Images Festival Catalogue 1995 (first retrospective)

Images Festival Catalogue 1995 (first retrospective)

reprinted in: Take One, 4:9 (September 1995): pg. 22-7

“My skin is the place where I stop and something else begins.” Kanada (1993)

I suggest we begin at the end: at the border that offers one way to understand one of the most complex and prolific bodies of work in contemporary Canadian cinema. Since Mike Hoolboom began making movies with his father’s super 8 camera, he has demonstrated a consuming interest in navigating the outer limits: of perception, of language, of self, of mechanical reproduction, of bodily sensation and experience (and, most recently and surprisingly, of the discourse of nationhood).

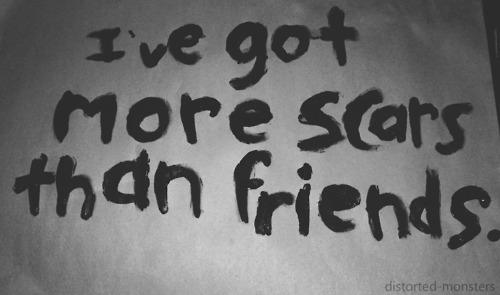

To ask the questions he asks is to exile oneself to the margins; to be consigned to the cultural periphery reserved for those who stretch the limits of common experience: the criminal, the insane, the addicted, the dying, the avant-garde artist. The “experimental” filmmaker. The fact is that most forms of mainstream cultural expression inhabit a non-reflective comfort zone, from which anything marginal is so distant as to be invisible. Which is the catch of such an artistic calling: to traverse the margins is to choose to dwell there, from far the centre.

Consider the terms we use to contain a rudely uncompromising sensibility like Hoolboom’s: avant-garde, radical, experimental – terms which preserve a notion of normal cultural practice while locking their referents outside of it. To experiment is not only to tinker around on the margins of some more fixed and monolithic entity; it implies a perpetually unfinished and frivolously inconsequential activity that never yields results – which is presumably fine by the self-indulgent wankers who engage in such experiments.

It’s this dilettantish connotation that most maligns an artist like Mike Hoolboom. Looking back from this particularly busy intersection of his life and art, one sees as many results as one does experiments. But our cultural language doesn’t allow for the possibility of such results – for that would compel us to invite artists like Hoolboom in from the cold. Instead, he’s had to learn to hammer ever louder on the door of mainstream cultural practice.

Language – which Hoolboom deploys and deconstructs with such imagination – has become a refuge for the culturally marginalized, who have unsurprisingly learned to forge an armour of critical discourse that functions as yet another border separating them from mainstream comprehension. Critical discourse keeps the same distance from the middle as the work it engages with – a development which again serves to exile and isolate. Lacking the proper language for the interpretation of avant-garde work, mainstream critics – like myself – rarely venture to discuss it, leaving it instead to those whose words patrol the border between the middle and the fringe.

To approach Hoolboom’s work is to wade through intimidating thickets of language. Venture towards 1985’s Book of Lies, in which Hoolboom uses black frames to distend and reconfigure an airline commercial featuring a diver, and try to disentangle your bootlaces from Jack Rusholme’s rhetoric in the astute but burdensome How to Die: The Films of Mike Hoolboom. “Here the body displays itself as an attitude of parts, broken by a machine-made compact of representation, its gestures of ascent subject to a narrative gaze of tumescent arousal and deflation (emblematized by the climber’s rise and fall) and viewed as an accumulation of fragments.” Who could fault the uninitiated for heading back to the Cineplex?

In the same way that he is able to juggle the prosaic with the esoteric in his work, Hoolboom vaults between the colloquial and the arcane when writing on himself. Thus, in his fascinating and demanding exercise in critical autobiography, Watching Death at Work: My Life in Film, he is capable of grabbing us by the lapels with such apt and cogent observations as this: “As I watched (Michael Snow’s Wavelength) flickering between boredom and fascination, it simply seemed to me the first film I’d ever sat before that required my attention.” Yet elsewhere he demonstrates a far less approachable critical humour. Here he is on 1989’s Eat: “Its archaeologies of superimposition are not an obfuscation of the present but its foundation, its history made manifest, re-invoked in a present which is pictured as an intersection of consumptions.” I guess when life at the margins is all you’ve got, in time it starts to feel like home.

