Your Song is Killing Me (2013)

How does the saying goes? That the song is catchy. Like a virus. Like a contagion. It’s something that, in the modern parlance, “goes viral.” All kinds of things go viral these days – Saudi women driving and skating dogs for instance. But the life of songs cuts a little deeper (Or is it too late to speak of depth? Is that only a nostalgia for the lives we used to lead, before our emotions could exist as mercator projections on social media?), a little closer to the quick. What does it mean to catch a song, to be caught by a melody? And what does that platinum selling singalong have to do with what I want, the good life, the fine thing that’s waiting for me right around the corner.

The voice carries along the breeze, the wind, the breath. It arrives on the inhale. You exhale the notes and I inhale them, I take them into the body where they become a part of me. The music isn’t out there, or it’s not only out there, it’s also in here. It’s your million selling single, but it’s also my tune, the one I’m already falling into step with. It’s my dance partner now. My compulsive, like-it-or-not, repeatable emoticon. Perhaps it’s a way to make a picture of my desire before I can get to it. Why don’t I lay back into the uneasy chair and let you do all the work, dad? You call the tune and I’ll hum right along. The music finds its way into the body via a hook, in the industry parlance, the hook catches on some moment of tissue, some firing synapse, and then it can restlessly replay itself there. First there’s the hook, and then the need to repeat. I guess that’s what puts the popular into popular music. The repetition. No repetition equals no popularity. No repetition means the underground, that’s your friend’s basement tapes, the underground economy that isn’t really an economy. But for music to become popular it relies on repeating, and this repeating is both the financial foundation and the measurement of desire. And if it’s what we want is, the community buy in can become common sense, no matter how unsensical the project might be (slavery used to be common sense too). The popular tune arrives front loaded with questions: how much do you want me? How many times are you gonna play me? How much can you afford?

Who better to weigh in on these irresistible tunes than goofball Swiss iconoclast Elisabeth Charlotte “Pipilotti” Rist. Her DIY, low fi outings come dressed up in hand-me-down clothes. They are sexy, no budget shorts about sex and music and fun that came in eye popping colours. In 1997 she gained international prominence by copping the honcho prize at the Venice Biennalle, but she’s kept her work small and burning and alive, following her instincts, keeping her questions close to the body, where they belong.

Pipilloti has been concerned all along with wanting, and how some of what I want arrives so breezily in a song. That the geography I call myself is made up of qualities, fantasies, even genetics, that arrive from somewhere else. Like popular songs for instance. Once I’ve heard it, I can’t help singing it. Once I’ve seen your face, I can’t wanting to see it again. What do you all that exactly — poison or cure?

In her low fi, karoki-inspired haunting, I’m a Victim of This Song (5:06 minutes 1995), she sets up a series of duets that hum between high and low. Clouds move quickly across a blue sky, white and billowing, their softness an invitation to ease and lightness. Time compression is used to hurry their passage, though this fast motion is deployed not to give the sense of an anxious haste, but a langorous abundance. Superimposed over the clouds is a trail of staggered video entrails, remnants of a former cutting edge technology that now appear quaintly out of date, signs of a former utopia. This is where the future used to be, this is what I used to long for. The artist reaches back for this old technology (the high place that is now the low place) knowing that we can read it as the past of the future. She makes a place for us as a viewer, she knows that we know. We’re all in this together. The affect this shared knowing creates is an ease and security, a personal comfort that is also collective, a place of belonging.

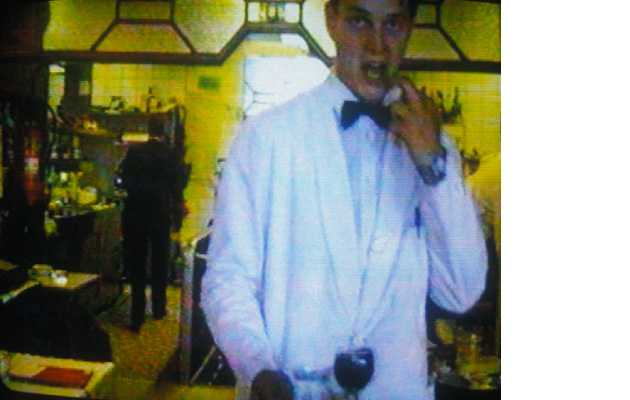

The visual dance partner in this duet is a suite of shots made in a hotel café. Shot on a grim and lightless day, the camera is held low as the artist “shoots from the hip.” Her casual and careening pans are arrested by a slight slow motion, which both preserve the sense of a body moving, while granting that body a slightly ethereal presence, dulling the edge of its presence. This softening is a way of inviting and lulling the viewer, even as the drab colours and unrehearsed mise-en-scene repel. I want you and I don’t want you.

