Very much an original work, defiantly passionate in its own right, Mike Hoolboom’s four-chambered (like the human heart) film, House of Pain, has a clear lineage reaching back to Un Chien Andalou, Jack Smith’s notorious creatures and the early high-contrast works of Franz Zwartjes, as well as the episodic, apocalyptic and poetic prose of Les Chants du Maldoror. And like those works, if not more so, the immersion in body fluids and blurred lines of sexual identity, (symbolic) mutilation (especially the metaphorically charged removal of an eye in two episodes – reminiscent both of the infamous Georges Bataille novel L’Histoire d’Oeil and the Samuel Beckett short metaphor for cinema itself, Film, with Buster Keaton), imagery at once grotesque and erotic that seems calculated to outrage and shock any sense of propriety… and, yes, like those works, if not more so, the overall effect of House of Pain is profoundly spiritual.

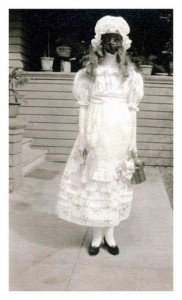

The figures who populate House of Pain’s rooms and landscapes are ultimately identified (in the closing credits) as Angels and their appearances are surely as awesome as the fearful messengers of Ezekiel and Revelation. They are often surreal apparitions of theatrical artifice, layers of make-up and corsets, petticoats, boots and veils or at the very least given an aura of artifice by the harsh contrast, the expressionistic shadows and wide-angle distortion of the filmmaker’s single-eye vision. In one sense, the detached eyeball represents the camera, and the eyeball planted firmly in the body’s head represents both the filmmaker’s and the viewer’s engaged or impassioned view of the subject of the camera. It is the relation between the two eyes that imbues the image with charged meanings derived from a canny use of film stock, lens distortion, the contrivance of choosing what to place before the camera and the sense of syntax which connects discontinuously filmed images into a whole.

The film begins, in Part 1 Precious, with a lone figure which, while exhibiting a large male member protruding from under its skirts, appears to be female. In Part 4 Shiteater, the film returns to a lone figure, who while applying much make-up and veils, appears to be male. The two middle episodes (Part 2 Scum and Part 3 Kisses) describe two forms of pairing, the first a marriage (male and female separated and united), the second a series of three pairings involving a young man first penetrated by an angel reminiscent of the opening and closing figures (that is to say, aspiring to a terrible androgyny) and then bound and flayed by another man and finally encountering a playmate.

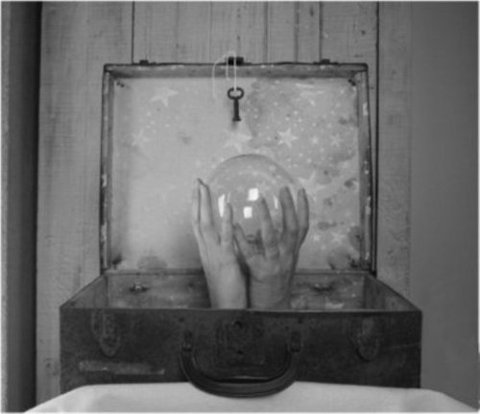

Precious establishes both the body’s obscenity and the body’s spiritual nature. Ethereal light shining directly into the lens and then reflected on water suggests glimpses of divinity at the opening and closing of the episode, but the middle portion describes the angel’s sojourn in a cemetery, lingering over a headstone inscribed ‘Precious.’ The headstone might be taken as a symbol of the fleeting nature of earthly existence as well as the sentimental attachment of the human soul to this transience, but also suggests the more lasting effects of that attachment and its profoundly spiritual nature. The angel confronted with the finality of death produces an enormous erection which it burrows into the earth, while detaching an eyeball which it inserts, and then secretes from its vagina, reinforcing the ancient ritual of rebirth which this opening proposes and which the film at closing completes.

While Precious ends with a hermaphroditic angel absorbed (dissolved) into water reflecting light, Scum begins with a traditionally defined female and male seen in formal wear and descending the steps of a church. This suggests a wedding of man and woman. The man is seen removing his turds from a toilet and smearing himself ecstatically and later the woman wakes and squats over the man’s open mouth filling it with her shit. In intercut images she is seen wearing a bouffant petticoat which somewhat echoes her hairstyle and riding a bicycle through long-shadowed, paved landscapes (calling to mind the man decorated with a hip skirt and collar riding a bicycle in Un Chien Andalou). The underlying ideas here are marriage as unification dissembling into a transaction of material possession, feces being the original material possession apart from the body/self (ie. filthy lucre). In this sense, the generous mouthful bestowed by the bride is her dowry. A sort of unity is accomplished when the woman removes one of the groom’s eyes (like the opening angel) and after baptizing it in urine offers it to him.

Kisses suggests the greatest sense of physical violation but actually emerges as the most tender and childishly playful of the four parts. The protagonist of this episode suggests both a marginal social outsider and the artist as outsider. He is introduced among refuse and debris on the outskirts of an urban landscape, eating from the detritus and earth he is crawling through. A second figure reminiscent of the opening and closing angels, bedecks itself in front of a theatre makeup mirror (a ritual echoed by the angel of Part 4) before coming upon the protagonist lying as though in slumber on a railroad track. After images describing the angel’s rude penetration of the inert protagonist, the protagonist is seen making a spray-paint outline of his body on the ground. This proposes both the creative endeavor as a stepping-back to regard even one’s own presence (as with the detached eye) and as a marker of a lived experience. The body of the protagonist is an unmoving object during the event but comes to life in creating the marking of the event. The ritual nature of the dressing up and initiation are advanced in the next encounter which describes the protagonist tied up and hung by his ankles, then cut open. But when he is let down he is embraced by his torturer tenderly and the film’s function as a negotiator of fantasy and rebirth is underscored. In the final sequence of Kisses, the protagonist encounters a stranger while pissing in the hall of an abandoned and dilapidated industrial/institutional building. Among much menacing approaches between the two men, the protagonist shaves the other’s head with an electric buzzer and the two are intercut romping in a children’s playground. This third part to the film suggests a less apparent androgyny and connects art to the ability to transcend the physical and celebrate the spiritual through it, to reconnect with the childhood trust that allows the spirit to be fluent in speaking through the material world.

The final part, Shiteater, resumes the theme of art and the creative act as a spiritual transformation of physical matter. It reiterates the theme of theatricality (make-up and costume) as a sort of androgyny, but the appliance of simple devices to the face and body take on a suddenly frightening distortion of identity. Feces is again seen as material possession of the other, but the feces itself is here outrageously profuse and baroque and the eating of it is most overtly an exhibitionistic and defiant act. The lone figure in this episode performs a ritual of dressing up before going to the toilet and shits looking the camera sometimes directly in the eye. The episode ends with the angel again returning to water which again and most beautifully reflects bright glows of light.

The artist transforms material including self in order to express the inner spirit, just as the material world is a transient, messy moist and putrid place which also manifests spirit, from which it arises. The film’s title recalls the operation room in which Dr. Moreau transforms animals into humans in Island of Lost Souls and which he calls ‘The House of Pain.’ The title thereby likens the artistic endeavor to render the physical spiritual and the spiritual physical. Both accept and transmogrify the body to the surgical manipulation of the body by the renegade doctor. By exaggerating the nature of physical presence and bodily functioning while rendering it in images which by their heightened contrast and stylized assemblage assert the metaphorical nature of representation, House of Pain is like shock treatment for the sensibilities that prevent us from confronting physical reality in order to appreciate its spiritual nature.