(check out Janice’s chops at: www.janicecole.com)

From Frank’s Cock to Imitations of Life: Ten Years With Mike Hoolboom by Janice Cole (Originally published in POV Magazine Issue 52, Winter 2003/4)

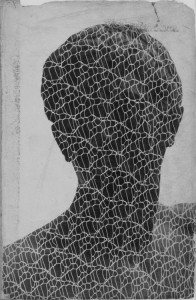

He’s a cultural anthropologist, a staunch memory archivist—an experimental documentary and narrative theorist. He scours his roots, his life and his personal health to propose ways that we might contemplate our own roots and lives and how to revisit perceptions of AIDS. He was diagnosed HIV+ more than a decade ago and since then his volume of work has increased monumentally as has the urgency in its content. His outpouring since 1993, of both feature-length and short films, belongs to a man stacking up copious amounts pending uncertain future productivity. At the same time, Mike Hoolboom has miraculously achieved the rare accomplishment of creating a unique cinematic style that certainly assures him sempiternity.

Frank’s Cock (1993, 8 minutes) is a weighty proponent for augmenting the viewing of the short film form; not by merely preserving shorts, but by celebrating, promoting and making them far more accessible to audiences than alternative art house screenings, film festivals and limited television programming presently allow. This extraordinary experimental documentary relies on a text of wit and candor to present a heartrending story, complete with a dramatic twist and emotional punch. By expertly applying traditional screenwriting practices to his trademark adept text, Hoolboom lifts an otherwise linear structure to an extraordinary vantage point.

Hoolboom wrote the narrative based on someone else’s actual experience and he lets the story unfold as a hot attraction, then shifts to tragic loss without exposing a seam in the transition. He allows us the power of the main character’s facial expressions and throws in a lyrical triad of simile to chew on. The result is stunning. The film essentially relies on a straight-to-camera monologue, (occupying only the mere upper right corner of the frame). Introduced at various moments throughout the monologue are well-chosen images representing human creation (upper left), popular art (lower left) and graphic gay porn (lower right). By splitting the 16mm frame into four sections, the multiple layers of imagery support the text, but the deeper strength of the construct comes in fleeting moments, when individual quadrants inadvertently flow in-or-out-of-sync, creating an optical treatment purposefully grounded in both dream and reality.

We’re introduced to Frank’s (unnamed) lover, played perfectly (by then unknown) Canadian actor Callum Keith Rennie. He begins his monologue by recalling sexual copiousness starting when he wanked off as a baby and continuing through aspirations to be the “Michael Jordan of sex” or “Wayne Gretzky of hard-ons.” His lustful yearnings come to fruition when he meets Frank. Having warmed us to his lurid backstory, Rennie now makes us privy to completely affectionate, conscript details about his drop-dead allure to the one-and-only Frank who opens beer with his teeth and makes omelettes the size of a man’s head. These precisely pointed idiosyncrasies present Frank as both macho and nurturer in the same body, without wasting a word, an image, or a second of time. In mere minutes the narrative has successfully set up an audience to main character connection, making them cognizant of Rennie’s draw to Frank, and hooking them, so they’re ready when he meanders into the wonders of Frank’s cock and details of intimate romps. In particular, Frank likes to pick a day on the calendar for sex, and he expects to go at it for the entire day. (Is there a person in the audience-gay, straight/bisexual, male, female or transgender—who cannot relate in some way to the raw power of this male-male attraction? Likely not, which is a remarkable feat).

Once the audience is deep into their web of attraction, which is crucial for the twist—the narrative effortlessly glides into Frank’s weight loss and other symptoms from AIDS. My throat dries as I contemplate the impending loss of Frank, and the certain emptiness his lover will hold in the absence of holding him. The main character suggests that “nothing has changed, except he’s (Frank) dying.” Not spoken, but clearly implied is the certainty that everything has changed, irreversibly.

Frank’s Cock is as bold as the title implies, celebrating homo-erotic sexuality in the realm of AIDS rather than simply condoning it the way mainstream films tend to do. Hoolboom’s short essay packs more dramatic effect than feature films like Longtime Companion or Philadelphia, both of which have been widely broadcast on television. While I can sit through twenty movies on TV to screen a hit, twenty series of find a good one, twenty music videos to watch a gem, opportunities to find exquisite shorts on television aren’t as readily available. Why not run short films during prime time, on national broadcast? Frank’s Cock is a ripe candidate as the airwaves open wider.

