- Kika Thorne: What is to be Done? (an interview) (2001)

- Bodies and Desire: The films of Kika Thorne (2000)

Kika Thorne: What is to be Done? (an interview) (2001)

The work of Kika Thorne follows a trajectory from the private sphere to the public. Each of her films carries a diary address and arises from personal encounters, or as Kika describes it, “just hanging out.” These casual, low-tech documents of the underclass come armed with a barbed politic, whether the sexy feminism of her early work or the address to urban homelessness in her more recent efforts. While she has used a variety of low-fidelity methods, super-8 has been her most reliable companion, providing both portability and an accessibility of means. Whenever the need arises, the camera can be passed on to participants for their point of view, and its no-budget results serve as example to any hoping to commit their own dreams to emulsion. A thoughtful intimacy passes through these desiring machines as they demonstrate new kinds of pleasure, even as the unyielding pressures of capital seek to reshape the body politic, threatening the usefulness, even the existence, of fringe media.

MH: How shall we start?

KT: Women’s voices are high-pitched so they can travel further to protect women from rape.

MH: Go on.

KT: The male and female voice are two different pictures, separated by pitch and vocal range. Often men can’t hear women’s voices at all. Sometimes women can’t hear men because men are outside the range of relevance. I’d like to talk about the scream at the end of the Toronto Video Activists’ Collective tape. Cops have chased down a homeless man and are busy laying a beating on him. The cameraperson finds them by accident; she’s already seen too much, she wants to go home. And then, there they are in front of her, and she screams. That scream signals a level of concern not yet present in the viewer. It underlines the difference between how she witnesses and how we watch her bear witness. When you, as a viewer, recognize someone’s real concern, it accelerates you into their space. In a very short time you move from voyeurism to engagement.

MH: Is that acceleration what you would call politics?

KT: It’s engaged attention.

MH: If you engage your attention with a film showing dust falling off a wall for an hour, is that political, too?

KT: That’s mind-numbing.

MH: Most imagine fringe film as a wall of dust.

KT: Most think of experimental film as confessionals with flickering difficulties attached. Dust falling from a wall is an art piece. It approaches sculpture. Meditation. Experimental film is more theatrical. So far as its politics go, all art is political. Some work is regressive, complicit with a neo-colonialist status quo. That’s not to say that delicate forms of attention are inherently capitalist, not at all. The shift of attention those difficult works require opposes capitalism.

MH: Maybe attention could be thought of as a set of grappling hooks. The attention that being a consumer, or watching television, requires allows those hooks to become deeply embedded. Sometimes difficult work can slowly lift these hooks from their moorings and send their viewer somewhere else.

KT: A lot of fringe work is made alone, celebrating the solitude of an eccentric and hyper-individuated subjectivity. Unfortunately, this is exactly the state that capital would have us in.

MH: Let’s talk about your latest vid.

KT: The Up and the down (5.5 min video 2001) is a didactic diptych about the Left and the Right. The left-hand screen shows footage from Fighting to Win by the Toronto Video Activists’ Collective. It’s a document of the June 15, 2000, riot at the Ontario Legislature in Toronto. The Ontario Coalition Against Poverty organized the event to protest the deaths of 22 homeless people, the loss of rent control and changes to the welfare system. The image starts with the protesters trying to get into the Legislature. They’re met by riot police, who drive them off the public grounds and across the street. The cop violence worsens. You see six cops zeroing in on one protestor, beating her into the ground. The audio of the riot begins in silence and grows louder as the violence becomes more personal. When the images are at their most newsworthy you can’t hear the sound, but as they become more subjective the sound asserts itself. The right screen depicts a young, ambiguous, but potentially right-wing class. Two girls and a boy. They’re just hanging out, playing and talking. Because of their dress and hair, they seem to be part of a counter-culture. Could these be cleaned-up images of the protesters on the other side of the screen? Or will these kids grow up to be website designers for the Royal Bank? There’s no emotional centre in their interaction, because I incorrectly depict the Right as alienated. Meanwhile, the Left is still captivated by the energy of revolution; it can’t let go of this romantic, violent vision of a society’s transformation. The Right is insidious, collecting the culture of cool that comes out of the Left and transforming it into capital and allure. I wanted to create an experiment that would juxtapose these two kinds of political traps. The tape opens a space for dialogue. After it’s over, once the tape is finished, that’s when the real work begins.

MH: The tape also explores the power and politics that exist in intimate spaces.

KT: All of the scenes were improvised. When I was going through the rough-cut transcripts for The Up and the down there were 114 instances of Natasha speaking, 75 instances of Jowita and 73 of Robin. It allowed me to track whose will won out. It showed me who was most attentive and engaged, but also who dominated. It’s fascinating to observe methods of steering conversation, the way interruption is timed, and how stories are told. There’s a great power in curiosity. It’s a present, a gift. When someone’s interested in you it’s exciting. It’s too easy to regard power as a negative force.

MH: Can fringe work remodel this micropolitic, this place between people, effectively?

KT: I think the fringe is vulnerable in its co-optability. The way a Gariné Torossian film can become a rock video and then a corporate ad. It’s a lewd transformation. It’s a microversion of the Einstein problem, how scientific research can lead to atrocity. Hans Haacke said, “Never develop a recognizable style.” For me, the key is in the conceptual allegiance between form and content. You can’t steal that because it only exists in a particular work.

MH: Do you feel your work re-presents moments from your personal life, your interactions with friends?

