrowing position you were sometimes in, whether alone or shared with other participants. I’m quite terrified to see it, but look forward to it, with fear. Can’t let the Jesus freaks have all the fun. Bring it, Motherfucker. By “bring,” I mean, “reflect deeply upon, in a manner approaching ecstasy.” By “it” I mean “the limit case of human experience, that before which the subject stands wholly alone.” By “motherfucker” I mean “motherfucker.”

Mike: You mentioned in last night’s post-Skype phone resorting that the very best way for me to proceed would be to play outside the comfort zone. Don’t rely on those old chops. And I have been feeling that too. Call it the necessity of failure. Let me try to write that poetry in another language, pitch left handed, have the most delicate and intimate conversations only when I haven’t slept for a week.

Here is my fantasy: there are only two kinds of artists in the world. The first artist takes everything they’ve ever done in their life: every conversation, every humiliating moment in bed, every punishing childhood memory, every high and low that might have run through their veins, and they pick up a paintbrush and make a single stroke across the canvas. There. There it is. All of that living, and feeling and wanting and surrender are all up in that line. And not only that, but the line belongs to them. You can watch it from a city block away and know straight up, oh yes, that line can only belong to one person.

And the other artist? Well, the other one is also confronted with conversations, the touches of familiars who grow stranger as they get closer, with the usual sing-song of hope and reconciliation, only when they haul out their canvas they don’t make a single line. No, every time something happens they scribble a little something down, they paste some comic book panels in, maybe a few newspaper headlines, a shopping list, random articles of clothing, and they seal it with a kiss. This motley collection belongs to the collage artist, the junkyard flâneur, the postmodern undecided, and yes, I belong to this tribe. Though of course I long, and not so secretly, to be the former artist. The one who is rigorous, and always decided, and certain. The minimalist summarizer.

What I haven’t figured out is how this artist, the one who always knows, the one for whom “first thought best thought” is forever operational, the one who gets up in the morning and has to haul out their notation book so they can quickly scribble out that symphony before it gets lost in the notes of an ordinary day, how does this artist grow? How do artists get better?

Of course for some it is impossible. The very first things they ever did are so fine, they will never again make anything as good. No doubt their public, their galleries or dealers, perhaps even their friends, or ex-friends, will help remind them of this. These artists are made to compete with themselves, and so they appear as ghosts, haunted by some younger, more perfect version of themselves. As if they were some faded rock act on a reunion tour, forced to grind out almost hits of years past. Call it nostalgia for a generation without memory.

My friend Phil says that any artist has only a couple of possibly great things in them, perhaps even a great period, while the rest of the work is place holders. Perhaps getting better as an artist means trying to work on your place holders. Tuning up, sharpening your smarts in the in-between moments.

I have long ago given up on hopes of great or masterful, these seem ideas that more properly belong to centuries past. How happy I am to be working in a digital domain that will shortly be entirely unreadable – just ask anyone who has tried to rescue their hard drives from a few years ago. Yes, I am confident that virtually everything made today will sink into digital oblivion, never to return, and this brings me more comfort than perhaps it should. But in the meantime, before the great forgetting begins in earnest, I would like to get better. Call it a tic, a habit I can’t shake. But I feel, now more than ever, that I am surrounded by low resolution pictures. Low resolution intentions. Low resolution montage. I have contributed more than my share to this sub-optimal movie pile. Along with the nightly news cast, the commissioned-by-television documentary, the Youtube clippers.

Because I still occasionally throw shadows into what some like to name, sans tongue in cheek, as the art world, I am haunted by the idea that there’s this one thing that I should be doing, over and over, which will be the evidence, the symptom, of my “trait,” the thing which is my thing, the gesture I can contribute and chip into the pot. But the pictures which accumulate on my desk top are not my own, instead, they arrive with labels like “earthquake victims” or “Afghanistan” or “war”, but manage only to occlude any possibility of looking at all. Most seem as if they have been made by tourists in a great rush, and edited by a six year old with hyperactive presentation skills, to ensure that if any moment of real looking might occur, it would be cut short enough to ensure that no one will notice it. Given the pressing need of pictures which show instead of conceal, I am finding that my avant-garde boot camp is not proving sufficient, even for the local circumstances I am continuing to drown in. The movie about my friend Mark, for instance, is a place I don’t belong. It, the project, has to rub its digital face into the grime of his real life, his grief-struck parents, his shocked friends. This is not my home. I grew up inside the avant family, filled with formalist dreams of emulsion. In our living room, the signifier was everything. I struggled for two years with Peter Gidal’s Theory of Structural Materialist Film (1976) where he argued that the representation of people, any people, doing anything at all, was politically retrograde. I still meet fringe makers who are loathe to turn their cameras in the direction of fellow humanoids because they feel it is unethical. How to take this deep backgrounding and turn it towards the aftermath of a suicide? What I would prefer instead is never to leave my apartment, to work only with “found” footage that I might knit together with documentary fictions and music that sounds like overworked air conditioning units.

