To the Chalmers Jury:

I have known Aleesa for seven years. We met on the stairs of the Cumberland Theatre where she was standing with her friend Benny who introduced us. The screening (was it Miranda July? No. But it was something like that, precious and one-of-a-kind) was over and people were streaming by all around us. Our heads were filled with new pictures, as they have been ever since. And in the subsequent years we have met most often at Charles Street Video, a place where the flow of pictures old and new can be managed and ordered and named. No surprise at all that she works there now as the in-house editor.

Aleesa’s work is related to ‘received wisdoms,’ it is largely made of footage made by others, and from this archive she extracts, with an uncanny precision, particular moments. While the role of the found footage artist is hardly a new one (even TV promos feature clip montages culled from the vaults) this is so very different. Aleesa gathers so that she can change the speed of her materials, she lets them settle inside her, until they become her pictures. These images wouldn’t “belong” to her any more than if she had gone out and shot them herself. Somehow, her role as an artist involves the recasting of these pictures into moments of her own life. These small instants, grown back inside the body, then become a new alphabet which she uses to write new stories, which belong entirely to her. And then to all of us.

Over and over again she returns to the middle class home where actions which never happened for the first time recur again and again. This sutured medley, broken and reassembled to show where the cracks are, make evident something of the strain of having to live inside these houses. She shows us the pictures we live inside. She arms herself with her feeling, and then she moves out into the world where everything is a bit too much and overly sensitive, and from these difficulties a politic arrives.

She raised the bar for her practice with a pair of movies made in tandem, worked on (and over and accompanied, lived in and lived through) over the course of some formative years, when she was in search of a container for a particular progression of emotive possibilities, of re-drawn narrative tangents which would at last become her narrative, her sense of enclosure and entrapment and escape. This pair of twins (they are fraternal, they don’t look alike) she named Supposed To and Ready to Cope. They were finished in 2006. She used the same strategies to produce her next work, the multi-screen installation piece Something Better. Here the gender divide looms large, and she is prepared to individuate her subjects, not only floating them into a cascade of pictures but holding them up and allowing them to speak. She gives us permission to attach ourselves to them, before she firmly and gently releases them. This sense of immanent departure marks all of her work. The way the pictures enter, the way the pictures leave, they are like cabaret acts under a kindly stern ring master. This makes for a satisfying surface, it’s so easy to be swept up in all that gloss which is necessary to hold the pain which lies everywhere under the surface, almost and always about to break out. Smothered in all those honey dripping Hollywoodisms, the smooth electro-beats, the finger popping montage, it’s only then that the real pain can be entered and admitted and lived again.

Something Better is a summing up and denouement of what has gone before. Now she is prepared to go further, and I am holding my breath in hope. The stakes are high, the pictures already overcoded, the machines are waiting. She is ready. After everything that’s happened, there are new stories only she can tell. Let her have the voice to tell it. Give her the blade, the flatscreen, the body of pictures. Let the cutting begin.

Twice Told Tales: an interview with Aleesa Cohene

MH: Has every experience already been photographed? Is that why you use found footage?

AC: Every experience and emotion cannot possibly be photographed, that’s why I use found footage. The realms of experience and emotion are infinite, yet so many of us choose familiarity and stability over risk and the unknown. I’m fascinated by how much silence and suffocation there is in each human interaction.

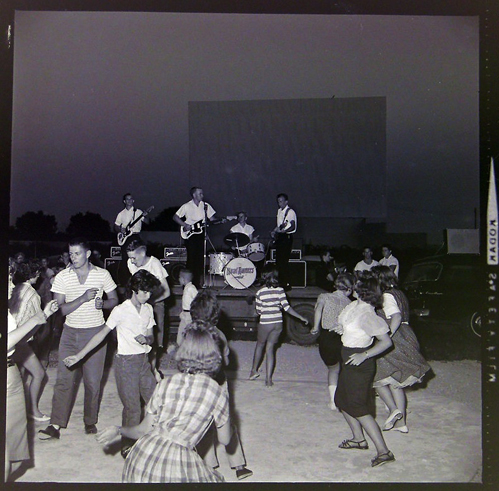

We watch movies to feel something more than we allow ourselves to feel in our everyday lives. Recorded images and sounds double as mirrored echoes where we don’t have to look or listen to ourselves, we only have to be quiet and watch the screen. I think this is an everlasting power of cinema. It permits us to be who we want to be free from responsibility and action. It releases us from guilt and shame. The more I pick through old movies the more I find a history of this psychological etiquette. My work aspires to understand why we live in a poverty of emotion and how it can change.