KT: It’s not that I bring a camera with me everywhere I go, but that the trust we develop allows us to construct fictions. It brings us to the honesty required for me to manufacture a structural diagnosis of our relationship, which becomes the form of the film. WORK (11 min video 1999), for example, features my friend Shary Boyle. Our relationship takes effort; the title is not incidental. Because it’s a day in the life, it shows her working at the office, getting fired, talking with friends. There are ten scenes, each lasting a minute, shown in a succession of split-screens. It’s about the work we do to make the work we love. With natural lighting, real people, two cameras, and long static takes, each double shot was made according to architectural constraints. After Shary agreed to play the focal role, (non-) actors were chosen from her circle of familiars. I cast according to intimacy. The strangers in the video, her boss and lover, are played by real strangers. Each take was about half an hour long, and I searched for the best minute from each scene. There are ten cuts in the video. Peaches (Merrill Nisker) composed beats in her bedroom while watching our video selections. Shary, Merrill, and I became friends. The day the tape was finished we went camping.

MH: How does power circulate in WORK?

KT: The most physical scenes, the singing and sex, are shared in a way that conversation isn’t. Talking joins people here, but also keeps them apart. The real text is body language. Shary embodies an ideal that insists each moment be capitalized, she shows the transformation of daily life into a hyper production of meaning.

MH: Your direction of these scenes is fairly ambient.

KT: I’m almost absent. Directing is about casting, composition, and location. People have been chosen because of their familiarity with one another, and they’re asked to talk on a certain subject. They’re positioned according to the frame’s geometry and then they talk. But when they’re gassing around, that’s usually best, after they’ve exhausted the possibilities of my direction and stop performing themselves.

MH: You’ve made a suite of works with sculptor boyfriend Adrian Blackwell. Could you talk about those?

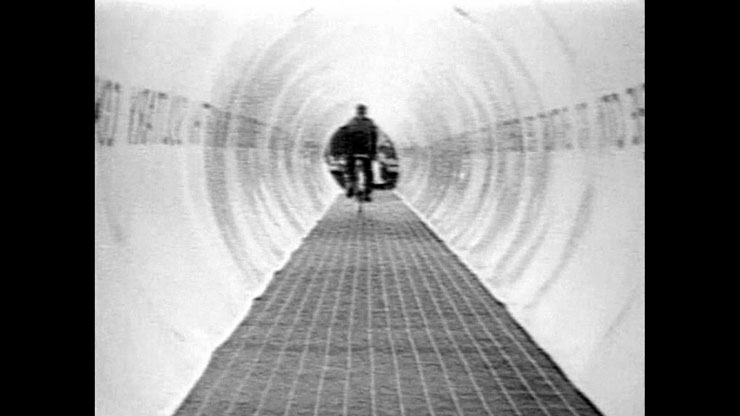

KT: Over a two-year period, Adrian and I participated in a series of collective actions that use architectural scale sculpture as a tool of intervention. These event/constructions operate in various ways, both as euphoric propositional structures and as criticism of the abject conditions of systemic homelessness. During the 1996 Metro Days of Action, a two-day general strike in Toronto, the October Group installed a large inflatable structure over the air vents in front of City Hall. The 150-foot-long transparent tunnel bore a single sentence down each side. Shimmering on clear plastic, it read: “Have mercy, I cry, for the city, to entrust the streets to the greed of developers and to give them alone the right to build is to reduce life to no more than solitary confinement.” The inflatable was a giant, noisy street toy referencing both public institution and temporary home to protest the erosion of our city. This was documented on super-8, then transferred to video to produce October 25th + 26th, 1996 (8 min video 1996).