Jason: Funny, I’ve never experienced your work as mute formalism, much less a strident materialist encounter with the physical apparatus, or anything other than an opening up to the Real. Was Mark a sort of analysis where speech “realizes in the Symbolic” the empty spaces of trauma? Are the syntactical maneuvers of filmmaking your Symbolic vocabulary? Or is it at an additional remove? Is that moment which feels the rightest also the most formalized representation of a language which formalizes speech, but not actually THE language? Or is there a difference? How is that different in this case, this film, this arrangement of sensual objects, than in any other?

Mike: You’ve never seen my celebration of film grain in Song for Mixed Choir (8 minutes 1980)? Or the movie that offers up a series of intertitles asking the audience to “Please Stand” or “Make a sound only you can hear”? Materialist excursions, yes, every one. I’m sure you remember the movie that Ernie Gehr made by cracking open the lid of his now light-leaking Bolex that he almost covered with cheesecloth, allowing the blindsided film to be struck from behind, creating the barest of grain patterns, but no image. Yes that’s it, only grain. White boy dared to call this movie: History. And after there was Mike Snow’s reaction shot: At last! The first film! That was my home too.

Mark (70 minutes 2009) was finished two days ago. So notes on its hope or making are at best speculative. Perhaps it would be easier to speak of it in the future tense. I don’t know enough about the Symbolic, or the empty spaces of trauma to be able to answer your queries. Though I cried more than once as his friends, who I met for the first time in the weeks after his sudden death, delivered their testimony to my camera-heart prosthesis. And because I will never be one of those perfect filmmakers who are able to settle their three-legged vision machines at the optimal place, and let it run for the right amount of time, at the correct distance from their subject, and whose editing consists of the marriage of these perfectly present moments of witness, I need instead to load my pictures into the computer and pore over them again and again. Yes, I need to meet Mark’s friends over and over at this moment of maximal impact. In the place which can’t be borne, speaking words which can’t be spoken, feeling only that which cannot be named.

It was my task to try to find a way to deliver these faces and encounters to perfect strangers. To try to impart to the movie something of the lightness and grace that Mark had as he floated into the room, or that airy singsong way he had of speaking. I tried to do this via editing, perhaps an obvious enough choice given that Mark worked as my editor for so many years. The rhythm of recollection may also be, as you describe it, “the formalized representation of a language.” It is also a way to testify, to bear witness. Like the way someone moves their hands while they talk. Those hands are an accompaniment to language, but also, in their dance, something more. They point to something else. The hope of ghosts perhaps.

Jason: A related question: what’s the goal? Not in this film, but in general? To produce pleasure? Obviously by pleasure I mean: affect, transformation, sensual and psychical vibration – in whatever flavor or register. Or instead, are you trying to produce meaning? Are they sometimes or ever homologous?

I’m going to stop myself here. I’ll send this anyway, even though I think this is entirely the wrong line of approach. Totally wrong, in fact. I’m going to watch it again, and read something in Kaja Silverman, and then get back to you later…

Mike: What’s the goal? You mean: what’s the point? Why make anything at all in a world already too full of it? It’s true, I often think of the moment when it would be possible to see every movie ever made. To circumnavigate the small world of movies. Surely there were so many centuries when a local library or church would contain the sum of all books or art available. My library, my world. But now digital media has allowed a promiscuous access, as you know better than anyone, inveterate downloader that you are. Is the aim of production simply to add to that relentless stockpiling of reproductions which various micro-niches are busily downloading and occasionally experiencing, perhaps as background to party chatter, or motion picture wallpaper murals while the news is playing? How lovely it would be to imagine multiple uses outside the usual run of avant safe houses and sanctified art templates. The immediate goal for Mark’s movie, though, was something much more modest. To be able to share something of my experience of Mark with those who didn’t know him. Call it translation. Or ventriloquism. Will it be enough?

I have just finished reading Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz. Its Italian title is Se questo é un uomo, and its earliest English translation offered the book up under a more faithful translation: If This Is A Man. In it, he speaks of a recurring dream he had in the Lager, dreams which began shortly after arriving.