It’s possible, at this moment – after such recent exercises in dramatic narrativity such as Kanada, Valentine’s Day and the forthcoming Blood Money – that Hoolboom is trying to move in from the margins, and this is at once both surprising and perfectly characteristic of him. This is a filmmaker whose primary aesthetic impulse is the exposure of the limits of discourse: how language circumscribes both identity and behavior, how images can be contextualized to “mean” just about anything, how narrative film practice represents the systematic elimination of what for Hoolboom is one of the most alluring properties of the photographic image in the first place: its infinite, unknowable ambiguity. Revealingly, in one of his first forays into scripted narrative, the little-seen but fascinating From Home, Hoolboom decides to make a fiction from a personal story of a relationship in decline, and then adopts the fictionalizing process as one of the film’s key concerns. “Why do we make stories out of such things in the first place?” From Home asks, while doing so itself. Then it answers, literally, “We make fiction out of them to make them universal.”

Narrative is a social contract, a way that otherwise incomprehensibly subjective experience is arranged according to certain widely shared laws of representation. For Hoolboom, the very act of narrativising is one of radical reduction: it’s the elimination of all other interpretive possibilities in favour of the one privileged by the storyteller. Its aim, like that of so much storytelling, is to control response and interpretation. Elsewhere in From Home, his unaffectedly confessional voice-over articulates an essential Hoolboomian epistemology, which itself is re-invoked in White Museum: “As a filmmaker or a viewer of a film, you always begin at the same place, with everything, with every image, and from there you have to make a selection, a choice.”

Each choice represents the blocking of yet another angle of interpretation. “What is being left out here?” Hoolboom asks us as we contemplate 1991’s Red Shift, and in 1981’s Now, Yours he wonders about the artificial credibility bestowed on something merely because it’s on film. “If you had anything to say,” he asks his audience, would you be on film?” In his early work, the infinite potential of response is something the films seem to promote. Not just in the way certain images recur from film to film, but in the way they’re recontextualized to take on new meaning. Later, as the films move – slowly, with guns drawn – towards dramatic narrative, they will only do so hyper-selfconsciously, talking to themselves all the time, like Popeye muttering his way toward another apocalyptic appointment with Brutus.

As to what’s characteristic about Hoolboom’s recent moves narrativeward, consider them the natural extension of his relentless self-consciousness: having moved far enough away from the paradigm of narrativity to see the machine at work, his artistic impulse has been overtaken by a desire to operate this machinery itself; to see how much improvising it will tolerate before he’s pushed back to the margins again. Plus, one sees in Hoolboom’s work, and in the breathtaking distance covered by the movement from the intensely subjective Self Portrait with Pipe and Bandaged Ear (1981) to the expansive sociopolitical concerns of Valentine’s Day (1994), an exhaustive, almost omnivorous cycle of hunger, ingestion and appetite.

Generally speaking, his practice is like a camera that slowly pulls focus to draw more and more into its frame. The early work reflects a kind of poetic subjectivity, as though the artist were drawn to non-narrative practice primarily because it seemed the only reasonable and honest means of representing subjective experience. From this, Hoolboom’s work develops a concern with the limits of its own articulation – with the relationship between form and expression – taking the terms of mediated communication as its subject. This concern reaches its most radical and memorable extreme with the almost masochistically confrontational White Museum (1986), in which Hoolboom questions, teases, cajoles and lectures his audience for over thirty minutes while we stare at the blank white screen of cinema degree zero. At one point his voice asks the projectionist to turn the house lights up so we can see who else is in the auditorium with us – or to find our way to the exits – then resumes a meditation on the audacity implied by the simple act of making personal statements for public consumption. “If I want to change the world,” he says at a point where many will already have slipped out the back, “I need to be visionary. If I want the world to change me, I need to learn to listen.” He is being typically modest: it is we who need to learn to listen, to discover in the white screen the possibility of our own capacity to hear stories and voices that are not contained within the frame of our experience. The white screen is either the butt-end of experimental practice or the threshold of infinite possibility. Or both.