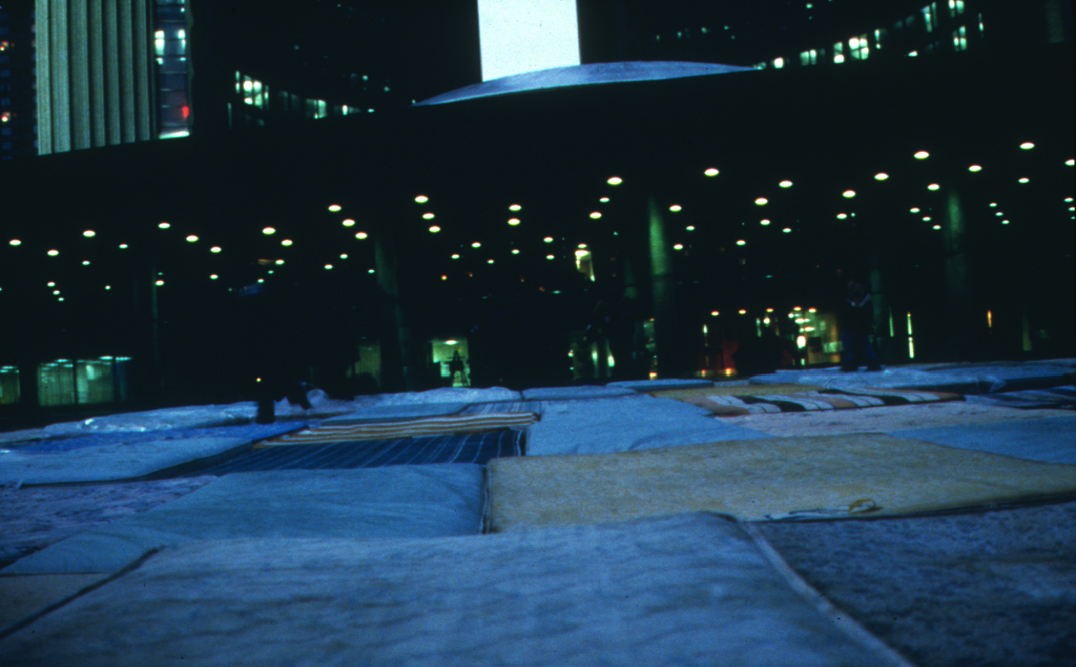

In our next action, the February Group placed sixty-six discarded mattresses on the plaza in front of Toronto City Hall. We stayed for twenty-four hours. The beds were found in late-night garbage explorations around Metro and arranged on the square in a loose matrix. They acted both as a warning of the possible homelessness and migration a megacity could wreak and as a utopian structure that invited citizens to occupy the plaza. The mattress raft was a twenty four-hour sculpture whose surface could be used to sit, run, bounce, or lounge on. Once again, we shot on super-8 and released on video. It’s called Mattress City (with Adrian Blackwell, 8 min video 1998). The beds represent the neighbourhood, but they came from an individual relation. Someone slept here once. Lived here, loved here. Each bed represents a vote or two. It’s important that they’re stained. Even the AIDS quilt was pretty. These beds make a different kind of accusation. The bed is often a site of shame, and this most private of places was delivered to the town square. In the spring, the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty asked a few artists to create individual memorials for the homeless men who had died in and around Allen Gardens, a park and conservatory in the downtown core. The April Group made a Sod Roll for Sean Keegan. Sean was a seventeen-year-old murdered in a parking garage by a john. In response to his death, we cut into the grass and rolled it back; the fresh earth vivid against the green, making a bed, a grave, a sleeping roll. The political backdrop for these projects is the end of a thirty-year span of democratic liberalism in Canada, which developed housing co-ops, free healthcare, a welfare net, and an affordable education complex. Now, with the spectre of international economic competition, the system is under “reconstruction.” The Ontario Provincial government, in an attempt to court multinational investment, has implemented a “Common Sense Revolution.” This involves comprehensive cuts to all social programs, the end of rent control and public housing, and a muzzled local democratic process. The architectures we’ve been making in response argue that safe, affordable housing is a public responsibility, while simultaneously proposing new forms of engaging political space. The October Group project was erected quickly, at night, without permission, and its short lifespan involved negotiation, civil disobedience, and solidarity with union groups. In February we purchased a permit to hold an action in this same public gathering space. We used the fear public officials shared about the impending municipal amalgamations to gain quick approvals for an unusual inhabitation of this symbolic space. We have attempted to inscribe private spaces on the public realm. While clearly referring to “living on the street,” these projects raise questions of political space. For most, the home is the last forum in which people feel they have control. It’s also a stage where status quo modellings play out. The dialogue of domestic space must be made public if we have any hope of undermining conservative power structures. We were interested in creating new forms of protest. Marching, placards, and speakers are too generic. One should be able to protest in as many forms as living (or dying) allows. This has reinvigorated a relationship between artists and the Left. I don’t think community groups were fuelled by the avant-garde properties of our work, but they recognized the power of its media optics. And the energy was palpable, it’s clearly visible in the tapes. One gets the sense of a living culture.

MH: Why make a film?

KT: The event is over but the problem remains. There was media coverage, but representations are fleeting and flawed and don’t belong to us. When you can screen to only two hundred at a time, the work takes longer to circulate, but it gets talked about, and that talking sustains relevance. Mainstream media sound bites have a wide reach and a short lifespan. There’s a different level of care in my making. It might be cruder, but there’s more love and the fantasy that we can transfer euphoria to the audience. The event exists again onscreen. The audience participates again in their willingness to identify.

MH: Sometimes you show in art galleries, sometimes in festivals or co-ops. Which do you prefer? When someone’s interested in you it’s exciting. It’s too easy to regard power as a negative force.

KT: Artist-run centres pay better. The quality of attention that one brings to a gallery is appropriate for short media, which is often conceptually driven and rarely created for the purpose of mere entertainment.

MH: You don’t find galleries elitist?

KT: Almost all fringe screenings are elitist. The hip-hop video artist Art Jones came up from Brooklyn, and it was embarrassing how few black people came to see his work at Pleasure Dome. Artists of colour don’t come to Pleasure Dome unless they are filmmakers who live downtown.

MH: Aren’t you preaching only to the converted?

KT: No. While most of the artists I know are politically astute, very few feel that their work should be political or used for political means. It’s the taboo of didacticism. The fear of generating propaganda and, of course, sheer lack of interest.

MH: While your later work has taken on more overt political questioning, the first five years of your making developed a personal erotics. Do you feel that work is also political?

KT: Is it political to be a raunchy sexpot? Is it political to show your pussy to strangers? Some would say political, others pornographic. When I began making work, the only thing I could manipulate was my body. That’s where I had to start.

MH: You’ve always made work on the cheap. Is that important?

KT: It’s not a totalizing necessity, but it does allow me to communicate with younger makers and people who never thought they could afford to make anything. It’s inspiring to see a fully developed practice, like Steve Reinke’s for instance, that involves very little capital. Besides the effort, of course.

MH: Tell me about She-TV.

KT: It was a public-access cable-television show that ran from 1991 to 99. Women at the Maclean Hunter station were tired of the inequality of access, so we banded together to make television for women by women. My particular mandate was to promote a complete openness of format and genre, duration and production style, which could make experimental television possible. There was no shared aesthetic, but we were all feminists coming from a variety of cultural backgrounds. In the beginning, the collective was dominated by women who needed to shift from academic or journalist pursuits into television production. But by the end, fifty percent of the people involved were artists.