MH: So you feel that becoming like the pictures which surround us could make us more human? What a lovely idea. But don’t movies also render us helpless and infantile? It’s not my fault, it’s not my problem—movie going equals actions without consequences and what could be more dangerous than that? Many sociologists, certainly censor boards and the governments they represent, are quick to point to the negative impact of movie going. Do you feel that its outpouring of feelings outweighs these disadvantages?

AC: It’s both these forces that attract me to using found footage. The tears that stream down my face when I watch A Birth Story coupled with the difficulties I have with so many aspects of parenting, is a familiar disjunct of our technological times. Without the tears, despondency reigns, and I think that if anyone is going to change something they believe is wrong, they have to know how they feel about it first. We live in a society that mistakes cohesiveness for political action and sameness for power. Most movies (at their ideological core) perpetuate this. But I think the emotion we take away from movies overrides their plots. Perhaps that’s why stories don’t change and people do.

MH: Some would argue that you are doing nothing creatively, you’re not adding anything new, only parasitically taking what others have done and reshuffling them before signing the results. How would you respond to these criticisms?

AC: I would argue that everything is made by reshuffling. New buildings are based on parts of existing buildings. Medicine is based on new combinations of chemicals. Nothing is without multiple origins. Origins can be hidden or exposed and I’m not interested in hiding what I edit. My creative tool is editing and without footage my art is not visible.

MH: Can you describe your process of collecting pictures? Do you have a source archive from which your pictures are drawn, or are you continually on the hunt, looking out for another, better shot?

AC: I have an archive of shots that I’ve been collecting for the past five years. I’m also always on the hunt. I try to stay ahead of a desperate hunt though, which always involves a shot that is too specific. I’ve decided that these shots don’t exist, I only want them to. Instead, I have a system of collecting things in groups; people walking down hallways, climbing stairs, driving cars, sleeping, on the phone, taking a bath, running away, opening and closing doors and windows. Once I’ve grouped clips into thematic categories, I make sub groups of emotional categories. I find sound harder to divide this specifically so I organize it differently, such as: ambience and texture, sound effects, ethical assertions, emotional expressions, excuses, admittances, beliefs and anyone discussing truth. With each idea I focus on there are always other categories I create for the footage I find. Generally, though, I’m looking for moments before and after an event. Whether it’s anxiousness, anticipation, denial, or relief, the emotions that frame actions are points of relation, they might be mine or yours.

MH: Are there some shots that are so powerful, so moving, that you want to make a movie simply so this moment can be felt in the way you feel it?

AC: Yes. These are also the shots I can’t put into a category other than “favorites.” They are moments that are layered with complex and multiple emotions. I often use them to structure a video. The first shot in Ready to Cope of the boy picking leaves off the bush is an example. He seems so sad and at the same time paralyzed by his sadness. In the original movie, he had just killed his brother when they were out hunting. His shock and grief is buried by guilt which is what I believe national security is based on. That’s why I chose it to open Ready to Cope.

MH: You spent a good while cutting Ready to Cope (7 minutes 2006), why so long? Were you looking for a new relation to your pictures, trying to get them to “make sense” in a different way?

AC: Beginning in August 2005, I scheduled one day each week to edit Ready to Cope and Supposed To. However, I’ve found it impossible in my work life as an editor to predict the length of a project. The work that I was doing for money often bleeds into time for my own videos. Juggling this aside, I also encountered many other challenges with these pieces. My first intention was to concentrate on our cultural obsession with uniformity and homogeneity. Once I felt I had collected enough images and sounds and began a paper edit, I discovered that the underlying fear of these themes were far more interesting and pervasive especially with recent political debate regarding safety and security in Canada. It’s clear to me that my own desire for order is very much grounded in a fear of chaos. Chaos breeds strictness and strictness privileges sameness. The same cycle exists in the hundreds of horror movies I went through; something disrupts or invades a clean house, a good relationship, a sweet family, a good intention. A desire for goodness is destined for disturbance. This then became my focus. How do we define goodness? How do we protect ourselves from impending doom? These difficult questions took a long time to build a narrative around, especially since many of their qualities are repressed and nuanced.

