Notes on a talk by Michael Stone at Centre of Gravity, March 11, 2013

Thoughts

How do you work with your thoughts in sitting meditation? Whenever you experience sensations, urges, thoughts or fantasies, it can feel like they are happening to a you. Why? Well, all day people keep talking to the you, referring to the you, pointing to the you. It makes it feel like your life is happening to the you. As if the outside world has been arranged so that you can experience it. As if this stoplight is your stoplight. As if the person in front of you in line, is standing in front of you, the most important person in the world. They only built this health food store so that you could walk into it. This dangerous delusion, the root of so much suffering, is fairly commonplace.

The cushion is a really great place to work with this feeling that the entire world has been arranged so that you can experience it. Another way of saying this is: it’s a great place to work with self-consciousness. Sometimes embarrassment arises, for instance, and it feels like it’s happening to a me. That’s my embarrassment. Or if you’re filled with sitting envy, or if busyness occurs, it can feel like “I’m so busy” or “I’m so envious.” Sometimes people who really get into mindfulness practice as pure technique, who become greatly concentrated, can become very self-conscious. When you become mindful you can really start to feel every sensation, some days it’s hard to step onto the streetcar because there are so many sensations.

Mindfulness

There is a distinction between mindfulness and self-consciousness. Self-consciousness is a space where everything you’re experiencing is related back to yourself. Mindfulness practice is where we experience events in a more phenomenal way. We experience energies, surges, intensities, but we don’t identify with them. Whoa. That’s pretty hard not to do.

If I’m “doing” meditation, I’m still part of a doing world. I’m not unwinding. I don’t have spaciousness. How can I unwind?

Shelter

There was a person riding the subway late at night who noticed a young boy carrying a large suitcase. Eventually the boy wheeled the case over and asked if he knew where the shelter was? “No, but here’s $10. You could take a cab and they’ll show you.” Later, the rider berated himself. Why didn’t he do more? Help him, take him there himself, he had time. This went on for a number of days of delicious self-flagellation until this realization: this boy was suffering. And he was also suffering. He touched the experience of just suffering, he saw suffering itself, and how it flowed through both the boy and himself.

When we’re in the place of strong emotions can we feel them in a generous way, in the space of mindfulness, not self-consciousness? All the thoughts that move through your mind don’t have to be claimed as your thoughts. When you’re sitting in daily practice try to make a distinction between the open spaciousness of mindfulness and self-consciousness. How to practice so that the self, the me, myself and mine, is not the magnet that everything is adhering to?

How can we work with not personalizing emotions? How to feel them as energies? Clusters of sensations, old and new patterns? There is a line, always shifting, between opening and closing, how to find the right distance? When is it appropriate to take distance from strong emotions, and when should we let them overtake us so that there’s nothing left of us?

Edit

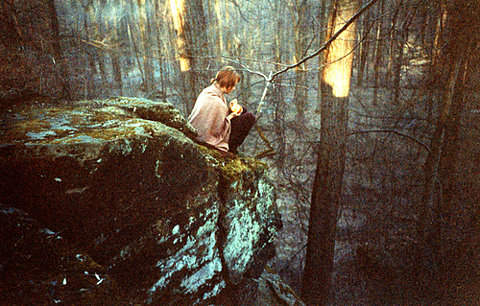

As a movie editor, working again and again with the same clips, trying to find their optimal arrangement, I need to be close enough to let the pictures touch me. To be moved. And then I have to back off, and take distance, so that I can see them as if for the first time. And then I need to get close again. This movement of near and far, of touching and seeing, is the dharma gesture of editing, is the way one might work with strong emotions. It’s what Freud called fort und da, near and far, as a child tries to negotiate his absent mother.

Self-consciousness allows us to orient ourselves, and once we’ve checked that compass we can drop it. Then there’s more fluidity. Self-consciousness is like a block of ice. There’s a famous saying by Shunryu Suzuki: “A big block of ice makes a lot of water.” That’s the answer I should give to every question. Meditation is like a hair dryer. Mindfulness is actually a hack, it hacks into self-consciousness.

Practice

Michael’s translation of Shantideva’s text, chapter 5, selected verses

41

Some students have a practice that is geared towards concentration

If that’s your practice you should extend it through everything you do

And explore long periods of time where you don’t let your mind wander.

Sometimes you should reflect and ask yourself, “How is my mind behaving?”

And you should look even more closely at your mind.

42

However, if you’re not able to stay concentrated

Or if this isn’t the focus of your practice (due to your character)

If you find yourself afraid

Or if you find yourself over-excited in celebration

You should relax. Just relax.