Since 1967, the CRTC demanded that in return for accessing Canadian airwaves, the cable companies would provide citizens with tools for “free speech” by creating production facilities open to anyone. These were used mostly by community groups. In the late sixties and early seventies, public-access TV was wildly eclectic. It featured Kent State from the protest lines, turtle racing, girls rating orgasm — nothing was too intimate or too political. There was an everyday feel soon suppressed because it too reliably provided documentation of dissent. In the ensuing years cable began to look like all the other channels. I became a public-access TV producer because of Paper Tiger TV, which broadcast activist resistance to the Gulf War. This material wasn’t getting airtime on corporate media, which made it appear internationally that Americans were all in support of the war. This resurgence of political intensity brought a generation of practitioners into public space. While cable delivers only 8,000 viewers per program, we received multiple screenings and more audience than we could ever hope for at the local fringe joint. In a 1992 anti-censorship symposium, dub poet Lillian Allen turned us on to the fact that the struggle for access to production and post-production facilities comes before the fight against censorship. It’s easier to censor what hasn’t been made. This is the most effective way to silence entire communities. I began to do interviews with Chris Poulsen, a sign-language instructor at the 519 Community Centre. He had grown up deaf, native, adopted, and gay. A complex set of identities. I thought he would be a good person to talk to about hearing. I also spoke with queer black activist poet Courtnay McFarlane, asking him to participate in an interview about talking and listening, though in the end both interviews turned around race. I made a tape that largely featured Chris but I had a problem shrinking lengthy interviews into sound bites, so I withdrew it from circulation. The interview with Courtnay became Whatever (22 min 1994). The central recurring close-up shows Courtnay talking about growing up black and gay. His recountings are collaged with avant white-girl doings mirror make-ups, girl-on-girl sex in the forest, advertising. The tape is about listening and identification. It’s about the moment you hear someone narrating their experience and how you imagine yourself in exactly the same place. Only it’s impossible to cross racial lines, to truly empathize or understand what it must have been like in that kindergarten class. I wanted to implicate myself in his story, to show how someone like myself, who has a desire to unwrite the colonial program of my own heritage, still misbehaves. My own act, the act of listening, is not enough. But it’s a beginning.

MH: I understood the girl collage material to be a kind of active listening and response to what Courtnay was saying.

KT: Yes, but at same time, it’s more images of white people. How does that help? Basically I’m eliminating his brown face with my white images in my act of concern and identification.

MH: This is the problematic the tape poses to its audience?

KT: Yes. That the invisibility of whiteness was obliterating the view. Again.

MH: You met up with one of my fave writers, Kathy Acker, and turned that conversation into a video.

KT: Kathy Acker in School (8 min video 1997) is comprised of two pieces. The backdrop is an earlier film of mine called School (4 min 1995). It shows headmistress Barbra Fis¸ch disciplining the bad student, played by me. She ties a shoe on my face and spanks me while Donna Summer sings “Love to Love You Baby.” In the centre of School is a cut-out rectangle in the shape of the capital letter I. Kathy Acker is visible inside the I. The original 45 – minute interview is placed inside the four-minute film School without any cutting, using only the fast-forward or rewind buttons. Kathy Acker in School is eight minutes long. It’s an homage to the queen of cutting. She talks about conceptual art, digging herself out of hell, bourgeois narrative, and using myth to make another kind of life possible. Margaret Christakos at Mix Magazine asked me to interview Kathy Acker. I was to show her the work I’d made that was influenced by her. She was watching Sister and School, and I was so nervous that every thirty seconds I took another swig, so by the time the interview started I was completely loaded. I asked about her relation to the New York underground cinema, wanting to uncover this moment of her formative life, knowing she’d been born out of that film scene.

Thorne: I guess what I find alluring and disappointing is this idea that in the sixties you had complete disdain for the St. Mark’s Poetry Group and the cult of subjective truth. Instead you played with a quantity of “I”’s. You juxtaposed fake diary with real diary. You stole. There was a formal commitment in your work that set you apart from the “storytellers,” and now you are moving into terrain that could be described as indistinguishable from theirs … Acker: I reached a point in my life where I was just sick of living in a black hole, only descending to the bottom. I said it’s finally time to do something else: to ascend. To make structures. So I became less interested in this business of tearing everything apart, of saying no, of being angry — and more interested in how I could make. I started looking for ways that didn’t reek of a world I disliked … [Jack Smith] told me he wanted to have a dome in North Africa, a huge dome, and everyone in the world would come to it, a Pleasure Dome, and they’d tell him what they wanted most in the world and then he’d make what they wanted into a film… (from Kathy Acker in School)

When Acker was just 14 she started dating P. Adams Sitney. She would meet up with him and Jack Smith and Brakhage wearing her school uniform. And, of course, I’m dressed in that same uniform in the tape. Neither a whore nor a student. School uniforms are so easy. It’s a place where we can all begin that’s the same. It has the appeal and dystopian qualities of any uniform, but unlike most it prolongs the fantasy of childhood. I still wear them today. I was interested in how all these 30-year-old bisexual dykes were revisiting and appropriating earlier moments of their lives, the queer adolescence they didn’t get to have, at least not in such a gregarious and hyper-sexualized manner. But don’t you think school uniforms are just plain charming? They’re at once respectful and dirty. When my parents left me with my horrible grandmother, she packed me off to an expensive boarding school, but she could only afford one term. She pulled me out and sent me to a slightly cheaper day school, and then the following term to an even more low-rent situation. Each term found me in a new school with a pricy new uniform, until at last, over a span of four years, I wound up in a state school. I have a vast collection of uniforms as a result.

MH: The cinema at times is also like a school, a school for beauty.

KT: Money is easier to target than beauty, poverty is easier to talk about than ugliness. There’s nothing one can do about the way one’s face is genetically constructed. But why are we so attracted to youth? Are we repulsed by our own decay? There’s a series of platitudes that surround the acceptance of dying. Which is what aging is.