MH: Is it necessary to arrive at new forms and new relationships in your own life before being able to apply them in your movies?

AC: Yes. For the past seven years my work has been based on the questions: What do I believe? And what am I afraid of that makes me believe that? The answers to both questions always have something to do with the ideas I trust and the relationships I have.

Lately I’ve experienced a rawness that is very new to me. I easily lose a sense of myself. I’m overwhelmed by anxiety and hesitation. I guess I feel like I’m fighting a lot of skepticism. I trust less people than I used to. I remember feeling something important going on inside me and sharing it with several people, looking for different perspectives and reactions. Now I barely want to talk about important personal things, as though they will change if they get out, as though I’ll lose something. The examples I can think of are small and wouldn’t make much sense to anyone else.

The person who is closest to me right now is Tema, and she hates the word integrity. She understands it as a grandiose idea about Truth and Properness, something no one can live up to even though everyone tries. It’s an archetypal vision of “rightness.” A choice you make one day may seem full of integrity while another choice might negate that integrity. This contradiction is how we are human. The idea of integrity is a static unflinching notion but to be human is not. She says that the only beings that have integrity are animals. Her distaste exposes the conflict in ways that aren’t possible on my own. We argue about it all the time; I feel the conflict is primarily within oneself, a grappling with an inner knowledge of right and wrong. She tries to determine what is most compassionate outside of her personal desires. She spends a lot of time with animals.

When I was first being politicized in my early twenties, feminism and anti-oppression politics taught me to be an ally, to speak from my experience and to hear other people’s opinions as their experience and to understand my privilege. It was my responsibility to identify my own prejudices and actions which perpetuate oppression. Dialogue and discussion are necessary to learn how to listen non-defensively and communicate respectfully if an anti-oppression practice is going to be successful. I realize now how deeply skeptical I am and how far apart experiences are from how they get told; how “owning” an experience invites comparisonism and often competition, and how often self reflection deepens oblivion. In moments I think I’m being straightforward, people seem confused. I’ve always thought of myself as overly sensitive but often get told I’m not sensitive enough. In the darkest part of this reality, tragedies are compared and compassion is measured accordingly. It feels as though theory and practice are colliding with one another, cancelling each other out. An insidious system of erasure resides at the base of the ideas I trust most. I see it in the world, in myself and in others.

I remember a few days after the second levy broke in New Orleans I was at a bar with friends. People were discussing connections they had to people effected by the tragedy. One person talked about a woman she knows who was getting ready to leave New Orleans to go to school in San Francisco. She made it to San Francisco having lost all her possessions. She only had the clothes she was wearing and the items in the bag she was carrying. The person telling the story explained that she came from a fucked up home, “Her mother collects Barbie Dolls,” she said. I got angry with her and asked why that meant her home was necessarily fucked up. The conversation died prematurely (as most conflicts do) but I still think about it. What bothers me most is that a sad situation cannot simply be sad, it needs to be punctuated by morality in the form of what I believe was understood in this case as feminism. Whether or not this woman’s mother’s Barbie collection was a source of abuse, neurosis, a hobby or art, it cannot define wrongness by itself. Nothing can. Like an anti-oppression framework, feminism is deeply committed to ideas about not generalizing feelings, thoughts or behaviors, and is therefore devoted to reconstructing and redefining power. Yet, I’m not sure most feminists or anti-oppression activists are personally committed to the same things. We want to tell a good story, to make people laugh, to be loved. We want things to set us apart and make us feel special. The woman telling the story wanted to hold an audience. For many reasons there’s shame in these desires, causing us to hide and to value opinions over feelings. I know I’ve said many things just like the woman who told this story. Perhaps the reason it stayed with me is because it reminded me of ways I don’t like myself.

MH: Ready to Cope begins with a voice-over which asks, “In the history of Canada has there been a crisis this deep, this merciless?” Where did you find this quotation and what drew you to it?

AC: I found this piece of audio in a documentary about farmer’s rights in Canada from the early 80’s. It was one of the first things I knew I needed to use. The woman speaking is passionate and honest. I was especially drawn to the idea of a “merciless” crisis providing a shell for the cyclic relationship between self protection, denial and national security issues. I’m interested in how drawn we are to wanting and needing mercy, when we often can’t give ourselves a break.

I also knew that I wanted to establish the ideas in Ready to Cope within a frame. When something is named a crisis, there is often more tolerance for emotion, hysteria, speed (or immediacy) and even a kind of abstractness that is not acceptable in a “professional” environment. Ready to Cope contains all of these elements so announcing a crisis set an appropriate stage.