Hoolboom’s recent longer works – which are as formally removed from the first-person minimalism of White Museum as radio is from painting – are nevertheless almost belligerently verbal, providing his actors with ripely non-naturalistic passages of discourse on art, history, politics, love and (most transgressively and exuberantly) sex. He seems to have struck some form of anxious truce with the words he once found so suspiciously arbitrary and inadequate. Now his characters spew forth ideas (“The body does not believe in progress,” says Callum Rennie in Frank’s Cock) and bon mots (“The worse things get, the better they look on television,” says Andrew Scorer as Prime Minister Wayne Gretzky in Kanada with a raging articulateness that recalls, of all things, a radicalized Oliver Stone. (I understand now why Hoolboom is such a Natural Born Killers fan: it’s like one of his movies with balls instead of brains.)

Gradually, all but the least intrusive visual devices are being stripped away. Frank’s Cock, which is essentially a one-person monologue presented on a screen split into four images, still demonstrates a lingering suspicion of the hegemony of words. Throughout, the monologue is forced to compete with the images – of microscopic cellular activity, of Madonna, of hardcore sex – that surround it. In Kanada, the dramatic sequences are optically filtered in such a way that compels attention to their form, and punctuated by scenes of an announcer (Hoolboom in a deathmask) reading news stories – to illustrate both how the drama we’re witnessing becomes media currency, and the absurd cost of that process. Stricken by senility some time in the not-distant-enough future, Prime Minister Jean Chretien declares his own penis the new unit of imperial measure. Valentine’s Day, which features two characters first introduced in Kanada, does so without the optical filtering, but preserves the masked newsreader (this time in a hockey mask). The script for Blood Money is the most seemingly straight ahead story so far: minimal use of formal self-reflexiveness, no cutaways to mock news reports. It’s enough to make you wonder if even Mike Hoolboom wants his place in the middle.

In the unlikely event that he does, it’s difficult to imagine him settling there for long. From the beginning, his practice has been defined by the search for the limits of expression; he’s like one of those aquarium fish who spend the entirety of a brief lifetime pushed against the glass. Besides, much in his biography suggests an almost congenital need to question, explore and expose. He has written of growing up beneath a dowry blanket of ignorance concerning his own family history and the amount of blood spilled along the pathway to that childhood comfort.

The son of a Dutch father – whose name literally translates as “hollow tree” (trees figure prominently as one of his most potently vulnerable symbols of self) – and a Dutch/Indonesian mother, Hoolboom has written harrowingly of his mother’s experience during the Japanese invasion of Indonesia, and her father’s incarceration. Years later, avoiding the draft, his father and mother came to Canada, where they had three children. Later, Mike, the oldest, would include in his work family movies of himself and his siblings, as a lever, prying the doors to memory. (Incidentally, these films were shot on the same super 8 camera (his father’s) that served the filmmaker when he began making his own movies.)

As a young man, Hoolboom ingested copious amounts of drug and drink, dabbled in performance art, and finally signed up for film school – in his words, to “wrap myself in the machine of memory.” From the outset his film practice was personal, relentless and anti-conventional, but the inevitable poverty and marginalization attendant to such activity merely seemed to compel to produce (he made 23 films in nine years). The longest film of his early years, the notorious White Museum, a 32-minute blank-screen-with-voice-over exercise, uses lack of cash as a way of discussing how money makes the reels go round: “I don’t have enough money for the images,” he explains to an audience left staring at a blank screen. Later, From Home (“the film damn near killed me to make”) was completed with $8300 of the filmmaker’s largely non-existent personal funds.

In 1988, when Hoolboom learned he had contracted HIV (“I didn’t really handle the news well,” he wrote subsequently with matter-of-fact understatement), it merely intensified his drive. Since, he has completed 27 films, organized experimental conferences and tours, started a film magazine and a library and written voluminous critical articles on experimental practice. Moreover, the revelation of the imminent deterioration of his own body has placed the artist squarely at the literal outer limits of existence, a place whose interest to him is therefore no longer theoretical or academic: it’s his home.

