Philip Monk curates Filmmaker Mike Hoolboom’s inaugural museum show, The Invisible Man, at the Art Gallery of York University

Posted by Carla Garnet at Thu Jan 27 09:52:13 2005

Over the past forty-five years video as an art form has expanded to embrace single-channel videotapes, video sculptures, cinematic installations, plasma screen presentations and multi-channel DVD projections. Gallery installations by independent film and video producers have precipitated numerous viewing innovations many of which are employed by Mike Hoolboom’s 3-part installation entitled The Invisible Man, curated by Philip Monk on view at the Art Gallery of York University.

The gallery setting allows this filmmaker’s complex combination of camera images to create associations between time and space and the viewer’s body. Hoolboom’s exhibition asks that the viewer become involved with content and context, requiring visitors to reflect on their precise location in relation to the work’s locus. The Invisible Man, illustrates a statement by Margaret Morse (author of Video Installation Art: The Body, the Image and the Space-in-Between): “It is the visitor rather than the artist who performs the piece in an installation.” For that reason context is critical to Monk’s curation of Hoolboom because it is the gallery that allows the filmmaker’s work to function more like sculpture than film.

Upon entering the AGYU our attention is drawn to Hoolboom’s black and white DVD-loop, In the Future, created from a montage of Hollywood film, found footage, and home movies. In the Future is presented on a flat, horizontal, plasma screen that is cleanly inserted into an otherwise unblemished white wall. The audio component of the first work disarms the visitor, who is still struggling to un-encumber their bulk of winter’s necessary clothes. It is a child’s voice that breaks through reverie with, “Last night I had a dream: that the movies I had seen even in the womb were a prophecy. They were my future.” Beleaguered by more layers to be peeled off and then to be later reapplied, gallery-goers are reminded that while the artist’s bodiless articulation has the power to break through private day dreams, as spectators, we will have to take in Philip Monk’s curatorial presentation as corporeal beings. Driving the point home an AGYU attendant hands out the exhibition map, propelling viewers forward.

Mike Hoolboom is primarily known as an experimental filmmaker who urgently conveys the contemporary relationship between life, death, sex and the movies. In this respect, the AGYU’s show of Hoolboom’s oeuvre, The Invisible Man, is no different. Without directly saying as much, Monk’s installations of Hoolboom’s projected works ask us to reflect on several of Walter Benjamin’s seminal questions. How cinema has altered our relationship to life experiences? What are the ramifications of film (and photography) on art? Has mechanized copying freed art from its reliance on the ceremonial? Has the purpose of art been inverted? Has cinematic experience impacted on the optical parts of the mind that contain memories, thought, feeling, ideas, and the unconscious? Does the physical experience of viewing Hoolboom’s filmic work as installation interrupt the dream state often associated with the cinema experience and make us conscious of it?

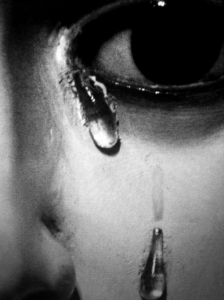

In order to take in the next work, from which the show takes its title, the map tells visitors we must walk through a narrow darkened corridor into a sizable room where a projection of The Invisible Man competes with a 3-monitor tower for our attention. As spectators we are conflicted, which way should we look, at the luminous projection or at the three small televisions? Our attention races between the cinematic black and white projection that occasionally blooms into living colour, and the phallic television tower. The artist’s voice intermittently pierces through the hypnotic passage of images and symphonic soundscape. His projections refer to themselves, light projected through windows, doorways, rising and setting with the sun, forged in the heat of a volcano, shone from lamps, flashlights, nightlights, expunged into darkness and reborn as daylight effectively turning the gallery into a giant strobe and beating heart.

Informed by the map, viewers are made aware that there is one more Hoolboom work. We read that this cinematic piece is a meditation on living in the fields of the future/past, accessed through the shared picture world of movies, where substance dissolves and bodies evaporate. It is entitled Imitations of Life. Accordingly, visitors move through an institutional door into another dark space. This action functions as a double crossing over from a projected threshold through an actual one, the double entrance implies a double exit.

A word caption emblazes momentarily across a large flat light-informed surface. It reads, “IN THE ‘TERROR TO REMEMBER’ HOW WILL YOU INVENT THE FUTURE?” Witnesses are keyed to think, “there are so many cinematic versions that already exist.” Science, cinema, and art merge on screen and in the synthetic space between the viewers and the viewed. The installation is a loop that plunders the body of cinema for an epic that contains a dominion of dislocated fears and dreams, a place to imagine a future that is already here and that we must pass back through in order to reach the end/beginning. In the process of taking in Monk’s presentation of Hoolboom’s installation, gallery-goers are transformed; our unconscious thoughts arrive on the surface.

Video installations on the whole are as much about technological change as they are about changes in artistic fashion. As soon as artists became interested in video, they tried to work with the image as a sculptural element, but as a filmmaker, Hoolboom has been resistant to exhibiting in galleries, so it is important to acknowledge that The Invisible Man results as a consequence of Monk’s curatorial intervention. In this exhibition, the gallery-going experience functions as a passage. If indeed, we are sleepwalkers as the show implies, it is we who have performed Philip Monk’s sculptural installation of Mike Hoolboom’s The Invisible Man.