Sex and Cerebral Palsy by Linda Feesey

In Sex and Cerebral Palsy (11:40 minutes BETA SP 2000) Feesey’s opening titles announce: “Cerebral palsy is a term used to describe a neurological condition affecting motor function and muscle co-ordination. Cerebral palsy is thought to be the result of an injury to the developing brain which occurs during birth.” Using a variety of video post-production magics, badgirl Linda Feesey rescans a pair of couples whose desires have not been buried by their disabilities. On the contrary, both assure us, they think about sex all the time. “I am a sex symbol,” points out Frank Moore on the spellboard he nods his head towards, the large pointer/paintbrush rising out of his forehead granting him access to the prison house of language. Sometimes it’s enough for him to mark out a couple of letters and his partner quickly fills in the rest, acting as shorthand/translator, a conduit to his world of art and artists, stepping lightly over words he labours to touch.

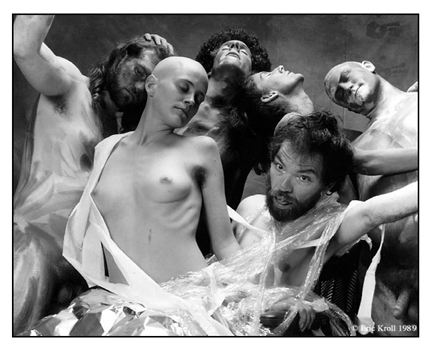

Frank sits in a wheelchair, his arms lying helplessly, uselessly in his lap. And always he is smiling, or laughing, as if his very evident inabilities have forced him to undertake a vocation, a calling even, left behind by those with more useful bodies, and more practical inclinations. Of course this is just a movie, we see a few seconds of what someone does all their life, and this traumatic reduction, this compression of time and elevation of gesture, the camera’s close-ups delivering outsized events of the body as iconic landscapes, continents of desire colliding and falling apart, all this may be an illusion. Is this why he is smiling? The camera is condemned to surfaces, to judging every book by its cover, and Moore’s hilarity may derive at least in part by his realization that the joke is on the viewer, that his feelings are finally unsupportable on emulsion, certainly not by the naked eye. No amount of magnification, no theory of montage can wrest this secret from him (what does it mean to live in this body?), which he carries with abandon into a scene of great intimacy with his partner Linda. She climbs up over him in a romp of multiple exposures with a smile breaking over her face as well. (Is it a smile of pleasure or the semi-embarrassed smile that so often reaches the camera by those unused to its monocular exposures?)

Her nipples, his cock, are erect, and when Feesey asks him if she can see him squirt she says it’s too late and laughs, their rhythms will not be tied to reproduction, there is something left for the two of them after all. In a previous scene, witnessed in a series of blurred overlays, a couple of men lay over Moore, the ultimate bottom, ready for anything. This body is for sharing, for opening, to touch. Caught in a frenzied accretion of glances these performative gestures act as prelude to a longer, though hardly leisurely, coupling between man and wife, whose union is only the beginning of a new and very public kind of sexuality, which insists on demonstration and display. Traditional borders are shattered here, between self and other, married and non-married, gay and straight, this queerverse of desire asking that each of us rethink our own bodies, those territories of the self which form convenient enclosures of personality.

After Frank and Linda the camera makes its way into an art gallery, scoping out a series of paintings (landscapes and portraits) before arriving at visual artist Anne Abbott. Like Moore, she also has cerebral palsy. Tapping out keys on her computer, she waits for it to register sentences before announcing in computer-talk: “I think I’m more interested in sex but society doesn’t think I should have it. Let me count the ways.” And then she does. The camera is close-up and intimate, the pace leisurely, the long space between questions (never heard) allowed to linger on her painfully crossed arms, a single finger stabbing at the keyboard, her mouth in perpetual motion, unable to say the words, but smiling, laughing, regaling us with hilarity.

“I think about sex all the time. Like 99 percent of the time. Mostly because it feels wonderful and the closeness you get. I mean, masturbation feels wonderful too but you don’t get that closeness. There’s still something about having a man looking at you in that special way, wanting you, desiring you, that’s like nothing else.” And then they are naked, licking and touching, a moment of sheer joy passes over her face before he lifts her onto the bed. While they make themselves ‘available’ to the camera, which is very close throughout, they seem entirely, at the same time, into each other, the pleasure of this act, or acting, aroused, wet, hard and then he enters her from behind, her toes curled up, the eyes closed now and he comes and wipes it off of her.

Moments later she lies in bed, naked and comfortable and happy while Roy, also naked, sits in a chair and raps, a plain looking man in glasses. He’s someone who looks like your neighbour, not too this or that, he’s just a man in love that’s all. “She’s a very nice person and has a great sense of humour, just a wonderful person.” Homilies. Tried and truisms. He hasn’t been here a thousand times before, learned to perform himself in front of the camera. Of course she laughs, her arms thrown behind her head, abandoned, she mouths something we don’t understand, but perhaps he does, because he bends over to kiss her. And then the scene, their time onscreen, is over. Feesey returns one last time to Frank and Linda, sitting beside one another, Frank pointing out the letters which provide the closing moment of this portrait. “I think of my whole life as erotic.”