MH: Your movie is framed by people taking the next step, in high heels and sneakers, inside and out. The effort of going on, of getting up over a paralyzing sense of malaise and anxiety, is everywhere palpable. Much of this dread is centered in homes where doors are ominously approached and hallways are the circulation system of unseen fears. Why have you placed the middle (class) home at the epicenter of these fears?

AC: “The middle home” is an interesting way to look at it. For me, the home is where most of our unconscious fears are rooted and where we act through and against them. In a lot of my work it functions as a figurative source for the themes I address. As a child, it was in my own home where I first learnt to manipulate, to dwell in insecurities, and mostly to feel the depths of hopelessness and despair. I grew up feeling affected by everything; stuffed animals that had a bad look in their eyes, wallpaper patterns that moved at night, babysitters I hated the smell of, and fantasies of running away so I could be a different person. I would put on a dress that I hated, pack a bag and walk out the front door. I remember thinking that if I wore an ugly dress people would treat me differently and I could begin a new life. Nothing felt right though nothing was ever all that wrong.

But “the middle home” is a place that is similarly represented by most movies. Unlike my own obscure memories of growing up, the collective home functions as a receptor for collective fears that we can attach to our personal experiences. A creepy shadow in the hallway reminds me of the shifting cloud patterns on the wallpaper in my childhood room. Only now I have an enemy. This same shadow reminds you of an early fear of yours, and in an instant we have a shared enemy.

When I was developing ideas about safety and security for Ready to Cope I knew I had to disassemble why movies can scare us so profoundly. The connections to our early understandings of fear have no explanations for many of us, and illuminates why similar narratives can scare us infinitely. Movies provide us with pictures that we’ve been waiting to put content into and explanations we crave. Conscious or not, the fear we feel when watching movies must be a continuation of where it all began, but often stripped of its original uniqueness and sometimes capable of providing false and easy answers.

In Ready to Cope I wanted to bring the obscurity of early experiences of fear back into a collective dread and anxiety. What if the creepy shadow is my own? What if I forgot to lock the door and the wind blew it open? I focused on the home in order to ask questions like these and to bring focus to our only true collective enemy: ourselves.

MH: The home shrinks and bursts open until a body falls from the sky, lies on the grass, runs into woods. When images of home return they are seized with a new pressure and violence, they build until they break in a shattering storm of broken windows and dishes. You close the movie with a trio of shots: a woman puts it all away in her cupboards, a girl bends down, a sneaker leaves the room. It is a powerful ending, especially because the movie stops here. Why these three shots, why are you filled with so much hope?

AC: At the end of Ready to Cope a woman is searching through all her cupboards. Looking for something but unable to find it. In the next shot a girl creeps down, and peers under a stall, knowing that something or someone is there. And yes, a man’s sneakers leave (or enter) a room, and the movie ends. I never thought of this ending as hopeful but I suppose it is. I edited the video to reflect the idea that the fear we feel is a fear of ourselves. So I structured the last thirty seconds (three shots) of the video as a reprise of my thesis. The reprise begins with a frantic search (shot #1); a feeling of having lost or misplaced something can feel like you’ve lost a part of yourself. Then, from within (shot#2), you gather some courage and look one last time. Maybe it’s the last place it could possibly be, maybe you hear a strange noise and know it’s there. In the final shot, action is required, you must choose to enter or exit. I know that my translation of these images might not be communicated to the audience the same way I’ve explained it here. But like all my work I hope it’s experienced in flux; as we experience things emotionally. Maybe this is why you feel like I’m hopeful. I think hope is only possible when you know things will change and that you can participate in the change.

MH: The pictures your movies are drawn from are from other people’s movies, from a “public record,” so I’m wondering what your relation to your audience is. Once upon a time you were “equal,” both spectators in a theatre, or video store patrons. But now you have taken portions of this shared understanding, this visible inheritance, and turned it to your own ends. Are you attempting to activate a new kind of spectatorship? Who are your movies for (only the usual suspects: those who attend art video fests for instance)?

AC: I’m of two minds. On one hand, my relationship to my audience is strange. There is so little dialogue about video art (about so many things) and my work speaks to this. So I’m often confused by my audience. Who they are, who I want them to be, what they think, what I hope they think. This confused silence of mine and theirs feeds new ideas for new projects so it’s sometimes hard to imagine anything different, any “new kind of spectatorship.”