“This is my sister here, with some unidentifiable friend and many other people. They are all listening to me and it is this very story that I am telling: the whistle of three notes, the hard bed, my neighbour whom I would like to move, but whom I am afraid to wake as he is stronger than me. I also speak diffusely of our hunger and of the lice-control, and of the Kapo who hit me on the nose and then sent me to wash myself as I was bleeding. It is an intense pleasure, physical, inexpressible, to be at home, among friendly people and to have so many things to recount: but I cannot help noticing that my listeners do not follow me. In fact, they are completely indifferent: they speak confusedly of other things among themselves, as if I was not there. My sister looks at me, gets up and goes away without a word.

A desolating grief is now born in me, like certain barely remembered pains of one’s early infancy. It is pain in its pure state, not tempered by a sense of reality and by the intrusion of extraneous circumstances, a pain like that which makes children cry; and it is better for me to swim once again up to the surface, but this time I deliberately open my eyes to have a guarantee in front of me of being effectively awake.

My dream stands in front of me, still warm, and although awake I am still full of its anguish: and then I remember that it is not a haphazard dream, but that I have dreamed it not once but many times since I arrived here, with hardly any variations of environment or details. I am now quite awake and I remember that I have recounted it to Alberto and that he confided to me, to my amazement, that it is also his dream and the dream of many others, perhaps of everyone. Why does it happen? Why is the pain of every day translated so constantly into our dreams, in the ever-repeated scene of the unlistened-to story?”

Perhaps every movie shares this ambition: to reveal the trace of someone who has been here, who looked like this, who left this mark behind. Every movie is a funerary monument, a crypt. But every movie might be haunted by the shared dream of the Lager: that the story it is trying to tell will not be understood. That the act of translation, the gesture of transforming what happened from a lived experience into media transmission, will render the story mute or unintelligible. Or perhaps the listeners are simply too distracted to notice, no matter what efforts of recollection are made on their behalf. The dead are busy waving on the other side, the graveyards are full, every day, every minute, there is another funeral. Who has time to remember? To bear witness?

Pleasure not enjoyment

But wait. You are asking whether the movie has arrived out of a need to inform, to tell, to bear witness, or instead, to produce pleasure. Perhaps it seems disingenuous to say that I hoped that announcing my friend’s death to strangers would bring pleasure. Then did I imagine it would bring me pleasure? My personal philosopher muse Mike Cartmell would name this enjoyment (jouissance), I suspect. Enjoyment, not pleasure.

“Enjoyment is difficult and dangerous and not necessarily pleasant. There’s a lot of enjoyment in torturing yourself with your mean-spirited self judgments. There must be, otherwise we wouldn’t keep doing it. Enjoyment doesn’t always produce effects that everyone would opt for. That’s pretty clear from the way in which people take up the sexual relation, so called, for instance. Or repeating steps that cause anguish or pain or grief. Why do you keep doing it? Must be something in it. Some jouissance. Some enjoyment. The exactions that you require for enjoyment. It’s strict and rigorous, rather than mellow, pleasurable and relaxing. If the drive is ultimately the death drive, then what you’re seeking is a complete cessation of everything. The drive seeks its ultimate expression in annihilation. Maybe that’s the ultimate expression of enjoyment, though it would be unconscious. Why do people constantly rearticulate the same wayward path that brings them nothing but pain? They do it all the time.”

Perhaps this movie, this way of life, began somewhere after Public Lighting (2004), when I was waiting for a mission. I knew it would come by chance, probably by the telephone. When you don’t leave your apartment much, chance encounters happen digitally, or at least at one remove, via tech prosthetics. It was Lisa Steele who finally called, asking if I would contribute a short work for an evening of new videos inspired by the work of Colin Campbell, cross-dressing Canadian video avatar. Three years later I had dragged myself across the doorsteps of some of his many friends and once loves, and waited as they struggled to remember, and cried, and drank themselves back to good cheer. I had met Colin exactly twice, for a total of roughly three clocked minutes. Do extras have stand-ins? I said hi at a crowded dinner table, strictly in passerby mode. And then there was a second chance when he approached at a Vtape opening. It was hard to believe we intersected so seldomly, though in our salad days the reigning art popes oversaw the catechism of film and video, so perhaps it was no accident we were never in the same room. The point is only this: I hardly knew him, and then I am party to the annual forget-me-not wakes on Halloween, when even the masks have tears.