Musically, the high place of the clouds is echoed by the instrumental track heard throughout the tape, Chris Isaac’s Wicked Game. Its pace is similarly lush and langorous, propelled by a reverb drenched guitar twang whose rounded edges recall the cloudy skies passing overhead. The music is tonal, carefully produced, rich, and the affect (if one might be predisposed to enjoy this kind of music) produced is one of luxury (those good microphones cost a lot of money), indolence, longing (the old capitalist question: why does my so-muchness make me want even more?).

The song’s title announces the artist’s project. No need for hyper conceptual difficulties here, I’m just trying to figure out what I want. But what keeps getting in the way is your Wicked Game of smoothness, those soft lulling choruses putting whatever I might have wanted to sleep. In place of my desire, I have yours. If only I could have yours. If only that would do.

What a wicked game you played to make me feel this way

What a wicked thing to do to let me dream of you

What a wicked thing to say you never felt this way

What a wicked thing to do to make me dream of you

Wicked Game by Chris Isaak

“…fantasies of satisfaction are defenses against desiring, the attempt in fantasy to take the risk out of desire; or to put in more Kleinian language, fantasies of satisfaction are attacks on desire; they are, in fact, against desiring… clues to our fears about desiring.” Adam Phillips, Missing Out p. 143

Unlike the song’s precise meter and verse-chorus-verse structure, the restaurant shots appear random and unmotivated, people sit at tables eating, others enter the restaurant and leave it, likewise they enter and exit the frame. Why do we see people at the table near the door, but not in the corner of the room? They could be anyone. We could be anywhere. There is almost no editing in the restaurant scenes, which might give the sense of “real time,” even “honesty” (I have nothing to hide) and with it an affect of immediacy, a shared present, an intimacy of time. But because of the slight slow motion, real time is converted into retrospective time. In this cover version, there is nothing to see for the first time, we can only see again, from the vantage of the rear view mirror, looking back.

The artist’s mediating hand is everywhere in evidence, from the sped up clouds of the high place, to the slowed-down restaurant encounters of the low place, from the video synthesis/blue screen photos appearing in the sky, to the gestural camera work at the eatery. As the camera pans across the empty coat rack of the restaurant, or a trio of lights illuminating a drab tree painting, we can feel the body that is holding the camera moving. We are with you, the camera is saying, as it shifts the field of view. I am seeing what you are seeing. Rist manages this identification of eye and camera with a light touch, she points us at the kitchen, a waiter adjusting his tie, serving trays stacked. She is interested in producing a picture, but also in showing us how the picture is being produced. The affect once again is one of complicity — we’re all in this together, we’re all hip to the joke.

And then a second voice (also the artist’s) rises as if in answer to the first. If the first voice is trying to follow along, gamely karaoke-ing her way even through the muffed notes, the high places in the singing register that she will never reach, casually mangling the song. But the second singing dumps any pretense of going with the flow. The artist screams out her frustration in a repetition of the song’s refrained chorus No I don’t want to fall in love, though the track is dialed down, so the loud voice is not loud at all, but a few ticks lower than the other “proper voice.” It is the voice of a fandom gone wrong, no longer content to play the Wicked Game, no longer buying in. Here is the revenge fantasy lying inside each satisfaction. You made me want what you want, but once I got it, my hands still feel empty. My skin isn’t poreless enough, my ass isn’t tight enough, my lips aren’t kissable enough. I can’t live inside your pictures, your tunes hurt me, the desire you’re jukeboxing me into is making me crazy. Can’t you leave those loops behind and let me find my own music, stumbling and shrill and hang cooked as it might be? Let the revolution begin at home, with whatever instruments we might come up, so we can play our shambling, broken down song. Everyone’s a different drummer, and the only beat that matters is the one that’s pounding beneath my chest pocket. At least let me fail to get what I might have wanted, instead of having to fail to get what you wanted for me. At least that, dad. Ok?