It’s taught that at certain times, when you are giving yourself completely,

You need not worry about following ethical guidelines.

Giving yourself totally is the perfection of ethics.

43

When you intend to do something

Give yourself fully and follow through with it

If you apply yourself, you are practicing.

48

If there is strong craving or anger in my body and mind

If I’m clinging

At that moment I shouldn’t do anything or say anything

I should just be awake and still

like a tree.

49

If my thoughts are distracted, if I find myself talking too much

If I’m feeling self-important or much too small,

If I am only seeing the faults of others

Or other peoples’ pretensions, or my own,

Of if I have fantasies of deceiving others,

Or if I am eager for praise,

Or if I blame another,

Again I should stop and be awake and still

like a tree.

If I crave material wealth, honour or notoriety

Or if my desire for friends comes from feeling inadequate

I should be still and awake

like a tree.

58

My mind should be like a mountain.

63

If I split open my bones

And look right into the marrow

And I ask myself:

What is the essence of “me”?

I’ll likely stop guarding myself so much.

70

I should conceive my body as a boat

A mere support for coming and going

A vehicle for ferrying others,

And in thinking of my life as a ferry

I transform it into a wish-fulfilling jewel.

71

I should smile

I should be a friend and counsel in the world

I should frown less.

72

I should take delight in moving chairs around and opening doors

74

I should be a student of everyone.

I can learn from anybody.

If someone does good or says something new and clear

I should say, “Well said.”

76

If someone speaks of my good qualities

I should take this in and be aware that I have

Good qualities.

Then,

The deeds of others will be obvious.

If I care for my own heart

I’ll see the good in others.

79

I should speak from my heart

and only about what’s relevant.

80

When I meet someone I will say to myself

I am going to use this moment to awaken.

Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (from Healing Anger): “Bringing about transformation in one’s outlook and way of thinking is not a simple matter. It requires the application of so many different factors from different directions. For instance, according to Buddhist practices, we emphasize the unification of method (or skillfull means) and wisdom. So you should not have the notion that there is just one secret, and if you can get that right, then everything will be okay. One should not have that kind of notion.

For example, in my own case, if I compare my usual mental attitude today, my mental attitude in this situation, to that of 20 or 30 years ago, there is a big difference. But these differences came about step by step. Although I started learning Buddhism at the age of 5 or 6 years, at that time I had no interest in it, although I was seen as the highest incarnation. Then-I think about 16 years old- I really began to feel serious and really tried to start serious practice. Then, in my 20s, even when I was in China and there were a lot of difficulties, still, whenever I had the occasion, I received teaching from my tutor. Then, unlike the previous time, I really made an effort from within. Then-I think around the age of 34 or 35-I really just started to think about shunyata, emptiness. And as a result of intensive meditation based on serious effort, my understanding of the nature of cessation became something real. Then, I could feel some sense: “Yes, there is something, there is a possibility.” That really gave me great inspiration. Still, at that time, bodhicitta was very difficult. I admire Bodhicitta, that kind of mind is really marvelous. But the practice was still very far away in my 30s. Then, somehow in my 40s, mainly as a result of studying and practicing Shantideva’s text and some other books, eventually I came to have some experience of bodhicitta. Still, my mind is in bad shape. But somehow, now I have the conviction that if I had enough time, appropriate time and an appropriate area, I could develop bodhicitta. This has been 40 years.

So, when I meet people who claim to have attained high realizations within a short period of time, sometimes it makes me laugh, although I try to hide that feeling. But you see, deep down, mental development takes time. If someone says, “Oh, through hardship, through many years, then something will change,” then I see something is working. If someone says, “Oh, within a short period, two years, something big changed,” that is unrealistic.”

Hard Work

All of the chapters in Shantideva’s book are leading up to the penultimate chapter (8), the most famous chapter, which is about meditation. Only it’s not meditation as we know it. According to Shantideva, meditation is about exchanging your body for someone else’s. This is how to get bodhicitta flowing. You understand that others are yourself. You are others. We need to develop the insight that when I think of my own advantage, it leads to problems for myself. An old habit. But if I can think of what I am at the deepest, I’m not as limited as I think I am. Being in your narrow sense of self is a disadvantage because you can’t have bodhicitta, you don’t have the passion to be awake. Or the passion to be in a conflict where your simple presence de-escalates because you are bringing, you are being, non-violence.

This is one of the few Mahayana texts written in the first person. You get a sense of someone saying to monastics: don’t forget about relationship as a vehicle for awakening. This is what he calls practice. We’re all bound up with one another. Enlightenment and practice is hard work, gradual and messy.