Not all of Hoolboom’s experimental work falls into the short form category, but it’s primarily those pieces, and in particular Frank’s Cock and Letters From Home, that make him a prodigious Canadian filmmaker of alternative documentary and narrative cinema. Letters From Home (1996, 15 minutes) uses a narrative text that is based primarily on a speech by Vito Russo, with additional writing contributions from Hoolboom. While Frank’s Cock starts with romance and ends with death, Letters From Home dispels the AIDS death sentence and swings open the door leading to romance. This time Hoolboom works with a non-linear narrative in multiple voices—male, female—and ultimately universal. The text is delivered in fragments that are part story, part confessional and part spokesperson. The filmmaker briefly appears before the camera to inform us, “I’m a person not dying of AIDS, but successfully living with it.” A different off-screen male voice tell us, “Reports in the media would have you believe two things: that I’m going to die, and that the government is doing all they can to save me. They’re wrong on both counts.” But it’s a monotone female voice that delivers the most powerful spark to dispel stereotypical myths: “If I’m dying of anything it’s the way you look at me. It’s from the harsh cleanser you put on the toilet after I’ve used it.” The subtext of this powerful passage implies that not only do people in general look at HIV and AIDS through smoke-stained glasses, but indeed, people supposedly in-the-know about the illness possess tarnished views as well. Hoolboom’s choice to have a woman deliver these lines effectively doubles their impact.

At this point in the narrative a different off-screen voice boldly declares, “One day the AIDS crisis will be over,” and then, perfectly timed, we witness a quiet interlude of two men passionately kissing. The voices cease, allowing the audience to fully digest the pure power of their intimacy. And it’s during this well-placed interlude that the audience gets a chance to put it all together—being diagnosed with AIDS is not a death sentence—life goes on, life includes love includes sex, and sex reminds us that we’re very much alive. Callum Keith Rennie concludes the film, and his appearance forms a bookend for the two shorts. The economy of narrative and abundance of story in both films is extraordinary.

Over the past decade, Hoolboom has interspersed his short works with an uncanny number of experimental features, including Kanada (1993), Valentine’s Day (1994), House of Pain (1995), Panic Bodies (1997), Tom (2002) and Imitations of Life (2003).

Tom Chomont, a New York avant-garde filmmaker, amassed more than forty personal-diary films since the early 1960s, many of them a mere minute or two in length, and a large portion having no sound accompaniment. In a different filmmaker’s hands the documentary tribute Tom (2002) could have been a typical bio-pic about a noteworthy artist, but given Hoolboom’s visually stunning experimental treatment, it is raised to a more cerebral contemplation of themes with a deeper emotional connection to subject. The documentary uses Tom’s words and images as a base, and introduces us to Hoolboom’s familiar layering of visuals that wash through various recalls of his life to expand our thoughts and feelings about the artist being immortalized—and take us to places of universal concern.

A segment that stands out has Tom confessing to early sexual experimentation with his brother, explaining candidly how they explored each other three times and then “went back to being brothers again” (and offering no conclusions about their feelings for each other when the incestuous acts ceased). Later in the film his brother is dying of AIDS, and Tom, who is HIV+ himself, cannot hide his despair at this event, nor can he conceal any longer an ongoing idealization of his brother which has never dissipated, but which he’s managed to keep silently parked all these years.

There are images from Tom’s films, shots of him dressed in leather and in drag, and sequences of him traipsing through the memory banks of a rich life that will inevitably end before its time. Tom acts as a reminder of similar countless young men whose lives have been cut short, mainly from the epidemic of our times, and it heightens each of these lives by subtle comparison.

When I’m introduced to Tom’s image in the opening shot, he looks ill, and I subconsciously imagine he’s living with AIDS. While it’s true he is HIV positive, only towards the film’s conclusion is it revealed that Tom is also battling Parkinson’s, which, in Hoolboom’s style, effectively dispenses myths about who owns which disease. The abstractly lyrical, yet ultimately powerful feature documentary is a homage from one artist to another, and a continuing example of Hoolboom’s commitment to dispelling AIDS parables.