MH: You’re showing young and beautiful folks in your recent work. But don’t you think school uniforms are just plain charming? They’re at once respectful and dirty.

KT: I remember Helen Lee saying that beautiful people look normal in cinema. I was appalled. But when I wanted to create images that look like they might co-exist with the mainstream, I felt I had to use beautiful people.

MH: The images that surround us take up inside. It’s not just out there on the screen but inside me. I want to stay young, but my body is telling another story. It’s showing me how to grow old.

KT: Part of what cinema does is celebrate the relation between light and young, clear skin. It doesn’t have a lot of sympathy for saggy old cellulite. It’s one thing to show your funny-looking body when it’s fresh and lithe, but when you get older it takes insane courage. Indie media culture has no Jo Spence, the British photographic artist who made autoportraits after her mastectomy. And she’s very large. What’s crucial is that Spence is middle-aged. Her body is not particularly unusual, but the only time we get to see this is in medical photography or freak shows. The British seem to be more open to that form of beauty than North Americans. I was trembling when I saw Nitrate Kisses by Barbara Hammer. That’s a successful film about aging because you see that love and sex are possible in the end. These two women have done a lot of living, and they lie together on the sunlit floor, finger fucking. You can see their wrinkles, the texture of their skin, their cunts, and it’s not so frightening. It’s sensational. I’ve never seen anything like that between a heterosexual couple. The fearlessness of lesbian culture laid the groundwork for those images to be created and received. “Female heterosexual” is not a subculture. Perhaps it needs to borrow some strategies, to make films about sex and flesh and health and death after thirty-five. To explode fear and the quiet retreat of the aging female into a million displays of desire and decay.

MH: There are moments of queer cinema, like the Hammer film you mentioned, that not only narrate different lives, but narrate them differently. The place of that difference is also a way of saying no, of refusing the occupation of pictures from Command Central. These pictures insist that politics is too important to be left to politicians. Sometimes these marginal pictures, seen by so few, are a very quiet no, barely a whisper. But in this collection of whispers, sometimes, it may be possible to find a way to speak again that most beautiful word in the English language. To invent the word yes for ourselves. To say yes.

Kika Thorne Film /Videography

The Discovery of Canada 4 min b/w video 1990

two (with Mike Hoolboom) 8 min b/w 1990

YOU=Architectural 11 min video 1991

Division 3 min b/w 1991

Fashion 3 min b/w 1992

Whatever 22 min video 1994

Suspicious© (with Kelly O’Brien) 6 min video 1995

School 4 min b/w 1995

Sister 11 min video 1995

Sheet Sculpture (with Adrian Blackwell) 8 min video 1996

October 25th + 26th, 1996 8 min b/w 1996

Intraduction 3 min video 1997

Kathy Acker In School 8 min video 1997

Petscene (a she-tv Collective Production) 27 min video 1998

Yearbook 3 min video 1998

Mattress City (with Adrian Blackwell) 8 min video 1998

Handslap (made with Daniel Borins) 8 min video 1999

WORK 11 min video 1999

Super Spirograph (with Barry Isenor) 5 min video 2000

The Up + the down 5.5 mins video 2001Originally published in: Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2nd edition; Coach House Press, 2001.

Bodies and Desire: The films of Kika Thorne (2000)

The films of Kika Thorne follow a trajectory from private sphere to public. All of her making carries a diary address, each film arising from personal encounters, or as Thorne describes it, just “hanging out.” These casual, low-tech documents of the underclass come armed with a barbed politic, whether the sexy feminism of her early work, or the address to urban homelessness in her more recent efforts. Decliately enacted and finely honed, these are political films which are never strident; their origin in the personal never lapses into solipsism.

While she has used a variety of low-fidelity methods, super-8 has been her most reliable companion, providing both portability and an accessibility of means. Whenever the need arises, the camera can be passed on to participants for their point of view, and its no-budget results serve as example to any hoping to commit their own dreams to emulsion.

The Discovery of Canada (4 minutes 1990) is an allegory which relates a personal dreamscape to nationhood. Photographed in a darkly drawn black and white, Discovery’s fragmented glimpses are propelled by a first-person narration which describes a nighttime walk towards home, and then a recognition she is being followed.

The film’s first image shows two legs rising from the frame’s bottom edge, both resolutely underexposed, glimpsed in half light. They offer the view of legs opened in childbirth, a subjective view of maternity, limbs parted to unveil two bodies drawn from a single source. A brief hand-held shot of a dance follows, the camera and its subject joined in an expressive shake of meat. And then a title appears, painstakingly scratched onto the narrow arena of the super-8 frame. It spells “herself.” This declaration of subjectivity, signed in the filmmaker’s own scrawling script, literalizes a feminist écriture, even as it affirms a woman’s traversal, a bonding of words and places beneath a name only she can utter. After the title a hand-held shot follows, aimed at an urban stretch of dirt filled with the remnants of a broken and discarded glass. As she walks the voice continues: “Suddenly that body came swinging through the doors on a rope and landed in front of me. He had giant shards of glass jutting out of his flesh, small puddles of blood gathering there.” Breaking through her French doors, he arrives with glass lodged in his flesh. As the story progresses there is a suggestion that anyone joining “herself” in this place, the place of her home, would need to come bearing these scars, that any admission would have this toll exacted. These shards are the signs of company, the semiotics of union.