And then Mark died, and I rushed to that graveside too, staggered round the parking lot with his disbelieving parents, looked into all those hard, worn faces at the memorial and thought: yes, this is my home. He was my editor, the hired help, a bottom’s bottom that I tried not to run up over in my rush to feed super ego interdictions. That settled after the first enfeebled months as we found a way through his need to be hurt again and again. We decelerated, and spent face time in the hopeless video co-op that someone else called home, pulling out the wires and cords and hard drives, peeking at our projects through the signal failures. I’m trying to bring this round to answering your question again Jason: what is the goal? Well, surely the goal wasn’t to tell this storyless story, of a man I met so often and hardly knew. The one who could speak so beautifully about nothing at all and stay silent on absolutely everything that mattered. Like, for instance, the fact that he was so depressed he wanted to kill himself. For instance. The things we didn’t say to each other. Perhaps that’s what the movie is about. The offscreen space, the sidelines, the time it takes to get to the place you really want to be that you wind up spending your entire life in.

Or perhaps, in the traditional parlance of the avant movie scene, it is a demonstration of the maker’s unique “seeing.” Because one fortunate or not aptitude I seem to have developed is to be able to look into a face and watch it grow old and die, right in front of me. I am not projecting or imagining when I see this, I am not in the world of fiction, only documentary. It is the place I am looking out from, every day is fall or winter, everything is dying, falling from the branch, withering, fading, disappearing. Every face I loved is gone. And in Mark’s movie, with its eruptive and restless shifts, there is, or so I imagine, a sense that the leaves are turning, the face in the window is turning, the hands are turning, and it’s all rushing by too quickly to be fully received. Until the witnesses appear, that is, in very long shots, and they are granted a ground and solidity exactly so they can reaffirm, in language, that there is no ground or solidity. That all this will fade and die.

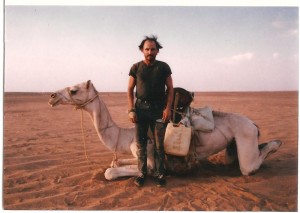

Kristyn Dunnion appears in a nine minute shot, for instance, in her green Mickey Mouse T-shirt, squeezed down into the other end of the couch, while the camera rests on her end table, bringing the crystal vase sharply into focus in the foreground, while she remains on the other side, a little soft, and more than a little hurt, crying out the pain of losing him. Recalling the last time she ever saw him, when, impossibly, he rehearses his own death that would occur only two days later. Flopping on her desk in a parody of dying until she makes him stop, the cool punk queen brought up and over the edge, and then she gets to tell him what we all wanted to tell him. You matter. What you do and how you do it matters to me. She tells him it wouldn’t be worth living in the world if he weren’t in it. Which he takes, somehow, as an invitation to depart because there is nowhere for a sentiment like that to stick to him. There is no shelf to put it on, no bell jar it might be kept alive in, not even for a few more days. Instead he takes his curtain call, “Oh thanks,” and with a whisk of his scarf he is gone. Well hung and snow white tan. How did Paul Celan put it? The hanged man chokes the rope. Perhaps that’s what the movie is really about. To show how you practice your death in front of your possibly best friend who steps up and tells you exactly what she’s supposed to say and then you go right on ahead and hang yourself. Dying. Everyone and everything can’t help themselves from rushing towards their death, and perhaps by finishing the movie I hoped I could hold that up a little. Perhaps I even wanted to make a movie that would kill death, the way that Frank Cole did. He wanted to call his last movie Death’s Death. Such was his conviction that he crossed the Sahara by himself, along with a few trampled camels.

“The reason why I crossed the Sahara Desert by camel had to be kept a secret. I will explain why, later. The Sahara Desert is 7,000 kilometres wide and took eleven months to cross. I was thirty-six: young, extremely fit, extremely determined. For now I am only going to explain that I did it to prove something. I could prove it symbolically, not scientifically, because I am an artist not a doctor. But I believe that symbolic proof might inspire others to discover scientific proof. Nothing is impossible… Mom, I am trying in my own way to keep him alive. When you asked for my help to bury Gramps’ ashes, five years after his death, I secretly kept a vial of them. I never told you because it would have hurt you. To know that I still couldn’t let go of him…There is no difference between an animal and a man. I realized this the day my dog died. It was my first experience of death. I was ten and stood crying as my mother and father buried him in the backyard. There was a group of people watching from next door. One of them came over and wanting to comfort me, asked if I would like to say a prayer? I screamed, horrified, until he went away. Did he think I was going to pray and thereby show acceptance? I was beside myself with grief. Never before had I felt such grief. And I was stunned by how my dog looked before he died. He smiled at me, and I had suddenly realized how human he looked. No one gathered there tried to comfort me again. Even my mother and father realized it was impossible. They knew I was never going to accept his death. It was from this moment on that I was never going to accept any death at all.”

