Hand Cranked: A Conversation with filmmaker Lee Krist by Alex Mackenzie

Alex MacKenzie: Maybe we can start off by discussing your body of work and how hand cranked material fits into it. Is this a natural progression from other pursuits?

Lee Krist: My use of a hand cranked camera originated in my current experimentations with making photographic emulsions. I hand process all of my films so I gradually got more and more interested in photochemistry. Having a chemistry lab at my disposal was also a big asset. But the 35mm hand crank route was a result of needing to work with a durable, large format film camera that could basically pass anything and everything through its gate. In addition to the long exposure, my hand cranked camera allowed me the technical capabilities to pursue making my own film stock.

AM: You have been making films since you were sixteen. What initially turned you on to this medium? Is your family background an artistic one?

LK: I always wanted to be a painter. I have very poor hand-eye coordination, so the fine arts were tough for me. I think what really turned me onto film as opposed to video was the fact that you could shake the camera, do stop motion and it wouldn’t look as nauseating as it would on video. My family isn’t artistic—good food, but no art.

AM: Are you in communication with anyone else creating their own emulsions, or is this entirely your domain?

LK: I hear bits and pieces about people doing similar things. But it’s mostly second hand news. I know many people have tried it, but I am quite unaware of the extent of their photochemical achievements.

AM: Could you speak a bit more about the actual creation of film emulsion? How does that work exactly (okay, not exactly, but generally…)?

LK: Well, to simplify it, all you have to do is sensitize silver and have it properly suspended on a surface. Something that I have yet to successfully achieve. If I were a photographer, my life would be so easy.

AM: I understand that you work at a film lab and that it was a dream of yours to pursue this. Does the content of lab contracts (commercial work) matter to you, or is it the process itself that takes precedent? How much are you keeping this job to have access to lab chemicals and how much do you really love it?

LK: I like working with film; touching it, handling it in a very inhuman way. I’m not into it for the chemical perks, it holds a special craft appeal, like I’m preparing for the future. I don’t really have to deal with people or if I do they are just students. The only troublesome things about the job are the environmental and carcinogenic elements.

AM: Your films seem very personal, intimate and fascinated by a closed system of elements. How do the subject of your films and the techniques you pursue cross-pollinate? How much is serendipity a desired and/or incidental factor in this (both the subject and the technique)?

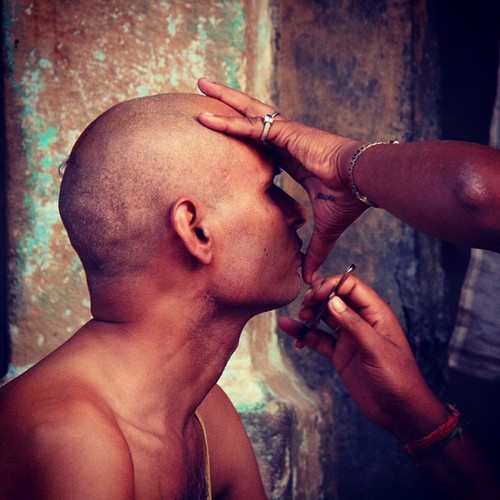

LK: Wow! I really like the closed system of elements metaphor. It’s a good euphemism for what I do. For the portrait series, the subject matter was very grounded in the technical situation that I was in. My work was previously comprised of landscape and abstract imagery. I was paralyzed by the idea of shooting on precious and time consumptive stock. So the most logical approach was to film things that were personally.

AM: I like that both the film stock and the film subject become sacred. It seems that both the technical and the conceptual spring from limitations inherent in the medium: economics, durability, etc. Do you find the limitations inspiring, even necessary?

LK: For me it’s not the limitations themselves that are inspiring but my personal response to them: the attempt to work and struggle within the confines of a specific situation and achieve personal satisfaction with the results, as if it was my original intention.

AM: How important is the necessary “in-person” element to your presentations? Is it exciting, disconcerting, primary? Is this as much a part of the “piece” as the making of it?

LK: It is one of those unexpected surprises that you don’t think you would like until you experience it. It has enriched my life tenfold. It drew me out of the hermetic filmmaking mode that is quite rampant in experimental work. It’s nice to bring things to basics and be able to show people your films as an extension of yourself and the life that surrounds you. It makes the experience of being an artist more tangible.

AM: How specifically performative is your work? Do you integrate the projector set-up in the audience somehow? How much do you think the audience is watching you instead of your work and is that okay with you?

LK: I feel my work could be more performative. Right now, it’s at the simple “show people your films” stage. I try and set myself up in the middle of an audience. That way it doesn’t feel like everyone is watching me and it makes me less nervous. I’m okay with people watching me crank instead of paying strict attention to my films because when you think about it, how many times do people get to watch someone hand crank a projector? It’s reassuring to see the combination of the two.