Which is why, if Mie Hoolboom seems to be demonstrating an interest in moving toward the mainstream, that move applies to the art but not the artist himself. While the form the work takes may embrace conventional elements, the issues it raises are anything but. Since he’s learned of his medical condition, Hoolboom’s work has expanded from the discourse of the body, language and cinema to a scathingly satirical examination of the institutions of state, culture and nationhood. For, as Escape in Canada (1993), Kanada, Valentine’s Day and the forthcoming Blood Money make clear, the artist’s own mortality has been consistently affected by the external machinery of social organization.

Thus, the language of state and nationhood is analogous to the discourse of body and self. Perhaps this is why Hoolboom’s Canada is a place stricken with disease, denial, bad blood and rampant ignorance of its own history: it’s the larger body we all share, and its limitations also mark the periphery of our own sense of who we are or imagine becoming. Like the cinema and memory itself, it’s a machine. The problem is that, as with the other machines he’s dismantled, Mike Hoolboom has already learned this one doesn’t work. How it’s supposed to work is no mystery: that’s what politicians and mainstream media are for. They draw attention away from the machine’s malfunction by emphasizing the exceptional nature of any such malfunction: a little tinkering here and there, and a smoothly-operating yet fundamentally unchanged system will be up and running again. To see how truly screwed-up things are takes someone who’s had a chance to watch the machine for a good long time. From a distance, and from the outside.

Program One: The Agony of Arousal

Justify My Love 5 minutes 1995

Red Shift 2 minutes 1991

Modern Times 4 minutes 1991

Mexico (with Steve Sanguedolce) 35 minutes 1992

Brand 6 minutes 1989

Shiteater 12 minutes 1993

Frank’s Cock 8 minutes 1993

Program Two: Theatres of the Self

Self Portrait with Pipe and Bandaged Ear 1.5 minutes 1981

Fat Film 4 minutes 1987

Now, Yours 10 minutes 1981

Install 8 minutes 1990

In the Cinema 1 minute 1992

White Museum 32 minutes 1986

One Plus One 3 minutes 1993

Scaling 5 minutes 1988

two 8 minutes 1990

Eat 7 minutes 1989

Program Three: Uh Oh Kanada

Shooting Blanks 3 minutes 1995

Escape in Canada 9 minutes 1993

Kanada 65 minutes 1993

Program One: The Agony of Arousal

Justify My Love 5 minutes 1995

As one of Madonna’s once-controversial music videos runs the gamut of high-gloss corporate erotica, a love letter of sorts runs across the bottom of the screen. Well, at least love of the kind a video like this might inspire. Of what “material” is the girl made, anyway?

Red Shift 2 minutes 1991

A film that worries about words: what they mean, how that meaning changes depending on who’s using them, how they work as images as opposed to text. Most pertinent question asked: “What is being left out here?” “The result is less an expression of readership than an insistent exposition of its image – as if words or their readers were only real to us insofar as they resembled an image.” (MH)

Modern Times 4 minutes 1991

Industry has rhythm. So does the hand-cranking of an old Bolex, and so too (in spades) does this punchy meditation on a body crushed by the wheels of industry. “I imagined the camera as a dark box admitting a slim and intermittent light into its dark interior and structured Modern Times the same way – framed by darkness on either end, miming the shape of its subject.” (MH)

Mexico (with Steve Sanguedolce) 35 minutes 1992

Travelling to Mexico, Hoolboom sees Toronto everywhere. History, landscape and art itself are viewed as elements swept up in the march of global economy, leaving our travellers to ask a logical but deeply problematic question: “Whose story is being told here?” One of Hoolboom’s best, and one that evocatively showcases his skills as a writer. “In the summer of 1989, Steve Sanguedolce and I drove down to Mexico with a carful of film gear. The plan was to shoot from the hip and we’d cobble the remnants together later. Which is more or less what happened.” (MH)

Brand 6 minutes 1989

Light plays on the surface of rippling water, while children frolic in a playground. The mood of this film is as elusive as memory. Everything is beautiful, everything fades. “Brand is a fugue of memory and the present day, a film lyric which crosses playground children with light playing over the water of Lake Ontario.” (MH)

Shiteater 12 minutes 1993

In nightmarishly high-contrast black-and-white, Andrew Wilson rises from bed and – often in extreme close up – geeks himself up in preparation for the pay-off of the title. Later, he ejaculates on the camera lens, creating a bizarre variation on the blankness of White Museum. As grotesque, repulsive and fascinating as it sounds.