Refusing death, he crosses the Sahara, chanting to himself with every footfall the opening four words from T.E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, “I loved you so…” and then adding, “dear gramps.” For eleven months. How far does one need to go to create a picture? To create montage (not the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table but: his death and my life). The “secret” that Frank is keeping, that he whispers at the head of his year long diary, drawn out in exhausted entries at the end of a day’s trek, is that he wants to defeat death, at least symbolically. Surely, if a man can cross the Sahara Desert alone, then death itself can be defeated. Can’t it?

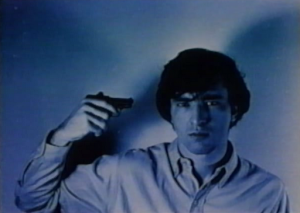

Frank survived his miserablist crossing, and then he went back to do it again, and was jumped by bandits in Mali and murdered. Perhaps he was also looking for a mission when the Sahara called, and once he answered, he couldn’t keep it from calling again and again. Until death do you part. Paul Sharits made a movie called T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968). It is thirty six minutes long, a hyperbolic six-sectioned short featuring intensely flickering solid colour fields, which are occasionally interrupted by single frames of an eye operation, a close-up of intercoursed genitals, and poet David Franks holding a pair of scissors around his tongue. On the soundtrack one can hear the word “Destroy” repeated again and again. The hope, as Sharits named it then, was to “destroy destruction.” I think one can hear, in this needful mantra, an echo of Frank’s inclination to kill death. Here is Sharits in his own words:

“I’ve given the impression at times that meditation itself was a major formative and generating source for the mandala films, but another reason they have that form is the magical aspect. This is not magic as Crowley would define it, this is a more personal sense I have that we make things, and if they’re devoid of normal usage then it’s possible, if they’re structured in certain ways, to have other effects. They have other usages that I can’t define exactly, but would name “magic.” I don’t mean magic in the “magician” sense of conjuring up an illusion. I mean an object, or an experience, that is charmed. One traditionally charms objects by making them oneself, or at least acquiring the materials oneself. This is one prerequisite of magical objects. And although you may be using very classical principles, another thing that’s important is your intention, which is an invisible quality. You really have to believe, and belief can’t be measured except in the effectiveness of the experience.

I don’t mean for my films to be magical to strangers. In many ways, I direct them to people that are close to me. I understand that Harry Smith at one time did not care to show his films to the public because he felt they were magical and were addressed to people he knew. I don’t know if you can address this kind of magic to strangers. I don’t know if film can do those kind of things to people that you don’t know, care about or think of while you’re making the thing; because part of the ritual of construction is intention. Piece Mandala/End War has a great deal to do with the relationship with my wife at that particular time. We are separated now, but at that time we had been separated for a short while and we got back together. Then the form crystallized for me: how could I make a film that would have a magical effect in our relationship? The film is dedicated to her.

There’s an image in the film of me shooting myself, that is also un-happening. I don’t what suicide is like, but there are other forms of suicide that I’ve practiced in my life that allow a rebirth. They’re not pleasant, I think of them as a form of death. Giving up whole frames of reference. One evening in the country, in the company of several very close friends, my wife and I performed a ritual of throwing away the charmed objects of our marriage. This was an event that my wife programmed for me to understand her frame of reference, so we threw away our wedding rings. What we were trying to do was find new levels of coordinating our relationship and get more intense.

A film like T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G is trying to negate certain forms of negation in several people, including myself. This film is directed towards a couple of other people who, like myself, are self-destructive. I wanted to frame this for us to study and respond to. The dedication of the film has never been formally accepted, and I believe it has been informally rejected by my brother. I don’t know if he’s seen the film or not, that certainly isn’t the level on which the acceptance or rejection would occur. But it was a film for him and for the people in it. The main image shows David Franks, a very close friend of mine, who I think is a very fine young poet, and his – how shall I say it, we have to be careful about this on tape – his lady at the time. She appears in the film scratching his face. It was a very intense occasion when we filmed this. Of course she didn’t really scratch his face; we applied streaks of glitter to his face, but we had to do it in such an intense psychological manner that she fainted. I became very incensed and had to transcend my personal feelings to care for my friends and insist, absolutely insist, that she get back and hold this posture properly, and become almost trance-like while shooting. It was a very intense occasion, part of the process of charming and investing the object-film with these intentions and vibrations, and so forth. Although it’s been condemned at times as being a sadistic work, I feel that the film essentially has to do with healing. It’s anti-sadistic.” (Mental Funerals: an interview with Paul Sharits by John Du Cane and Simon Field (London, 1970)

