Obscured Referents, Approximate Indices, and Counter-Archival Practice

Vtape

February 22, 2008

Curated by Brett Kashmere

There is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory. [1] - Jacques Derrida (1995)

The proliferation of images, image supports, and storage systems in today’s information-based economy requires a radical reconceptualization of the archive. The active insertion of the author could fundamentally transform the archive’s connotative anonymity. This exhibition considers the archive as a site for creative intervention, one that enables new possibilities for preserving and representing individual memory within a larger historical consciousness. In this strange moment of image excess and commercial limitation (due to the increasing privatization of archives by multinational corporations), we are all potential archivists and micro-analysts of our shared social experience. Now is the time to reclaim and reinvent our public memory. The powerful – the government, the mainstream media, the wealthy – have the ability to stamp their own meanings on the past. Equal participation in the constitution and interpretation of the archive is a key to counteracting the unseen hand of authority, and helps to invigorate successful content-sharing applications such as Wikipedia, YouTube, and Creative Commons.

All Samples Cleared!

Anticipating how shifts in technology and privatization would affect media production and access, Sharon Sandusky proposes a new genre: “The Archival Art Film.”[2] This type of film (or video) harnesses elements of the essay, structural, and compilation genres into a hybrid form where the personal, experimental, and historical meet head on and cross-contaminate. Exemplary precursors of this nascent genre include, for Sandusky, Bruce Conner’s Report (1963-67), Michael Wallin’s Decodings (1988), Barbara Hammer’s Sanctus (1990), and Craig Baldwin’s Rocketkitkongokit (1986), among others. In recent years, more and more contemporary artists, from Tacita Dean to Kota Ezawa to Walid Raad, have been playing with/in the archives, opening up dynamic possibilities for counter-archival practice.[3] In this age of draconian copyright law, the archive is rich with subversive potential.

What’s at stake today is who speaks for whom, why, and about what. This is about the authorship of history. However, the uncovering, interpretation, and re-writing of history requires access to evidence that isn’t always legally (read: affordably) available. Transforming file footage, “found” materials, and audiovisual fragments through formal manipulation is one viable and alternative form of sample clearing. “Sampling,” in musical parlance, describes the practice of lifting portions of an existing recording and using this “sample,” usually in a repetitive manner, as a component of a new song. In the process, the original reference often becomes abstracted or obscured. The same strategy can be applied to moving images as well.

Increasingly, videomakers have turned to the techniques of animation as a means to reinvent the image while questioning its representational value. Through experimentation with form -processing, filtering, layering and compositing, degrading and recoding – pre-existing images have become a canvas for greater creative play, a site to begin anew rather than an end in itself. Due to the malleable, recombinant nature of digital media, animation provides an unusually supple instrument for disguise, and, by extension, a means of circumventing the problems of access, ownership, and expense. Drifting between index and fantasy, the animated videos in this program exemplify the idea of original copy, a method of appropriation that involves translation, interpretation and transformation; in other words, quoting without quotation marks.

That Reminds Me of Something

“That Reminds Me of Something” gathers videos that draw from and animate (over) primary sources for illustrative and/or discursive purposes, while simultaneously (almost) erasing their indexical value. Animation, used in this context, raises questions about the truth and reliability of the documentary genre, allowing artists to produce idiosynthetic, anti-authoritarian re-codings of accepted histories. What unites many of these works is a commitment to creatively reveal elisions of history and memory from a subjective position, thereby expanding the possibility of archival-based artmaking outside the margins. Joel Katz makes an important distinction between the terms “archive” (an institution where public records, documents, etc are kept) and “archival” (anything which contains certain attributes of age, status of preservation, and ascribed importance).[4] Not everything that’s archival can be found in an archive, just as certain disruptive or contradictory images are left out of our collective memory bank.

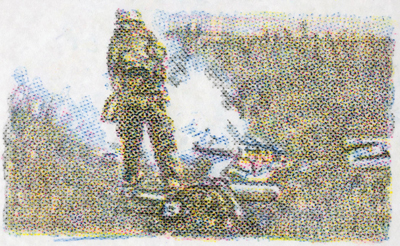

The act of remembrance becomes complicated when events are too distant or too traumatic to visualize. Such is the case with the ongoing Iraq war, which several videos here attend to, whether by re-contextualizing its rhetoric through the selective animation and juxtaposition of media newspeak, or by exposing its gruesome reality. In Stephen Andrews’ Quick and the Dead (2004) a short Internet clip is broken down into component frames and meticulously re-drawn in coloured crayons rubbed over window screening, reproducing the effect of a halftone print. The original footage, which depicts an American soldier nonchalantly stepping over a dead Iraqi man to extinguish burning wreckage, is thereby transformed into a silent meditation on the inhumanity of war. By softening the sharp edge of video, Andrews imbues the fragment with universal resonance and symbolism.

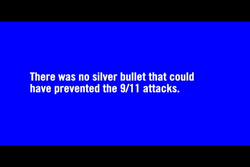

Tony Cokes’ Evil.5: Grin & Bear (No Responsibility Mix) (2006-07) weaves together quotes transcribed from television news and print sources to craft a counter-memory of America’s war on terrorism. Evil.5 uses a single, recurring transition, a left-to-right wipe (indicating a Conservative shift?), to shuttle commentary across the screen. The text begins with a series of passages drawn from Condoleezza Rice’s marathon presentation before the 9/11 Commission, detailing twenty-five years of terrorist hostility towards the United States, much of it now forgotten. Paradoxically, this data was consciously ignored by her administration at the time of the 9/11 attacks. The video then recounts (via Rice) parallels between America’s failure to aggressively pre-empt previous international conflicts, such as World War II, in spite of obvious warnings signs, before cycling through quotations from Donald Rumsfeld, Colin Powell, Richard Clarke, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and George W. Bush about the current war. This text is presented in white atop alternating blue and red frames, a clear allusion to the colours of the U.S. flag.