AM: You choose to work with these limited tools and so are inspired by your responses to them, but you actually set up these limitations in the first place. If you had, for example, chosen the video medium, this wouldn’t come up. Nor would you be pursuing anything resembling what you are doing with your work now. It seems you are making a very conscious decision to limit yourself in a very specific way. I guess it leads back to that question of responsibility and the role of serendipity or chance-results when you create work. Could you speak about that?

LK: I don’t see responsibility and serendipity as being necessarily bi-polar.

AM: I agree, they are not opposite ends of the spectrum. I’m still curious about the drive you feel when creating work. Do you experiment with a “who knows what will happen next” attitude, achieve certain results and then refine? Or do you seek out something very specific, get results and refine? Or keep trying until you get what you want? How much is chance and how much planning?

LK: I have very specific visual intentions for my films, I aim at perfection but what happens is another story. If I ever got what I want I’m not so sure I would be pleased with it. In terms of my work structure, I tend to have a more pseudo-scientific process. I don’t get specific with certain projects but I do have a general intent that provides me with various results that I couldn’t repeat if I wanted to.

AM: Could you explain The Big Film Cycle? Are there more than one?

LK: The Big Film Cycle is just a name for the series of 35mm films that I present. At present it encompasses five films and will include more films upon their completion. I prefer to think of it as a series. I’m not quite sure how the cycle came to be. I think Stephen [Stephen Kent Jusick, New York based curator] wrote it up that way for the Daily News. I prefer it were called Big Film.

AM: Given the form and technique involved, how concerned are you about the preservation of the films you make? Do you see them as having a limited life cycle and ephemeral in nature or do you see preservation as important/necessary? Are the films you present reversal or do you make prints?

LK: I’m concerned enough to panic about only having and showing originals but not enough to do anything about it. Everything I present is camera originals. And the first few scratches hurt but after a while it just becomes a choice you have to make: show films or save them. I should make prints, but if being a printer at a lab has taught me anything, it’s that when it comes to making prints there is no such thing as exact mechanical reproduction. It would be so hard just to get the various exposures right, let alone the hand processed colors. That leaves me with the film originals. I guess it gives the films an ephemeral quality that is not usually present in most work. They aren’t going to last, but they might as well go out with a bang then as vinaigrette. I can imagine a time for restoration later, though the purpose wouldn’t necessarily be to reproduce the work per se, but to partially capture some form of it for later recollection.

AM: I’m interested in the “dead media” qualities of your work. Do you feel that label references your work? And to what extent are the technical apparatus that we use changing? Or is it just the way we receive and process information that is changing?

LK: I feel that my work is very much located in the present and is involved in a discourse that questions how we use certain technologies and our relationship to them. And I feel this relates to questions concerning my transgender identity.

AM: I agree with you that the use of so-called outmoded technologies is not a harkening back to the past, but rather a way of examining the present, a reaction to the modes of information processing available to us today. I’ve worked with super-8 cartridge projectors not because they are hip retro items, but because they do what I need them to do, which is to create filmic images that I can quickly switch between without having to reload projectors. While this is now possible with videodisc technology, it is not possible economically. And so in a way both you and I are reacting to economics at a certain level too, obviously in combination with aesthetic interests.

As with much of the successful experimental work out there, I believe your work challenges the viewer/audience to reconsider what is a “good” image and how “standards” are in fact an economic ploy and cop out. But I particularly like that your work exists outside of this realm and, far from being a reaction, actually exists on its own terms (which is far more interesting) while creating discourse.

I am curious to know how much gender issues play into your work and how you feel about the pigeonholing of work that is “gay”, “queer” or “transgendered” in festivals which base content on sexual orientation. How does your trans identity affect or inform your work?

LK: In terms of the pigeonholing of certain work, this just creates a queer ghetto that no one wants you to get out of. While those structures of queer film festivals are vital in challenging the dominance of heteronormative experience in film, it is vital that we go further: in addition to questioning the messages in media’s representation of society, also question the medium itself and how we use it. I find it interesting to explore ideas of how my trans identity and experience informs the way in which I process information and how it affects my aesthetic sensibility and the overall imagery of my work. For me it feels that “normal” ie. mainstream filmic or even narrative forms of film just don’t do it for me in terms of capturing the whole “what it’s like to be alive” thing. Many attempts at presenting life experiences on film are just too stifling. I find the majority of experimental films stifling in their specificity when they address issues of gender and sexuality. It puzzles me the extent to which people feel that these issues can be easily translated into information that can be processed. In my work I try and let things speak for themselves. And while I find it hard to articulate the queer elements of my work, they are there.

AM: With regards to your transgender identity, do you see the struggle you have with identifying the queer elements of your work as part of a greater problem, that there is no recognized language to put these questions into?

LK: Films that deal with queer matters in implicit, subtle ways are still hard to cope with. Queer subject matter is readily identifiable, but in terms of aesthetic sensibility, or autobiography, audiences are reluctant to locate it. Usually people take the easy way out and try to ignore it and place the work in a very heteronormative context. This has certainly brought to light the way in which people approach my films.

