Questions of Dad

When I catch Istvan Kantor in one of his endlessly posed delivery vehicles, I can’t help wondering about his father. Dear old dad. Is it because Istvan has named and renamed himself, or followed a preoccupation with bloodlines? It’s hard to say exactly, but somehow in his hyperkinetic expressions I can feel some old duet still at play, some family tie opening and closing. I don’t mean to shrink him to a point, or quip him into a Freudian one-liner, but I’d like to take up the lens of the father for a moment in order to see what grows in that place.

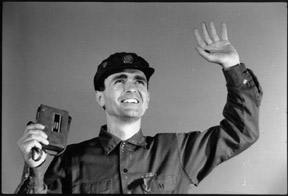

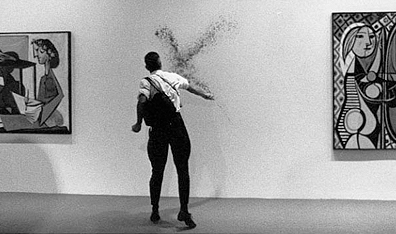

But first let’s shade in some of the background. The hardest worker in un-show business is a one man factory of impromptu performances, machine sex actions, paintings, pop tunes and hyperbolic video knots. Born in Budapest, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 claimed the artist’s roots and attention when he was just seven years old. In the 1970s he studied medicine, and became a folks singer in Budapest’s fledgling underground art scene. There he met mail artist David Zack in 1976 who invited Istvan to move to North America, which he did two years later. He lived for a year in Portland with Zack and Blaster Al Ackerman, immersing himself in mail art and industrial music noise. A year later he left for Montreal where he began performing scores of “Blood Actions,” which has seen the former medical attendant, nurse and para-medic extracting vials of his own blood and painting gallery walls, canvases, street corners. He’s been arrested a time or two for his efforts.