On the other hand, I have a lot of fantasies about who my movies are for and where they could show. I feel like they are trailers for our problems. I think about what it would take to offer art as a public service. I imagine an advertisement:

Feeling anxious?

So are we.

Watch this movie…

If you feel worse, that’s good.

If you feel better, that’s good.

My divided perspective is probably why I make work in isolation, but most days I work as an editor with various community groups and other artists to produce videos they want to make. I haven’t found a balance and I’m not sure if there is one.

MH: Supposed To (7 minutes 2006) has a feeling of barely controlled rage which is smoothed over by its sweet pop electronica and your assured montage. But I’m wondering if you could talk about the origin of this visceral anger-the movie feels like it wants to reach out of the monitor and choke me. Like your other work, this movie is made up of pictures made by others, why is it important to refract your feelings through others? Are you using found footage the way others would deploy actors and scripts?

AC: When I first started thinking about and using found footage I was also reading a lot about psychoanalytic theories of projection. The idea that we attribute to others our undesirable thoughts and emotions became key for many personal and political questions. Found footage is the cultural source of an ingrained defense mechanism.

Undesirable characteristics are not only being displaced onto other people but also onto animals, inanimate objects and social constructs. We create scapegoats in order to feel better. When I feel frustrated about something in my life I’ll often hate the way a piece of furniture looks. I’ll move it around the room hoping to like it better at a different angle, in a different spot. Editing of all sorts has become the manifestation of many of my feelings (anger included). Any time I dig for the root cause of a feeling, possibilities and combinations multiply. Nothing feels like it exists without its past and future relationships. The origins of my anger exist equally in my past and in movies I haven’t seen yet.

MH: Because you work with status quo pictures are you concerned that the many people who are never represented in movies (the working poor, immigrants, the elderly…) are similarly missing from your work? Does your work mimic the exclusions of mainstream media?

AC: The images I choose are steeped in representational stereotypes. And the presentation of the work (as you’ve indicated) is exclusive and limited (video festivals and galleries). These realities weigh on me and at the same time push me to keep working.

I’m always interested in what type of person is cast to play different emotions. There are so many hidden rules. When a horror movie deals with an “unknown phenomenon,” the main character is usually a white woman with straight brown hair. If her hair is curly, then perhaps she’s called the evil to her, and if she isn’t white, well then she is the phenomenon itself. The racist, classist, sexist realities of these movies have been analyzed by many people and it’s my hope to continue the discussion using the pictures themselves.

MH: A young girl looks into a mirror, but when we see the answering shot it is a man’s face that looks back at her. Throughout this movie you disperse subjectivity between genders and across different age groups. You ask us to unify these experiences, these bodies. I understood the climactic scene where a man crashes through a window as emblematic of this broken subjectivity. As a viewer my identification is asked to shuttle between the two poles of broken and whole.

Supposed To is carefully structured, filled with rhyming gestures (a hand wipes the windshield of a car, other hands grip a steering wheel, a third shot shows yet another car on the road, though the montage makes it feel as if it’s all the same car). Can you talk about the overall structure of Supposed To with its prelude of first steps, its attempted escape, the window crash, the telephone call and the return home.

AC: Like all my videos, Supposed To is structured through intuition. I’ll write scripts prior to editing; or elaborate paper edits to structure the argument I want to make, but it always changes during editing. Each shot has its own rhythm and each edit its own meter, so no matter what I want to say conceptually, I’m led primarily by mood. The montage produces a sequence of emotions; the struggle is for the emotions to say what I mean.

Supposed To begins with a scene of a boy helping an old man take off his boots. The old man pushes the boy’s bum with his foot to help him get the boot off. The scene is simultaneously sweet and creepy and acts as a prelude for an investigation about obligation and guilt. Following this is a series of feet taking steps through a field, up stairs, in hallways, outside a door. It is a collective arrival by people who, at least in my mind, have come to hear: “There’s a whole machine that works because everyone does what they are supposed to. I found out I was supposed to be something I didn’t like.” From here the movie begins unraveling the complexity of work; a suitcase falls, a woman scrambles through her wallet and sees that her ID is gone, another woman falls into a pool, a man in a uniform collapses, shots of losing oneself are interwoven with people at work. A man sits at a table eating bananas in milk as another voice talks about working nine to five and how that “snuffs out eccentricities” and results in passive aggression. A woman vacuums. A girl looks into a mirror and sees someone else. This continues from person to person, each facing themselves in order to see another. People are shocked, confused and frustrated.