Frank’s Cock 8 minutes 1993

In this, one of Hoolboom’s funniest, most heartfelt and irreverent films, Frank’s lover (Callum Rennie) rhapsodizes about the epiphanies in a life spent with his now AIDS-stricken boyfriend. Meanwhile Madonna, blood cells, and hardcore sex vie for our attention in the rest of the frame. Contains possibly the funniest reference to Peter Gzowski ever uttered in public.

Program Two: Theatres of the Self

Self Portrait with Pipe and Bandaged Ear 1.5 minutes 1981

Leader, emulsion blots and negative frames flash aggressively as a voice trills a single, piercing note. As a self-portrait, it seems beyond first aid. “All this points towards a last, lingering embrace, a parting kiss and dread that features here – in a soft-pedalled urban lyric humming the black and white of it all.” (MH)

Fat Film 4 minutes 1987

Grainy home movies of a distant childhood slam against restless images of contemporary domestic discord. Voices seem to emanate from past and present, contributing to an overall impression of film as collision with memory. “Fat Film is a blend of past and present, featuring the filmmaker as disinherited time traveller.” (MH)

Now, Yours 10 minutes 1981

Part of a trilogy, including The Big Show and White Museum, that takes the space of the theatre as its subject, this is a film that holds a mirror to our own responses. Among other discomfiting things, it asks: “If I asked to be alone, would you leave?” “It’s filled with a bristling paranoia, as if it resented the fact of its exhibition, a curious attribution for a film, to say the least.” (MH)

Install 8 minutes 1990

Art comes apart, to be reassembled at point of exhibition. Here Hoolboom’s artistic practice emphasizes the parts over the whole, as the film gradually installs itself in your senses. Contains the lovely and pertinent phrase, “sliding between light and shadow.”

In the Cinema 1 minute 1992

“I began to piece together a film where the title would be the lead player – the most important part of the film. I wrote out a statement on cards and filmed them one word at a time.” (MH)

White Museum 32 minutes 1986

No images. Just a white screen and Mike’s voice wondering what the hell we think we’re doing here. Funny, smart and occasionally infuriating. Cinema povera.

One Plus One 3 minutes 1993

A pixillated couple plays dress-up and undress-up as Earle Peach’s industrial-strength audio track pulsates and ebbs with churning tide of sound. Neighbours for the end of the millennium.

Scaling 5 minutes 1988

Observed naked by a laterally-tilted camera, one Mike paints a white wall black while another Mike paints a black wall white. A film that goes both ways. “A minimalist’s film noir.” (MH)

two (with Kika Thorne) 8 minutes 1990

Love in the midst of chaos and cacophony – or is it love as chaos and cacophony? “I’d been invited to a film festival in Germany and we trooped off together, super 8 camera in tow, squeezing moments of the everyday into the rectangular confines of the narrow gauge.” (MH)

Eat 7 minutes 1989

Food as the site of a host of cultural pathologies is the subject of this, one of Hoolboom’s most visually arresting and provocative films. Pornography, advertising, anorexia and apocalypse: superimposed and seemingly melting one into the other. “Eat is an attempt to begin not with the good old things but the bad new ones.” (MH)

Program Three: Uh Oh Kanada

Shooting Blanks 3 minutes 1995

A three minute reading by Mike Hoolboom. Tops.

Escape in Canada 9 minutes 1993

Having stumbled upon a hair-raisingly patronizing travel documentary promoting Canada (“the land of escape!”) as a vast playground for tourists, Hoolboom reprocesses it in its negative image. Which may be the only way a Canadian can position himself within such an alien projection of nation: from behind the screen that hides the truth of colonized national experience.

Kanada 65 minutes 1993

Inside, a hooker (Babz Chula) is reluctantly acclimatizing herself to co-habitation with her lover (Gabrielle Rose). Outside, Canada is negotiating with a big American network for the rights to televise its imminent civil war. In between, television news drones on in 24-hour perpetuity. Scabrous, funny and often brilliantly written, Hoolboom’s first foray into dramatic feature narrative is as promising as it is idiosyncratic. Sample line: “If voting made a difference they would make it illegal.”