A cinema of magic, made for a handful of familiars, a closed circle, a private ritual. Is that too little to say? Or too much? To try to put an end to endings, to destroy destruction, “to negate certain forms of negation in several people, including myself.” How’s that for the intentional fallacy? Or this one: “I wanted to frame this for us to study and respond to.” Do I even need to add that Sharits is now dead, and that he died by his own hand? Perhaps, by making this movie, I am trying to grant myself a little “extra time” that all of my dead friends won’t enjoy. Though mostly I am busy, like Frank and Paul, laying down with the corpses. Three years has been a long time to spend inside Mark’s coffin, and there has been more than a little doubt that the lid would be ever be lifted, or that if it would be, the person who crawled up out of there might be hardly recognizable. I would like to name this movie as the lifting of that lid, though it is also the graveside vigil, and then the dying, and then trying to kill death, or to unkill myself. I watch the bullet that pierces my heart leave me in reverse slow motion, the exit wound in my chest closes around the impact, the shreds and shards and blood fall back into my body, the bullet returns to its warm chamber. And here I am again, answering questions. Who are you again?

Jason: “In the place which can’t be borne, speaking words which can’t be spoken, feeling only that which cannot be named.” I think this is what is known as the empty place of trauma. This is exactly why I think appeal to the ‘Symbolic,’ to psychoanalysis, is the wrong approach. The form that recollection takes might be a representation, but the rhythm is just that, like a felt pattern, a vibration, an intensity. The editing is the ‘something else’ that isn’t reducible to the inter-subjective formalization that is language. Editing asks a question, makes a fissure, indicates an empty place — the space around hands moving in the air, complicating what is being spoken. I absolutely agree. And when I say spoken, I don’t only mean with words, but with whatever formalized vocabulary…

“Why make anything at all in a world already too full of it?”

This is your question not mine. Mine was: what is the goal?

“The immediate goal for Mark’s movie, though, was something much more modest. To be able to share something of my experience of Mark to those who didn’t know him. Call it translation. Or ventriloquism. Is that enough? Perhaps for someone, sometimes.”

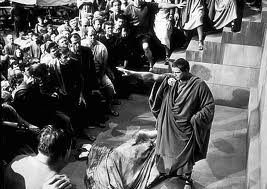

And there it is, the goal. Metonymy… The encyclopedia Britannica allows this on the matter: From the Greek mesa “change” and onuma “name,” a figure of speech in which the name of an object or concept is replaced with a word closely related to, or suggested, by the original, as “crown” to mean “king” (“The power of the crown was mortally weakened.”) or an author for his works (“I’m studying Shakespeare.”). A familiar Shakespearean example is Mark Antony’s speech in Julius Caesar in which he asks of his audience: “Lend me your ears.”

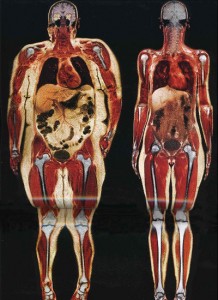

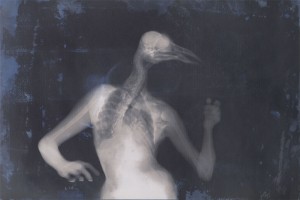

Metonymy is closely related to synecdoche, the naming of a part for the whole or a whole for the part, and is a common poetic device. Metonymy has the effect of creating concrete and vivid images in place of generalities, as in the substitution of a specific “grave” for the abstraction “death.” Or perhaps a movie for a life? Viewers count their pictured times in minutes, in totalized running lengths, while makers tend towards frames. How many frames does it take to touch the side of her face? To illuminate the other side of that glass bowl? And how many frames does it require to conjure a life? Perhaps the cinema of biography labours beneath a hieroglyphic fantasy, that any moment can be excised, the moment when a camera happens to be turned on for instance, and that moment can stand in for every unpictured activity. There is your friend Mark chowing a bowl of noodles, and how cleverly you’ve collaged him with an X-rayed skeleton digesting, as if he was swallowing his way towards death. Is that truth thirty times a second? And how many frames is someone’s life worth exactly? Fifteen minutes of fame equals 27,000 frames. Would that be enough to tell the story of your life? Or your friend’s life? I ask already knowing the answer of course, the movie, as it currently sits, is just shy of 70 minutes (or 126,000 frames). How to escape this cruel accounting, the summary reduction that occurs whenever a name is dropped into conversation. Oh him, he’s so… There, I’ve just managed him in one word. And her? She can’t help responding by being so very… And there they are, the unhappy couple. A couple of words, a couple of frames. How to stop this short circuiting? Perhaps by the method you’ve already devised, endlessly revising works until eventually withdrawing them from circulation entirely. What your movies suggest is not a rush to judgment, but a temporary suspension of judgment, followed by a slow withdrawal, until they slip out of view entirely.