This catalyzes a change and escape. A woman puts on her housecoat and another woman looks out the window. A young woman frantically gets into a van, people are packing, and a series of cars driving occurs. A boy sitting in a vehicle turns his head and says “Know what I did?” A shot of scattered clothes and broken glass follows. A woman is on the phone, she covers the receiver and says: “He broke a window.” The escape has prompted a confession about something that hasn’t happened, or at least doesn’t seem wrong. The confession itself has caused a crime. A series of people fall through windows, and glass is scattered on various floors. A boy is running away. A man lies face down on the shore.

The final scene begins with the phone ringing. A woman picks it up and hears a man’s voice saying: “Time has come to put aside childish things…” Three more women are listening on the phone and one says “OK” in response. The man continues “Face up to who you are…” Three more woman listen. The man says “…suspicions of destiny…”, “…surely you must be feeling it…” A woman answers, “Yes, I am.” The voice continues, “We all have them…” and a boy on the phone answers, “Oh, OK.” The man concludes: “…a deep, wordless knowledge.” A woman looking in shock hangs up the phone followed by a series of hang-ups and a boy saying, “Did I do anything wrong?” Shots of a few people located outside houses appear and a woman says, “I thought it was all over.” A woman enters a room and takes off her stockings, another woman drops her keys and the final woman drops her coat, returns to a bed, sits down, hesitates to pick up the phone and instead sits in silence and bows her head.

I hope the end explains itself. For me, the scene is very dramatic and enters a new territory. Something I will develop more in new projects.

MH: All Right is a very unusual hybrid film: part found footage collage, part immigration polemic. Can you talk about you became involved with issues of displacement, borders and Canadian immigration? Why did you mix these concerns with found footage, how does the ‘other’ footage function in the movie?

AC: The ideas in All Right are based on experiences I had doing various types of activist work around new immigration policies and detainee issues after 9/11. I learned about a Toronto Immigrant Holding Centre which is a converted motel near the airport where refugees and immigrants were being held for long periods of time in poor conditions, behind razor wire, without information about why they were there. This detention centre was called the Celebrity Inn and is now called the Heritage Inn. It is a large place where people (mostly women and children) are brought directly from the airport. Reena, my ex-girlfriend, worked with a group that made visits to the centre, played cards with some of the people and worked to get them the aid and information they needed. All Right grew out of the reality that refugees and immigrants can be arrested or detained without criminal charges and held indefinitely once they arrive in Canada until they are granted citizenship.

Once I started researching immigration issues in government sponsored footage I realized that we have been talking about the same issues in Canada for years. Many of the documentaries I searched through were made in the early 80s and still felt relevant in 2004. I believe that there is an unstated kind of racism in Canada.

When I was in high school there were a lot of Asian immigrants from Hong Kong in my classes. They had been sent to Vancouver without their parents, many had houses and cars, that’s where the parties were. My mother said the reason mothers didn’t accompany their children is because they were afraid that their husbands would be unfaithful. She had no Asian friends, there was no way for her to know anything about the lives of these people, but this story made her feel more comfortable with them being “everywhere.” Many referred to the new immigrants as the “Asian invasion.” People said it freely without any shame, without any reference to their own immigrant history. When I was growing up, racism was never called racism, it was simply entitlement and maybe very complex fear. When I started thinking about the characteristics of this shameless racism, many images came to mind. I began looking for movie moments where people are confused, unable to see anything around them. There’s a shot in All Right showing a guy from his thighs down, he’s on a gravel road and kicks a rock. It’s so defeatist, it feels like a powerless, childish gesture. There’s a woman wearing a dress searching through a grassy field. The drama of her action foreshadows the fact that she’s not going to find whatever she’s looking for. A woman turns a corner and runs down a hallway; without seeing who is chasing her or what she’s running from she can only be running from herself.