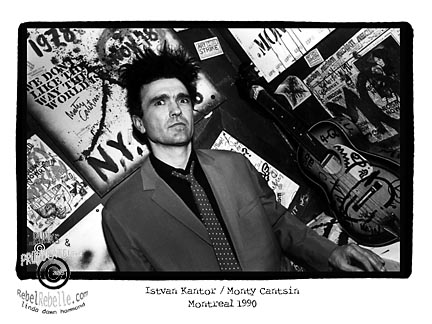

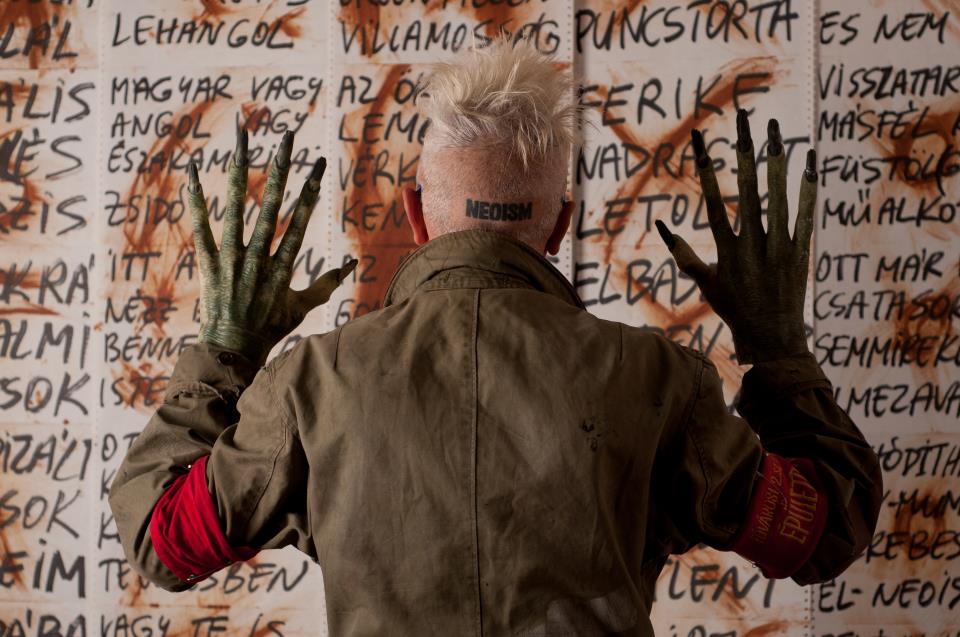

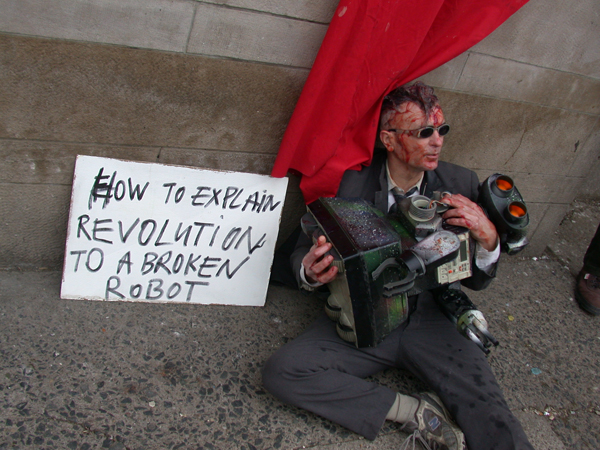

It was in Montreal in 1979 that Kantor became the founder of Neoism, an art movement unquote whose primary embassy was the artist’s apartment, an aperture that issued Situationist-like manifestos with a dizzying, ironic fervour, an anti-consumerism zeal and Rentagon oppositional tactics. He organized a series of apartment festivals and produced scores of actions, incitements and songs, even releasing several records. Following pronouncements of the death of the author, he renamed himself Monty Cantsin and some years later Amen!, and encouraged others to do the same, proliferating viral identities in order to shatter old world ideals of authority, property and the name of the father.

Similarly, his video work regularly features plundered and recirculated material mixed with his own shootings, performance documentations and complexly layered graphics. Office proles and blank generation revolutionaries micro-loop while repeating slogans scrawl across the screen (Remember the Future!), bodies spasmodically jerk and flail in new digital rhythms, the whole ironically declaiming against abstractions of state control and technological determinisms. I want to protest the computer but all I have is a computer to protest with. I want to say no but I am condemned to say it with the only language I can speak. And because his protests remain at a symbolic and abstracted level — he is an artist making pictures of rebellion, instead of, for instance, connecting with and celebrating communities of resistance — he lives in a lonely place. Cut away from a country that used to be home, his landscapes long ago replaced by mediascapes, his revolts are rhetorical instruments of vampire collage, hamfisted propaganda for a state or subjectivities that seem to vanish the closer you get to it.

Istvan works in video, performance, paint, writing and blood; pouring out his manifold expressions at a relentless pace. And who can help but noticing those steely abs, the daily runs along the railroad tracks? Here is an artist that is forever at work, fertile and abundant. The art is emphatic, declarative, pop-toned, as if he’s still shouting through the loudspeakers of his native Budapest, still the child of that failed revolution, waiting to be heard. Each statement is underlined and repeated, each phrase is a slogan, each gesture exaggerated and repeated. Take, for example, his first feature-length outing, Spectacle of Noise (72 minutes 2004), made in his ruined east-end studio in Toronto just weeks before it got demolished by developers. So what does a Governor General award-winning video artist do in his spare time? If you’re Istvan Kantor, there is no spare time. Instead, the seconds are carved up into small, pointed ice picks that hurl themselves into the eyes in waves of serial repetitions. Everything happens again, every overloaded picture longs to overcome the senses, and re-locate its revolutionary imperative back into the body. The instrument of control the movie inveighs against is, ironically, the computer and the surveillance camera, the very military/home technologies that make this vid possible. As the medium turns back to look at itself, the mirror mirrored, it produces a dizzying and hysterical mise-en-abyme, filled with sloganeering intertexts, low rent diaries, and romantic warehouse demons. Can the rhythm of state control also be the rhythm of escape? Caught in the infinite mirror of himself, frame after frame, the artist fashions an elegant and stuttering series of enclosures.

But what about dear old dad? Istvan’s made at least a pair of movies about his father, and I can remember them only distantly. Isn’t there a moment when he sits at a table with the old man drinking a bottle of wine and singing? And then another about a haircut? When I ask him he writes back,

“both of those titles are up on my youtube channel: amenmonty

together with many other videos

titles:

Chanson a mourir

Revolutionary song

these two were also part of my

Nuit Blanche crane-screen installation in 2006

at the Bohemian Embassy lot

and vtape also have a selection

and you can go through several hundred

tapes in my archive if you have a lifetime to waste,

hahaha

istvan”

How could one write about an artist’s work if it would take a lifetime to see it? It recalls the old dream of Joyce writing Finnegan’s Wake, that someone would spend their entire life reading his book. And today’s media artist, or at least, today’s media artist driven by the compulsive urge for exposure and overproduction that marks this digital moment, might pursue this dream from the other side: to create a movie, or a series of movies, that are as long as a lifetime. How could one begin to make a cut, an incision, into that body, in order to begin speaking about it; as if that instant were anything more than a possible trajectory, or the next verse in a tune that never ends?

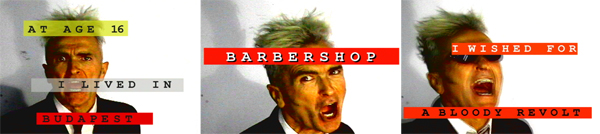

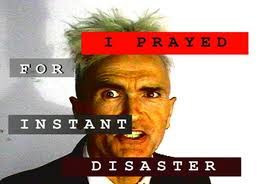

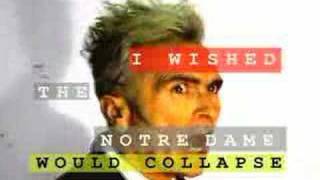

Revolutionary Song (9:15 minutes 2005) is a home-brewed music video. Istvan half-sings, half shouts a memory about meeting up with his father in Paris, a man who left Hungary a decade earlier. And now they would find each other again, in another ancient city of revolution, where his father insists on taking Istvan to a proper barber and cutting off his long hair. Who needs Delilah when you have a father like this? In his re-creation video, the artist, serious and besuited, dances a tango with himself, his whitening hair gelled up in a wave to reveal a cross sketched onto his skull, his familiar red armband in place. The cutting is delirious and insistent, generations of the same image are jammed together in quickly alternating views and run across pictures of glitched revolutionary documentations. Each songline appears in typewriter font against brightly coloured strips laid over the image. And behind his singing a Russian military song rings out via a thunderous choir and a proud military drumbeat. It is the song of a fatherland, and he turns it, strangely and perversely, into a song about his father.