What images are on offer that stand in for Mark? The movie opens with a movement underwater, a tangle of boy’s legs, a rush of bubbles, and then swimmers make their way to the surface. This gesture of surfacing summarizes the entire movement of the movie, doesn’t it? Of bringing what belongs below ground into the light. And what do we find when we surface? A picture of your friend in a canoe, massively slowed down. While we are once more at high noon, in the bright light of day, what we are seeing, or what you would have us see, is something like the unconscious.

“With the close-up, space expands; with slow motion, movement is extended… slow motion not only presents familiar qualities of movement but reveals in them entirely unknown ones ‘which, far from looking like retarded rapid movements, give the effect of singularly gliding, floating, supernatural motions.’ Evidently a different nature opens itself to the camera than opens to the naked eye – if only because an unconsciously penetrated space is substituted for a space consciously explored by man. Even if one has a general knowledge of the way people walk, one knows nothing of a person’s posture during the fractional second of a stride. The act of reaching for a lighter or a spoon is familiar routine, yet we hardly know what really goes on between hand and metal, not to mention how this fluctuates with our moods. Here the camera intervenes with the resources of its lowerings and liftings, its interruptions and isolations, it extensions and accelerations, its enlargements and reductions. The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses.” (The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction by Walter Benjamin)

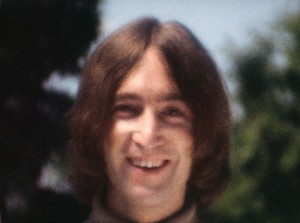

What is being isolated, in this instance, is the look on Mark’s face, which turns from a frown to a smile. How very unlike that rash of Fluxus movies made in the 1960s, like Yoko Ono’s Film Number 5 (1968), which shows John Lennon slowly breaking out into a smile over the course of 51 minutes. Instead, Mark’s into-the-sun grimace turns to face the camera waiting for him at the head of the canoe as he shines his winning smile back into posterity. It’s nothing really, in real time it would be a harmless camera mugging, scarcely noticed, but here, underlined with an opening voice-over riff, it becomes the thing itself. It’s like watching a magician pulling a bird from his sleeve, Mark’s art of concealing is not only revealed, but your voiced captioning suggests that this is his primary mode of presentation. You unwrap him, cruelly and forcefully, before the opening title announces his name, and captions his pictures. But you are never so forthright again, instead, it seems you are content to plunge down below the surface of the water, all of Mark’s unspoken and left-behind darknesses will be hinted at, but never finally unveiled by the rest of the movie. Instead, you make a careful stepping through the landmine of personality, and trace an outline, content to offer us glimpses and impressions, glances in place of stares.

Early in the movie we see him in a rare sync sound moment. He is at home, making a tape for his parents which will show both his house, and himself, to them. After a moment in an indeterminate space, where it is difficult to make him out over his girlfriend’s shower room crooning, he moves to the mirror. In this scene his parents and the mirror stand in the same place. Both make him visible. They show him to himself. But what do we learn of his parents? His father is a shadowy and unspeaking presence, while his mother signals disapproval of his sloppiness and dress, and points out the marks on his arms where he cut himself. Silence, disapproval and the recognition of pain. The father’s brother dead by suicide. Perhaps all this (and how much more?) waits for him in the mirror.

Mike: There are moments in any extended edit session when it feels that two worlds are being joined across a cut. After this impossible, never-before-thought union, nothing will ever be the same again. Or that’s how the fantasy goes. In Mark’s archive I found a tape of a tape showing Mark strolling across a stage at a vegan fashion show. Mirha also lit up proceedings, and I’m guessing that it was her participation that prompted his own. He appears in various guises as the offstage models careen from one costume to the next before taking another turn in the spotlight. It is an unlikely role for Mark, to say the least, and I couldn’t resist pulling out a moment when he is striding in almost-green trousers and suspenders, and with one hand at his hip (had he received instructions? Was he posed?) the other slowly turns at the wrist, as if he was sculling in slow motion water. This small hand gesture says: aren’t I fabulous? Look at me all glammed up!

This runway fragment is dropped into a section of the movie where his mother Zorka talks about his depression and the marks on his arms which were the result of teenage cutting bouts. From this small turning hand the cut delivers us to Zorka’s hand moving up and down her arm. “Do you remember he has these marks on his skin?” How very low he must have felt in order to produce this self-scarring. What the edit insists on is the relation of the low and the high, the self as show business, and the showing of pain. This alternating current is a particularly queer confection, lying right underneath the queer showbiz glam of the fashion shoot there is trauma and shame, those hands baying for attention also wielded a razor, not so many years back. As neighbours, these moments appear as two sides of each other, a necessary union. The more than occasional extravagance of queer pride carries some of this dark freight, and while Mark’s everyday presentation style was more indie punk, the long scarves and lighter-than-air ballet step showed his queer heart at work.