Imitations of Life is Hoolboom’s latest feature and most ambitious film. The experimental, theory-based documentary narrative was recently showcased at the 28th Toronto International Film Festival (Hoolboom has had more films programmed in Perspective Canada than any other director and he’s twice picked up the NFB short film prize at TIFF).

In Imitations of Life , Hoolboom sets out on a journey of discovery, a voyage into the perspective and ownership of memory. The result is a lush and often hypnotic experimental-doc in ten parts. Of the ten segments, most work on their own while others are not as complete, but each has individual strengths that when strung together build an exquisite overall viewing experience. The cerebral diary-essay is satisfying and some moments are truly extraordinary.

The film opens with a shot from Citizen Kane , setting the stage for what’s to come in a film relying heavily on “borrowed” film clips, everything from early cinema and classics to movie stars and modern sci-fi. Hoolboom weaves two themes throughout Imitations of Life —an investigation into the ways that portraits and movies shape memory, and a search for ways that we as humans shape it. In an early sequence aptly named Jack , he demonstrates both themes quite nicely by constructing a personal diary of his nephew, Jack Daniels Fuller. He narrates the passage and accompanies it with home movie footage he’s amassed of Jack, so that we contemplate the innocent child while digesting the adult narrative. Hoolboom causes us to believe that Jack is imagining his future, as only he can, while simultaneously demonstrating that the camera can flagrantly claim ownership of Jack’s past. In The Game, the filmmaker again takes up personal reflections, this time about a game he and his sister played, suggesting that in their youth they held the future inside them like a bomb (i.e. already performed, not yet revealed).

Scaling has two male nudes juxtaposed, situated horizontally in frame rather than vertically: one paints a wall while the other undoes the paint job. A young boy speaks in fragmented thoughts, suggesting that “The past is a foreign country never visited.” thereby implying that humans don’t own the ‘true’ recall of their past, and supporting the ongoing theory of documentation as memory ‘truth.’

Imitation of Life, which is a stand-alone section within the feature, surveys a theoretical prognosticate of memory by letting the past collide with the future. The filmmaker suggests that ‘movies mark the passage of time,’ and then asks us how we will invent our future. Ideas of documentation forming our past and human invention forming our future are thought provoking, but also serve to remind us that time markers are drawn from sources beyond documented ‘truths,’ and future are not necessarily found on acts of invention, but rather on the lack thereof.

Rain is the final segment in the film and the most beautiful to watch, prompting me to seek the source of the absolutely gorgeous slow-motion footage, but alas, while editing credits are readily available, the established pattern of showing no credits for the source of footage continues. Did Hoolboom shot the footage, or borrow it? The use of appropriated material raises issue to ponder far beyond Hoolboom’s body of work. For instance, how does one distinguish the fuzzy line dividing ‘critical reinvention’ and ‘visual accompaniment,’ or set the boundary to characterize the context between ‘free’ and ‘cleared’ use of images? The creative and legal specifications guiding the re-use of material seems to be an ongoing question.

Imitations of Life draws on popular movie clips, and uses them liberally, along with found footage, original footage and stunning archival shots of global experiences and mass communication, presenting viewers with a mesmerizing carnal collage. To digest the words of the various sections, and interpret their meaning, it’s sometimes pertinent to understand sources of accompanying visuals, which, to all appearances, were chosen to help assimilate the lyrical, theoretical, diary-essay prose. As the filmmaker’s lens increasingly declines to the looming lens of appropriation there is room for abstraction. It’s precisely because his message is engaging, and his narrative so strong, that I yearn not to get lost in the mental exercise of calculating image sources and subconsciously wondering why he has chosen obvious or not-so-obvious appropriations and purposefully accompanied them with certain passages of text. The visceral appeal of the film works wholeheartedly, but the psychical meaning can cloud, yet the film is sure to have differing effects on different viewers because it is so densely layered. And undoubtedly, this is to some extent what the filmmaker sets out to accomplish.

Documentaries are often scripted in post-production, making them more weighty to construct than dramatic narratives which are generally scripted long before pre-production, and the task of scripting experimental, personal-diary, lyrical-memory or theoretical-essay narratives can be the most arduous. Hoolboom is among the genre’s most prodigious filmmakers, producing engaging films that succeed in provoking empathy and pathos.