The voice-over continues: “I looked into my bag and pulled out some gold scouring pads and started to lather his cuts. I think he became numb from the pain.” As the voice recites the camera recounts a meeting of friends, two women glimpsed in a strong side light, the camera pouring over moments of their expression with a gaze that is less observation than caress. Lensed in a series of extreme close-ups, Thorne closes in on the ear, organ of admission, allowing us to keep watch over the spiraling shape of mutuality, even as our own hearing is taken over by stories of dysfunction and abuse. The voice continues, “I was still afraid of him even though he was completely helpless by this point, perhaps dead but I knew that he would push and he would find the strength to hurt me. So I looked over and saw an X-acto blade. I thought about picking it up and trying to stab him with it but I knew in my mind’s eye that the flimsy metal would only wobble against his flesh. But I thought if I strike over and over again I could dig away at his back and cut out his heart.”

After a white crossbar divides the image into four equal quadrants, we see a dark chain attached to a buoy in icy water. It tugs at the buoy in a wind inspired yearning, the water sparkling like the glassy shards of the filmer’s walk moments before. The round buoy, appearing like an eye cast adrift in an aqueous humour, is joined to the chain without being part of it – here is another couple attempting to reconcile differences, the line and the circle, the cock and cunt, hauling at cross purposes.

The voice concludes, “I knew this wasn’t the right thing, in fact, I looked down at him, and scooped him into my arms, one closing in on his head the other his ass, and my finger came to rest where the warm hairs circle the asshole.”

Discovery’s narration rises in pitch as it proceeds, its thinning timbre imparting a little girl cadence. Even as the voice draws towards the end of its story, it suggests its own beginnings. At the film’s close the narrator is both mother and child, receding into the body of the mother, the body of language. Her encounter with the intruder is emblematic of this double movement. The stranger is repelled, then accepted. It is this alternating current, between submission and domination, between admission and expulsion, that Thorne would take up in her ensuing personal works, which would more centrally place her own body at the nexus of identity.

Fashion (3 minutes b/w silent 1990) and Division (3 minutes b/w silent 1990) are complementary films that join Thorne and Stephen Butson in performative miniatures. Each film runs the length of a single black and white roll of super-8, each primed on isolated rites of contact that illuminate gender division and power. Fashion is photographed entirely on video and then rescanned off a television monitor. It shows Thorne lying inert throughout, wearing a moiré gown which her companion cuts it away with scissors. Using a variety of crude video techniques – the tape is freeze framed, fast forwarded and rewound – these actions are subject to an electronic review, poring over gestures of female servitude. Thorne sets up a double standard here, appearing as an ultra-passive performer on the one hand, little more than a dressmaker’s doll, but at the same time superimposing the marks of a maker’s control.

In Division clothes are no longer the issue, as both Thorne and Butson appear naked, making out in the bath. Their contact is interrupted only once, in an intertitle that lies between them: “liar.” As the only word in the film, “liar” unleashes a train os associations that folds the film back on itself, turning an innocent bathtub romp into the division of the film’s title. The “lie” relates the filmer’s conflation of power and intimacy. Despite Division’s verité trappings – handheld camerawork, crude lighting and unrehearsed gestures – these intimacies are patently staged, drawn towards the end of their own reproduction, finally borne away by one of its member to authorize and release as her own issue. This is not intimacy, but its staging, its appearance.

You=Architectural (11 minutes b/w 1991) is a reflection on male desire cast in three parts. The first shows a man moving as Thorne’s handheld camera glides alongside. His boxed inventory, storeroom of personality, becomes a metaphor for the displacement of desire, transferred by hand from one domicile to the next. The soundtrack is interrogative, a series of questions its moving image never stops to answer. It asks, “Why did we need your approval? Why did we think if we got it, it would make a difference? Why didn’t we remember that difference was more than just a theory, that we could take advantage of all we learned. Why did we have to get so goddam earnest? Couldn’t we put up a bit of a fight? Why when you entered our bodies we lost our savvy and our styles, our wit? Why didn’t we leave you?” If his moving is figured as the result of actions never glimpsed, as the aftereffect of love , then her questions search out the reasons for this hurried parting.

A hand bearing a stamp impress marks the letter ‘O’ on a scroll of paper, inaugurating the film’s midsection. It shows a woman in close-up kissing and touching a blank wall. Because Thorne has flipped the original footage, the woman’s small gestures towards the wall (kissing and touching) play backwards, just as her face appears upside down. While she peers intimately into its soft blank, the voice-over recounts a story of violation.

“We were at a party when we were introduced and they tell me you’re Tony and I remark, “Oh yeah, your mother and mine were friends once.” And he looks in recognition, laughs and says, “Kika”, and I say, “And you raped me when I was eleven”. Funny how the record stopped after I said that, all the voices stopped though few dared to look over where w e stood. I stare straight into his crown, he’s looking down, or is he looming into my eyes, hungry again for my eleven years? I can see he’s remembering his illicit memory and he’s enjoying it or is it guilt and his lover is standing next him shaking his arm asking, “What the hell is she saying? What the hell is she saying? What the hell is she saying?” And each repetition gets a little less calm because this is all making to much sense. Because this is just a bad dream for her, because a moment in her past is saying yes, yes yes. I’m kicking him in his groin so he won’t have kids to abuse. I took my elbow to his teeth, his face into the wall, the floor. I felt the cartilage snap of his bone, his aqualine nose cum hideous and now people are starting to turn on me. They don’t care if he ever hurt me. Now I’m abusing him and they have to stop it.”

This tale of female revenge relates her actions at a party, in a long delayed reaction to events many years before. Meanwhile, in the image, a woman reclines against a wall, used here as a metaphor for recall. Even as her image is played backwards, she is likewise trying to go back, to return to the pain of her youth. Her image asks how she might touch this place, this memory, without destroying herself. How can she live with this knowledge, with a sex steeped in violation and abuse, without beginning it again now?