AM: Could this tension be the driving force behind your work? Is your work an attempt to invent this language?

LK: Yes, my work is part of a drive to invent an appropriate filmic language. One that correlates with my experience of the world. Right now I feel rather comfortable in my current style. My previous work was much more abstract. Now I feel that I have achieved a pretty good balance between abstract and documentary imagery.

AM: Can you tell me about some work out there—queer or otherwise—that speaks to you?

LK: In terms of queer work I have recently begun looking into the work of Roger Jacoby. He made a lot of hand-processed film in the seventies. Unfortunately he died very early in the AIDS epidemic. Outside of his contemporaries, Jacoby’s work is not that widely known. I personally have seen only bits and pieces, but I can personally relate to his approach to hand processing. I look forward to studying his work….

(4 years pass)

AM: It has been a while Lee, what have you been up to lately?

LK: The film I am currently working on is called Tableaux Vivant, which is French for group tableau. I don’t know French, it was a random dictionary fortune that I received on my birthday quite some time ago. I’ve exhibited filmstrips from this body of work in an installation of the same name. It’s still in the shooting phase. The film is a return to the landscape imagery of my previous work, but also expanding the notion of portraiture. I am interested in working with imagery that explores the relationship between self and place. My work is getting more and more autobiographical.

AM: In your earlier portrait works, this self/place idea is also very present. Could you talk about your autobiographical approach?

LK: I view all art as autobiographical regardless of its subject matter, so for me the question is how best to achieve the level of autobiography I want the piece to have. It’s something that continually shifts in my work. In the case of landscapes, my primary focus is to meditatively engage with spaces of great beauty. This provides me with endless fuel to go through the parts of life that aren’t as sweet. When I work in portraiture it’s more of an exercise in self-forgetting, stumbling attempts to relate to people through my work.

AM: Why your recent gallery installation approach to exhibition?

LK: Tableaux Vivant as a film installation arose out of wanting to show my friends in Portland, Oregon what I was working on but not being able to project the work for them. I was offered the space and opportunity to do a film installation in town. I wanted to show people how I work with film mainly as a transparency. I rarely project my work while creating it. I mainly view it by hanging it in front of my windows. So the installation is a recreation of my experience with the film. It is very basic: just filmstrips hanging from a pole illuminated by a film projector playing a loop of black flicker. So when you view the filmstrips there is this black flicker in the background, replicating the moment of blackness that occurs in film projection, but also referencing memory and the idea that these images come out of the blackness of memory.

AM: I know you are planning on step printing some of your past works so that they can be presented on conventional 35mm projection equipment (ie not hand cranked). Has the in-person presentation of your work become less of a priority?

LK: As an artist I’m trying to do new things with my work, and to be honest, I’m tired of hand cranking my films, lugging myself around the country, the technical hassles of working with a non-standard projector… I’m tired of the obscurity my work has because I can’t engage in the same channels of exhibition as other experimental filmmakers. I want to do new things and I don’t feel that desire conflicts with the aesthetics of my past work. The Big Film Cycle is arriving at a slow but steady conclusion. While I am still exhibiting the work, in terms of production I still have to finish up one or two portraits that have been left undone. The performative aspect of the screenings are part blessing and part hardship as with most things in life.

AM: Does this flexibility speak to a desire for a many-versioned body of work?

LK: Yes, I would love to have that option, to have my work available to screen without my presence in the same manner as Jack Smith’s work or Peggy Ahwesh’s Pittsburgh Trilogies.

AM: As serendipity and chance inevitably play into the presentation of “live” work, what determines your choices in the step-printing process?

LK: My main challenge will be the replication of motion and how to accurately reproduce the color and texture of the hand processing. I don’t feel it’s a compromise because I think of these prints as documenting my work. While they will have a life of their own , they will not be exact replicas, I look forward to the opportunity to creatively fashion the material in a new form. My ideas on how this will be achieved will become more apparent once I start the process and explore the tools. That said, I don’t think anything could be as sacred as the originals. At this preliminary stage, the aspect that I find the most exciting is finally being able to watch my work projected on a big screen.

AM: We spoke in the past about the ephemeral nature of this work, the fact that originals are being projected and decomposed while they’re being shown. With this move to duplicate prints, has your interest in legacy and/or preservation shifted?

LK: The idea to duplicate my work came about through an offer from the LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) film co-operative to use their newly acquired Oxberry camera. Up until that point the execution of such a project was not on my horizon because I did not have or fathom access to equipment that would allow me to preserve my work. I don’t feel that it is a shift since I still work on and project reversal films. Ever since I began making films my primary focus was to create a working method that would allow me to make films without any financial restrictions. As an artist, when I confront the choice of what film stock and processing method to use, I am continually drawn to the reversal process. I feel that the quality of reversal stock is unparalleled and—compared to negative—I just enjoy processing reversal more.