Like much of his previous work, Cokes’ video tethers animated text to pop music. On the soundtrack, lyrics from a song by Lali Puna (“You’ve been told they didn’t know / You’ve been told their hands are tied”) occasionally correspond to the onscreen text. At other times the relationship between this catchy, up-tempo electro-pop and the grave commentary is less assured. The result is a disquieting, somewhat ambivalent conjunction of seductive aesthetics and clear-eyed political critique. In a similar gesture, Jenny Perlin’s Box Office (2007) juxtaposes two unrelated items from the New York Times. The first, a statement by the U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, compares the current war to the length and experience of watching a movie. The second is a listing of the top grossing films in America. The seeming absurdity of this pairing underlines the Bush administration’s cavalier attitude towards a complex and devastating problem.

In each of the above works, the passive consumption of news cedes to more active viewing, where the spectator must work to create meaning. In the case of Evil.5 and Box Office this requires making connections between ostensibly unrelated components. Drawing from a wider range of sources, Ask the Insects (2005), by Steve Reinke, and Stranger Comes to Town (2007), by Jacqueline Goss, probe the tenuous, unsettled nature of images and identities. During one of the nine “micro-essays” that comprise Ask the Insects, a narrator asserts that “This animation is not an animation but live action footage digitally manipulated… even if we cannot reverse the process and ever get back to the original image we can rest assured that the process did occur and the result is before us.” The result, a posterized, pulsating form, demonstrates the potential animation has for transforming the banal into images of greater beauty and interest, and for illustrating abstract concepts. Moving further in that direction, Stranger Comes to Town is an animated documentary that explores the identity tracking of immigrants and travellers coming into the United States. The video borrows from Google Earth, the online game World of Warcraft, and a US Visit training video traced from the Department of Homeland Security website. Combining interests in science, history, technology and the construction of knowledge, Reinke and Goss generate new forms for the presentation of non-fiction subject matter through whimsy, humour, and revelation.

Although it also culls from the inventory and architecture of video games, How to Escape from Stress Boxes (2006), by the artist collective Paper Rad, is something different. Featuring a flat, pixelled pastiche of cartoon detritus, big-haired Troll dolls, lo-fi graphics, new age iconography, and nearly forgotten advertising slogans (“No Fear,” “Just Do It!”) How to Escape from Stress Boxes is replete with superfluous elements not fit for a formal repository. Anarchivists of the recent past, Paper Rad present a dark reflection on digital age alienation and media overload. As Paper Rad member Jacob Ciocci writes, “In the ’70s and ’80s cartoons and consumer electronics were bigger and trashier than ever and freaked kids out… Now these kids are getting older and are freaking everybody else out by using this same throw-away trash.”[5]

Towards an Ecology of Images

Ciocci’s comment and Paper Rad’s video illustrate that images have become increasingly disposable in today’s meta-media environment. Conversely, we’re living in an era of increased environmental awareness and responsibility. Global warming, greenhouse gases, carbon footprints: these are the daily headliners. So why do we still produce and consume images at an earth shattering pace?

I propose we generate a renewable, and therefore, more sustainable image ecology, by re-investing older material with critical, new meanings, just as found footage films by Guy Debord, Arthur Lipsett, Chick Strand, and Craig Baldwin did decades earlier. Eschewing the manufacture of cultural products and passive social relations that define capitalist ideology, the artists in this program raise important questions in the context of media saturation and its corollary—media impoverishment. Today apolitical samplers like sound and installation artists Christian Marclay and Douglas Gordon, as well as political essayists such as Michael Moore, utilize found record covers, Hollywood cinema, and archival footage to achieve marketable signature styles.

More significantly, as the means of détournement become co-opted by the cool scouts of mass media, so does the possibility of critique and of subversive actions take on greater urgency. The artists in this program work with found materials to articulate an ethic through creative appropriation. Unlike Richard Prince’s epic, re-photographed prints of the Marlboro man, these détourned “archival art” videos aren’t produced for the marketplace; rather, they seek to dismantle the politics of truth by revealing obscured aspects of reality, like the hidden consequences of war.

Notes

1. Jacques Derrida, Mal d’Archive: Une impression freudienne (Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1995); trans. Eric Prenowitz, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996). 2. Sharon Sandusky, “The Archeology of Redemption: Toward Archival Film,” Millennium Film Journal 26 (1993): 3-25. 3. In response to this situation, a plethora of international conferences, symposia and exhibitions have recently been staged. See, for example, Taking a Stand: A Conference on Activism in Canadian Cultural Archives, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, June 15-16 2007; Open Archive #1: Trajectories in Audio-Visual Culture, Argos Centre for Art & Media, Brussels, October 2-November 10, 2007; Who Makes and Owns Your Work, a multipart event on sharing, distribution, and intellectual property, Stockholm, November 2007. 4. Joel Katz, “From Archive to Archiveology,” Cinematograph 4 (1991): 97. 5. Jacob Ciocci, cited in “Paper Rad: Biography,” Electronic Arts Intermix website, http://www.eai.org/eai/biography.jsp?artistID=7440