Jason: How does this movie stand in relation to your Song for Mixed Choir (1980) or more generally that other practice which apparently took its cues from canonical minimalism?

Mike: Song was a first step, but not an establishing shot. It is filled with grain turning, the pictures are vague and very much in the background. What has been carried across thirty years? Certainly not myself, I understand that every cell in my body has changed at least five or six times since then. In every important understanding of the term, I am not that maker, and it’s not my movie. But there may be hauntings which continue to shadow the present. For instance?

There are at least two important schoolboy lessons learned in the emptied-out screens of the formalists. The first has to do with waiting. With our new flash digital cameras the prospect of waiting for a picture seems a kind of science fiction of the past. A relic of attention. But while watching Ellie Epp’s Trapline (18 minutes 1976), or Rose Lowder’s Rue de Teinturiers (31 minutes silent 1979) and a thousand other long short movies, I learned to wait.

Here’s what Ellie Epp says about it: “Technically, duration is something quite particular — when you keep seeing something that doesn’t change very much you stabilize into it, you shift, you get sensitive, you cross a threshold, something happens. It’s useful for anyone to learn to do that. It’s an endless source of pleasure and knowledge. And yet it’s often what’s hardest for people who don’t know it as a convention. It’s the central sophistication of experimental filmmakers. We all had to learn it. We probably all remember what film we learned it from. I learned it from Hotel Monterey, which Babette Mangolte shot for Chantal Akerman. Almost an hour, extremely slow. I made the crossing. It was ecstatic. What it is, is this: deep attention is ecstatic in itself.”

Deep attention. I could also sit on a cushion and find the same riffless riff, becoming only too aware of my citta vrtti, the turnings of consciousness that I lay over everything in front of me like a thick slab of chocolate cream. But I learned to wait in that period, so I went over to Mirha’s apartment, day after night after day, after she had put out a general call. Because the unthinkable thing, the thing that could never happen, had occurred in their home, she felt unsafe for a time, and asked if people might come by and sleep on the couch. It seemed the least I could do. And even better, there were dishes to be done and cats to be fed and Seamus, their little Shitsu dog, could be walked. In other words, I might actually do something, instead of just staying at home and feeling worse. And eventually doing something meant bringing a camera around. I asked Mirha if it would be OK if I made some pictures of their things, their books and wall pictures, the small totems of a life together. The cats of course. And as Mirha brought an extraordinary degree of performativity to her everyday life, it quickly became clear that she didn’t mind having a camera around at all. On or off screen, she always spoke with an astonishing and accelerated candour. I recorded over many months, with absolutely no goal in mind. There were no scenes I was trying to put together, and we never sat down to do a formal interview. I would come and hang out and do some more dishes and sometimes I would shoot and sometimes I wouldn’t. I was waiting. The work was waiting.

The second lesson was about light. The way light strikes the side of a face or the edge of a table. What began happening with Fascination, my sideways biography of Colin Campbell, is that I started shooting again, after years of working mostly with found footage. And what I was shooting, most of the time, was light. Though this light might appear in different guises. Like an icy view out a train window. Or Esma’s hands on the curtain. Or Thomas sitting beside me on a bus trailing the outskirts of Mexico City. There are moments running through this movie, many taken with my nephew, where this formalist disposition rears up again and again. Of course, none of that makes Mark any more real, perhaps it is only a habit, an aping mechanism, though it helps contribute to what you named as the work’s “ass loads of beauty.”

But how does a movie filled with grain turning about the screen relate to a portrait of my friend? I feel I am coming out of a tradition which has been consumed with the signifier, with a meticulous examination of how meaning is made. This orthodoxy is still well represented almost anywhere the term “avant-garde” film is deployed, which has become a genre denotation, like science fiction or film noir. The emulsion fetishists, the emphasis on hand-made and first-person everything, the authorial presence, the eternal themes (memory, absence, time…), the sense of a tradition reasserting itself, the codes of production (pass the Bolex please), all this is familiar. And while there is still beautiful work being done in this arena, it is not where I am, it’s the home I’ve already left behind, though it continues to mark me.

For the past dozen years I have been working in video, and materialist reflections seem less relevant, perhaps because of friend’s deaths which suddenly render all-night materialist excursions less pointed somehow. Editing video occurs via computers which convert material tapes into immaterial timelines and flows, and likewise “video” itself is a catch-all term for whatever is sparking pictures this week, whether it’s high 8, dvcam, beta sp, or the multi-headed format universe known as “high definition.”