An interview with Ken Jacobs

This (written) interview with Jacobs was conducted by Eduardo Thomas, curator of the fringe portion of Mexico’s nomadic Ambulante Festival.

ET: What is the role of documentary films within the contemporary context?

KJ: People struggle to document historical reality often at great personal risk, I respect them enormously, but let’s not expect Americans to respond in numbers that will effect much of anything. Maybe in other cultures, but this one is so blitzed by commercials, by professional liars—entertainers we call them—that the most revealing film will be judged above all on its entertainment value. If it gets shown; if one can find it. You recall Pinocchio’s Pleasure Island? That’s where we are. Our politics are movies, personal relations are movies. Watch us, listen to us playing ourselves, alloys of roles impressed upon us. And do you think characters in movies can respond to facts? George W. Bush imitates John Wayne who safely played heroes on a Hollywood set, dangling a masculinity before audiences as contrived as the breathless femininity of Marilyn Monroe. Ronald Reagan strove to confuse his trivial movie-persona with that of Gary Cooper, the people’s favorite Judas-goat, and made his Presidency a full-time starring role. America is bullshit aka a movie and its people are lost in fictions. Documentaries bounce off heads caught between porno and Jesus. Criminally ignorant, criminally stupid? Tempting to think so but let’s acknowledge their conditioning. The monied powers have worked at them for many generations; they didn’t become this benumbed overnight. They’ve been methodically deformed.

ET: In your opinion, what is the border between documentaries and experimental documentaries?

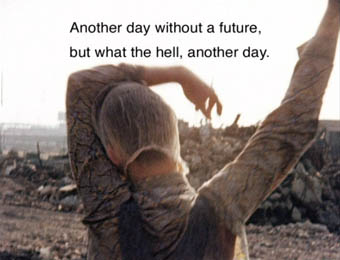

KJ: I deplore documentaries that speak to power in hackneyed ways. That toe-the-line esthetically hoping the message will then appear reasonable. We need more hopelessness to clear away these terrible self-sacrifices, more spitting in the eye by filmmakers, more absolute self-expression and let the viewer meet the work like any challenge in life. If s/he opts instead to stick to a diet of witless entertainment, no loss! Or the loss probably took place before adolescence and connection was never meant to be. I want art—documenting interior or exterior—to come forth unbridled, vehement, vivid.

ET: Why do you use found footage and archive material in your work? What is the value of these materials for you?

KJ: I am putting myself and my society on the couch. These are the deeply informing personal dreams that we recall by playing them again onscreen. Now that we can recognize the lies that passed into our deepest selves when we were unguarded—now that their styles have become comically dated— perhaps we can now prepare ourselves to fend off up-to-date lying-styles. Well, I can dream, can’t I?

ET: How could a more indeterminate experience in film be achieved?

KJ: Indeterminacy follows from non-manipulative utterance. When no-one tries to size-us-up and work us over just-so but directly comes out with what they have to say, however it seems best to lay it out, then we’re free to respond as individual persons and not as mechanisms.