“During the summer I went for a trip

To visit my father in the west

He lived in Paris for almost ten years

I haven’t seen him since he left.

My father took me for a redeeming haircut

He didn’t like my long curly hair

As we drove by some boring monuments

I wished we would never get there.”

Istvan’s wishes lead him to hope for a Paris razed and ruined, its iconic buildings leveled, the revolution taken hold at last, his father dead. But at the same time he offers this curious line: “I wished we would never get there,” as if he wanted to hold onto this moment of delay with his father a little longer. Can’t we linger here a little more, dad? Can we actually sit here, the two of us, in this place between places? And in order for us to breathe in the same car, on the same seat, perhaps some great outpouring of destruction is necessary, perhaps the whole world as I see and know it, would need to change, in order to make that kind of impossible possible. Or put another way, perhaps the artist is asking: how can I hold the place of the failed revolution, the one my father abandoned, in order to conjure another that can only happen now, in the work of the present moment?

If Revolutionary Song shows off the artist as accomplished digital collagist, then his earlier work Chanson a mourir (Song of Death) (6:11 minutes 1988), produces a more traditionally documentary approach to the music clip format. Wearing a workman’s trenchcoat, the artist sits at a table with his mother and father and sings a song while his mother adjusts his coat, and his thin, shirtless father looks on, drinking wine. During the song’s refrain – “Life is shit. Shit shit. Life is filth. Filth, filth. Life is torment.” – dad chimes in with echoing words and paternal assent. Istvan sings about working in a hospital as the bodies roll in, and having to touch their intimate coldness, all this bewildering death somehow become his responsibility.

The artist writes about this video: “I recorded the song “Chanson á mourir” in 1983 with First Aid Brigade, in Montreal, in French, and it was released on my Mass Media album in 1984. I produced this video version in the late 80s, during a summer visit to our family cottage in Surany, Hungary. I translated the lyrics for this occasion to Hungarian, and, accompanied by my mom and dad, I sung it to a backing tape played on a small radio. This was one of those rare occasions when my father agreed to be part of my work. He was always very critical towards my art ambitions and insisted that I become a doctor. Following his wishes I spent several years working in hospitals and studying medical science. This autobio-song tells the true story of my first working day in a hospital at age eighteen, and it commemorates my life as a nurse and paramedic. My mom died of cancer a couple of years later, at age sixty-six, my dad was taken by a stroke in 1997, at age eighty-five. The coat I’m wearing is a vintage workman trench-jacket from the 1960s. My cousin, Gabor Medvigy, cinematographer for most Bela Tarr movies, did the excellent camera work.”

The movie is made in a single shot, without the overlays and meticulously contrived and compulsive interruptions that mark the artist’s later work. Instead, relations between the primal couple and the artist exist in “real time,” and their always shifting vantages — from drinking companion to song partner to bored witness — create a unique in-frame montage. Here in the family everyone has a role to play.

A cantor is a Jewish religious official who leads the congregation in prayer, and most particularly, in song. In Christian churches, a cantor is simply the choir leader. In this videowork the Kantor leads a congregation of his own family back in time, to the first day of his hospital employment, as if he wants to show them the inheritance they had left him with. Why couldn’t you let me be eighteen when I was eighteen? I had barely begun to live before I was dying.

Instead of soldiering on as a doctor Istvan decided to make a name for himself as an artist and singer. And by turning his parents into the assenting chorus (repeat after me dad), he becomes father to his father, head of his own small church, if only for an afternoon. In the short documentary Istvan Kantor: The Neoist (a profile directed by Eric Reid) (7:06 minutes 2011) he says, “I was brought up by the state to become a communist.” Here he names the state as father, a communist country whose well known obsessions with information and control are countered by a singing subject of a Kantor who founds the anti-movement of Neoism by installing himself on a chair in downtown Montreal with a sign reading “Neoism.” Could we call it: the name of the new father? And what is Neoism? The artist insists he doesn’t know. He sat in the chair in order to find out, or at least, to begin a conversation. Not to arrive with the answers, but to become a question. Could this also be a way of holding the father, becoming the father even, not as the one who knows best, but as a place of mutual inquiry? Zen maestro Shunryu Suzuki wrote about “beginner’s mind” though perhaps we could swap out this phrase and insert “Neoist” instead. Here is Suzuki via Kantor: “In the Neoist’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” The father is dead. Long live the Neoists.