The text is recounted by a male voice, though the “I” in the story clearly denotes a woman. Displacing the narrator’s gender, Thorne distances her story, re-routing her desire in order to reclaim it, to take it back from the masculine dissent that first wrested it away from her.

“They say the veil that hides the future from us was woven by an angel of mercy. But what blinds us to our unpredictable past? Why are we hooded as we search amongst its ruins, trapped in the intricate web of motive and action? Novelists of our own lives, making ourselves up from bits of other people, using the dead and living to tell our tale, we tell tales…” (Sin by Josephine Hart)

The solitary hand re-appears and impresses the letter ‘U’ on a blank scroll, initialing the film’s final sequence. Processed by hand as a black and white negative, we watch close-ups of a drafting table. Pencils follow the trued lines of geometrical imperative, the body’s mathematical extensions plotting new homes, new arenas of visibility. On the soundtrack the filmmaker’s voice recounts the story of herself and Neil, a London architect.

“Except for Lloyd’s and Battersea London was architecturally famished, so we shifted our attention to each other’s bodies, and eventually in the pale light of night, me with my underwear down around my ankles squatting on the window ledge, toes gripping the old wood, him with his tongue between my legs and his hand too and I was trying not to breathe so hard, seems like every exhale would lose my grip, and when I came I was flying and screaming. I was face up on the cement two stories below and I knew I was going to die. But maybe I would just be physically broken. And I looked up at Neil’s face, lit by that moon, and I knew what he was thinking.”

The film closes with this engimatic epithet, “I knew what he was thinking.” Hurled from an impoverished London architecture in the grip of sexual delirium, Thorne looks back at the stolid figure of her new lover, framed in old wood. But there is no structure, no place that can contain her desire. So when she relates, “I knew what he was thinking,” she contrasts her own boundless flight with his carefully measured architectural plots, her explosive sexuality with the limits of a desire that seeks its image in the permanence of geometry, in the measured tiles of home.

Each of her three partners evokes a relation to architecture, the first swapping one house for another, the second erecting an architecture of denial and repetition and the third making plans for future domiciles. But while each is associated with and finally contained by the architectures they inhabit, she moves from one to the next, the final image of her flight evoking her escape from male constructions, even as her threat of bodily injury conjures the cost of her freedom.

In 1992, Thorne, along with thirty others, began a women’s-only cable TV collective called SHE/tv. Taking advantage of cable’s mandate to provide community access and programming, SHE/tv wanted to provide an entry point for first-time makers, as well as public space opportunities for artists. Much of Thorne’s work over the next four years would be made at cable television, though it would bear little resemblance to other offerings on the tube, as it remained formally inventive and steadfastly political.

Whatever (21 minutes 1994) takes up the thorny issues of race and identity in an elegant weave of experimental portrait, racial exposition, diary work, and “coming out” film. The effect is an inventory of personal experience framed within questions of colour and its attendant host of invisible ideologies. Rife with a lyrical exposition, Whatever takes its cue from the talking head tales of Courtnay McFarlane, a young black gay male who speaks of his lost patois, the importance of a black lover for him, and the invisibility of blacks in gay porn. Animated, funny and reflective, McFarlane’s insistence on the political motivations behind private conceits echo through the surrounding collage: a loosely knit portrait of white girls at play. We see Rashid brushing her hair while Prince blares on the beatbox, a swinging woman shown in negative reciting the fifty states of the union, Janet in the bath, another playing solitaire with girlie cards until she herself becomes one of their number, two women making love in the forest.

Interleaved with McFarlane’s racial expositions, it is impossible not to see these friends at play as “white,” engaged in the reproduction of whiteness, even as their gestures appear intimate, everyday, commonplace. Thorne closes her tape with a pair of doll scenarios. In the first, McFarlane’s poem scrolls past the black dolls he has collected to remind him of our racist heritage, while in the second a woman plays in fascinated identification with a hand-painted doll, kissing and then torturing it, seeking in it a model for her own experience. Thorne suggests that Whatever, and by extension, artist’s film and video, is also a plaything, a doll offering models of possible experience and interaction.

Suspicious (6 minutes 1995), a collaboration with fellow SHE/tv member Kelly O’Brien, was made in response to the surge of identity-based politics that swept the Canadian art scene in the early ‘90s. While a grassroots, artist-run movement had flourished in the previous two decades, providing a national web of specialized galleries, equipment access centres and screening venues, the notable absence of people of colour pointed to a systemic exclusion which challenged the traditional constituencies of DIY culture. In Suspicious a rapidly edited collage of nine people pronounce their own identities (gay, dyke, South Asian, person-of-colour, Jewish), but then begin to unravel these easy namings. Scott Beveridge insists that the only thing he has in common with the Gay Republican Party or those fighting to include openly gay personnel in the military, is that he sucks dick. Laura Cowell would still consider herself a dyke even if she was dating a guy. Proceeding via sound bite and metaphorical cut-aways (dildo collage, rolling up a steel fence, gay rights march), Suspicious’s kinetic vortex of intimacies lends fresh perspectives to the often polarized debates on race, gender and identity. Young, cheeky and articulate, the nine folks gathered here demonstrate that politics is a question of choices made very day, as they seek new words for experiences not yet dreamed of.