The movie opens with a boy bending down to kiss something, a creepy woman’s voice says, “Feel it, it makes you strong.” Her voice provides an emotional anthem for the piece, an emotional calling for the nationalism which the movie takes up later. A woman turns to a man in a car and asks him if he feels it and he responds, “I feel things as they come, come on.” This concludes the anthem. He opens a door, another man walks through a door into a bedroom suspicious of something being under the covers. He tears off the covers and nothing is there. What stops people from feeling things as they come are suspicions. Then the song begins and the title comes up. We work to make things seem all right, but they never are because we’re not present to how we really feel. These fears are also felt on a nation wide level.

I took footage from a Canadian documentary called Who Gets In? and officer training movies from Immigration Canada. In one sequence we watch an interaction between an immigration officer and a woman who is applying to immigrate through the lens of emotional manipulation. They have this exchange.

“Because you want to upgrade? Because you want to study computers? Well I’ll tell you honestly, very honestly, I don’t believe you.”

“Sir but…”

“That’s what I think. The new employment that you want to find in Canada I don’t know what you’re going to find in Canada. I’m meaning that I’m not sure that you know what you’re going to find in Canada. Because you know nothing about Canada. I would not invest anything if I were you. You will not be going to Canada.”

What he uses to make a decision about her application is based on a judgment on what she knows or doesn’t know about a country she’s never been to. It’s manipulative criteria. They’re not having a conversation, he’s telling her what he believes, and what she thinks. Based on his judgment of her he’s decided that she’s not eligible. When a real dialogue doesn’t take place interaction is reduced to superficial impressions and racisms. Scenes like this helped explain to me why no one knows and even fewer care that a motel has been turned into a covert detention centre.

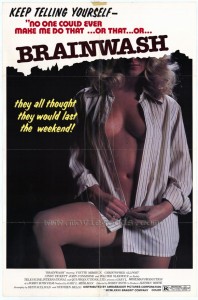

MH: There is a striking shot where a blonde woman comforts a large naked man. Can you talk about the origin of this scene and why you included it in your movie?

AC: This shot comes from one of my favorite movies, it’s called Brainwash. It’s about a woman (the blonde) who takes over a company using psychological tactics that break people down to their rawest emotional selves. The naked fat man is Buddy, who she asks to strip in front of a group of men and talks him through his childhood sexual abuse as the explanation for his weight. I keep thinking I’ll use the whole scene, but tend to grab tiny bits from it for various projects. She manipulates the employees of the company under the guise of compassion and moral integrity. The shot that I use in All Right occurs at the end of the scene. Buddy exposes himself, physically and emotionally, as she encourages him to cry. He does and she hugs him. What stands out for me is the complication behind compassion and care. At the time, this scene felt a lot like what gets called “standard procedure” by the Canadian Immigration Department when it is really the excuse for arbitrary treatments.

MH: Your new movies have just premiered at the Impakt Festival in the Netherlands. How was it?

AC: Supposed To was a part of a program called “Survival of the Fittest,” which carried this description: “The rat race of modern life makes ever greater demands on its participants. For the moment, there is no room for compassion with the less talented. What does stress do to people, how far can you go in your ambitions, and what will the future of our industrial society look like?”

The Central Museum’s auditorium is a black glass box that makes day feel like night. When you’re inside the building you can see the outside darkened through the tinted glass, but when you’re outside you can’t see in. Supposed To screened second in the program. Following the first voice of an old man saying “Help me out with these boots would ya?” there was a loud noise. I thought something screwed up with a speaker, but when I looked over I saw a guy on the outside of the building with a hose spraying the side windows. The projectionist went over and banged his fist on the glass. The man didn’t hear the banging and continued washing the window until the projectionist went outside to tell him to stop. The entire interaction was visible from inside the theatre and functioned as a replacement scene for the first three minutes of the video.

When the screening was over, I took a train back to Amsterdam and thought about what had happened. In many ways, it was a perfect live scene for the movie. I’ve often wondered how I might want to integrate live components into my work. Maybe this is a beginning. Two men were trying to do their jobs and one conflicted with the other. Both men were angry and the audience was watching. I was embarrassed. I was embarrassed for the window washer who was not only told to stop doing his job but was being watched by everyone inside without knowing. I was embarrassed for the projectionist who tried to tell the window washer to stop and in doing so became just as much a spectacle as the disruptive window washing. And I was really embarrassed for myself, as though I had planned the whole thing.

Videos

Absolutely 8:24 minutes 2001

Abscess 10:18 minutes 2001

Alter 20 minutes loop (installation) 2003

All Right 7 minutes 2003

Supposed To 7 minutes 2006

Ready to Cope 7 minutes 2006