Erin

Yesterday I went out for a walk with my friend Erin in Vancouver. Erin has a love/hate relationship with the city, she’s even made a list of things she can’t stand: certain buildings and streets. She’s going to take samples of each of these things and put them in alcohol and create tinctures. Whenever she feels down about the city she’ll just take the tincture. Maybe we can all do this with someone we don’t like. It’s easy to find people who are good – you’re lucky if you find an awful person to help you practice. If you get a good swab you can make a tincture with them, and it will be easy because if they’re really difficult, they’ll stick to you.

Dancing the World into Being: A Conversation with Idle No More’s Leanne Simpson

(from Yes Magazine, March 2013)

Naomi Klein speaks with writer, spoken-word artist, and indigenous academic Leanne Betasamosake Simpson about “extractivism,” why it’s important to talk about memories of the land, and what’s next for Idle No More.

Naomi: I think a lot of it has to do with the state the land is in. Because in B.C., that was the outrage over the Northern Gateway routing—“You want to build a pipeline through that part of B.C.? Are you nuts?” It was almost a gift to movement-building because they weren’t talking about building it through urban areas, they were talking about building it through some of the most pristine wilderness in the province. But we have such a harder job here, because there needs to be a process not just of protecting the land, but as you were saying, of finding the land in order to protect it. Whereas in B.C., it’s just so damn pretty.

Leanne: I think for me, it’s always been a struggle because I’ve always wanted to live in B.C. or the north, because the land is pristine. It’s easier emotionally for me. But I’ve chosen to live in my territory and I’ve chosen to be a witness of this. And I think that’s where, in the politics of indigenous women, and traditional indigenous politics, it is a politics based on love. That was the difference with Idle No More because there were so many women that were standing up. Because of colonialism, we were excluded for a long time from that Indian Act chief and council governing system. Women initially were not allowed to run for office, and it’s still a bastion of patriarchy. But that in some ways is a gift because all of our organizing around governance and politics and this continuous rebirth has been outside of that system and been based on that politics of love.

So when I think of the land as my mother or if I think of it as a familial relationship, I don’t hate my mother because she’s sick, or because she’s been abused. I don’t stop visiting her because she’s been in an abusive relationship and she has scars and bruises. If anything, you need to intensify that relationship because it’s a relationship of nurturing and caring. And so I think in my own territory I try to have that intimate relationship, that relationship of love—even though I can see the damage—to try to see that there is still beauty there. There’s still a lot of beauty in Lake Ontario. It’s one of those threatened lakes and it’s dying and no one wants to eat the fish. But there is a lot of beauty still in that lake. There is a lot of love still in that lake. And I think that Mother Earth as my first mother. Mothers have a tremendous amount of resilience. They have a tremendous amount of healing power. But I think this idea that you abandon it when something has been damaged is something we can’t afford to do in Southern Ontario.

Naomi: Exactly. But it’s such a different political project, right? Because the first stage is establishing that there’s something left to love. My husband talks about how growing up beside a lake you can’t swim in shapes your relationship with nature. You think nature is somewhere else. I think a lot of people don’t believe this part of the world is worth saving because they think it’s already destroyed, so you may as well abuse it some more. There aren’t enough people who are articulating what it means to build an authentic relationship with non-pristine nature. And it’s a different kind of environmental voice that can speak to the wounded, as opposed to just the perfect and pretty.

Leanne: If you can’t swim in it, canoe across it. Find a way to connect to it. When the lake is too ruined to swim or to eat from it, then that’s where the healing ceremonies come in, because you can still do ceremonies with it. In Peterborough, I wrote a spoken word piece around salmon in which I imagined myself as being the first salmon back into Lake Ontario and coming back to our territory. The lift-locks were gone. And I learned the route that the salmon would have gone in our language. And so that was one of the ways I was trying to connect my community back to that story and back to that river system, through this performance. People did get more interested in the salmon. The kids did get more interested because they were part of the dance work.

No Future

Capitalism doesn’t believe in its own future, so it says let’s gamble it all right now. I’m going to extract whatever I can right now. From a Buddhist perspective this is stealing – stealing from the future and calling it growth. This is the mind of extractivism. The I is the extractivist. It takes whatever it can get. Generosity is the displacement of the me. It’s the opposite of bodhicitta, of love. We have to love all the places in Vancouver we don’t like. We have to find a way to hold non-pristine nature, and that includes you. You’re not pristine nature. You have this thing called baggage, and that baggage needs to be held, to be loved. We have to intensify our relationships.