October 25 + 26th (8 minutes 1997) documents an agit-prop protests against the Tory government, whose rapid succession of hospital closures, welfare cuts and elimination of rent controls ld to Canada’s largest ever political rally, the Metro Days of Action. Architects and artists (including Thorne), naming themselves the October Group, built a 150-foot inflatable sculpture and raised it just outside city hall as part of the day’s activities, and Thorne’s tape documents the sculpture’s manufacture and deployment. A long plastic tube given shape by a series of cold air vents bears the following message stenciled a cross its length: “Have mercy I cry for the city; to entrust the streets to the greed of developers and to give them alone the right to build is to reduce life to no more than solitary confinement.” Photographed in a careening, off-the-cuff style in super-8, its accretion of details is moving and exact, depicting the comaraderie of the group, and the sheer delight many took in walking within its temporary walls. At film’s end it is razored apart, providing a climax both modest and exhilarating. In short order it is folded up and put away, as the October Group joined the crowds gathered in protest.

A year later, the group would gather again, responding in protest to the provincial government’s continuing inaction over the crisis in affordable housing. Returning to city hall, they laid down sixty-six mattresses in a large grid, a public sculpture of roofless beds which stood in mute protest. As TV crews gathered, Thorne proceeded to document the event in her own inimitable fashion, passing the camera around to onlookers and friends, frolicking with the young and curious across the sea of soft fabrics. Mattress City (8 minutes 1998) begins with a pixilated romp over house exteriors before a traveling shot brings us into the city of Toronto. A series of superimposed titles names the six municipalities of Toronto, suggesting each has developed particular strategies to deal with the problem of housing. In 1998, the provincial government decided to amalgamate these six into a single “megacity.” The day before the public plebiscite the October Group laid down their public sculpture. “It was proposed as both warning of the homelessness and migration a megacity could create, and a utopian structure inviting citizens to occupy this public space.” After these titles the film shifts into black and white, showing mattresses being load onto cars, the communal work of laying them out, strangers jumping on the mattresses, and the group sleeping overnight (a tarp allowed its intrepid members to spend the night). Finally the mattresses are towed away, leading us to a series of titles which narrate the overwhelming vote (76%) against amalgamation. The megacity was created in spite of the vote on January 1, 1998.

Kathy Acker in School (8 minutes 1997) features an interview with the post-punk iconoclast, an author renowned for her text grafts, her sexual frankness, and her unflinching ability to mine the abyss. Acker appears in an I-shaped matte, speaking in blue-toned close-up. She tells of hr early interactions with American underground film, how jack Smith hoped to build a great pleasure dome in North Africa, invite strangers to come and tell him what they wanted most, which he would then make into a film. Acker’s image is keyed over a schoolgirl romp, Thorne’s own School (3 minutes 1995). It features a grainy duet of schoolgirls (played by Headmistress Barbra Fisch and the filmmaker). The two are dominant and submissive, the student shines shoes before having one strapped to her face, waiting for punishment, she opens her hands for whipping, then bends over a chair to have her ass spanked.

Both images shuttle back and forth, there are no edits here, as the I-matte examines and re-writes Acker’s face, searching for anecdotes, or re-cues the s/m punishments of the girls. Laid over all of it Donna Summer croons, “Love to love you baby.” Acker concludes: “I reached the point in my life where I got sick of living in a black hole. It’s finally time to do something else. To ascend. To make structure. So I became less interested in tearing everything apart and being angry. I started looking for ways to make that didn’t reek of a world I disliked.”

The title of Intraduction (3 minutes 1997) is a self-made word conjuring an in-between space of introduction and passage. Its very illegibility suggests a troubling of language’s usual transparency, especially in this transfigured space of a TV talking head. Begun with a clear red screen we hear a voice reciting a German text, and then its translation. It concerns the reception of Feud’s theories on childhood sexuality. Freud remarks on the difference between genital and sexual pleasure, insisting that sexuality begins immediately after birth. Like the transmission of Freud’s original texts, one is forced to contend with a halting translation of its reception. The translator (clearly not a professional), slowly comes into focus. But this image, shot hand-held, in ever-changing hues and ones, leads ub back to the subjectivity of expression, and the difference between the written word and its oral performance.

Her next video gesture Work (11 minutes 1999) follows in episodic fashion the life of an underemployed twentysomething female (winningly played by artist Shary Boyle). Following a structural conceit, ach shot lasts exactly a minute, and is lensed from two distinct perspectives, which appear simultaneously on two adjacent screens within the frame. But while the structure is rigid the performances are unrehearsed and improvisatory, lending an easy naturalness to each vignette. Work proceeds from the young woman’s data entry job to news from her boss that she is fired. She lies motionless on a couch letting a thrash metal riff wash over her, hangs out with friends, goes to a party, meets a guy, and makes out with him. Contrasting the physical intimacy of her new boyfriend with the aural intimacies of her girlfriends, Thorne leaves the end deliberately unresolved. As in life, she suggests, there are no tidy endings here, no possibility of closure, only the ongoing struggle to live. To work.

Thorne’s double vision representation, often offering us simultaneous front and side views of the same action, keeps us keenly aware of the act of framing, of how this woman’s friends, associates, and employment possibilities all work to place and define her. Context is content, Thorne suggests, in this frank merging of public and private spheres. Her protagonist’s youth is clearly related to her job experiences, just as her previous romantic attachments form the basis for her new love. In trying to find her own image in this mosaic of identities, she finds a part of herself mirrored in each of her interactions, and so a self begins to emerge which is both refined and redefined in each of its interactions.

If Thorne’s early work deconstructed the machinations of power and gender, insistently viewed in a personal setting, her work since the mid-1990s has taken on a broader political cast. Turning her low-tech documentary techniques towards an exploration of state power, race, and the bisexual kingdom, Throne continues to draft one of the most intriguing and bravely personal oeuvres of the fringe.

Originally published in: Lux, ed. Steve Reinke and Tom Taylor, 2000.